IS THE COLLEGE EDUCATIONAL PROCESS ADEQUATE FOR OUR MODERN WORLD?

April 1924 Charles Dubots '91An Address delivered at the First National Pow-Wow of the Alumni of Dartmouth College held in Chicago February 22-23, 1924

Last summer the Alumni chose me as one of their representatives on the Board of Trustees. This is the first opportunity I have since had to appear in person before any considerable number of them and to express as I now do my appreciation of the honor and my acceptance of the responsibility.

One of my first duties as a trustee so it seems to me—should be to try to think out from my own standpoint, that of a middle-aged observer, an industrialist, not an educator, what the purpose, the objective of the College realty is and what the College ought to be doing particularly in its educational policies toward that objective. There are many points of view from which education may be considered and criticized. A composite of such viewpoints would probably be close to the truth. My own viewpoint is but one of many and I submit it with diffidence, first stating with emphasis that I am not presuming to speak for the Board or an}' other member of it.

I take it that the objective of Dartmouth College to-day is to give to a rather carefully selected groups of boys such an environment and training for four years as will best develop their powers for useful lives.

We must assume, I think, that the College will continuously be judged by the quality of its graduates and in the long-run by this test alone.

It is the duty of the trustees, as I believe, to see to it that this general objective is striven for with all the resources they can command. And the most important thing they have to do is to see that the Presidency of the College is entrusted to the right man and then to back that man to the limit. In the history of Dartmouth College this has not always happened. In its most notable administrations, two of which are familiar to us all, this has happened and the results have been hardly short of marvellous. I refer of course in the first instance to Dr. Tucker, whose genius and devotion made Dartmouth a modern and national institution, and I refer in the second instance to Dr. Hopkins, the present head of the College, whose fitness for the great responsibility he bears is so conspicuous not only to partial Dartmouth eyes but to the whole nation that the words of laudation I might say—but will not because he is present—would at best seem superfluous. These two eminent men have gained and held in a notable degree the confidence, affection, support and respect of alumni, undergraduates, faculty and trustees alike. It is a privilege to act as a trustee while the College has such leadership.

And yet to take it the trustees do not and can not abrogate their proper functions however competent the President they choose. In troubled seas they with him must collectively seek the course to follow. On a ship there must be only one captain but there must be other fargazing eyes looking for changes even when the sea is calm, for it is not always calm—it ever has its hidden dangers and the course to follow must alter for winds and currents though the port remains the same.

The day-to-day management of a college is beset with difficulties. As Mulvaney said in Kipling's tale of a thrilling adventure "'Tis no easy task to ride a wild elephant". And yet I believe a more puzzling problem is keeping the college objective so vivid that the college product is always corresponding to it, in terms of the future, not the past, not indeed even the present. It is easy enough to say that we plan for the unknown when we plan for the future. Yet in some fundamental requirements the future is not obscure.

One element of our objective as to quality of men who are to graduate stands out as brightly as the evening star. It is the importance of high character. Perhaps it has always been equally true but I see the greatest need of the country and of the world in the years directly ahead of us to be more men of positive high character which insists that the right prevail, as distinguished from the merely negative goodness which refuses to do wrong. Where you find such men to- day in the key positions of a community, an industry, an institution or a government, there you inevitably find a clean and wholesome atmosphere which lifts life for all those concerned above its daily burden of work.

Undoubtedly the fundamental bases of high character go back of the college to the home, the school, the community and to the ancestry. Yet it seems usually (there are exceptions) that character is setting into a stable form between the ages of eighteen and twenty-two and the inspirations, the perplexities and the contacts of college life have an influence on it not to be measured by any human yardstick.

It is a matter of opinion or judgment rather than susceptible of proof by facts, but I have a conviction that American college men today average up to a higher standard of character than they did thirty years ago and that in comparison with the general standard of character in the country the improvement is even greater.

And while there seem to be no limits to possible human progress in character upbuilding it is I believe generally agreed that individual intellectual capacity is not increasing and has not in fact increased in the past two or three thousand years. Prof. Conklin says this in "The Direction of Human Evolution" but he agrees that "society has advanced because it has profited by the experiences of the past". Again he says "The intellectual evolution of the individual has virtually come to an end, but the intellectual evolution of groups of individuals is only at its beginning".

Now the sum total of human knowledge is enormously increased. The accumulated knowledge of only the past thirty years in all scientific subjects especially is prodigious. With the exception of some advanced courses the colleges do not do and cannot do much more today than teach some elementary knowledge of many different varieties—so far has our store of knowledge outstripped our capacity to absorb it. What then are we doing? We are taking young people through a course of instruction in a given limited time about as we might drag them through the Metropolitan Museum in an afternoon, hurrying on from one thing to another so as to cover the whole ground, periodically stopping them for a cross-examination—a few questions selected at random out of many that might be asked. If they answer enough of our questions with some degree of accuracy they pass on—if not, they are scholastically in disgrace.

Just before the recent mid-year examinations an advertisement appeared in The Dartmouth offering tutoring services and promising money back in any case where the man after a review of 5-3/4 hours should flunk his examination "no matter how low his standing before the exam." Information is not available as to results, but the cramming and examination system is brought sharply to task by the pointed comment of TheFreeman which asks why this tutor should not be invited to take over the college job and so cover in a few hours with positive results the ground over which a professor labors for fifteen weeks with uncertain results.

And The Dartmouth commenting on this editorially, with the aptness of youth to catch a situation and with some grim humor, says "We don't know where we're going but we're on our way—and we're proud of it". We need not take this particular case too seriously but it may stimulate thought on the value of examinations as a part of an educational process in considering that process from the standpoint of its usefulness for future lives.

Whatever its other merits may be. I submit that the low-pressure term work, with the high pressure review and examination have no semblance to anything college men will later find in an actual workaday world.

I pass over the problematical mental and physical effects of long periods of slack or intermittent work followed by a few days of extraordinary, sometimes exhausting effort, culminating in a crisis of mental effort on which so much depends. I assume that the experts have studied this and find no serious harm in it. Undoubtedly those survive it who are fit to pass examinations but I would like to be shown how it helps fit them to face any normal or usual scheme of life.

In sober fact does the whole educational process as we know it ending with college provide for an adaptation to the lives that must be lived?

I am ready to grant that it does one thing of some real importance. It opens the doors of many departments of human knowledge and affords a brief glimpse within. This is much for even the average man gets something real by a mere sight of the treasures of knowledge while the intellectually curious will go back to them again and again as the years go by.

Any life should have its philosophy and he who has as a basis for his own philosophy some coordinated and systematized arrangement of such knowledge as he may get is by so much raised above blind dependence on his instincts or the control by others of his thinking.

It may be too that the scheme fits fairly well for post-graduate professional study. But these men who are to study pro- fessions are definitely the minority in our colleges (about 20% at Dartmouth) and thev too must later enter a world which has in it for them much more than their professional activities.

One's life is not merely one's work and an education that really provides for adaptation to life means far more than that vocational or professional training with which the college is not directly or properly concerned.

Look at the problem from another angle. Why should graduation involve as it generally does I think, a complete change in outlook, motives, habits of thought and methods of work beyond what the change in residence, associates and kind of work must involve? Why should it not be a natural transition rather than a violent wrench, a promotion if you like rather than a reversal, and generally a depressing demotion.

Nearly every middle-aged man looks back on his four years of college life with a sentiment of almost ridiculous affection. Much of this is the pathetic wistfulness of age toward those most glorious years of youth. Much of it is related to the associations and friendships then formed. Some of it is the place. Some of it is the memory of participation in sports and other activities, legitimate and otherwise. But how much of what we look back to with such affection is the pleasure of preparing lessons or reciting in class-rooms or wrestling with examinations ?

We are all prone to think we would like to live the college life again and some of us may think we would seriously like to take the course of study again, but I doubt if any of us would want to take it by the method we remember. Was anyone ever an enthusiastic believer in that method either then or since?

There are thousands of young men of college age, but not in college, at work in the world, performing work under far less agreeable conditions than college work and extremely interested in it. And college graduates are keenly interested in their work after they have adjusted themselves to it. But why should adjustment be necessary? Rather, why should not college be the adjustment period? In a different sense college is an adjustment experience—but I submit that an infinitesimal part of that adjustment is due to the college curriculum and teaching.

Youth like Barrie's Sentimental Tommy "finds a way". One of the definite things nearly every man has to do in life is to work co-operatively with other men in such a way that the combined efforts of a group accomplish a result impossible for an individual. Does the college boy get practice in that from his .college work? Only in the slightest degree; but so sure is the instinct of youth that not finding it there he creates it so far as he can for himself, in sports, in publications, in dramatics, in fraternities, in all the manifold group activities and organizations that make up college life apart from college work.

Another requirement life seems to impose on most men is continuous attention to some certain piece of work till it is done; all day perhaps, or several days or even weeks and that job done is followed by another. The college scheme is more like a balanced ration, with so much of this and that. The necessity of attending classes in various courses at certain hours each day interferes seriously with continued attention to one thing. Yet Ido not see that the college boy of his own volition jumps from one thing to another. Given the opportunity he will spend hours on any one pursuit in which he is interested. To-day he is climbing Mount Washington, on the next stormy Sunday he may devote several hours to tinkering on a radio outfit or reading "The Plastic Age".

So that if it be the fact as I believe that college work does not contribute much in adapting men to their later lives, yet college boys themselves have created and continue to create the many kinds of active association that are a helpful and effective training for their future associations and relations to affairs.

It seems oftentimes to me as to others that the emphasis on these various extra-curriculum activities is disproportionately high but I believe the remedy is along the line of seeking for a different educational process by which the college work will make a heavier contribution to the total objective aimed at for the college graduate. If this could be found we would need have no fears as to the overbalance of college activities, especially athletics. They would then exercise their just part toward the total objective without artificial restriction or encouragement.

It is not an understanding or approval of the college curriculum or method of teaching or quality of the teachers that is causing many more boys and girls to seek admittance to our colleges now than ever before. It is chiefly the growing number of American families in comfortable circumstances. It is recognized as to boys at least that it is already a disadvantage and likely in the future to be more of one not to have the college experience. At the same time the direct object of the college work, even when understood, and it is but vaguely understood by most parents, is not generally accepted as of so much importance as the college life, the contact of young minds with each other under peculiar and favorable circumstances. I believe there is an increasing undercurrent of discontent and dissatisfaction with the scheme of the college work.

Even a critic need not agree with those extremists who consider our higher educational method as hardly more than a relic of medievalism, nor with another sort who think the college no more than a glorified country club.

Whatever the form of criticism, does it not come to this—that we do not find the formal work of the college carrying its part in the development of a man during four important, perhaps the most important, years of his life—and is not the underlying cause of this that the formal educational process is lagging behind the trend of society and civilization ?

Under static conditions of civilization the educational process may catch up with the life of the times, but in rapidly changing times it is left far behind.

If you go into the class-rooms at Dartmouth, or an}' other college so far as I know, you will find more subjects taught and with an insistence on far higher qualifying standards than thirty-five years ago, but the process you will find about the same—lectures, quizzes, recitations, sharp questions and uncertain answers; finally reviews and examinations. In most courses you will find a general attitude of getting by rather than an impelling interest in the subject.

It may be argued that all this routine work is mental discipline, and that such is the purpose of the teaching. I submit, however, that there is more downright mental discipline in even so trivial an affair as seeking for hours the reason why a Ford car will not go when it apparently should.

The trained mind comes through the mastery of successive problems, whatever time each one takes, not by the skimming over of a thousand items with so much time for each.

Of course a great teacher has an inspirational force from which youngminds catch a divine fire and are stimulated to a high mental activity which has its fruits throughout life. But these are exceptional cases and we cannot expect that all teachers will be extraordinarily gifted. Any method will fail that depends on geniuses. Our method should be such that trained, competent teachers devoted to their work can produce the results aimed at.

I am convinced that the criticism cannot be fairly laid at the door of the teachers. However free they may be to teach the truth as they see it, they are nevertheless in the machinery of an organized process of teaching in which they have been trained and which has the sanctions of age and tradition. The most casual observation shows a commendable effort and devotion on what must be quite largely a daily drudgery of hammering text-book facts and reasoning into inert because uninterested minds.

Turning now to the conditions of American life for which we are trying to adapt these chosen young men. Can anyone suppose that the college course which was suitable perhaps for the men of the seventies and eighties and nineties, the later Victorian period, is suitable to-day? Did it even fit those men for their subsequent periods? Speaking for the nineties I don't see that it did.

By the beginning of this century Victorian complacency had been challenged; a decade later it had practically disappeared as an active influence. The common man had made himself not only heard but felt. Social unrest prevailed. The country was becoming industrialized. All organizations were rapidly getting bigger and more complicated. Efficiency was the new watchword in industry. Educated men were in demand for industry and the successful ones were amply rewarded. A high degree of scientific technique had developed. And among these educated men with but few exceptions the ignorance of man's relation to his fellow man under these, or under any, changing conditions was abysmal. The average man who had graduated in the nineties knew precious little about the social and economic conditions of America and nothing at all about the rest of the modern world.

Leadership in industry and in science was at a peak of quality never before even approximated, but leadership in forward thinking, in state craft, in religion even was certainly no better (I think it was poorer) than for generations.

Then came the crash and of the sorry fragments that remained in 1918 when the bloody turmoil was over, America was easily the strongest. Not by any moral superiority, not by any sustained mental qualifications but by sheer force of numbers, natural resources, gold and industrial efficiency America was at the top. Ignorant of the rest of the world, ignorant even of itself, idealistic but not international-minded, America hesitated and despite the assurance of its public men—who were equally assured whichever side they took—the final consciousness of the people was that America did not know enough to lead the world and so should not try. It was pitiable but there it was. We salved our consciences with an outpouring of wealth to aid the immediately distressed in Europe and tried to make charity and sympathy take the place of responsibility and duty.

It would be absurd of course to charge the colleges with responsibility for this and yet I think it fair to assert that the graduates of colleges who were coming into maturity and authority in the first twenty years of this century, that is the graduates of the eighties and nineties, had not taken with them from college any practical social consciousness for the times into which they were immediately entering or any attitude of mind that could help them in the relations of nations which in their full maturity were to become so all-important.

They had been educated for a period that was already passing and their education was not especially adapted to that. Its one great merit however was that it did not try to teach them so much that they couldn't really learn anything at all. They did mostly have some capacity for sustained mental application.

It has been remarked that the modern graduate has a higher degree of versatility and a less disciplined mind than his predecessors. Naturally. That is only a reflection of the prevailing mental condition of the country. The variety of college activities and the long list of college courses, which reads so attractively in a catalogue, all add to the pressure for versatility and weaken the capacity for mental concentration and mastery of the given problem.

Granting that the temper of the war years and since is versatility rather than intellectual power is that the probable or desirable attitude of mind with which men now in college should enter active life? Is that what will count for the coming era? Can we get some glimpse of what that era will be, not of course in the sense of prophecy as to particular events, but rather in the underlying trend of the times. Some forward-thinkers have been studying this.

In The Mind in the Making, Prof. Robinson calls attention to what he describes as "the shocking derangement of human affairs which now prevails in most civilized countries including our own" and later on he says "we have first to create an unprecedented attitude of mind to cope with unprecedented conditions and to utilize unprecedented knowledge".

This unprecedented knowledge lies at our hand not only in the astonishing achievements of scientists and their practical applications, but in the remarkable and already fruitful attempts to explore by scientific methods the social, political and economic relations of men to each other.

The practical relations between men, and to a considerable degree between nations, have been revolutionized during the past half-century by science as applied to communication, transportation and power. This process is still going on with its obvious applications of machinery to the daily life of everybody. Some look with fear on this situation as meaning the domination of man by the machines of his own devising and there is some force in this reasoning. But I feel strongly that this is neither necessary nor probable, that on the contrary man has now and henceforth always at his hand new tools which merely extend his powers in strength, speed and space. Each of these extraordinary tools after man's first absorption in it, like a boy with a new toy, will find its place in the toolchest whence it will be taken out for use only as his real needs and interests require it.

We have not yet properly related all this application of new knowledge to living. We are still playing with our new tools. We are barely beginning to apprehend what they mean as related to the moral and intellectual life of society. We are not putting hard serious practical thought into the future of society.

H. G. Wells expresses the thought (I do not quote him exactly) that when the intellectual history of this time comes to be written nothing will stand out more strikingly than the gulf between its superb and fruitful scientific investigations and the general thought of other educated men.

This seems to me sadly true and because our general thinking is vague, sloppy and swayed by prejudices and partisanship of many kinds we are the prey of propaganda.

It is said we have no time for really thinking in this whirling civilization. Not many years ago men worked from ten to fourteen hours a day for their daily bread. Now in eight hours or less, thanks to the practical applications of science, they earn much more than bread. Only defective mental concentration and lack of will power stand in the way of more time than ever before for acquiring information and forming judgments outside the realms of one's work.

Moreover, in every hour of time much more can be accomplished in the machinery of mere living, the chores of life. Swift transportation, quick communication all make for that. But thinking is no easier than ever. It alone has no short cuts.

We who are the other educated men meant in Mr. Wells' comparison with the scientists may admit with shame the justice of his indictment as to our generation. We have seen a world plunged into misery by our ignorance, our inattention to the problem of a social and international order adjusted to the modern conditions of applied science and we have in effect admitted our inability to cooperate or lead others to co-operate in such practical policies as might offer some hope of future social safety.

The trend is clearly toward further invention of scientific contrivances and their wider distribution into common use by all people. The trend is toward greater populations more closely packed together and toward the increasing difficulty of raising enough food for them shown already in the disappearance during our own times of America's unutilized "free" farming land. The trend is toward even more complicated social problems while many of the old ones still press for solution. The trend is toward more international relationships whether welcome or shunned, whether friendly or hostile. Now with these scientific, economic, social and political trends coming on apace what spiritual reactions there may be I do not venture to suggest.

In this field as in the others there will be leaders and the quality of their leadership, now assuming extraordinary importance will depend more on the American colleges of to-day than on any other factor.

The English socialist, Bertrand Russell, certainly no friend or admirer of our country, says in his latest book ''The future of mankind depends upon the action of America during the next halfcentury."

What a responsibility lies before the coming men of education and quality and what a glorious opportunity! Unprecedented knowledge is here, many unprecedented conditions are already here and still more are clearly coming. How then about the unprecedented attitude of mind to use the knowledge and meet the conditions ?

That attitude of mind should be first, of all a search for the truth, a testing of it by experiment, a critical study of its experimental results and finally after check and recheck, a readiness to make it a part of one's life and thinking. That of course is the scientific method and to it we can trust any proposal of social, economic or political change.

In the willingness to look forward but to insist on the scientific method of test of new ideas lies the opportunity of the colleges to-day. And they will not meet it by any scholastic system, however hallowed by time, that fails to enlist the whole-hearted interest of students in the college work as something related to the kind of world in which they are going to live.

Not many students will be interested in deciphering the inscriptions on the gravestones of man's history, but they need and I think want a simple outline of his evolution through the ages for in it they may see the possibilities of his future. They need, and I think want, some knowledge of the processes of man's mind and thinking, for most of them expect to think even if they have not already begun to. They need, many of them crave, some knowledge of the beautiful, in art, in music, in literature and in life. They need and, whether they go to college or not, will get some acquaintance with the practical fruits of man's scientific achievements and of the principles on which scientific research is based. Much more they need and much of it they want, but they, like their elders, want it in some perspective rather than as unrelated facts. And I believe that want is based on the sound instinct of utility, not a narrow utility for their own schemes of earning a living but the broader sense of what will go into a useful life of individual, group or nation.

Nor shall we really get anywhere by trying to impose on them those things we think to be eternal verities. Each generation must be free to examine the validity of every premise, every argument, every conclusion of its predecessors, for only so will the truth appear, and only so will the truth be a vivid and vital influence in men's lives.

In the past few years Dartmouth College has gained some reputation for intellectual fearlessness. The college policy has been to bring before the student speakers, even of extreme views, who represent different standpoints on questions of great public interest. Capitalism, socialism, fundamentalism, modernism and other acute controversies have had their innings. Many things have been said by these speakers with which I like many others thoroughly disagree. But I am convinced that this is one of the wisest policies ever adopted by the College. It makes for an intellectual freedom that would have been inconceivable thirty-five years ago. Besides that it is the only honest kind of education and I believe the only safe kind. It is one way of seeking the truth. I exclude it entirely from my criticisms of the educational process. And in these criticisms of our college system I do not refer to Dartmouth more than to all the other colleges of the liberal arts. We are concerned with them all for they are of vital significance in our common American life. But we are responsible for Dartmouth. It is a joint responsibility in which every one of us shares. And that means more than the waving banners and rousing cheers at our football games. It means seeking the truth about our educational system and it means saying what we really believe about it. He is a weak friend of the college who merely approves it without thinking about it, forming opinions and expressing them.

Every step forward Dartmouth makes I like to think of only as a bit of progress, not at all as reaching a goal. And I think our next important efforts should be on the educational process not only that it may be done better, but that it may be more closely related to the coming life of America.

My viewpoint may not find acceptance. Certainly I should wish it to be criticized from other viewpoints. And in any case it is an attitude of mind for which I argue rather than .a specific program.

There are signs that we are on the verge of a great awakening of intellectual activity and that its form will not be like anything of the scholastic past. It will I hope lose nothing of vital good that the past has for us, but it will be predicated on the changed and still changing conditions of the world. In this awakening Dartmouth has already a significant part so far as the American colleges are concerned. It has even an opportunity for leadership unprecedented in its history. And that opportunity comes to us because in every respect but one we are ready for it and equal to it. We have a rare unanimity among alumni, trustees, faculty and undergraduates of faith in our leadership and we have already an unusual spirit of intellectual interest among undergraduates.

The only handicap we see toward grasping this unprecedented opportunity is financial. We are keeping within our means only by economy of managementwhich is wholesome—but our ability to do bigger and better things in the direction of which J have spoken depends on the response of the alumni. Not alone because we are grateful for what Dartmouth has given us, not alone because we are responsible for her future do I urge a generous support of the Alumni Fund, though these would be reasons enough. Rather it is an opportunity to take a direct part in no less a causeand I measure my words, gentlementhan saving the quality of our civilization by more intelligent education which alone is the hope of the modern world.

Trustee of the College

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE POW WOW

April 1924 By E. Russell Palmer '10 -

Article

ArticleThe Chicago Pow Wow which

April 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

April 1924 By H. Clifford Bean -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

April 1924

Article

-

Article

ArticlePresident Hopkins Speaks on Educational Unity

May 1933 -

Article

ArticleClass Funds Near Million Mark

October 1952 -

Article

ArticleWinter Schedules

DECEMBER 1972 -

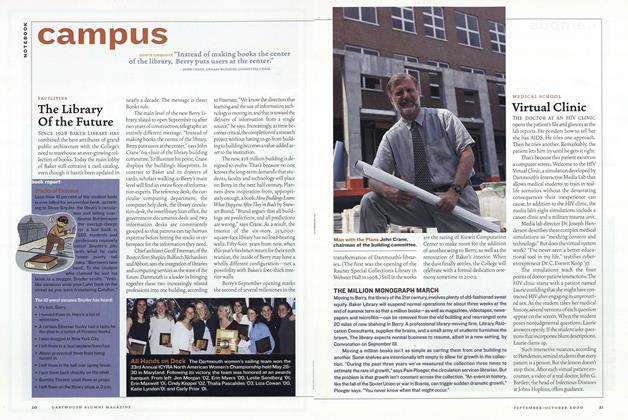

Article

ArticleThe Library Of the Future THE MILLION MONOGRAPH MARCH

Sept/Oct 2000 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards

Nov/Dec 2008 -

Article

ArticleRoom to Grow

July/August 2011