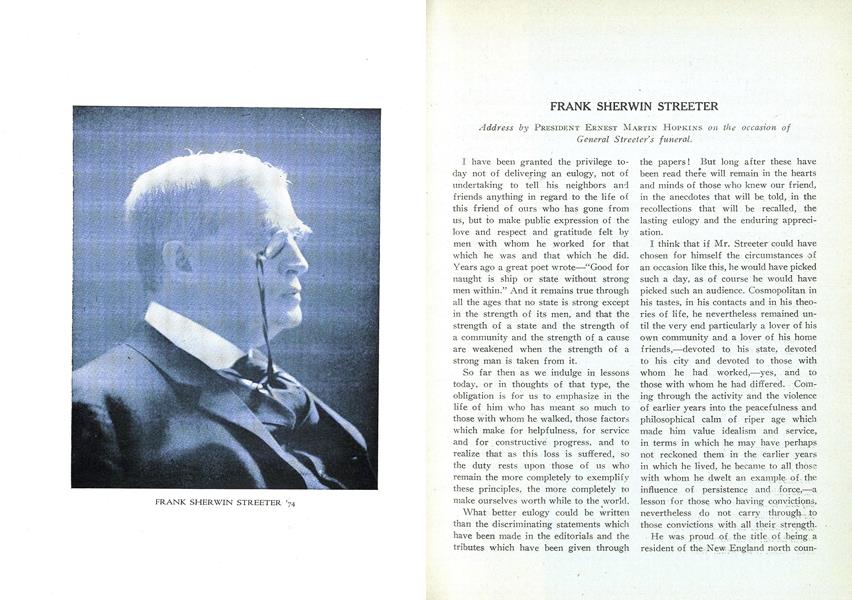

Address by PRESIDENT ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS on the occasion ofGeneral Streeter's funeral.

I have been granted the privilege today not of delivering an eulogy, not of undertaking to tell his neighbors and friends anything in regard to the life of this friend of ours who has gone from us, but to make public expression of the love and respect and gratitude felt by men with whom he worked for that which he was and that which he did. Years ago a great poet wrote — "Good for naught is ship or state without strong men within." And it remains true through all the ages that no state is strong except in the strength of its men, and that the strength of a state and the strength of a community and the strength of a cause are weakened when the strength of a strong man is taken from it.

So far then as we indulge in lessons today, or in thoughts of that type, the obligation is for us to emphasize in the life of him who has meant so much to those with whom he walked, those factors which make for helpfulness, for service and for constructive progress, and to realize that as this loss is suffered, so the duty rests upon those of us who remain the more completely to exemplify these principles, the more completely to make ourselves worth while to the world.

What better eulogy could be written than the discriminating statements which have been made in the editorials and the tributes which have been given through the papers! But long after these have been read there will remain in the hearts and minds of those who knew our friend, in the anecdotes that will be told, in the recollections that will. be recalled, the lasting eulogy and the enduring appreciation.

I think that if Mr. Streeter could have chosen for himself the circumstances of an occasion like this, he would have picked such a day, as of course he would have picked such an audience. Cosmopolitan in his tastes, in his contacts and in his theories of life, he nevertheless remained until the very end particularly a lover of his own community and a lover of his home friends, — devoted to his state, devoted to his city and devoted to those with whom he had worked,— yes, and to those with whom he had differed. Coming through the activity and the violence of earlier years into the peacefulness and philosophical calm of riper age which made him value idealism and service, in terms in which he may have perhaps not reckoned them, in the earlier years in which he lived, he became to all those with whom he dwelt an example- of. the influence of persistence and force, - a lesson for those who having convictions, nevertheless do not carry through to those convictions with all their strengthlie

was proud of the title of being, a resident of the-New England north country, and the New England north country, which stamps, its ruggedness and stamps its individuality upon men, placed its stamp upon him, even as he in return placed his stamp upon the life of this northern New England which he loved.

I sometimes think that we find in human beings, even more distinctly than in the animal world, the instinct of a protective coloring, the instinct to hide those characteristics about which men are apt to be reticent. And in the case of Mr. Streeter I often felt at times, when there was the appearance of sternness, of severeness, of ruthlessness perhaps, that herein was simply the manifestation of a protective instinct under which he sought to conceal the inherent kindness and the sympathy and the tenderness which were in an abounding degree within his heart and soul.

As a portrait painter seeks sometimes in the arrest of an expression to depict a character, as a sculptor sometimes in the capture of a pose seeks to show the continuity of a motion, so I have thought that for merely a moment I might speak of a relationship of his, an idealistic association, the relationship with his college group, as illustrating those characteristics predominant in him which manifested themselves on call in particularly fine and particularly sensitive ways.

For more than thirty years he gave to Dartmouth College a service of the finest consecration, a service whose value was beyond estimate, a service unselfish, a service willing always to bear responsibility, a service desirous of doing for that which he felt to be worth while the maximum which it lay within him to do. And the service which can be rendered by a trustee of a college is a service beyond compare in certain ways, in that it is a self-sacrificing service, in that it is a service which does for others without hope of recompense and without prospect of return. It is a cause which requires a constancy of attention and persistence of effort.

When Mr. Streeter came to the trusteeship of Dartmouth College, it was a prospect uninviting. And I speak not only for myself in stating this, but I speak for three administrations. And I speak with the personal message of President Tucker, who wished me to express for him the sense of indebtedness and obligation which he has aways felt, and who yesterday said to me that he found continuously in Mr. Streeter unplumbed depths of friendship and unclimbed heights of idealism which were not only beyond his own early conception of him but he believed beyond the conception of any man who knew him.

And that which was true in 1893, when he came and lent his spirit of courage and force to the feeble institution, remained true for us who later had to do with the College and its administration, on the board of trustees, unto the very end. It took an imagination, a strength and a vision for a man to see in the half a dozen college buildings, crippled resources and insufficient student body in 1893, the possibilities of the College as they have opened in the years since. And it took not only an imagination and a vision, but it took a nervous energy such as probably no one outside of the board would have any reason to understand. If the time were another, and if there were a longer period in which to talk of these things, incident after incident of the last twenty years could be told indicating how complete his knowledge was of the service which might be rendered to the state and to the nation by making a college render its maximum service.

I believe that great as was his love for the College, and great as was his love for the men who had to do with the College, it was fundamentally because of the service which he believed the College could render that he was willing and interested to commit himself to a degree that made it necessary for him to forego many other things which he might have done, — and to a degree which was incalculable in the amount of responsibility which he would accept.

I speak not only for myself I think, but I speak for each fellow of his on the board during this more than thirty years, when .1 say that the wealth and richness of the endowment which have come to the College through his interest and through his support are something which has enabled the College to make its service infinitely greater and to make its recompense to society very largely more complete for that opportunity which society has given to it.

As the north country weaves into the souls and minds of its men those patterns of ruggedness, of sturdiness and individuality and self-expressive independence, so these men in turn weave it back into the fabric of the life of the society and the groups and the environment within which they live. This friend of ours, who in a busy life found time to keep abreast of the culture of his time, found time to keep himself informed as few men, keep themselves informed on all public questions. The amount of his reading was in excess of that of many men who make reading a vocation rather than an avocation. The contribution which he has made to this community, to this state, to Dartmouth College, is a contribution beyond our ability to value.

There is this further thing to be said, that he was never willing to accept an appointment merely as an honor, and when he took an assignment of responsibility he took it as an assignment of obligation and an assignment for work, something that he was to do for somebody else rather than something which somebody else was to do for him.

In the days into which we are coming I think there is no quality which is to be more necessary, and no quality for which we need seek more eagerly, than the quality of sturdy and vibrant strength among men, combined with the willingness and tolerance to seek wherein service should be rendered and then to render the service with whole-hearted spirit such as was typical of him.

Long ago the preacher said, "If the tree fall toward the south or toward the north, in the place where the tree falleth there shall it be." A great life has been lived, a strong life has been lived; a great record has been completed and is now ours; and it remains, as I said at the beginning, to recall that strength and virtue have gone from us through the completion of this life. So it devolves upon us who were his friends and acquaintances, — some of us loved him deeply, some of us respected him greatly, - it devolves upon us to take up an added burden, to assume an added responsibility, and in so far as his life contributed to the welfare of society at large and the community in which he dwelled, — and it did contribute largely, — in so far as it contributed in that way, it devolves upon us to see that we make our lives more effective, more complete and more inclusive. And it remains for us, whether we view the service which he rendered as citizens of this community in Concord, or whether we think of it as a service to the state, or whether we think of it, as some of us particularly must do, as a service to the College, — it remains for us today to express the deep and loving appreciation for .the accomplishment of a great citizen and our appreciation of the value of the life which he lived..

The end of the trail

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWith the death of the very venerable

February 1923 -

Article

ArticleCUTHBERT'S DIARY

February 1923 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

February 1923 -

Article

ArticleWHY DARTMOUTH?

February 1923 By E. GORDON BILL -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

February 1923 By Nathaniel G., Martha Flagg Emerson, WARREN F. KIMBALL -

Article

ArticlePROMINENT CITIZENS MOURN DEATH OF GENERAL STREETER

February 1923

Article

-

Article

ArticleFRATERNITY ELECTIONS

DECEMBER, 1907 -

Article

ArticleMr. Hopkins Active

August 1946 -

Article

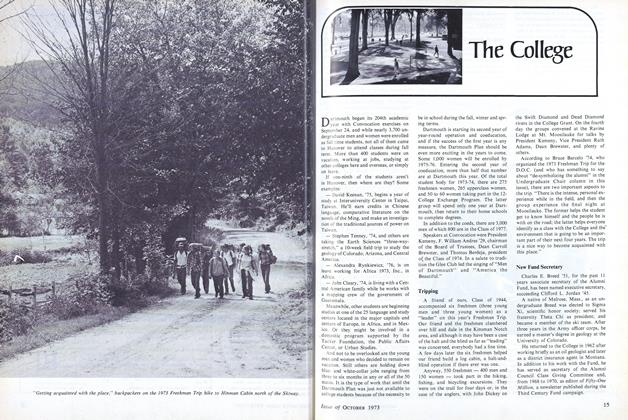

ArticleThe College

October 1973 -

Article

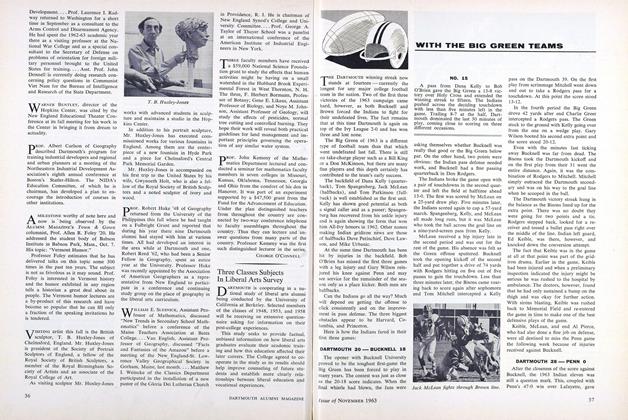

ArticleDARTMOUTH 20 – BUCKNELL 18

NOVEMBER 1963 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleA FRESHMAN'S EXPERIENCE

DECEMBER 1929 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

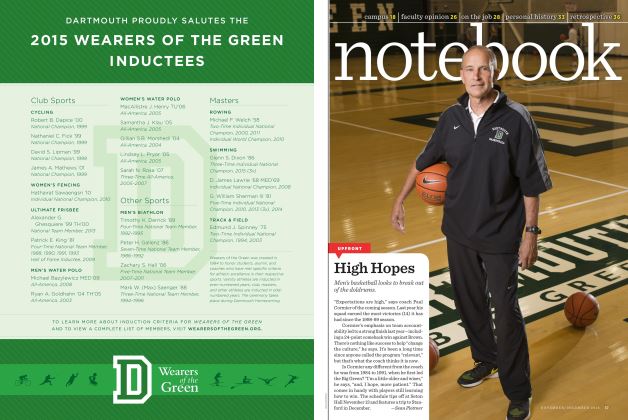

ArticleHigh Hopes

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By Sean Plottner