There was an adventure in Dartmouth journalism which I imagine may be sufficiently interesting to Dartmouth men generally to warrant a fuller statement than has yet been made concerning it. Indeed comparatively little has been written about The Anvil except what appeared in its contemporaries. The paper itself so far as I know, never printed a list of its editors, and that published in The Aegis of that time was incomplete. As it happened that I was connected with the publication for almost the whole period of its existence, I shall venture to give some account of it, only regretting that the absence of printed material will make it necessary that what I say shall very much take on the form of reminiscence.

On January 23, 1873, the first number of The Anvil appeared. It was during the short midwinter vacation which was then in vogue in the College. Organized winter sports had not put in an appearance and the few unfortunate students who for one reason or another were compelled to remain in the almost deserted village could do nothing but hibernate and endure, unless they were ingenious enough to devise some real occupation. In order to make the vacation tolerable a few of the members of the class of 1873, with F. A. Thayer as their leader, started The Anvil. It was their intention to publish only four numbers at weekly intervals but they awoke to find themselves famous. The adventure stirred up a happy reaction from places remote from the College as well as in Hanover, and Thayer and his colleagues determined to make it a permanent institution. Associated with Thayer were Charles F. and Fred Bradley of Chicago,. William P. Cooper and Francis E. Clark, afterwards so notable as the founder and president of the World's Christian Endeavor Society. "1 here may have been others but their names I do not know. Accordingly Thayer invited some members of the class of 1874 to join them, and myself among others. The list of names of the editors published in The Aegis issued the following autumn does not include that of W. W. Morrill. He and I were roommates for three years and I well remember that he was invited to become one of the editors of the paper at the same time as myself. The omission of his name did an injustice because of the great amount and character of the work he did. He was perhaps the wittiest member of his class and an excellent writer, and along with serious matter he would frequently contribute funny articles after the style of the Danbury News man, who was then very much in vogue, and with such success that we thought Morrill had him beaten at his own game. One of the early numbers contained the announcement that Davis '74 was business manager with the laudatory comment that to him "Money may safely be paid." The paper was increased in size from eight to sixteen pages and was said to be the largest weekly then published in any American college. It was not designed to be merely a college journal but along with a comprehensive assortment of news of the colleges and of Dartmouth in particular, it aimed to give a discussion of the general happenings of the day and the interpretation put upon them by college students. In order to increase its constituency it also gave news from some of the surrounding towns. The result was that the paper had the college tang in all its parts and it won the enconium or criticism implied in being termed by one of its city contemporaries "that very college journal The Anvil." Possibly a better and certainly a more vivid idea of the paper can be conveyed by some desultory quotations from it than by generalization.

Professor John King Lord, then as ever one of the most popular members of the faculty and a superb teacher, was married in Washington in the month of The Anvil's birth. The paper anticipated the event by the announcement that "Professor J. K. Lord has gone to Washington on business." To the young lady whose coming in midwinter from a comparatively mild climate to this region of snows and to Professor Lord himself The Anvil in its poetical column extended a greeting in these lines, which I think are by no means ungraceful:

TO J. K. L.

Thou who dost proudly boast descent From worthy sires of a noble race, To that fair home to which a Putnam

lent A holy brightness, and a Packard grace, We welcome thee. And she who with thee braved the storm, And comes to us in this drear winter time, Shall soon forget in our true greetings warm, The coldness of our bitter northern clime, And welcome be.

On the week following Professor Lord's return appeared this item, "The last hymn sung Sabbath morning began 'Joy to the world, the Lord is come. Let earth receive her King'."

The paper was somewhat prolific in poetry. Soon afterwards appeared some verses to Professor J. C. Proctor, a most accomplished Greek scholar, who was passing a vacation in Germany, probably for study or for his health:

"Ye northern breezes sweeping On frozen plains along Waft from your icy keeping Across the seas our song. To where 'mid green grass springing, Neath suns that brighter shine In groves where birds are singing, He wanders by the Rhine.

Oh land through all the ages A mine of golden thought, For history's grandest pages Are with thy genius fraught, Send back with treasure laden From out thy learning's stores With health from Baden-Baden The scholar to our shores."

Occasionally the poet would venture upon an inspiring theme and would produce more than one hundred lines and again he would stoop to depict the most hum-drum working of the academic mill, as for instance:

"Seniors aspiring to whiskers The stage at commencement to crown, Sophomores meek as old Moses Learn to decline the Dutch noun, Juniors take notes on the home school Busy preparing for x, Freshmen in solemn class meeting Decide on impeaching the Prex."

The reading of the files of The Anvil will make it clear that then as now, the "student body"—awesome and venerable phrase—was divided into three parts, the freshmen, the upperclassmen and the superclassmen—the sophomores. The paper contained a department for book reviews and it gave well considered estimates of the leading books as they came out and sometimes of books whose appearance is yet awaited. Of the latter class was the review of "A History of Hanover from the creation down to the present time with notes and appendix V vols. 4 mo. 2038 pp. Hanover Publishing Company 1872."

The review was illuminated with footnotes. For the statement in the text that "Hanover is situated between Mink Brook and the White Mountains," this authority is cited in a note, "Jevenus Torquatus Merrikus in 'De Sophomorico Bello' B.C. 2000 says, 'Hanoverus inter Minkum fluminum albosque montes, conditus nam ibi magnus campus est et limus horribilis et elmi arbores magnifici, nix altissima, frigus permanixum, wood-pili multi et tin-horni permulti fuerunt." Resuming the narrative it appears that the author does not give full credit to the legend that "a most beautiful maiden once dwelt within the town." A footnote is again resorted to for authority. "Ferunt, formosam puellam ibi vivere jam pridem, dubium est." The reviewer then proceeds: "The college was founded at a remote period; of this there is abundant internal evidence." A dispute in regard to its founder is summarily treated by Torquatus: "Dissenio est utrum Platone an Plutone conditus est. Non est dubium quin a Plutone." Even at that early day the officers of the institution held their present positions and names; "Tutores vitae pestes in facultate sunt; Graecus, Mathematicus et Latin—cus."

The editorials were serious discussions of public questions. They were chiefly the work of Thayer and their ability was widely recognized. They were usually long, sometimes equal to a column and a half or two columns in the newspaper of today and had a tone of lofty independence. The editorials upon the Credit Mobilier which appeared in the earliest numbers were notable and attracted attention, not merely from their ability but from the close relation of one of the senators involved, to Hanover, and to the College. No abler or more scholarly man ever went from New Hampshire to the National Senate than James W. Patterson. He was a graduate of the College and had long been upon its faculty. With the exception of Wendell Phillips, I never heard his superior as a speaker. The Anvil said of him, "As an orator he is known on the Pacific Coast as well as here; as a scholar he is widely recognized; and his public life has exhibited a breadth of culture and clearness of thought that have promised for him greater renown than is open to most legislators." At the beginning of the affair The Anvil stoutly and effectively defended Senator Patterson, and under the circumstances maintained that he had committed no offense in the purchase of the stock, but with the appearance of the so-called "Morrill report" and especially its finding that he had testified falsely he fell under the grave censure of The Anvil. It did not, however, at that time have the advantage of Patterson's answer to the Morrill report, a report which he demonstrated to be full of exeggerations and misstatements and which constituted a very virtuous gesture. And reading Patterson's reply it is at least as easy to believe that he had forgotten the details of a transaction five years old as that he had deliberately lied about it.

In, the general attitude of its editorials the paper continued sternly independent and it illustrated in practice its remarkable editorial upon independent journalism, by its support of high ideals and its refusal to confuse independence with mere fault-finding. In fact, it was independent enough even to defend General Butler against some of the attitudes taken against him in Republican conventions in Massachusetts.

The paper had a very complete department of college news and it did not neglect "the jokes that are the characteristic product of college life. It also had a column of questions from correspondents and the answers to them. Of the latter the following may serve as examples:

"Astronomer—You have been sadly misinformed. No member of this college has ever become insane through futile attempts to tie the great dipper to the tail of Ursa Minor with the Equinoctial line just to see the bear jump."

"Poet '76—Our terms for the insertion of original poetry are exactly double those of ordinary advertisements. Payment invariably in advance. Punched railroad tickets taken only at a discount."

There was at the time an option between Greek and Calculus. This and perhaps one other was the extent of the elective system in the College. The Anvil illustrated the working of the system as follows:

"Professor—R, what is the object of studying Calculus?"

"R—To get rid of Greek, sir."

"Port" Rogers used to collect the washing of the students on Sunday. On his eightieth birthday The Anvil records this conversation with him:

"Q.—What will become of you for collecting washing on Sunday?"

" 'Port'—Go to the bad place, I suppose."

"Q.—But what do you expect to do there ?"

" 'Port'—Just the same as here—wash for students."

The paper covered events of importance taking place in New Hampshire and sometimes in Massachusetts; for example the inauguration of the governor and a women's-rights convention at Lancaster. It is not necessary to say that these reports were not entirely serious. For instance, in the report of the inauguration of the governor appeared the statement that His Excellency arose and announced in a firm tone that he had a sore throat and that the clerk would read his message. And again "The inevitable Conant Hall (now Hallgarten) and that large junior class expected next year in the Agricultural department found a place in the message." And again "The Crowded hall remained silent, especially the members, a large quorum of whom slept very peacefully throughout." The same style of reporting would inevitably be found in the account of the women's rights convention. Indeed, some of the ladies who were leaders in the movement wrote a letter to the editor declaring that when they saw the look of veneration "that passed over the face of your youthful reporter" they expected more serious treatment. But to one reading the report today it would seem wholly good-natured and most parts of it complimentary.

The paper was, for the times, very enterprising. The college boating convention was held that year in Worcester. Worthen of '73 and myself were delegate's. The paper could not of course stand the expense of a long press dispatch, but Thayer and myself devised a cipher under which at trifling cost TheAnvil was able to print the next morning the material results of the convention. That was the first year in which Dartmouth took part in boating and it was far the overshadowing athletic interest there and indeed among all the colleges. There were ten colleges in the association and Dartmouth and Columbia were applying for admission. There were rumors that we would not be admitted or if admitted would not be permitted to vote, and it was necessary to do some political canvassing. We found a staunch friend in "Bob" Cook, then near the beginning of his long boating career at Yale. He was a man of few words, had the appearance of General Grant, and what he said one could rely on. We were admitted without much difficulty. But an excited contest took place over the qualifications to membership upon the crews. It was finally voted to limit the membership to those who were studying for the ordinary undergraduate degrees. This was obnoxious to Harvard, and its paper, The Magenta, the predecessor of TheCrimson, indulged in a not very goodtempered criticism of the action of the convention, which the Harvard delegates had opposed. The Magenta claimed that she had appeared as the defender of the rights , "of the smaller colleges" and set up the claim that she should be permitted to put upon her crew men from her medical, law and divinity schools. Worthen replied to this article in a communication to The Anvil, in which he sarcastically directed attention to the consistency of Harvard in opposing the efforts "of the smaller colleges" to have upon their crews men following the same studies as were under the optional system at Harvard included in her academic department, and failing in that of claiming the right "to recruit her crews from the broad fields of her numerous professional schools, in which she is practically, without a rival."

It was decided that The Anvil should issue a daily during commencement week. So far as I am able to learn, this was the first daily published in any American college. The New York Independent spoke of it as "the last enterprising feature of college journalism" and expressed the hope that this "largest of the undergraduate weeklies" might in its commencement daily be the "forerunner of a new thing in the already promising field of college journalism." It is noteworthy that not merely at Dartmouth but at numerous other colleges the college daily is now an established institution. Perhaps it would be in place here to refer to some of the references to The Anvil contained in other papers. The New York World said the " 'boys' of Dartmouth College deserve great credit for founding and editing with good judgment and much brightness The Anvil." The Boston Traveler spoke of it as a "very able paper, strong in its likes and dislikes but always courteous." The Boston Transcript said it was "sparkling, independent and creditable in every way." The Fort WayneGazette hazarded the opinion that it was "one of the brightest papers we have ever seen. ... It exhibits a thoughtfulness and ability that would do credit to a metropolitan journal."

But what was to be done with TheAnvil during the long college vacation? Thayer thought that its publication should be kept going, and with the intention of continuing the paper as a steady enterprise, and to enlarge its somewhat narrow constituency, he established an agricultural department to make an appeal to the many possible readers in the vicinity, and he secured the services of a noted agricultural writer. Thayer's health weakened under the strain and returning to Hanover, as I did shortly after the beginning of the vacation, I lent a hand and helped fill up the editorial columns of the next issue so that it appeared on time. During the following summer I sent contributions from my home, and I think other absent members of the board of editors did the same thing.

There was a fierce contest at the regatta at Springfield, in which The Anvil took a keen interest. Thayer was president of the boat club and I, the vice-president, but his work kept him at Hanover and I went to Springfield to look after the crew. I was also the Dartmouth judge. The race took place late in the afternoon and there was a mist hanging over the river, almost amounting to a fog. Each college had a judge at the finish line. We stood upon a float to get the order in which the crews crossed the line. Upon the opposite side of the river came the Harvard crew, which followed the bend of the river and crossed a line at right angles to its banks. But very near us upon our side two crews sprang out of the fog, their boats lapping, and crossed the line parallel with the starting line and which had been fixed upon as the finish line of the course. The two crews were Yale and Wesleyan, in that order. At once a fiery controversy arose. The claim was made that Harvard had won the race and it was the subject of magazine articles, and of no end of communications in the newspapers. The referee decided and so far as I know, that was the opinion of nearly all the judges that the race had been won by Yale. No other conclusion seemed possible because the finish line parallel to the starting line had been fixed beforehand and aside from that there would have been no justice in permitting a crew with the inside track to follow the bend of the river and be awarded the race because it had crossed a line at right angles to the banks when it had probably rowed by a hundred yards a shorter distance than had the crew upon the farther side. The Anvil in its editorial strongly supported the claim of Yale and the decision of the referee, and characterized in strong terms the attitude of Harvard. It declared "of all ridiculous things the attempt to show that the goal line should have been drawn at right angles to the river's course seems to us the most of all."

During the summer Thayer received a flattering offer from the New YorkTribune. It was becoming apparent that the paper could be made to pay only with great difficulty and he had taken upon himself a very heavy burden of work. He finally decided to go upon the Tribune and soon became its night editor. From there he shortly went to the Times, where he became the assistant managing editor.

I remember once when I called upon him of seeing Miller of '72, who had come from the Springfield, Republican. It may have been simply an inference on my part, but I had the impression that it was through Thayer that he first found a place upon the paper. Thayer would have made a great journalist. He decided, however, to enter the ministry and went from the Times to Andover, where he graduated. After a brief period in the ministry he died. He was a man of rare dignity of character, of fine talent and of the highest ideals.

When Thayer left the paper he settled up with the printer, and those of us who were left decided to continue its publication—although with a good deal of doubt on account of the discrepancy between its revenues and its expenses. We added to the number of editors, taking more men from our own class and also some from the two lower classes. In addition to those mentioned above, there appear in The Aegis issued at that time, the names of Brainard, Taylor, Powers, Aiken, Lee, and Parsons of the class of '74, and Wiggin, Foster and Sayres from the junior and sophomore classes. The paper continued to run upon the lines on which it had been established. But the steadily growing debt led us to hold a council of war with each other and with the printer, "Old Whit," as we affectionately called him, and although our credit with him was still good, we decided to pay up and stop publication. Each man gave his note for his share of the debt, and I believe every note was afterward paid with interest. In some cases, however, the principal of the debt was of small importance compared with the interest for at that time they had a way of reckoning interest in New Hampshire which made compound interest seem mild.

In one instance the paper came in sharp collision with the authorities. Under the heading "About Town" there appeared among a series of more or less nonsensical items the following:

"The Hanover Bank has suspended payment—cause want of the ready. The suspension is only temporary."

The Treasurer of the College was the cashier of the bank and as collector of tuition fees the writer apparently regarded him as fair game, but it was a trifle audacious to publish such an item when the country was in the throes of the panic of '73. The fact was that the chief editor was away and probably never saw the item before it was published. Stern discipline was threatened and finally a retraction was agreed upon; and in the leading article of the next issue of the paper the bank was made the object of an enconium, decorated with classical allusions such as no other bank has ever received. It is worthy to be reproduced here as an example of that sort of writing:

"RETRACTION"

"By an inadvertence in our last issue we did injustice to our bank. Fortunately few read it and none believed it. Those acquainted with the status of the bank and the integrity of its officers, at once saw that it was an error. We hasten to make amend, for of our bank we have always been proud. While other institutions appearing as well in the Comptroller's ' Report were tumbling with alarming frequency, our own stood like Ajax and defied the lightning, at once vindicating the prudence of its direction and the soundness of the national system, which our own Chase founded. In its new banking house convenient to the citizens and an ornament to the town, we feel sure that naught can harm it, save the act of God or the King's enemies, the only two contingencies the common law could not provide against. And as we think of its management judicious, sagacious, and courteous, we say as Jefferson did of the Constitution.: Esto perpetua, or in the statlier Latin, slightly altered, of the bard of Mantua: Semper honos nomenque tuum nummosquc manebunt"

The connection with The Anvil seemed to bring to most of its editors luck. Each one of them afterwards turned out well, and some of them very well. A couple of chief justices, members of Congress, four or more trustees of Dartmouth and other colleges, writers of notable books, well known editors and highly successful lawyers and doctors, with distinguished preachers may be found upon the list. It was a group to which it was an honor to belong and service upon which was a. very real pleasure. But that satisfaction was merged in the wider satisfaction which came from membership in the larger groups of class and college. At that time the Dartmouth students came in the far greater proportion from the four northern New England states and were almost wholly of the stock that settled and built up those commonwealths. As one of the comparatively few who found their way into the College from distant states and who would not be included in this observation, I may express the opinion that neither Dartmouth nor any other college will ever be fed by a sturdier stock. The striking qualities of the men were manliness and independence. Under the influence of association with each other and with the faculty of that period, inspired by the golden air of the place and the witchery of its surroundings as well as by the traditions of the College the students were animated by an intense patriotism. To them Dartmouth was unquestionably first; and the feeling of kinship that one has in looking back upon a close college comrade of that remote time brings to mind the words which Orestes spoke to Pylades: "Oh boy that played with me and hunted on Greek hills."

A Specimen Page of The Anvil

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe action of the Board of Trustees in electing Doctor John M. Gile '87

March 1923 -

Article

ArticleTHE ORIGINS OF DELTA ALPHA—A SYMPOSIUM

March 1923 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March 1923 By WILBUR M. URBAN -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

March 1923 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

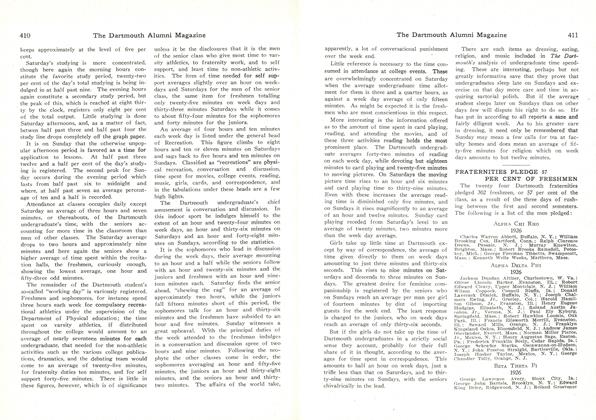

Article

ArticleFRATERNITIES PLEDGE 57 PER CENT OF FRESHMEN

March 1923 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH ANALYZES COLLEGE'S USE OF TIME

March 1923