It makes a good story to tell that the president of Dartmouth College said that he would bring in Lenin or Trotzky as instructors if they were available—especially as he said it in retort to a disgruntled objector to one of the faculty members he did bring in.

As a good story it gets blazoned on front pages of newspapers, but out of all proportion to the much better one of what he went on to say:

"I know of no man and no interest I would not present if it would stir up the mind of the undergraduate . . . Open-mindedness and the ability to think are, I believe, among the most cherished aims of the liberal college, and the greatest need of the hour." This is not the ordinary language of ordinary college presidents. It betokens a man who has been down cellar with lantern and hammer rapping the foundation walls of our national mentality to see whether they were solid, and has found a hollow sound. That hollow spot is—to put it politely—intellectual timidity. We are afraid of ideas. Suggest to us that the drama of human evolution did not come to a triumphant close in 1789, the year the Constitution of the United States (since amended 19 times) was adopted, and we are likely to be alarmed and resentful.

The hypersensitiveness of public emotion is reflected in our colleges. The new graduate schools of hotel management and commercial efficiency with which they are rapidly lumbering up are immensely popular. But suppose a professor sets me to examining and perhaps questioning the worth-whileness of my inherited ideas of government, economics, morals, customs and social institutions? What is the good of that? Is it any good? Isn't it, on the contrary, bad ? Shouldn't we take such things for granted and not question them at all?

I asked a young Englishman who had studied at both universities to tell me the difference between Oxford and Harvard. He looked embarrassed and said, "You Americans are always asking questions like that," but finally brought out:

"In Harvard we say of a good student, 'He knows a lot.' In Oxford we say of such a man, 'He knows how to use his head.' "

We in America are prone to think of education as the acquiring of some practical knowledge which will sell. The other conception of an educated man is as one who has learned to use his mind for independent and creative thinking.

Suppose I spend four years packing your skull full of facts about the history, art, literature, religion, government, philosophy and science of the European races for the last 2500 years, till you know them like the palm of your hand. Suppose, also, that I never suggest to you that you should use these facts as •the basis of study and comparison to call into question every idea and institution of the land and time in which you live. Suppose that if I did, you would be suspicious and think me "queer", possibly even dangerous; or, if you did not, that your elders would. And suppose we lived in a period when, whether we liked or no, all these ideas and institutions were being questioned, if not by the educated classes, then by others; and that great numbers of supposedly educated people were excitedly demanding that this questioning be stopped. What would be the value of an "educated" man, so educated?

To pour quantities of fact-information into the minds of youth without setting them into independent motion on that material is like hanging a chart of physical exercises on one's chamber wall and expecting to develop muscle by sitting still and looking at it so many hours a day.

The only way that life can advance is by the young taking the ideas and institutions inherited from their elders, turning them inside out, understanding them, and then proceeding to create for themselves. This act of intellectual creation is the supreme function and glory of our human kind. It can be exercised in any trade or profession, from the humblest to the highest. But it grows nobler and more powerful as it gets into the immaterial realms of conduct and thought. To those who know this power and learn to use it, all the other prizes of life are seen to be secondary: money, position, career, even romantic attachments. And a college which could, each year, set the feet of even a few young people on this mountain path would be doing more for its country than myrmidon battalions of technical experts proficient in the practical administration of this or that. For technical experts are, necessary though they may be, in the long run only the pick and shovel men of the thinker. Behind and above all others, the independent and creative thinker, rough as may be his path, dominates his age, and all ages.

And so when a college president, and a measurably young one, declares for this side of the game, it is immensely inspiriting. For we in America have come to the forks of the road, where a momentous choice must be made. Our pioneering is done. Our continent is wellnigh subdued. And here, at the end of the triumphant achievement of that physical task, we must decide whether, for lack of originality and imagination, we shall go on trying to subdue other physical continents and get into trouble trying it; or whether we shall have the will and the intelligence to turn gladly now to the cultivation of our own finer powers the powers of mind, of social readjustments, of cultural and spiritual life.

We have developed a continent. Now can we develop ourselves?

Another pleasing reaction was that of TheOhio State Journal, Columbus, Ohio, which wrote as follows:

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE POW WOW

April 1924 By E. Russell Palmer '10 -

Article

ArticleIS THE COLLEGE EDUCATIONAL PROCESS ADEQUATE FOR OUR MODERN WORLD?

April 1924 By Charles Dubots '91 -

Article

ArticleThe Chicago Pow Wow which

April 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

April 1924 By H. Clifford Bean -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth

Article

-

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES HOLD SPRING MEETING

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNIVERSITY CLUB RANDOLPH, VERMONT

June 1941 -

Article

ArticleThe College

APRIL 1971 -

Article

ArticleMaking the Grade

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleMid-Hudson

FEBRUARY 1969 By JOHN M. COULTER '58 -

Article

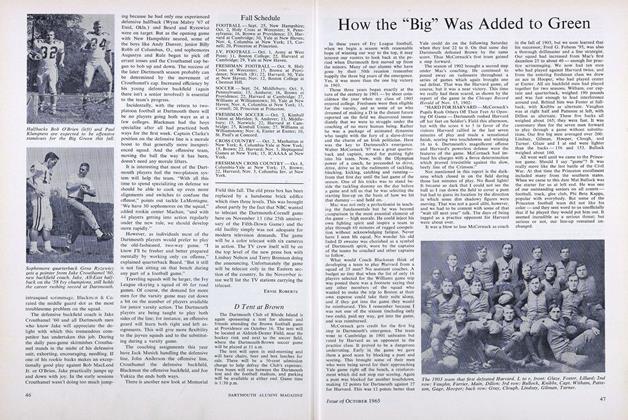

ArticleHow the "Big" Was Added to Green

OCTOBER 1965 By W. HUSTON LILLARD '05