The following article is in substance the address delivered before the Secretaries Association in April, 1923.

I left here in January, 1912, and returned in September, 1922. I was, when here before, minister of the White Church, officially known as the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College. President Hopkins asked me to come back. His conception of what he wanted done was set forth in a very fine letter. He said he felt the college owed it to her students to teach them to "capitalize their souls." He thought it necessary for every man, irrespective of any theological views of the meaning of salvation, to have a religion. And he thought I would be able to contribute that end.

I have been asked to give you my impression of the changes which have come about in the ten years between my leaving and my return. I need not speak of the multiplication of buildings. That is obvious. Nor of the increase of students - that is obvious too. The material and numerical growth of the College has been splendid and very impressive. But you can see that as well as I. Rather should I speak of those developments which are not so easily recorded in terms of arithmetic, and those changes which record an impression on one's heart as truly as on one's eye.

was still in harness. And what a flavor they imparted to our life! They did it by a certain persuasive picturesqueness of their personalities. They did it also by the character of their homes. They did it by the goodness of their lives. The first one to go was the beloved Dr. Smith who was to me as a father, and from the sweet reasonableness and Christian grace of his life I received an impress which I hope I shall never outgrow, even as I am sure I shall never forget him: There was Prof. E. J. Bartlett, happily still with us though retired from active service, whose words ever had a crisp tang to them and who dispensed wisdom with an appetizing relish, and who continues to do so in leisure as he did in service. There was that familiar figure who rode a bicycle about our streets, ever forgetting his appointments, leading the students through the mazes of mathematics and dispensing justice as judge of our precinct — good old "Tute" Worthen. There was Professor Sherman, Prof. Hazen, Professor Campbell and "Type" Hitchcock — and there was that strong man, loyal friend and valued counsellor — Prof. John K. Lord. Last fall we lost another, beloved of us all for the gentleness and tireless fidelity of his character, Dean Emerson, When I was here before, of the men of the "old school" in the faculty, a remand during the summer Mr. C. P. Chase for years our friend and adviser. Professor Colby resides here still, though also inactive. And who that had the privilege of knowing Prof. C. F. Richardson can ever forget the charm of that beloved teacher! Last and first of all we miss him who was our Leader and Benefactor, blessing us with the things of the spirit of which was at once the depository and the dispenser — President Tucker. Happily some of us still have now and then a chat with him in his home on Occom Ridge. No man who had lived in Hanover when these men were doing their work and living their lives here could fail to miss them deeply when he returned to find their positions though not their places filled by others. Hanover has changed by their passing from the stage, even though their work is being carried on by able successors. For there was a quality about the personalities and characters of these men which we miss in ourselves, a quality which came from the discipline and nurture which shaped their lives and which has given way to a new discipline and nurture in home and church and school which has yet to prove itself as efficacious for the making of men as the training of former days.

The next thing that impressed me has been the obvious improvement in the appearance and general deportment of the students. I well remember coming over Main Street one day in the former period and being shocked by the torrent of specially offensive profanity which came pouring out of the windows of Sanborn Hall in tones easily audible half a block away. I was not unfamiliar with profanity; I had been a college student myself. It was the quality of this profanity which rasped on me. Of course, it was unfair to judge the whole college by it. But a place is often colored by its minorities, and the impression stuck. And the incident was not so solitary that it could be called exceptional. It was tolerated if not sanctioned by the premium which the college of that day put on hardness. And that attitude was the heritage of former days when in its excessive isolation and provincialism the college, situated in the wilderness quite apart from the refining influences of cosmopolitan society, inevitably took on in its manner of life some of the ways of the woodsman. Hard living is usually if not inevitably accompanied by hard liquor and hard language; witness the life of sailors and soldiers and the patois of the fo'c'sle and the barracks. But it was not only reprehensible but anomalous in an institution devoted to the development of culture. In dress the same spirit expressed itself. And in other ways.

It was a great source of gratification to note the tremendous change of the college in this respect. Not that these lads today never break the Third Commandment. Not that they are always reproductions of the House of Kuppenheimer page in the Saturday Evening Post. But they have made a place in their life for the amenities and the arts as was not done before. I cannot understand the criticism of some who recall the "good old days" with such sentimental admiration and regret this change in the manners and dress and ways of the men. There is a great fallacy in the esteem of hardness. It is that if a man is not hard, he must be soft. That is not true. If a man is not hard, he may be gentle, and the gentleman is a man of strength, not of softness. Don't think for a minute the modern Dartmouth man is soft. The granite of New Hampshire has not ceased to function. Only the granite of New Hampshire suffers nothing for being polished. It takes a fine polish, and if this granite is to be used as pillars of court houses, of halls of government and churches, we prefer it polished. When men praise a period for producing rough diamonds they fail to remember that the value of a diamond lies not in its roughness. And that a man who is rough is not necessarily a diamond. The Dartmouth output of the present has just as many diamonds in it as ever.

What has brought this about is not easy to define. One thing is the development of music here. We have a strong department of music and music holds a place in our life which it never used to. We have a society on the Campus called The Arts, which has been active in promoting interest in things aesthetic, spe- cially in literature, the drama and music. The general trend of the times has not been ignored up here. And lest you think we have so emphasized indoor, tea-drinking aestheticism as to forget out- door athleticism, don't forget that two new features of Dartmouth life which have been born since 1912 are the gymnasium, which is a very busy place, and the Outing Club which is the pioneer among undergraduate organizations of the sort. Dartmouth is an out-of-doors college - it is fine to see the boys on skis and snowshoes and to find them rushing out to the cabins over the week-ends. In fact one feature of our undergraduate life which we can regard with no little satisfaction, and which is an asset of our rural remoteness, is that our week-end parties are held in cabins rather than cabarets.

Furthermore I think the modern undergraduate is doing far more thinking than his big brother of ten years ago. I have been impressed with the intelligence he shows in current questions. The development of the courses in the social sciences goes far to explain this. Recently we were favored with an anonymous leaflet criticizing the college pretty much in toto, and with personal specifications — I was one of the specifications. The issue did more credit to the ideals of the unknown editors than the manner of their critique, which was so intemperate and self-superior that it frustrated its own purpose. But it said Dartmouth is turning out "300 Babbitts a year." Now, that is not so. These lads in their impatience with their fellows expected too much from the average man. They have not learned what some of us learn very slowly, that when you are dealing with youth, you have to postulate youth. We are not yet a school whose atmosphere is charged with enthusiasm for scholarship. But there is a good deal of serious thinking here, and it will grow. In fact I feel that many an undergraduate is suffering from mental indigestion. New ideas are being fed to him dangerously fast.

And if I should be asked to characterize in a phrase the change in the intellectual life of the students since 1910 and earlier, I should say "The Decline of Authority." It is no exclusively local symptom. It is true of youth everywhere. It expresses itself in various forms. The war hastened it, but did not cause it. It was coming. It is the note of every age of transition. It has brought with it at least two developments in our youth. One is the increase in the spirit of non-conformity. The other is the development of independence of thought, and frankness of criticism and expression. These men now are mostly in the category of the men from Missouri. They take nothing on the "say so" of their elders. They have a much-reduced regard for their seniors. Perhaps the war in which youth played so essential a part gave them this somewhat exaggerated sense of their own sufficiency. They say, inarticulately or subconsciously, "The older generation got this world into a tragic mess and summoned us to help them get it out." But whatever the cause, it is here. In my day I took a great deal for granted as established and confirmed truth, guaranteed it may be by the church, or by our fathers in statecraft, or by the learned men who proclaimed these teachings. Who was I, a mere youth, to question their findings ? But today while these youth are not discourteous to their seniors, they have the feeling that they will cash no checks on the Bank of Truth simply on their seniors' endorsement. And why should they ? Can't they see a world floundering around in problems for which these same seniors have no positive solution? And is there not a tremendous gam in reality and candor in this new point of view? Of course it has its dangers, but it is full of promise. How often the old regime of authority stifled independent thought and still more frank expression! I attended a session of our Liberal Club one night this winter, and the topic was "present tendencies in religion." Every man present was invited to express his views, and we all did. And we had all shades of opinion from Roman Catholic orthodoxy to Near-Atheism. It was splendid. I doubt if such a meeting would have been possible in my undergraduate days. Few of us thought deeply, and those who did dared not proclaim widely their views if they smacked of social or religious heresy. But with the splendid spirit of tolerance which our president inculcates here, men may think for themselves and say what they think. Our business is to help them think right. Of course some of their opinions are irritating, and very youthful. And one must expect certain excesses in criticism or radicalism: or aestheticism. But there is a net gain for reality and courage and truth. Yet it makes it quite a little harder for some of us. who teach and preach.

And so I suppose in closing you want a word about the chapel. It is not the same as you remember. Dr. Tucker is not there. But the situation is not without encouraging features. The Sunday evening service is a credit to the college. It is a challenging joy to me. The daily morning service is — an uncertain proposition. The only justification for it is its religious value. It is not justified as a means to get men up in the morning. I refuse to take a good salary from the college to serve as an alarm clock. Sometimes I feel that the service does avail to impart a bit of subliminal inspiration or some thought of real value for masterful living. And again I doubt its value. He who conducts that service not be too thin-skinned. Again one must not forget in dealing with youth to postulate youth. Nor must one forget that the first Christian seed found stony ground and thorns and wayside birds. The ground is too often covered over in morning chapel by the Daily Dartmouth and the seed does not find any root. But of course there is — thank God—good ground.

But after all our interest in the chapel question is deeper than mere details of regulations. It is born of the fact that we all feel that if we have all wisdom and knowledge and understand all mysteries, still we lack something very vital. Yes, the world needs brains. The aristocrasy of brains today is none too populous. Mr. John Jay Chapman in a recent Phi Beta Kappa address said that "there are only 1207 people in America who can read a good book." I don't know why he picked that number. But some questions come burning in upon us which we can't escape. What do we add to the boys of this college to what they bring from home in spiritual life? Are we creating a spiritual life here, or merely reverencing it? Do they go out from here with a distinctive spirit whose notes are faith in God, appreciation of things beautiful and true, hope for the future. love for their fellows which will constrain them to live as servants and friends and not as exploiters? We should. I believe in the Christian religion as indispensable to the reclamation and regeneration and salvation of the world —and you can interpret those words politically or from the point of view of economics or sociology, or metaphysics. I want these men to believe in God, for a faith in God serves as nothing else does to ground and establish in reality the values of culture and morality which we are trying to make these men esteem. And the world is crying for men of trained minds who are also great of soul and heart. Look how during the war the peoples turned again to the words of Lincoln! I believe it reasonably demands of the colleges to produce such men. We sing that "the world will never have to call on Dartmouth men in vain. ' And I hope that the answer which Dartmouth gives will not be simply trained business minds from the Tuck School, or engineers from the Thayer School, splendid as this answer may be, but men completely furnished unto the good and urgent work their day and generation needs to have done, and they will not be completely furnished thereunto if they are lacking in faith and all the other virtues and graces of the spirit of which it is the ElderBrother, if not the parent.

By REV. FRANK LATIMER JANEWAY, College Chaplain

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE GOAL OF EDUCATION

November 1923 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleDartmouth College has entered upon

November 1923 -

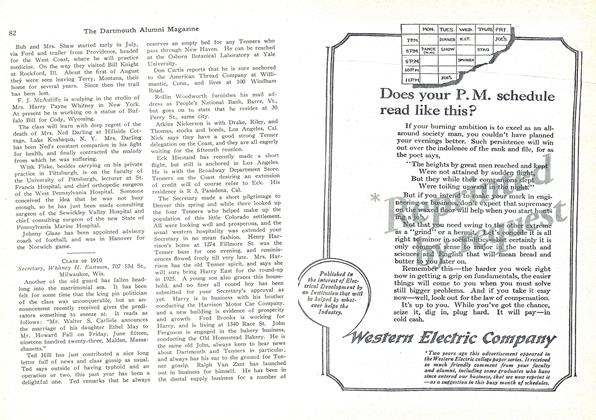

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1923 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

November 1923 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1923 By Ralph Sanborn -

Article

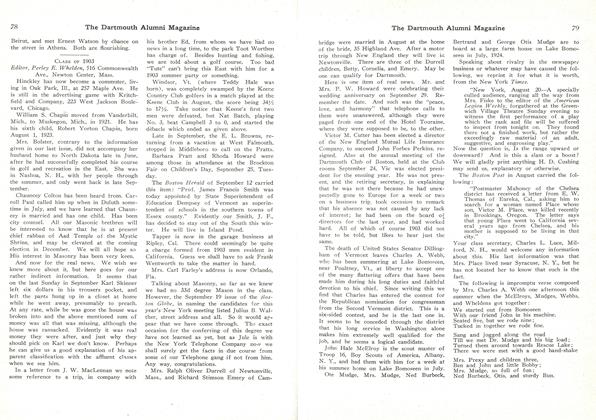

ArticleENROLLMENT FIGURES AND STATISTICS OF CLASS OF 1927

November 1923

Article

-

Article

ArticleSENIOR CLASS ELECTIONS

April, 1912 -

Article

ArticleClass Rankings in 1948 Fund Participaton

October 1948 -

Article

ArticleDeaths

OCTOBER 1981 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

October 1941 By William P. Kimball '29 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

MAY 1957 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29