Dr. J. W. Barstow at the advanced age of 97 last month, there passed from this earthly scene the oldest living graduate of the college; and since this venerated position can never be vacant, there now succeeds thereto Leander M. Nute, of Portland, Me., who was born in April, 1831, and who is therefore nearly 92. The interest of the late Dr. Barstow in the affairs of the college was remarkable and was sustained down to his closing years, even after the natural feebleness of body precluded his pilgrimages from New York to Hanover. He was. universally esteemed and- loved. There was vouchsafed to. him a longer span than falls to most; and in it he gave full account of his stewardship, alike to the college and to the community in which his lot was cast.

A recent article in Scribner's Magazine from the pen of Mr. W. B. Shaw, alumni secretary for the University of Michigan, discussed the tendency of alumni bodies to take a more direct part in university and college affairs, pointing out that an organization originally designed to perpetuate old and agreeable associations of youth has grown to include the design to take a more or less active and influential part in the management of college affairs. This development Mr. Shaw appears to regard as on the whole desirable -and useful, although admitting that it might be overdone and that the influence exerted cannot be guaranteed to be always beneficent. Meantime the editor of Scribner's Magazine, taking up the subject, seems inclined to make an issue with Mr. Shaw, holding that the proper function of alumni is to let the college alone, abstain from illinformed attempts to influence the college policy — which would much better be directed by the experts on the ground - and in short resume the original notion of alumni meetings, which was a modification of the meminisse juvabit principle, plus a duty to contribute at need to college funds.

Of course the whole question turns on the power of the alumni to be of real assistance to those experts actually on the ground. The alumni are unquestionably recognized as an integral part of every college, and a very important part when it is a question of passing the hat. The only question now raised is the extent of their capacities to be more of a help than a hindrance in the management of the college business, or in the direction of policies, by faculty and trustees. Mr. Shaw, while admitting that at times the notions of alumni may be mistaken and even detrimental, seems to believe that in the main this development of alumni activity is for the good of the service. The editor of Scribner's appears to think that the benefits to be derived are so inconsiderable, when set against the potential detriments, as to warrant a distrust of the whole theory. Let the alumnus come back to reunions, attend games and alumni dinners, supply money as liberally as possible when asked to do so—and for the rest, leave it to the trustees, faculty and students to work out their own salvation in fear and trembling, without gratuitous advice from old graduates, who can hardly be in close enough touch with the going concern to be competent directors!

Is it not entirely probable that, as is quite usual, the truth lies between the two extremes ? It is entirely clear that the judgments of alumni on matters of intimate domestic detail would be probably valueless as against those of president, professors and trustees, partly because of a lack of sufficient information and partly because of the natural change of customs since the alumni were in residence. But it is by no means so clear that in shaping the general policy of any college — such for example as may affect the broad scope and purpose, the size, the general aims to be sought for fulfilment — the alumni judgment is to. be despised. Resort to it can be grossly overdone — granted. But we doubt that any college fulfills its modern mission with much prospect of success if it does not invite and respectfully consider the collective judgment of its graduates in matters where their judgment may easily have a direct and important value. In some aspects it is peculiarly desirable to awaken in the alumni breasts a sense of personal responsibility for the continued well-being of the college. Otherwise, one drops too easily into the unworthy feeling that the only thing to be considered is the success of the institution in athletic matters^ — the easily besetting sin.

Every college has experienced, in its degree, the sort of episode of which so much has been made of late in the case of a Pennsylvania institution of learning —a case where alumni dissatisfaction with the sporting; record led to differences of opinion concerning the coaches and finally to the resignation of the president and one professor. This ridiculous magnification of a small matter has been made the subject of sarcastic editorial comment all over the country. Fairness compels the admission that it seldom goes quite so far, or has so dramatic a consequence; but it will probably be admitted by any graduate that his circle of alumni acquaintances embraces many a man whose one idea is that the college should have a strong football team and win, if possible, all its games. One may hardly attend an alumni dinner without perceiving the exaggerated importance which athletic prowess assumes, or without hearing some enthusiast proclaim that the most important thing in life is to insure victories and give the college its true place at the top of the athletic heap. It thus becomes a question whether, if the alumni as a whole assume a greater and greater part in college management, this prospensity will color the management in ways hardly to be commended; or whether the result will be to awaken the alumni by dint of added responsibilities to the larger meaning of education.

It is our present belief (one learns by experience how beliefs may be altered by the tests of time) that the net effect of a closer union between alumni bodies and college managements is beneficial and tends to sober those who otherwise know of the college only through the sporting pages and occasional appeals for funds. At all events the feeling grows that the demands upon alumni for financial support imply some compensating duty on the part of colleges to listen to alumni voices in matters where alumni voices speak with reasonable pertinence. It is peculiarly true of such colleges as our own, where a substantial part of the board of trustees is of alumni selection and constitutes a form of representative government. All who have seen much of the workings of initiative and referendum recognize that such things have their limitations, which are soon reached, and appreciate the virtues of trusting to the representative, once he has been selected, to do his duty without constant or meddlesome supervision on the part of the electors. But one retains, nevertheless, a wholesome regard for the rights of the represented, in the rather rare cases where an intelligent verdict is to be looked for by a popular vote of ratification or rejection; or where the representative himself feels the inadequacy of his mandate, which he holds in trust for the alumni, in -the case of a debatable policy which is certain to have a vital effect on the college future.

No one can escape the fact that alumni representation on boards of college trustees — whether for well or ill — is increasing and has come to stay. Like other forms of democracy and divided responsibility, it has the defects of its qualities. There are certainly dangers in the growth of alumni influence, to offset the elements of greater safety and the benefit due to a livelier acquaintance with the college's needs. One must take some things on faith and strike as just a balance as may be possible between the bane and blessing. The present editors of this MAGAZINE incline to sympathize rather with Mr. Shaw's original article in Scribner's than with the editorial reply to it — a feeling which we find to be shared by the alumni publications of other colleges and universities. No one denies the possibilities of occasional harm so stressed by Scribner's Magazine; but one does deny the postulate that the harm so far outweighs every conceivable advantage as to make alumni participation in college management a work of folly.

With the new selective system of admissions to Dartmouth College in mind, it seems in order to insure beyond the peradventure of doubt the thoroughness and quality of preparatory schools, on whose ranking of applicants the college must rely for its estimate of scholarship. If a boy manages for three years or so to stand high in his preparatory classes, something depends on the exigence of the schools in which this high standing is maintained. At the recent meeting of the Alumni Council in New York it was wisely decided to make a survey among various preparatory schools to discover what might be the "reactions" of their principals to the new system, as it reveals itself in actual operation. The opinion at Hanover appears to be that the selections made under the new theory of admissions indicate an enhanced quality of the entering class, so far as may be judged by the first few weeks of experience — i.e., that it seems to reveal on first acquaintance a commendable improvement over older systems. One must naturally make such affirmations with due caution. It is rash to judge of ultimate results by reference to one initial year, and rasher still perhaps to judge of any new class by reference to its initial appearance on the campus or in class rooms. It may be said with safety, however, that thus far nothing is discernible to shake the faith of the college managers in the new selective system as tending to provide the college with an entering class of the kind it desires — that is, a class composed in the main of appreciative young men, alert to make the most of their opportunities, representing as fairly as possible the entire country, and giving promise not only of developing educationally but of adding to the net morale of our American citizenship.

Alumni and associations of alumni living at a distance are duly cautioned against the too ready bestowal of their names as sponsors for social events bearing the name of Dartmouth dances, or similar social functions. One or two unfortunate experiences have led the Alumni Council to look into this matter and to urge that the college name be reasonably restricted to its appropriate avenues of use in such affairs. A dance or other social event conducted by a Dartmouth graduate organization, or in connection with the visit of any approved undergraduate organization, such as the Glee Club or one of the athletic teams, affords as a matter of course a wholly proper and appropriate occasion for the use of the college name. But the name should certainly not be employed when the dance or other function is widely divorced from any genuine college activity, or is conducted for personal profit, or so delusively camouflaged as a college affair as to arouse misconceptions or reflect potential discredit on the college itself. Individual alumni are also cautioned against the too easy allowance of the use of their names as patrons of such events as they may not know all about and find to be properly designated as Dartmouth parties. In this we have no doubt a sensible and hearty cooperation will be accorded by alumni of the college wherever situated.

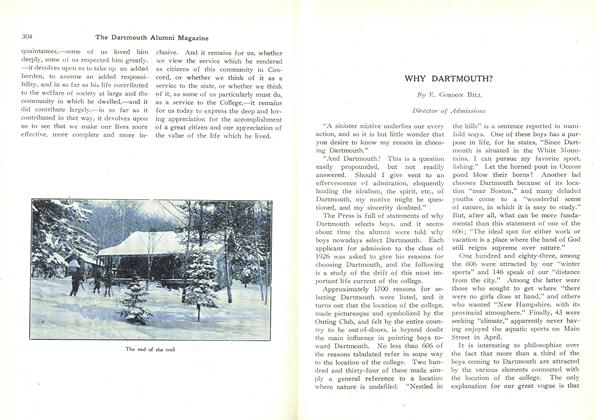

At this season of the year attention naturally directs itself toward the winter activities of the Outing Club, winter sport being one of the distinctive attributes of Hanover. It has been established by investigation that a very considerable proportion of the recent students selecting Dartmouth as the college of their choice have come to us because of the decisive allurement of this health-giving out-of-door feature of the college life.

Times change and we change with them. The present emphasis laid on out-door winter life is a modern variant of the hard old days when winter sports were almost unknown at Dartmouth, but when the rigors of the northern climate were celebrated none the less as adjuncts for producing a peculiarly sturdy and hardy manhood. In those days one made no pretense of enjoying the frozen environment. One suffered and was the stronger for it — and proudly told the world about bathing in water from which it was first essential to clear a coating of ice. It is merely another version of that remark so common in current Far Western fiction which extols the "great open spaces where the men are men." The Dartmouth of today finds the old-time virtues in the long winter months, but it seeks them actively rather than passively. It goes forth into the woods, over the drifts and crusted plateaus, up the sides of silver-mantled mountains, grappling joyously with the cold.

This is one of our great natural advantages — perhaps the very best incidental "advertisement" the college has. It is not a rash thing to surmise that the Outing Club and winter carnival features together incline more men to come to Dartmouth than a string of victories on either the gridiron or the diamond.

What has been said elsewhere above as to the benefits possible to be derived from intelligent alumni participation in the government and direction of the college prompts a closing word with respect to the pending discussion of methods for selecting the alumni trustees. This is a very important matter in which the alumni are directly and very properly interested. It is. further a matter which should be considered dispassionately and decided intelligently, after hearing all that is to be said for and against the various alternative plans. The MAGAZINE expressly refrains from indicating any preference among the three suggested systems recently discussed by the Alumni Council and later to be reviewed and sifted by the Association of Class Secretaries at its April meeting. The whole matter comes down to one of securing, from the whole body of alumni, trustees as able and gifted as can be found for the general service of Dartmouth. The end is all-important. The means are important chiefly as enabling the most certain attainment of that end. What we would especially recommend is the constant recollection of the thing we are really after — to wit, the most efficient managers for the college that can be found. There is sometimes a tendency in these discussions to speak as if methods were of more importance than results and that for the sake of a form we should sacrifice^substance. "Whate'er is best administered is best" and it is chiefly important to discover what is, in fact, best administered as a system for procuring alumni trustees, who may at once represent the alumni and advantage Dartmouth.

When in the appropriately critical mood, nothing is easier than to give the fancy free rein to condemn the excesses incident to college athletics. If our own people do it — and they do — how blame the correspondents of the British press for doing the like ? Least of all may one find fault with the New York correspondent of the Manchester Guardian, who has lately considered this phase of American college life; because notoriously the Manchester Guardian is hard to please and it can generally detect the imperfections in human existence with something which often sounds like a pious zest.

This particular correspondent, speaking of the Harvard-Yale football game as unquestionably the "greatest event in the American university year", admits that he did not personally attend the most recent game. He "listened" to it, as it was radioactively described to a street audience in New York City. But even this second-hand treatment has inspired him to a broad column or so of comment on the whole subject of overdone athletics and overdone athletic equipment, which is pertinent enough to reproduce in part, whether we end by entire concurrence or no.

One cannot forbear a chuckle at one manifest slip — for even the correspondents of the all-wise Guardian share with Jove and Homer the propensity to nod — in which the sarcastic commentator speaks of "the 'breckety-ex-coax-coax' of the Yale cheer." Surely as a cultured Briton, presumably bred in colleges where such hideosities as million dollar stadiums do not exist and where the Greek remains in some little esteem, this writer should not do such violence to the chant of the Hellenic frog as "breckety" reveals ! And one posing as mentor in this portentous fashion would do well certainly to avoid confusing the cheers of Yale and Princeton. It is, however, a small matter which one stresses with some amusement only because of the Manchester Guardian's great reputation for accuracy and exigence. The main thesis of the article has more to sustain it.

This appears to be the contention - that the whole business is sadly overdone both on its emotional and its material side. It seems to the writer a curious thing that "the greatest event in the American university year, the one event which brings all America's university graduates into a communion of minds each year, is a football game." It seems curious also to Americans who may pause to think of it — if one admits that this is the "greatest event" of the whole academic year and the only thing that unites all our university graduates in a "communion of minds" — which latter seems to us dubious. It is at least true that all college men, and several millions of men and women who never went to any college, are interested for an hour or two in a game played alternately at New Haven and Cambridge — just as they are all momentarily interested in the World's Series, or a national election. But that is the extent of this "communion of minds." They are for a space all thinking about one thing.

The article seems to us to have more solid ground beneath it where it assails, at least inferentially, the custom of providing huge erections for the spectators — such as the Stadium at Harvard, the Bowl at Yale, or the various forms of colosseum now either in use or in process of construction at divers other colleges - for no other purpose than that of accommodating a football crowd. Of course the Stadium is used by Harvard for certain other purposes, including those of Commencement week; but in the main it is quite true that football is in mind when a college erects such a structure. The football season is brief—perhaps eight weeks — with a game a week, and not always at home either. But let the Guardian's correspondent state his own case:

The Harvard stadium, originally built to accommodate a mere 25,000, was completed away back in 1908. Yale came a few years later. Ohio State University has just dedicated a stadium that is to seat 64,000 persons — in a city of 200,000 (New Haven has less than that). The University of Washington, the University of California, and Leland Stanford University, on the Pacific Coast, are building structures to seat some 60,000 each; Leland Stanford expects to obtain funds with which to build more sleeping quarters for the students from the profits of its stadium.

These colosseums cost immense sums — Ohio State's, $1,341,000 (nominally £269,000), — but they pay. Students and graduates are glad to help to pay for them; the University of Indiana taxed every one of its summer students $100 (£20), and enforced the tax by effective mob psychology, to help to pay for its stadium.

Baseball cannot be played in these structures — it requires too spreading an "outfield." Track meets do not draw crowds in America; cricket is not played here; dramas — except the most enor- mous pageants — are lost in them. They are for football. The football season is October and November — a game a week. In each game eleven men, representing one university, scrummage against eleven from the other. They are amateurs. They dare not play for money, even in vacation time, lest they be disqualified, but they are coached through their classes by sympathetic fellow-students of more brain and less brawn; they are aided to finance their way by easy but "honest" jobs obtained by sympathetic graduates, and they are trained at a team-table and almost nursed by their trainers day and night.

"Professional" football is a negligible matter in the United States, but these games are attended by more people than see a "world series" baseball game; they make enormous business enterprises, and upon their outcome depends the prestige of man)' a university, and for many a stalwart young American the answer to the momentous question — Where shall I go to college ?

That closing remark may be questioned as to its general validity, for we suspect the advertising value of football and its allurement of students to matriculate only where the game is most successfully played are alike exaggerated in the common belief. Experience at Hanover has lately revealed the fact that very few profess to have been influenced in choosing Dartmouth as their college by the records of this one sport. The claims of the Outing Club, with its promise of enlivening winter activity, are infinitely stronger in this regard. Nevertheless football does influence some, where a college has the reputation for specializing prominently in this rugged sport (which, one suddenly remembers, was imported from England and was once supposed to have value there as the training of eminent British strategists) ; and it is quite certain that "sympathetic graduates" do nurse the teams in precisely the way indicated by the Guardian's essayist.

There is more or less of evil, in short, interwoven with the good in connection with intercollegiate athletics; and it is candidly recognized by our own people as well as by visitors who look on with amusement at our ebullient enthusiasm and our costly provision of grandstands for the public, coaches for the teams, and all the gear that goes with modern sport. That still greater crowds in England often witness cricket matches and football matches is forgotten — partly because in those cases it is not so surely an affair of university or school. England's keenness for sports is well enough known to make visiting critics cautious. One remembers the Derby, not to mention certain world-famous university rowing contests! If one may judge by literature alone, our British cousins are quite as much addicted as are American college men to find in the sporting fields a "communion of minds."

The reasons for these exaggerated colosseums are fairly obvious and it is clear the correspondent quoted above recognizes at least one of them — to wit, that these huge stadiums "pay." They pay in many ways, but in direct money alone they pay an astounding dividend which suffices to maintain athletic sports in the estate to. which they have become accustomed. Football, baseball, rowing, track teams — all benefit to some extent from the fact that football, though of very brief autumnal existence, is the prize money-getter for them all. Football has a distinct advantage over the others that it is not forced to compete with professional teams, and is so popular that 80,000 people will gladly pay any price to be admitted to a first-grade performance. These huge stadiums arose in response to a need, like everything else. Whether or not they are appropriate adjuncts to the higher institutions of learning is a question so manifestly academic that discussion of it is bound to be fruitless. If any stadiums are torn down, it will probably be to build greater — not to abolish them from the earth. Alumni do not want them abolished — students certainly do not want them abolished — and comparatively few of the faculty and trustees would really like to see them abolished. If it be an American idiosyncrasy, so be it. Other people have their own brands thereof, and not always more to be defended.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCUTHBERT'S DIARY

February 1923 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Article

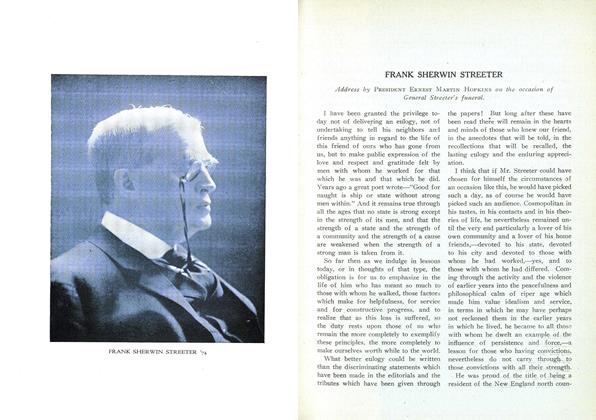

ArticleFRANK SHERWIN STREETER

February 1923 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

February 1923 -

Article

ArticleWHY DARTMOUTH?

February 1923 By E. GORDON BILL -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

February 1923 By Nathaniel G., Martha Flagg Emerson, WARREN F. KIMBALL -

Article

ArticlePROMINENT CITIZENS MOURN DEATH OF GENERAL STREETER

February 1923