Miss Cruikshank, who has prepared the following vivid account, had unusual opportunities in early childhood for knowing and appreciating Rufus Choate. She was born in Washington in 1825 and died in the same city in 1919, and Rufus Choate lived at the home of her mother while serving in Congress. Readers of the MAGAZINE are indebted to Luther S. Oakes '99, a relative of Miss Cruikshank, for making possible the publication of this material. —THE EDITOR.

My acquaintance with Mr. Choate began when I was but five years old, and though the observations and remembrances of a child can scarcely be worth much, yet as my early years were passed under the roof of his brother-in-law, Dr. Sewall, with whom he made his home when Representative and afterwards when Senator, and I was thus associated with him in the every-day intercourse of family life, an interest may attach to them which they could not otherwise possess.

He was a man whose personal appearance was but little affected by the lapse of years; he could never have been handsome in youth, and age had no power over his infinite charm of expression. If you analyzed his mere physical framework you could discern but few beauties. He was tall and loose-jointed, altogether clumsily built and with very large hands and feet; if I may so express it, bovine rather than equine. Nor were his motions graceful. His walk was a slow, elephantine swing that seemed to make little progress, but by its enormous strides rendered it almost impossible to keep up with him. I remember that Mrs. Choate said that she could not walk with him. On one occasion she gave an amusing exhibition of her method of progression if she ever made the attempt: patter, patter, her little footsteps, and then an enormous leap forward to catch up.

His features were thin-cut, but not regular, his eye was small and unsteady, his skin sallow. He was always thin, in later years becoming even haggard, and with very little beard. One beauty he had: his head was adorned with loose curls of the richest, silkiest raven hair. Certainly, even taking these hyacinthine looks into account, I have not described a handsome man, but however plain his form and features were in themselves, they admirably served his turn as vehicles of expression, and no one who felt the charm of his manner and conversation would have wished him other than he was—he was so completely sui generis.

Mr. Choate was highly nervous; insanity was in his family. His father had been so, and his sister, Mrs. Sewall, was insane the greater part of her life. There is no doubt that the dread of this hung over him always. There was much in him that only a knowledge of this fact could explain: his unsteady eye, his trembling hand, his extreme nervous excitability. He could not make the shortest speech in Congress without being unhinged for the day, and usually on such occasions came home from the Capitol and went straight to bed, distracted with headache, his almost constant companion.

He could not endure convivial dissipation. He never used tobacco; late hours were his abhorrence, and he could not drink. Often the day after a dinner party he would be miserable with unstrung nerves and torturing headache, and when asked what ailed him would answer with the fun that never failed him: "The wine that Helen (his wife) drank made me sick."

He has been called an opium-eater. That charge I know to be false. His peculiar constitution would have sunk immediately under the fearful physical and mental alterations induced by that drug. Yet I am not surprised that many thought so who did not know the true state of the case. In truth, his habits were most moderate and regular. He ate but little, and was fastidious as to the delicacy rather than the richness of his food. If it was possible he was in bed by nine o'clock and up early enough in the morning to take a cold sponge bath and walk several miles before breakfast. And this he did in all weathers.

His intense devotion to study forms a large part of the popular idea of the man. It may not be so well known that even while he was in Congress it never flagged. I once hastily united with others in calling him a literary debauchee. I have changed my mind. I have no doubt that the soothing influences of books supplied to him the sedative he needed; that study was the Lethe in which he forgot the rude encounters of life which might otherwise have proved too much for him.

A friend of mine—one who knows all the circumstances—has told me that he once heard Mr. Choate deliver an address before a library association, in which he touchingly alluded to this fact. I have forgotten the very words, beyond: "Had it not been for books, this poor brain...." It is easy to infer the idea the rest of the sentence must have conveyed.

He never sat to read or write. In the later years of his life I am told that he had some kind of support to sustain him at his desk, but when I knew him he always stood bolt upright. He had a desk at home and also one at the Capitol, the latter behind the Vice-President's chair, that no time might be lost during prosy debates.

Politics and Law were, of course, his chief studies, but some Latin, Greek and French formed part of every day's reading, and books in those languages always lay convenient on his desk. He conceived it to be a duty to be conversant with literature in its highest developments, and to keep abreast also of the current. This, of course, included first-class fiction. He had a high appreciation of Scott's genius, and always looked for the last thing from Dickens with interest.

His habit was to go to the Senate and come home only to bury himself in his books. At mealtime only was he seen by the family, and not even then, if he had experienced rather more excitement than usual and was forced by headache to go to bed. When that was the case, I, his recognized nurse, was dispatched to wait on him. The answer to my knock was usually something like this: "Come in, my dear child. I am tired down to my very boots, and my head aches villainously. I am dead and buried for a dish of tea. A dish of tea, Marge, for the love of the Virgin Mary!" Sometimes I was told that if I would procure for him this much-desired refreshment, "I never should know what he would give me!" or that "the entire solar system should be concentrated into one glittering coronet for my brow!"

When the tea—"that imperial drink" —as he sometimes called it, had been disposed of, "Could you bathe my head? came next. This, of course, I was glad to do by the hour, sure of my reward in his sparkling conversation.

This course of overwork he dared not pursue too far. After weeks of intense application he would surprise and delight the family by spending an evening downstairs. That was a holiday indeed! I never knew him to be out of humor, and at such times he would abandon himself to the most waggish drollery, or pour forth witticism after witticism in sparkling profusion. I believe I never heard him make a pun: his wit was the genuine Attic Salt—the essence, not the form.

Occasionally Mr. Choate would take a fit of quotations. The evening long he would scarcely speak except in the most apropos or the most oddly applied quotations: in prose or poetry, from every author, ancient or modern, known or unknown. The passages were so pat that we used sometimes to accuse him of manufacturing them to suit the occasion, but he could always fall back on his authority and give chapter and verse. The long ago forgotten poems of Hannah Moore, old plays, old newspaper articles, modern poetry and fiction, the classics and Laura Matilda, history and the penny ballad, Shakespeare and Punch, the Bible and Mother Goose—all seemed to have been committed to memory most carefully, for he never was caught in a mistake except in quoting from the Bible, and there he erred intentionally when he quoted it for amusement. He once reproved a member of the family for using a text to point a jest, and when he apparently did the same she turned upon him. To her astonishment he said, "I was not quoting the Bible." "Why Mr. Choate!" "Certainly not; my Bible reads" so and so, giving the exact quotation, from which he had varied a hair s breadth to save his conscience.

A partial explanation of his omniscience in literature is found in his habits of reading. He would read a page in less time than it takes some men to turn it. He said that he had trained his eye to run down the middle of the page and detect the important passages; to these, and these alone, he gave heed. It seemed inconceivable to slower minds that he could gain an idea from the process that he called reading. A book would be dispatched in about the time it would take an ordinary man to turn the leaves, and yet he had taken in the whole—had read, marked and inwardly digested it aye, and if needs be could quote it from title page to finis.

There was always a fine atmosphere of taste and culture about him, perceptible even to a child. He never set himself to talk down to one. I gratefully remember this in his intercourse with me, and look 'back to him as one of my best teachers. He took great pains, and always in the pleasantest way, to correct my pronunciation or any provincialism contracted from the swarms of darkies always in our kitchen. I was going downstairs before him one day and said, "Excuse my taking précedence of you,. Mr. Choate." "I will, Marge, if you will say preced'ence." He once lost his slippers and I was the lucky one who found them. I held them up in triumph, with "Are these them, Mr. Choate?" "Those are they," he replied, with a slight emphasis and a significant smile, that fixed the construction in my mind forever.

While I was attending to his wants— bathing his head, etc., he was forming my taste. His mind could not rest even when he was prostrate on his bed. He would often burst out in some beautiful description or impassioned apostrophe which would at once arrest my attention. He was always ready to explain, and in this way many a treasure was added to my storehouse. I thus recall passages of Patrick Henry's speeches, Coleridge's "Hymn in the Valley of Chamouni", Bryant's "Evening Wind" , &c. Or sometimes it was only a few striking lines, such as:

"I care not, Fortune, what you me deny; You cannot rob me of free Nature's grace; You cannot shut the portals of the sky, Through which Aurora shows her brightening face."—

"Thou art my dear and honorable wife, As dear to me as are the ruddy drops That visit this sad heart."-

"Oh night, And storm, and darkness, ye are wondrous strong."—

"The morn is up again, the dewy morn, With breath all incense and with cheek all bloom."—

He certainly gave me my first taste of the magnificence of Childe Harold, but I do not remember that he quoted much from. Byron—he greatly disliked the man.

I remember his once saying, "I shall never forgive myself, Marge, for one omission. I delivered a lecture once on Poland (that was in the days when 'Poor crushed Poland' was an enthusiasm) and I overlooked the inimitable appropriateness of the lines from Romeo and Juliet:

'Thou are not conquered; Beauty's ensign yet Is crimson on thy lips and in thy cheeks, And Death's pale flag is not advanced there!'

I shall never forgive myself."

He suffered excessively from heat, and in July and August afternoons of the long session he would come home from the Capitol completely prostrated. Denouncing the weather as "Tartarian!"— "Phlegthontic!"—he would call for his panacea, a dish of tea, which, if we were alone, he would raise to his lips with "So saying, he applied his black beard to the pitcher and took thence a much more moderate draught than his encomiums seemed to warrant." "The Holy Clerk of Copmanhurst" was a great favorite of his. He did not usually indulge in the whole quotation: after having excited my curiosity and sent me to "Ivanhoe" to satisfy it, he contented himself with a waggish expression and "So saying he applied his black beard—".

As is well known, Mr. Choate was no radical, and however he might differ from men from other sections of the country, he always wished to be on pleasant terms with them socially. He rarely lost patience with them, but I remember one instance.

In a long debate Mr. Benton constantly reiterated statements which Mr. Choate held to be false. Talking it over at home with a member from Ohio, Mr. Morris, the latter said, "Do you suppose that Benton can believe what he has been asserting for the last three days?" "I have not a doubt that he does," answered Mr. Choate. "If a man will assert three times a day for five years that there are forty tom-cats in that corner of the room, he will end by believing it."

Just one more anecdote and I will end. I am giving you some extracts from "Recollections", put together many years ago for a Kentucky admirer of Mr. Choate.

There was a grand wedding in Virginia —at Arlington, I think—to which many members were invited. Mr. and Mrs. Choate and Mr. Morris took a carriage together. The ceremony was performed by the Rev. Thomas Bloomer Balch, a very eccentric minister, who manifested his eccentricity in his dress as well as in non-important things. As our party was returning, gossiping over the events of the evening, Mr. Balch's appearance came up for discussion. Did you ever in your life, Choate, see such a collar?" "Oh, that is easily explained. The man manifestly had his shirt on wrong side up!"

RUFUS CHOATEFrom the engraving by John Sartain

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

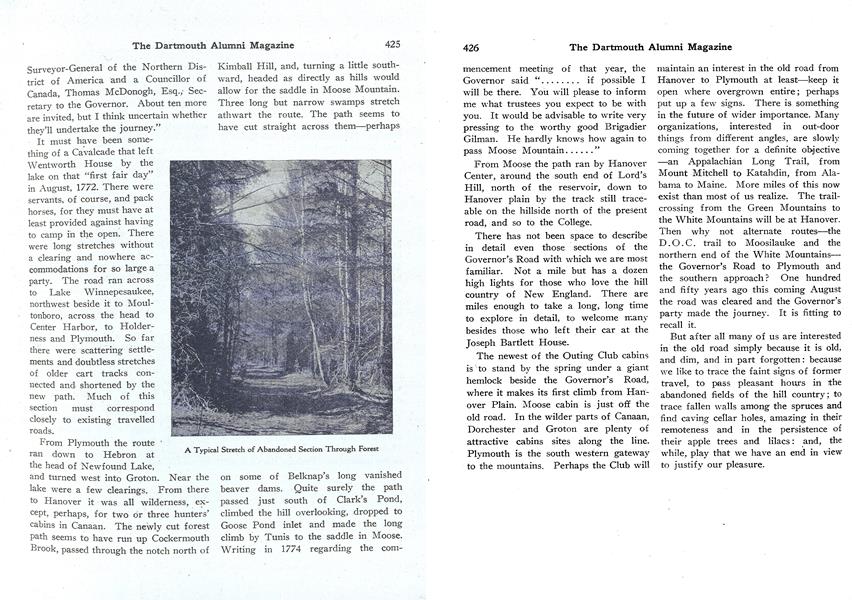

ArticleTHE GOVERNOR'S ROAD

April 1922 By NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH -

Article

ArticleRecent criticisms by President Meiklejohn of Amherst College directed toward

April 1922 -

Sports

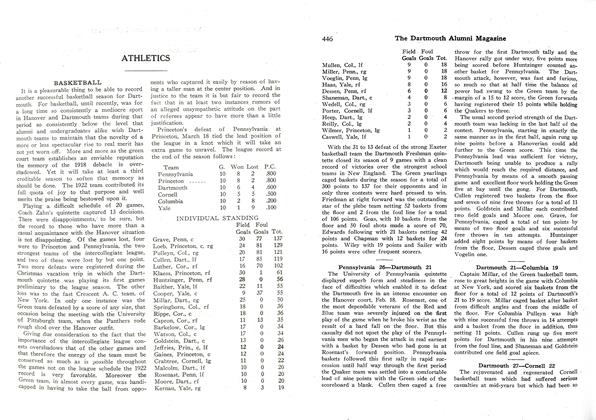

SportsBASKETBALL

April 1922 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

April 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleNOTES

April 1922 -

Sports

SportsFRESHMAN BASKETBALL

April 1922

Article

-

Article

ArticleCONFERENCE OF SECONDARY SCHOOL PRINCIPALS AND SUPERINTENDENTS

June 1916 -

Article

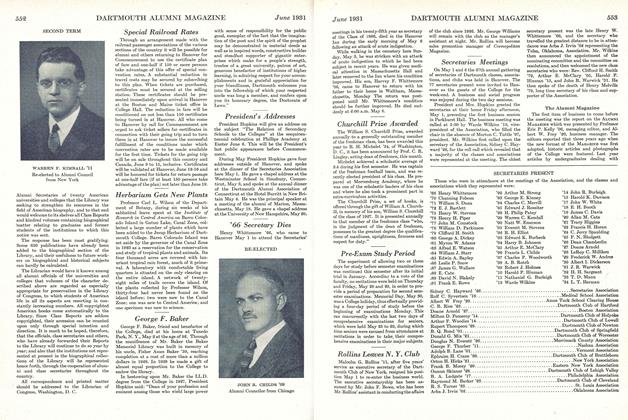

ArticleWhite Church Burns

June 1931 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Services for Dartmouth Menin Service

October 1943 -

Article

ArticleMisterogers of TV Land

APRIL 1971 By B. B. -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH DAILY

APRIL 1932 By E. H. Hymen '33 -

Article

ArticleBriefly Noted

OCTOBER 1970 By J. H.