Education is the handmaid of society and is consecrated to the betterment of mankind. I have conceived the occasion of this Commencement to be an opportunity for brief analysis of the problem which is man's today, the problem of education,—how to be intelligent. And since the highest intelligence implies goodness, consideration of how to be intelligent might also be characterized as the problem of the church as well as that of the university.

Is man to be the master of the civilization which he has created or is he its victim?

Thus I would phrase the all-important question, to which the multitude of other problems of the time are but subordinate details, and with which education must concern itself, primarily and without delay. Has man in his individual capacity explored the realms of science and appropriated knowledge of the potentialities of these beyond his capacity to control the forces he has released or combined?

Or again, collectively, has man in his organization of society created a structure, as massive as that which we know, without offsetting the weaknesses of its flaws, so that subjected to strain, even comparatively slight, the gross ponderousness may crumple the imperfect part and topple the whole into tragic and lasting ruin?

From the remote beginnings of human history, when man stepped out from the background of the ages to take his place as the dommant.farm of ie he has progressed securely because of the fact that agencies of malevolent group could not be assembled with such speed nor to such extent against more peaceful assemblies of men as to be of more than local consequence, as well as because of limitation upon the extent to which destructive forces were available. Malignant diseases epidemic to alarming proportions, nevertheless could prevail only within restricted zones Social anarchies were but of provincial consequence in the last reanalysis. For long eras, meanwhile, social changes of such advantage as to commend themselves and to maintain themselves under the necessities of transmission from one people to another, could carry with them their credentails of advantage in practical operation, by the time that they succeeded in piercing the insulinsulation that among men separated group from group.

Wars previous to the World War, even those most extensive and most bitterly fought, created physical destruction, economic chaos and moral disintegration of only minor consequence, from the viewpoint of the world as a whole. for all was so quickly and thoroughly correctable, through drawing on the great reservoir of the areas of peace and quiet and through utilization of the latent resources of the great territories of the earth that had been unaffected and unharmed.

Moreover, wars were in the main but tournaments on heroic scale, of armed knights in professional contacts, and battles were largely the crash of mailed fists, striking with resounding clang, one upon the other, yet usually affecting but to small degree the respective bodies as a whole.

In the World War, on the contrary, even more definitely than were the governments of the world drawn into the maelstrom of conflict, the resources of the world were drawn into the vortex of economic deficit. The ultimate decision was only in part the decision resulting from the conflicts of armed forces. The winning of victory awaited the straining effort of shop and mill and mine and farm. The minds and souls of entire populations were conscripted to support the lines of combat, and none there were who were unaffected. And now, in proportionate degree, as compared with the wars of the past, the reaction from this great war brings moral inertia and social indifference which reaches alike the remotest hamlets of this great country and those of distant lands.

In short, the conditions of life in peace or war have suddenly changed to an extent that neutralizes many of the accepted axioms of the past and reduces the common denominators of that-which-is-to-be with that-which-has-been to an extent unknown before.

Under such circumstances, swung far from its moorings, caught and carried by unknown currents, and buffeted by threatening waves, civilization tosses in a sea of physical and social forces without lightening of cargo or concerted demand that the portents of the heavens shall be observed to seek direction wherein lies safety for mankind!

The times are not infrequently spoken of as to a new Rennaissance but the analogy has little of exactness. In the Middle Ages the process of education had largely disappeared and the material of education had been almost completely lost. The subject matter for human study were the newly discovered literatures and records of the past, liberated and made accessible to mankind by the newly devised art of printing. The acme of ambition was to know as much as men before had known. The look was backward and not forward. The scrutiny was of imperfect symbols of facts and not of the facts themselves. The goal of man through education was to become enabled to set himself apart from men, and the affairs of earth, in search of a restricted heaven. The theory was one of exclusiveness rather than one of inclusiveness. Learning was conceived to be a badge of aristocracy whose lustre would be dimmed by contact with the crowd.

In the new era, upon which we are embarked the technique of education has been developed to high degree and the content of available knowledge has increased to an extent beyond possibility of mastery of more than a minute proportion of it by the individual, however extraordinary his mental capacity. The scholar of greatest intellectual acumen can scarcely claim command of his chosen subject. And beyond this, the subject matter of the new learning must be largely the intangible and infinitely more difficult problems which have to do with the future instead of exclusively with those of the past. The look must be forward and the premises of the conclusions must be founded on realities rather than on symbols of these. The effectiveness of education must be judged on the basis of its influence among men. The theory must be one of the greatest possible inclusiveness of mankind within the realm of influence wherein the mind holds sway. Learning must become flesh and dwell among men. Its garb must first be the gowns of men, even if later it is conceivably to become the livery of heaven, and finally, its method must more nearly approach the method of prophecy than that of history alone.

This argument is not based upon subtle reasoning nor upon involved logic. The data bearing upon it is available to all and is as simple as it is available. The analysis and synthesis by science of the forces of nature have reduced the size of the earth, on which we dwell, to a microscopic fraction of that size which formerly pertained to it and have crowded into this reduced area populations, largely increased over that of former times. Distance is not a matter of miles, but rather of time, a matter of how long it takes to go from one place to another, or how long it takes to have communication from, place to place. With the successive developments of transportation and intercommunication there has been coincident and proportionate decrease in the distances by which men and peoples are separated one from another, with consequent result that in effect now all men of the earth brush elbows, one with another!

The time of a journey a century and a half ago from this historic university to the colonial college whence I have come would now Suffice for a trip from Philadelphia to Central Europe,—and hundreds take the journeys of the latter length where one would formerly have gone the shorter distance.

I have recently seen the life insurance policy issued to Daniel Webster in 1844, and even then the world was so much too large for inclusion within any one man's sphere of activity that Mr. Webster's insurance was payable only if he did not journey abroad, or north of the forty-eighth degree of latitude, or west of the Mississippi, or south of the southern boundaries of Kentucky or Virginia.

The newspaper delivered to you every morning gives greater wealth of information each day than any man could have acquired in a year by all the, mediums' of information available when our government was established. The philosophical speculations of your dinner companions are based upon data gathered from the ends of the earth and your response is the result of another accretion of knowledge of like range. We have more direct and quicker access to the affairs of the world than our forefathers had to the affairs of neighboring colonies. The crowding of the hosts of the world into this winch amounts to a diminutive area, as compared with former times, makes the permutations and combinations of life, originally measurable and understandable, now approach infinity and unsolvability.

This all means not only a greater community of interest among the peoples of the earth, in which what one does is immediately known to all and is of consequence for good or ill to all. Essentially it means also a faster evolving life, through which the present crowds in upon the future, with a result that we of the present are in effect submerged within the future as a water-craft of speed is immersed beneath the wash of waters with which its prow is but just in contact. One can afford to be philosophical about the projecting rock which he leisurely approaches by poling a raft but the menace of the same obstruction to a hydroplane, cleaving the waters, demands quick and intelligent action.

We do not yet know what is to be the effect on the human mind of continuous impact of the influences of vastly enlarged scope and high intensity, and the consequent necessity to the mind of absorbing a variety and a gross content of knowledge, the like of which has been unknown in times before.

From consideration of these among many current phenomena, I repeat: Is man the master of the forces of the civilization which he has created? Or is he their subject? Are the magnitude and the intensity and the speed of life today within man's control, or is he a helpless passenger in a world run wild ?

The answer lies, I believe, in the extent to which man has disposition to develop his mental powers and to increase his intellectual capacity to understand the problem, and in the extent to which he can make his will operative, and with what speed!

The individual human being, independent of his fellows, and the self-sufficient, self-contained community, alike are relics of times gone by. Ihe complicated mutual interdependence of man upon man in the high specialization of individual vocation and interest in the urban population, as compared with the rural, has its analogy in many of the distinctions between the attributes of the present and the past.

This is the significance of the statement that life has become inclusive rather than exclusive, and that recognition of and acceptance of this fact must precede all else, when we undertake to devise a method of escape from the dangers which threaten mankind. An interlocked society, in which the stumbling step of an individual invariably induces a stagger in the march of the group, largely eliminates necessity for considering theoretical arguments concerning the merits of oligarchies, castes, or classes, and insists that no matter is of more practical concern than that what can't be got rid of shall be absorbed. The same spirit of ruthless logic which conceivably might have justified the demand for subjection of the many to the will of the few, in the times of the Medici, in these times precludes the possibility of this and makes insistent an immediate commitment to a policy, diametrically the reverse.

Yet even this statement requires further elaboration, because it is necessary to consider whether we have not gone beyond the stage where the omnipotence, if not sufficiency, of majority rule can be conceded, in the sense in which we have so long accepted it. May not, indeed, the truth-seeking and courageous spirit of inquiry which must prevail, if man is to escape destruction or chaos, discover that as formerly special privilege could not be held within the few, so now it cannot be held within a restricted group of more ample proportions, even when that group has become the many. In other words, can the rights of special privilege to which minorities are denied, be confined and held even within majorities, since unprecedented offensive power has become accessible to minorities, through acquisition of the forces of nature and through the complications and consequent weaknesses of our social organization.

A shuffling horse, a ramshackle covered wagon and what is probably a psychopathic driver, supplemented by a product of modern science threaten the financial center of the world, in a disaster which with all its tragedy accomplished but little of the destruction which was almost inevitable from sue an attempt!

is not an agreeable subject for speculation, but if evil cannot be influenced and if minorities cannot be absorbed, what is to be the end? Is this too general? Then let us be specific! Deadly gasses which give the individual man capacity to destroy whole populations, availability of cultures 01 disease an knowledge of the possibilities of propagation of these; genius for mechanica devices by which the culmination of the destructive forces of shattering explosives can be delayed and timed at desired place for maximum effect such are he resources for the Sampson, blinded mentally and spiritually, who would make the pillars built for the support of civilization become its destruction

But of still greater seriousness is the effect upon progress of the hightyexplosive, destructive idea which by our inventions and our organization of society can be instantly utilized to maximum influence by all the forces ignoral malevolence, or of mental disease. As in the towering forest the commands mands of utility impel conquering man, in his onward sweep, to discard the branching tops to dry and wither until in their death the live timber is threatened, so in the world of men. The wastage of civilization, cast aside and forsaken, becomes the inflammable tinder of sicontent into which thrown, whether carelessly or by malice, the smouldering fire of resentful thought, there spring of mania for destruction. The feed upon the abandoned realms of waster and gain strength therein until at last power and will is theirs to atattack the forces in civilization which men call good.

Such are some of the phases of problems of our time. Are considerations sush as these to be allowed to make for pessimism and cynicism? As frankenstein fabricated his monster, and later through abandonment and fear lost his control over it, has civilization breathed life into inanimate force only to run in terror from its threat? The answer is surely "No." unless the spirit of education is dead and civilization has lost its courage! It is never to be forgotten that the condition arises because of the perversion of forces which have been originally devised and arranged for the benefit of man, and that these forces are still available for that end, if rightly applied. The situation offers to men of our time the supreme challenge of all history, and opportunity in dimensions such as no other age has ever known.

Disease there is, nevertheless, and it is in the minds of men and is inaccessible therefore to familiar and traditional methods of correction. The legislative hall, the courtroom and the prison are alike powerless in this realm. We cannot make men good by legislation, nor make them work by injunction, nor can we discover malign intentions by the threat of punishment. Only by such rehabilitation of the mind of man and such increase of the areas of intelligence and goodness in the thinking of mankind as shall eliminate the chance of infection by the powers of evil can the opportunities of life be insured to these who crave its major satisfactions. The new sources of power for unrestrained minorities are bound to transform our conceptions of what is expedient, if not what is just, and to insist upon the incorporation of the interests of minorities as never before, within the province of the world's concern.

In 1837 Horace Mann, accepting appointment to direct the work of education in Massachusetts, based his decision on the thesis that he believed in the accelerative improvability of the race. Today, as we go forth to meet the world's challenge and to grasp its opportunity, we must assume that the boundaries of men's intellectual capacity are far more distant frontiers than have yet been reached and that the power of man's soul has been but little realized.

At the same time, it is not to be forgotten that intellectual capacity, ungoverned by the soul, may sharpen the knife of the knave as well as give edge to the axe of the pioneer, or in more modern terms, construct more deadly munitions as well as devise more beautiful dyes

We have not done well in our institutions of higher learning so largely to forget the religious impulses which led to our foundations and so completely to shrink from responsibility for the soul's nourishment while we have so zealously tried to feed the intellect. Yet for our purposes today we need not discuss these functions separately, for the best education must accept the principles of the best religion, and the inspiration of both is "Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free."

It is imposed upon us in this connection not to underestimate the difficulties nor the temptations which beset the quest for truth. We need to remember constantly that we are trustees of the rich endowments of truth which have been gathered through ages past and handed down to us for transmission to the future.

Unfortunately for the eveness of progress, the well-intentioned thought of the world tends to split into two conflicting camps, the reactionary wing of which assumes that approximate truth has been achieved and that even consideration of any modification is undesirable, while the radical wing tends to condemnation of all that we have inherited from the past and to assumption of disproportionate advantage in the new, as compared with the old. The genuine seeker for truth cannot afford to forget in this controversy that the argument for the new can be made' far more attractive and forceful than the eventual facts will vindicate, because the errors of the known are always so much greater than are the weaknesses which can be proven in that which has not been tried.

Furthermore, making all due allowance for the aggressiveness necessary for those who in attacking fallacies of the existent order would avoid futility, it still remains a fact that liberal thought suffers and is handicapped in accomplishment by the bigotry of liberals, men who in revolt against the intolerance of conservatism swing to position of the other extreme, and there implant themselves with an intolerance as great as that of the group against which they strive.

Abstract truth perhaps can never be completely known. The spirit of truth, however, is a constant which recognizes that the formula of truth, while never a static thing, is something which is calculated on the basis of known factors and the interrelations of these, and that deductions from and utilization o these are essential, if we are to hope for greater usefulness in corrected formulae. Meanwhile, in our search for greater value, we have to be on our guard not only against these things which would detract from the benefit which our corrected formulae will confer but also against those things which would detrac from the accuracy with which they might be applied.

There are, among others, several great influences today which hamper that accentuated spirit of truth which Allen Upward in "The New Word called "Verihood," in which is included the whole import of the phrase the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth." These influences can be largely included in a threefold classification.

a. Insufficiency of mentality, or over-professionahzation of point of view.

b. Inertia of mentality or closed mindedness.

c. False emphasis of mentality or propaganda.

Concerning over-professionalization, I am coming to wonder more and more about the whole problem of world organization. What is it that we are trying to accomplish? And for what does all the intricacy of organization exist Certainly not for its own self-perpetuation. But do we always remember that these siller spheres of specked interest have been created for the quicker and more effectual rounding out of the great unit of life as a whole What that we are trying to do? What is the point of our code and the technique of our particular activity m life? To what does the treme specialization in intellectual effort no less than m industry pomt. is the object of constantly increasing the speed with which we vibrate within our given orbits?

Just as long as men look at the things they do, as ends in themselves, they will lack the perspective which will make the work they do most vital in the long run to the world's affairs. We all know lawyers who are more interested in the intricacies of the law than in securing justice. There are doctors, perhaps, who see in preventive medicine a danger to their practice. And the minister is not half rare enough who is more interested in the complicated questions of theology than he is in carrying conviction in regard to the living God. And in the business world the great indictment has been that its men have been more interested personally in acquisitiveness than in adding to the economic wealth of the world.

For illustration, let us be self-analytical for a moment. If the university puts itself into a position where it is more interested in producing education pleasing to itself than in furnishing an education which will be of service to the world at large, the university is foregoing its great virtue. It is losing all that it is putting in, except in so far as it gets out of it satisfaction for itself. This, in the last consideration is an entirely insufficient virtue, a disproportionate return for all that has been contributed during the years of the past, an unpersuasive justification for the appeals we are making to the world, not only to tolerate us, but to add to our resources that we may continue our work.

In regard to mental inertia, the favorite figure of the philosophers for all times with respect to close-mindedness has been blindness. One of the most suggestive poems in our language is Zangwill's poem, "Blind Children" in which he pictures the joys of a group of children who having been always blind have suddenly their sight restored and their eyes opened to the beauties of life all about them. William James wrote one of his greatest essays on "A Certain Blindness in Human Beings." But the particular figure in regard to blindness which seems to me perhaps most important of all is the statement of Seneca in regard to his wife's fool who was blind, in which Seneca said that the tragedy of the girl's blindness was not that she was blind, but the consequence that because of her blindness she thought all the world was black. This is the evil of close-mindedness, that men ascribe to all things outside the range of their interests the same qualities with which they view those things within with which their relationship tends to be a selfish one and thus they become incapable of understanding that which is without the range of the limited vision which is theirs. Too often thus they become subject to the great condemnation of which Swedenborg spoke when he said that the great curse of those who knew the truth and did it not was that they lost the ability to know the truth,—a bit of philisophy which it is needful for most of us to carry over into the spheres of our especial thinking and our especial activities.

And as for false emphasis, the spirit of propaganda has never, of course, been absent from the world. Yet the explanation of its prevalence at the present time seems to me to lie largely in the artificiality and extraneousness of the habit of war and its customs, recently imposed of necessity upon every detail of human life.

However unsavory the odor of the reflection now, apart from the exigencies of the struggle, the fact remains that breeding of morale of the people for war involved, in the censorship, the suppression of truth as well as falsehood; and in the policy of propaganda involved the enthronement of part truths and emotional appeals above complete truth and the dictates of reason. But now that war is passed the spirit of propaganda still remains in the reluctance with which there is returned to an impatient people the ancient right of access to knowing of the truth, the right of tree assembly and the right of freedom of speech. Meanwhile, the hesitancy with which these are returned breedsin large groups vague suspicion and acrimonious distrust of that which is published as truth, and which actually is true, so that on all sides we hear the query whether we are being the facts. Thus we impair the validity of the truth and open the door and for authority which is no, justly theirs to he ascribed to falsehood and deceit.

If space permitted, I should like further to speak in regard to the qualities of leadership, which the times demand, as well as something of the obligation which devolves upon education to train for leadership. desired that it should not be said of American education, as Stevenson made one of his characters say of English education in former days,"By he defects of ruler of an empire."

I would not have universities incapable of educating for Potions of highest responsibility, but I would have them recognze that raising the intellecttual l evel of the maś oƒers the opportunity for the man of genius to emerge, and, if the resources of knowledge are available, as surely produces leadership as would be done, if all opportunity were offered to the tew, to exclusion of the many.

Also I would emphasize certain principles of leadership such as that through the ages the cumulative tendency has been for power to flow from the few tp the many, and that authority in these days is derived from qualities that make for influence rather than from attempted domination.

Likewise I would argue that leadership is tested by the extent of its ability to produce and utilize leadership in others, and that its value is reckoned in terms of service to other, rather than in terms of ascendency over others.

Compare the possible effects on humanity of these two types of leadership. Macaulay says of Frederick the Great,

"In order that he might rob a neighbor whom he had promised to defend, black men fought on the coast of Coromandel, and red men scalped each other by the Great Lakes of North America."

Opposed to this, consider the teaching of Christ, "Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me."

In conclusion, shall we not say that the hope of civilization is based upon the unprovability of man, and the consequently enlarged intellectual capacity and intellectual accomplishment of the race?

You who go out today as graduates of this great university, notable among institutions of higher learning, are beneficiaries of special privilege in its most legitimate form, and are subject in particular degree to the laws of noblesseoblige. To such as you the world looks for its redemption because of your increased equipment and your intensified willingness to accept responsibility. No more romantic field ever awaited man than lies before your eyes. Through you and such as you, it is given that learning and goodness and beauty shall conquer and live! As knights to tourney you go forth, under the shining plume of truth and when your course is run and when your quest is ended, may the proud words be yours, which were the boast of Cyrano de Bergerac:

"Tonight, when I enter God's house, in saluting, broadly will I sweep the azure threshold with what, despite of all, I carry forth unblemished and unbent,—my plume!"

Address by ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS at the Commencement Exercises of theUniversity Of Pennsylvania, JUNE 15, 1921

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1921

August 1921 -

Article

ArticleThe MAGAZINE feels a special sense

August 1921 -

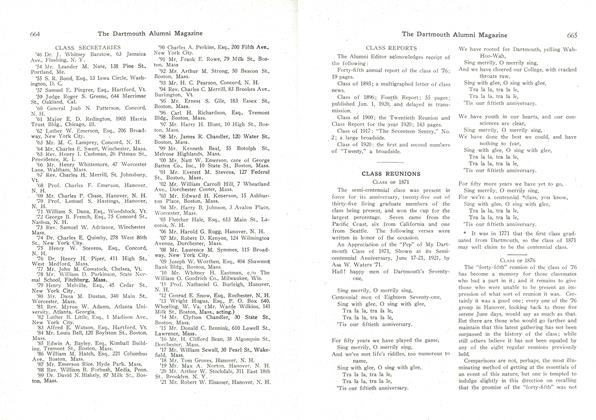

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1876

August 1921 By HENRY H. PIPER -

Article

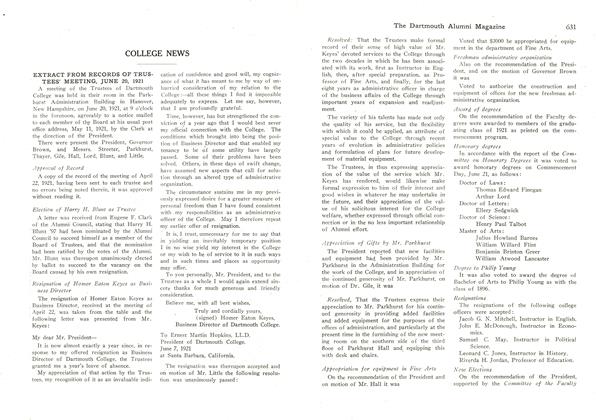

ArticleEXTRACT FROM RECORDS OF TRUSTEES' MEETING, JUNE 20, 1921

August 1921 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1921 By N. G. BURLEIGH -

Article

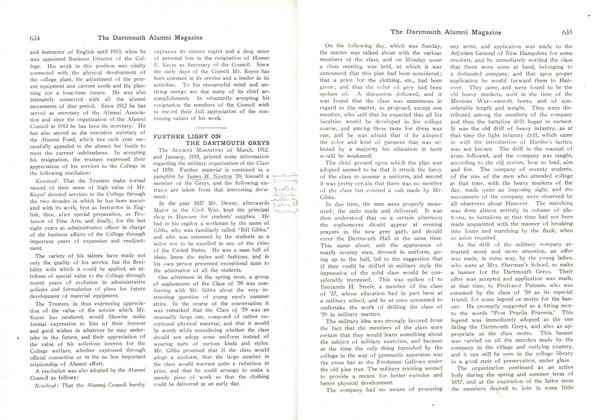

ArticleFURTHER LIGHT ON THE DARTMOUTH GREYS

August 1921

ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS

-

Article

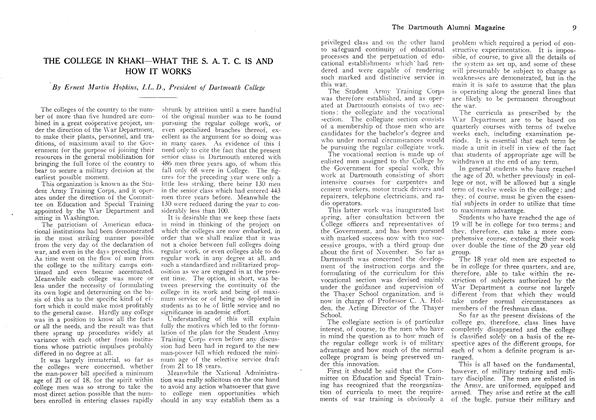

ArticleTHE COLLEGE IN KHAKI—WHAT THE S. A. T. C. IS AND HOW IT WORKS

November 1918 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE: RETROSPECT AND OUTLOOK

July 1919 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE'S RELATIONSHIP TO THE COLLEGE

November 1921 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleAN ARISTOCRACY OF BRAINS

November, 1922 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleTHE GOAL OF EDUCATION

November 1923 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

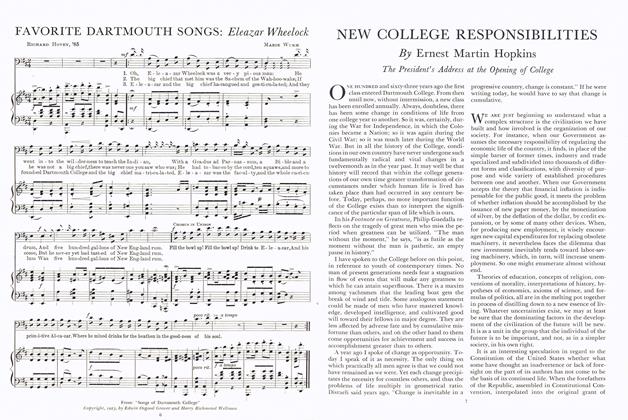

ArticleNEW COLLEGE RESPONSIBILITIES

October 1933 By Ernest Martin Hopkins