from which to draw conclusions concerning the necessary alterations of the college curriculum seems to have reached the point at which intelligent consideration may begin. There is on file with the administration a long and thoughtful treatise on this matter from the undergraduate committee of last year, and to this is about to be added the compiled report of Professor L. B. Richardson, Who has been delegated to make a personal survey of university and college methods both in this country and in the British Isles, of which at least an outline hds already been given by its author. In short the spade-work has been done which had to be done before much beyond idle theorizing could be expected. We are on the point of taking up the problem in serious earnest, with intent to discover what—if anything—is amiss with our methods.

It should be understood, we believe, that this is not a parochial or provincial matter. Eager inquiries from other colleges in all parts of the country concerning what Dartmouth's investigators have discovered indicate that the feeling of dissatisfaction with academic systems is universal. The reception accorded Professor Richardson everywhere is evidence that the other colleges have experienced similar questionings and greatly appreciate the fact that Dartmouth's investigation tends to bring discussion to a head. A polite wonder has been expressed in some quarters that this has not been taken up in this way before plus a polite wonder that it happened to be Dartmouth which initiated the movement.

It remains a possibility that the conclusions finally reached will be negative —that is, will bear out the contention that all things considered the problem is already being dealt with in as satisfactory a manner as conditions peculiar to America allow. That is a possibility, however, rather than a probability. Advance guessing is rash in such a case; but we should say at the present showing that the more we investigate this business, the less we shall find to be essential in the way of radical amendment. The changes will probably b£ in the line of intensifications here and moderations there, rather than changes of a far-reaching and upsetting sort. Things that have been overdone will doubtless require to be minimized and things that have been underdone will need to be exalted beyond their present estate. But that a wholesale revising of the collegiate system impends, we find ourselves unready to believe.

As has been intimated several times before, we incline to regard as of the very first importance a clarifying of the issue by a definition of the aims of an American college. To that end it seems that the definition set forth by the undergraduate committee last spring will be hard to beat. It was by far the best thing in the undergraduate report and it went a very long way toward solving the problem itself. It is apparent, however, that what Professor Richardson has done in his months of travel and study of the situation is sure to amplify the discus- sion of details and bring it down to what it is fashionable in political circles to call "brass tacks."

It remains a fact, in our judgment, that the first and great commandment is to establish precisely what a college is trying to and-and then proceed to a discussion of ways and means for doing it. If we have any criticism to offer concerning the elaborate suggestions of the undergraduate report on the detailed matter of the curriculum, it must be that the desire was greater to get at once to the business of living with current problems of life than it was to seek preparatory measures looking toward that end. The embryo artist is usually impatient of fundamentals. There's small excitement in running scales. One craves to be given a "piece" to play—something rather lively and pyrotechnic. Training is dull stuff—it is what we believe our present college vernacular calls "drip." The lower terraces of the Gradus ad Parnassum are uninspiring. One longs for the view from the loftier levels.

The vernacular is a very picturesque instrument of expression and one which editors of dignified publications like this should hesitate to employ; but we cannot forbear the remark that the outgivings of various investigators seem to stress the idea that the motto of every progressive institution of learning might well be "Use your bean," rather than "Vox Clamantis in Deserto" or "Christo at Ecclesiae." What to do in order to make young minds into facile instruments of usefulness ? How to combine preparation for special activities with the provision of a general background? Just what is a "liberal education?"

The answers to all these questions must be left to the unprejudiced consideration of those most competent to decide. The MAGAZINE, while it has vague ideas of its own, has no intention of exaggerating theif value or of putting them forward with sophomoric assurance prior to the discussion of the matter by men vastly better qualified than are its editors to know what conditions require.

It may, however, be appropriate to suggest one or two things which it is understood are also recognized in the preliminary survey made by Professor Richardson. We have to remember all the time that we are dealing with human beings rather than with things. We have to take account of certain peculiarities in our national situation. We must, if we are wise, allow for the persistence of some elements, such as athletics and fraternity life, which are so far an integral part of American college existence as to make their elimination for the sake of attaining a theoretic perfection virtually impossible. It is not at present possible for us to conceive of a remodeled college in which there should be no such thing as fraternity life, and no such thing as intercollegiate sport.

The two things are notoriously antagonistic to the purely intellectual activity of a college—but they are very far from being without merits of their own. Man floes not live by books alone, any more than he lives exclusively by bread. It is unquestioned that a necessity exists for bringing these antagonistic elements into their proper relationship to the academic picture—but one may as well dismiss at once as fantastic any suggestion that they cease entirely to be. It is this fact, as well as the various facts relating to the rearrangement of major and minor courses, that makes us slow to expect very radical changes as the result of this current and highly stimulating investigation.

The athletic question is naturally acute after a season in which the football schedule has been so comprehensive and so provocative .of a feverish interest. With all our relish for a glorious season of sport, we are quite frank to say that it obviously militates against the academic work of the college and unsettles the routine (which is the college's real excuse for being) to a degree surpassing the tolerable. When Saturday after Saturday brings its "big game" and its temptations toward wholesale absence from Hanover, as well as toward an unsettling state of mind for all concerned —not by an means excluding the professors from the category—it seems hard to avoid the conclusion that it is overdone and needs toning down. How much? In what way? That is an administrative problem, with which it strikes us as impolitic to meddle; but we find ourselves compelled to the conclusion that to some extent and in some way it needs toning. It isn't fair to the college to make quite so much of intercollegiate athletics as we have done this fall. We have all enjoyed what the athletic council very properly calls an "ideal" schedule but it really has not been an ideal schedule from any but the sporting standpoint. It has been rather too highly spiced for human nature's annual food, unless we stand ready to admit hat sport comes first and is our real raison d'etre as a scholastic institution. If it affected none but the men on the. squads it would be more defensible, but the fact is it affects the whole college, from top to bottom, almost as vitally as it affects the players themselves. With all our liking for the general custom of intercollegiate contests, it is our conviction that we should do better to limit their extent somewhat more straitly than we have done this autumn. A high spot in our athletic history it may have been but the price one has to pay for it seems to us too great. This is one of the things that probably needs to be toned down to its appropriate phase as a component part—a very necessary component, too—in the picture of our college living.

With the growth in importance of the Alumni Council as the effective organization of the alumni body comes the corresponding necessity for the insurance of a proper recruiting of this representative organization from year to year. The present size of the alumni fellowship inexorably precludes the doing of much business on the town-meeting principle and this fact has been recognized more and more in recent years—as witness the final abandonment of -the old custom of electing alumni trustees by general vote. Circumstances force the alumni to representative government, and repiesenta tive government requires adequacy of the representatives. Observation of the Council in actual operation leads to the gratifying belief that it is ordinarily and certainly at present—a thoroughly wise and trustworthy body of men, in whose hands alumni interests are uncommonly safe. The word we would add to this relates only to the imperative requirement of keeping it so, by adding to its personnel, as the various terms elapse, men equally reliable both of ability and for attendance upon the meetings. That there be rotation in member- ship we believe to be exceedingly desirable, to the end that there may be avoided that crystallization into a sort of established hierarchy which besets every alumni body with such deplorable ease.

Meantime it is a practical way of serving the college which should be inspiring to every loyal graduate. The element which relates to attendance upon the meetings naturally affects most vitally those regional alumni bodies which lie at a distance from Boston, Hanover or New York, where the meetings are more commonly held for the greatest convenience of the greatest number of dele- gates. But the functions of this body continue so steadily to increase in both number and importance that we feel the power to be present and to take an active part is one of the essential things which must be taken into consideration in making choices. The recent alteration of the method for choosing alumni trustees intensifies this requirement and puts up to the Council itself the task of insuring its continued efficiency as the servant and representative of something over 6000 scattered graduates, who must rely on its wisdom and on its sustained interest.

There comes to hand a yellow-covered pamphlet announcing itself to be a special supplement to the British publication "Youth," dated a year ago and containing a symposium of sophomoric views, translated from the German, concerning the part which the young are about to play in reforming a world hopelessly debauched by their unimaginative elders. It may be said at starting that these young people take themselves with a seriousness that is disarming. Their one conspicuous lack is anything that savors of self-distrust.

"Youth" appears to be "an International Quarterly of Young Enterprise," and if one may judge by the specimen now in hand it is parlously maintained by the '"lntellectuals" of various countries. Those in search of mouth-filling language will find it rewarding. The opening page contains a moving appeal for money. We note that the finance committee rejoices in the name of "Hilfsausschuss fur. Werkgemeinschaften der Jugendbewegung." There follows a choice assortment of articles by immature malcontents, pacifists, socialists, psychoanalysts and so forth—all Germans, save one who indites an introduction to the English edition, and an- other who megaphones to the world "Why Young America Looks to Young Europe." The latter appears to be John Rothschild, who sees hope for the future only in the European students, because "They make an irresistable (sic) appeal to our longing for a life which has meaning." Mr. Rothschild is thus made to appear rather anarchical even toward the accepted conventions of English spelling although conceivably this is due to a misprint.

Time, space and especially language fail to enable a detailed consideration here of this amazing hash—but it is of the old familiar kind. It represents the demand of headlong youth that the elders resign the helm and permit enthusiastic lads to steer. There is notoriously little virtue in age, and a perfectly prodigious virtue in inexperience. Youth will be served. It is much pleasanter to know how to spell fascinating words like Jugendbewegung than it is to bother with humdrum "able" and "ible" terminations. One may look for quintessential wisdom from youngsters with names like Seich- wein, Klatt, Schlichting, Oestreich, Haffenrichter and Kawerau, much more surely than to Smith, Jones and Brown. Contributions of money must flow more readily toward a. yawning Hilfsausschung fur Werkgemeinschaften der Jugendbewegung than toward a mere committee on finance.

Just how much of this balderdash can healthy-minded young British and American college boys manage to swallow, before an instinctive regurgitation supervenes? More than one likes to believe, perhaps—but by no means so much as the hopeful crusaders of Jugendbewegung suppose.

As an antidote we now find appended to the pamphlet (why the yellow cover, by the way, when there's plenty of red left in the world?) a clipping from the Manchester Guardian's weekly edition, which rather sits on the bumptious assertions of these enlighteners of mankind. The Guardian, itself somewhat given to hospitality toward new ideas, at- tributes this volunteer lecturing by the young to a sentimentality growing out of the war. This, it affirms, "was a kind of mock-humble appeal to youth to take over and run in some new and better way of its own the world of which its elders had made such a mess before and during the war. Youth had then been having long lists of casualties for four years and a quarter, because it happened to have more qualifications than middle or old age for the branches of war work which lead to extinction. So everybody was sorry for youth; and in sentimental minds this sympathy often expressed itself in a vague idealisation of so many of our young men as were left, and even of their undecimated female contemporaries. Gushing people told youth, to its face, that it had come into a kind of Messianic mission and that we all looked to it to save us from our sins, or at leasts from their disagreeable daily consequences. Probably youth, so far* as it was sensible and free from vanity, laughed at this rubbish. But, where this angelic guardianship failed, it must often have snuffed up the myrrh, and frankincense without demur and perhaps thought there might be something in the new doctrine of the divine wisdom of inexperience—it always did take a rather uncommon young man or woman to believe that experience had still much to teach."

This is spoken of here chiefly because of the growing restiveness of older alumni in American college circles against the seeming spread of boyish radicalism. For the reassurance of such, note that in his turgid periods Mr. Rothschild seems pessimistic of American college youths. "Last spring," he wails, I travelled extensively east of the Mississippi and saw America through a microscope. I found many problems; yet in the 25 colleges which I visited there was only a handful who would face them with me!" This sentence seems rather a mixture of singulars and plurals, but Mr. Rothschild is manifestly writing under stress of emotional excitation. What he says, in effect, is that he found himself a voxclamantis in deserto—a deserto of dull American bourgeoisie. "Only a handful" of students anywhere would listen to him when he began expounding the gospel of divine discontent with everything that now is. There is no hope in America. The true light must come from Europe —preferably Central Europe, where the people have such interesting names and where the fragrant Hilfsausschung fur Werkgemeinschaften flourishes so luxuriantly among other exotic flora and fauna.

Meantime a feeble beam of this new dawn filters to us through a touring band of evangelists, who have included Dartmouth in their itinerary. These young men, "ranging in age from 21 to 28," we are informed constitute "an Embassy of Youth." Their roster is resonant with the trumpet call of hope. Karl J.A.C. Friedrich, Jorgen Hoick, Antonin Palecek, Hans Tiesler and Piet Roest are teaching American boys what's what— humbly assisted by a certain Professor Robson of the University of London, who has a name that looks rather odd in that galley, but who is doubtless ready to prove the doctrine orthodox even from the unimaginative standpoint of bourgeois Britain. "It is possible that here, as in Europe," says Mr. Rothschild, "young eyes will be the clearest for viewing critically and the strongest for scanning the future." Even so! And young tongues the loudest for telling the world!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE DIARY OF MRS. PRESIDENT BROWN ON A JOURNEY TO THE SOUTH IN 1819

December 1924 By John K. Lord '68 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

December 1924 By H. Clifford Bean -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

December 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Article

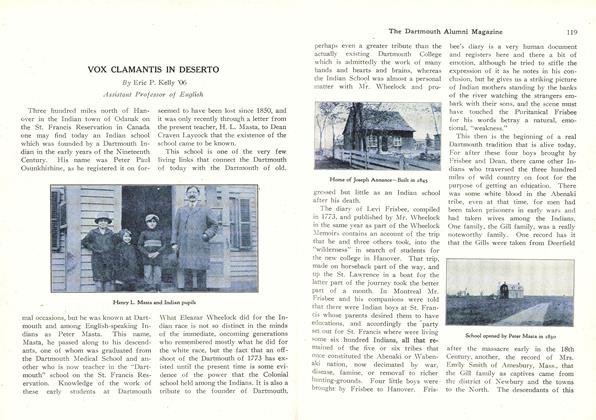

ArticleVOX CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO

December 1924 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksFrances Wright.

December 1924 By W. E. S.

Article

-

Article

ArticleTRUSTEE MEETING

JULY 1931 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

-

Article

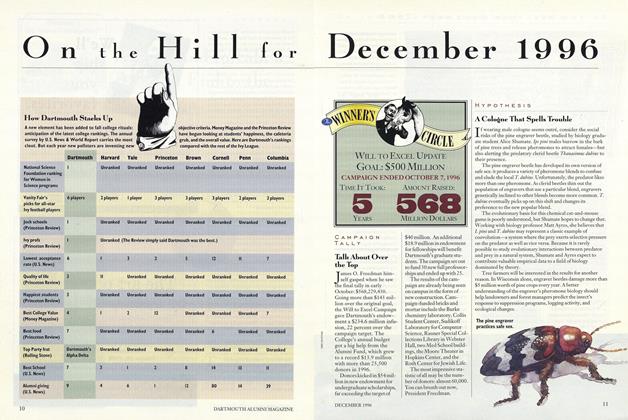

ArticleA Cologne That Spells Trouble

DECEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleDial M for Mogul

November 1975 By D.M.S. -

Article

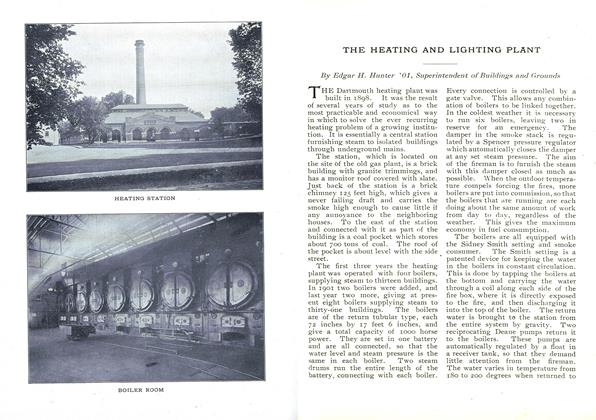

ArticleTHE HEATING AND LIGHTING PLANT

FEBRUARY 1906 By Edgar H. Hunter '01 -

Article

ArticleTHE MAY CONFERENCE OF HISTORY TEACHERS

June, 1911 By Sidney B. Fay