no difference in the avenues of approach thereto, it seems entirely wise and right to end the meaningless distinction between the degrees of Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science as conferred at Dartmouth, and to confer hereafter only the A.B. degree—as was decided late in the spring by . the authorities at Hanover. The B.S. degree was in fact mainly a relic of the days when.there really was a pronounced difference between the training which a student in the Chandler school courses received and that which was given to a student in the academic courses. It had softened to a minor difference between those who had studied Latin and those who had not, without really implying any special attention to sciences worthy to constitute one a degreed Bachelor thereof. As it stands now, the man who pursues his four years' course at Dartmouth hereafter will receive at the end a parchment certifying him to be a Bachelor of Arts.

The intricacies of the curriculum leading to this degree we hardly feel qualified to discuss. The tradition, of course, has long been that the A.B. degree should connote at least a bowing acquaintance with Latin, though the world long ago gave up the idea that it should also imply a similar acquaintance with Greek. Possibly the making of A.B.'s who have ignored the classics altogether will strike some as a final surrender of the last remaining bulwark of true culture. It may be pointed out, however, that comparatively few will reach the coveted estate of bachelorhood without ever having studied any Latin at all; and it is likely to be further asserted by some that those who have studied Latin will, in most cases, be nearly as unacquainted with it by Senior spring as are those who never had any.

If we understand the curriculum as outlined in various bulletins, it is possible for a candidate for the A.B. to avoid the Latin classics entirely, by making his choice at the outset of his course among the various groups required; but, for a guess, the instances of this will tend to be fewer rather than more numerous as time goes on, because of the very obvious fact that without any Latin at all one is seriously handicapped in one's use of other tongues—by no means excluding English. It is time it were more generally recognized that while Latin is a "dead" language, it is at least the ancestor of a multitude now living and as such is worthy of the living's respect. Linguistic genealogy deserves to be made more of by our present age.

It is possible also that calling a graduate an A.8., rather than a 8.5., will not make him an A.B. in spirit and in truth; but that is a matter which rests with the arbitrament of time and of custom in the cultural world. For the moment the MAGAZINE inclines to regard the decision recorded by the Dartmouth administration as practical and wise, at least in view of the facts as they now obtain. But it would admittedly please us even better if the requirements which go to make an A.B. could be somewhat more rigidly standardized than at present they seem to be.

The other interesting feature of the changes decreed as a result of the researches by Professor L. B. Richardson and the deliberations of the faculty committee in charge of the matter, relates to the greater freedom of the "honor group" of students during their last two years in college. This is an experiment which assumes a sincere purpose on the part of the exceptional few to make the best of their opportunities without the constant oversight and driving of professors. Such as qualify for this distinction will have their own salvation, academically speaking, largely in their own hands; so that while they are required to follow certain major lines they may do it in their own way and in their own time, instead of being held to a hampering routine. Special attention of an individual sort will be given to such, as desired; but a freedom vastly exceeding that of the ordinary run of students will be open to those who seem capable of using it without abusing it.

This expedient, we believe, is not entirely new in colleges. If memory serves, one or two have already made trial of it with satisfactory results. It goes without saying that the selection of men to enjoy this privilege needs to be made with appropriate care, and even with such care there will necessarily be occasional instances of mistake. Not every extragood student will be found proof against temptation to postpone his serious work until too late to enable his meeting the requirements For a guess, however, the cases of that kind will be few; and in the majority of instances the work done ought to be considerably better than the same men would be enabled to accomplish if held to the old-time routine of classes, in which, as in fleets at sea, the velocity of the mass is regulated by the slowest units. It is a device to enable those capable of showing speed to make full use of their powers unimpeded by handicaps.

In any case the alumni of Dartmouth will, as always, be found in cordial sympathy with the endeavors of those in di rect control of the college policy to improve the work done by the successive classes and to commend the output to the world into which it goes to live and work. The alumni's disposition is always to recognize the greater fitness of experts to judge of such matters, as against the snapshot judgment of men devoid of practical acquaintance with college problems, or with educational tendencies, such as most alumni not themselves employed in teaching unquestionably are. The president, trustees and faculty are deservedly trusted by all of us to do the best things as they see them; and their judgment, so often approved in past years, may be assumed to continue to be most excellent.

The College has closed another year. It faces a future succession of years with every hope and every confidence. In the unfolding of those years it proposes to make use of what seem more promising means to carry its educational benefits to new and greater heights. In that, as a matter of course, the College may count upon the unswerving loyalty of its sons to give every assistance in their power.

The attention of thoughtful educators may well be concentrated on a phase of our democratic development which has its disquieting features and which has begun to be rather widely commented upon. It is an underlying theory that the better educated the people of a country become, the better their government is bound to be. It is pointed out, however, that while public education in the United States is today more widely diffused than ever, and while more people regardless of class and condition are sending their sons and daughters to college than ever before, there is no corresponding improvement in the government of either the country, the states, or the cities and towns. On the contrary the average commentator appears to believe that democratic government in the United States is worsening.

It is hardly to be denied that there are plausible grounds for that belief—certainly with respect to the government of cities, where democracy has always scored its least conspicuous triumphs, and to a great degree also with respect to the various commonwealths that go to make up the Union. There is a general accord in the proposition that since the United States senators became subjects of direct popular election the result has been a deteriorated quality in the upper house. One may sum it up by saying that no one seriously claims our politics to be growing better pari passu with the spread of education, but that on the contrary a well formed conviction exists in many quarters that the tasks of government seem to be less and less well performed, year by year.

If this be true, and it is not the present purpose seriously to question it, something may be wrong with education. In view of the wide diffusion of learning through compulsory schooling, it is fair to assume that the general average of American intelligence is being steadily raised. In view of the prodigiously increased demand for college training and the huge armies of young men and women now annually enrolled in our higher educational institutions, it should be clear that an even greater advance in the average intelligence must be made. If this does not produce the expected and indeed the logical effect in American politics, how comes it to be so? In fine, why is it that education shows its effects clearly in general industry—which it obviously does—without manifesting any similar effect in the matter of the country's po litical standards?

It can hardly be claimed that the country is not receiving education. If ever the people of any country were well schooled, the present Americans are so. Lord Bryce, than whom there was no more sympathetic and no more accurate observer of the American commonwealth, long ago pointed to the great underlying theories of all democracy when he said that the sustaining doctrines were two: 1, that the gift of the suffrage creates the will to use it; and 2, that the gift of knowledge confers the capacity to use the suffrage aright. "From this," he says, "it is commonly assumed to follow that the more educated a democracy is, the better will its government be." But is it working out so? Apparently not. Perhaps the defect is that while the gift of knowledge "creates the capacity" to use suffrage aright, people are not making full use of that capacity. In other words, they could but they don't. It has lately been revealed that even in our national elections nearly half the entitled voters usually omit to exercise their right to vote—a record in which our democracy shows to little advantage when contrasted with Australia or New Zealand. Wherefore the question is raised whether or not education is sufficiently concerned to inculcate the wise use of wisdom. It is quite evidently and very eagerly used by millions to improve their individual condition, but it has thus far no corresponding effect on the improvement of the collective condition of states.

For a helpful discussion of this general topic as it bears on the higher education of the day, the reader is referred to an article by President Angell of Yale in the April issue of the Yale Review. The danger is that our education, other wise so productive of good, falls lamentably short of promoting public spirit and the desire to serve the commonwealth in the same measure that one is inspired to serve one's personal advantage. Dr. Angell hints that part of the failure may be chargeable to the family and the church; but it is entirely probable also that our educational system must bear its appropriate share of the blame, and to that end one suggests the prayerful thought of the wise men who direct our American colleges.

William Allen White, the sage of Emporia, Kan., lately delivered a commencement address before a graduating class of one in a western high school, which has received a considerable amount of attention. The kernel of the Kansas editor's speech lay in a little dictum relating to the desirability of having the country get better acquainted with itself, the earlier the better. Mr. White mentioned as an ideal course of conduct that "western boys should go East to college, and eastern boys, West."

Comment on this suggestion, which is really a development of the Cecil Rhodes theory, has been varied. Taken too literally it is open to criticism. One is moved to inquire whether the same reasoning would not apply as between North and South—imposing a rather embarrassing quadruple choice on one born and reared in this geographical centre of the country; or whether Mr. White is quite fair to the aspiring state of California, where is located a prodigious university which not only offers education but actually gives it free. California, however, may be depended upon always xto take care of herself, whether the question of the moment be climate, citrus fruits, or general culture.

Mr. White, however, has made his point and the point is, within proper limits, a good one. It is fair to remark that the experiments made thus far in the Rhodes scholarship at Oxford indicate a partial success, only, in producing a greater sympathy on international lines. The mingling of students in formative years from various quarters has not invariably prompted cordial fellowship. Nevertheless it is clear that it ought to, and in the majority of instances it probably does.

Looking at it from the other end and emphasizing a phase of the question which Mr. White seems not to have stressed, it may be added that the suggested exchange between sections ought to be a very excellent thing for the colleges themselves, as well as for the individual students. Something very like this idea has been embodied in the selective process of admissions to Dartmouth, with its stress on the desirability of distributing the student body over as many states as possible. If published figures are correct, the undergraduate college of Harvard University has at present, for example, only two students from Kansas and only 10 from Missouri —whereas Dartmouth, with a much smaller undergraduate body but selected with geographical distribution in view, has 16 from Missouri and eight from Kansas. This feature of our selective system has been subjected to criticism—• perhaps more criticism than has been poured out on any other one feature of it; but one gathers from the address of Editor White that at least no objection would be raised by him. The Dartmouth theory is that a college made up of rep- resentatives drawn from all over the great territorial expanse which we call the United States is bound to be a better college than one which is too largely provincial in proportion to its total undergraduate membership.

On this point there has arisen some difference of opinion, some educators holding that the important thing is to take the very best specimens scholastically, even if they all come from a single section. That is certainly not the theory at Hanover. Dartmouth believes thoroughly in considering several other elements in addition to mere scholarship as expressed in marks, feeling that a boy in college profits more in the long run from association with other boys from all sections of the country—even if their marks in academic courses be not quite so high—than he would by association solely with extra-scholarly New Englanders. That is to say, his intellectual and other capacities will probably be the better enlarged and improved in the former case, especially as Dartmouth is by no means inclined to admit an ignoramus merely because he comes from some unrepresented section.

William Allen White is noted for emphasizing truths by expressing them in a striking, if often exaggerated, form. In this case it seems to the MAGAZINE that he has touched on a very vital matter and has caused it to be discussed in a way which should be productive of genuine good. That it lies in a direction already pioneered by our own College does not diminish, of course, the favor which one feels toward the general notion at Dartmouth.

Flaming youth, in its fashionable passion for what it usually calls "challenging" the theories and practices of its elders, has lately at Hanover called in question various college traditions,—some of them not very old to be sure, but still dignified by the name. Reactions to the process will vary with the individual, of course, but one feels a certain sympathy with the demand that traditions shall be, as the Daily Dartmouth puts it, "evaluated," to the end that such as have no worth may be cast aside, while such as appeal to the undergraduate intelligence are perpetuated in honor.

One hesitates nevertheless before the knowledge that not every traditional practice is susceptible to accurate mathematical or rational evaluation. It is sometimes worth one's while to retain a custom that has little of logic about it and comparatively little, or possibly no, power to perform a very tangible service. The world is full of such things, hallowed by long custom and possibly useful once, but kept up mainly because they always have been. In the colleges especially there are bound to be certain avenues for the escape, more or less harmlessly, of youthful spirits in the form of established inter-class contests; and it is chiefly with respect to these that the conflict has arisen, often as it seems to the MAGAZINE with very good reason behind the propensity to rebel. It may not be amiss to assess the merits of such things in hope to discover whether they do good enough to warrant the bother they entail. Our one serious objection would be to "challenging" traditions merely because they are traditions, as if there were necessarily a virtue in questioning things on the score of age or custom alone.

We are adjured by the minstrel to set a watch lest the old traditions fail; and by this it is fair to assume are meant those traditions of w.hich one has no occasion to be ashamed, or which go to make up that famous collective intangibility known as the Dartmouth spirit. The fact that.a custom is of traditional quality does not of necessity discredit it; and while it may not prove the custom to be a worthy one, at least the fact that it is traditional seems to us to warrant a presumption in its favor at the outset, to be rebutted if at all by evidence of respectable weight. In other words, when we are evaluating, let us really evaluate and not merely revolt against something because it is old and because we are young.

It is further to be remembered that all wisdom is not vouchsafed even to the younger generation at a given moment,, so that to make it a court of last resort for the final evaluation of things collegiate may be injudicious. One suspects that there are numerous college customs in every institution like our own as to which alumni opinion, after a lapse of years, will coincide almost exactly with an unfavorable undergraduate opinion and thus condemn such traditions without dissent as undesirable to continue. The process of assessment should not be a hasty one. This year's class may concur with last year's in voting to be ridiculous a custom which has obtained for a score of previous years; but it may still be matter for doubt that the doing away thereof is destined to be the unmixed benefit which opinion for the moment assumes. One inclines to regard the inertia of an established tradition as at least some evidence, of worth, and would prefer to apply the doctrine that at least it is innocent until proven guilty. There have been times when it looked as if the undergraduate proposed to hold it guilty unless it could be proven innocent- largely because impetuous modern youth is inclined to regard with suspicion pretty nearly everything its predecessors have held in reverence. The sinning isn't all on one side.

Two or three topics arising out of the Commencement season ought not to pass entirely unnoticd in this issue of the MAGAZINE, althougJi considerations of space forbid extended comment at this time. Particularly is this true of the important decision of the Trustees to advance the tuition charge, beginning one year from this fall, from its present figure of $3OO to $4OO a year. Whether or not there is at present a higher tuition fee in any college of Dartmouth's class we do not know—and it is not especially important. It is inevitable that many other colleges will eventually equal this figure and that some will possibly surpass it, because it is increasingly imperative to make what the student pays bear a more equitable relation to the cost of his instruction. Even at $4OO it is clear that there must still be a very noticeable deficit, which must be made up as usual out of other funds and principally by contributions of the alumni. The factor which holds down the tuition fee is, of course, the important consideration which would preclude making ours a "rich man's college," Open only to those who could afford a much higher payment. No one, surely, wants to see that happen. The great question is whether, at $4OO, this charge has been pushed to the utmost limit consistent with the proper democracy of such a college as our own. Much depends on the ability to make scholarship funds adequate to the needs of desirable students who would find $4OO a year too much for them to pay, but whom we .most certainly wish to retain and who themselves make up the backbone of the Dartmouth fellowship.

Closely allied with this is the momentous decision of the class of 1925, responsive to a talk by Mr. Henry H. Hilton '9O, in which that class undertakes during the next 25 or 30 years to reimburse the college for the difference between its actual payments in tuition fees and the actual costs of its education —estimated at about $lOOO per student for convenience. This is tantamount to pledging between $330,000 and $350,000 to the College—the repayments being distributed over a great many years, but constituting in the aggregate a sum exceeding that which any other class has ever promised or paid as a class. The idea is entirely logical. Young men unable to bear the full cost of their education at the time agree to make up the deficit later, when they may do so without undue hardship. It goes without saying that if this plan is generally adopted, following the 1925 decision as a precedent, the labors of future Alumni Fund committees will be greatly lightened.

As it stands now, however, this project is only on its threshold and will be some years in making itself felt to the degree which will affect importantly the contributions which alumni must make if the College is to close every fiscal year "square with the board." In, consequence it is to be expected that this past season's quota ($90,000) will be materially increased for the year about to open. By what amount remains to be established—but it will be well to heed the candid statements made at various alumni gatherings during Commencement week that one must be prepared to see the total of next year's fund appreciably augmented, to the end that the College may deal justly both with its faculty and its students. The commanding successes of the Fund campaigns this year and last suffice to warrant a belief in the ability of the alumni body to shoulder an added burden, so long as it is kept within reasonable bounds. Ten years ago, no one would have dared predict that in 1925 the graduates of the College would raise $90,000 —but that has actually happened. What every one hopes is that in the decade that lies before us our endowment and the ordinary income will be so stabilized that the Alumni Fund may safely be diminished. For the moment we are at the cross-roads and the only decision that any one will countenance is that we go forward.

Other interesting topics, such as the decision to revive chapel services on a voluntary basis and the declination of the Phi Beta Kappa society to lower its standard in' response to the demand of some undergraduates, so as to admit of certain elections where rank is insufficient by itself, must await a later season for consideration in detail. At the moment the editors of the MAGAZINE will content themselves with saying that they believe both decisions to have been wise, although cognizant of numerous arguments for a contrary determination in both cases, which are certainly not devoid of cogency.

The closing report on the Alumni Fund reveals the fact that in the fiscal year closing with June 30 the graduates of the college responded even more nobly than usual to the call of the managers of the Fund and exceeded the established quota by several thousand dollars. Setting a mark of $90,000, Mr. Priddy's committee announce a total of rising $98,000. It is in itself a sufficient comment on the great effectiveness of the work done by Mr. Priddy in his first year as chairman and chief engineer of this campaign and by Mr. Booth, executive secretary of the Fund Committee. There have been notable achievements in this line before but this one stands as a record until it is bet tered. Congratulations may well be general—not only to the men who gave so abundantly and so successfully of their time and energy to this task as managers of the campaign, but also to the whole body of alumni whose cordial generosity made this record possible.

The death of Dr. John M. Gile which occurred as this issue of the MAGAZINE was going to press removes one of the leaders in the present-day life of Dartmouth College. The welfare and progress of the College was close to his heart. No one has worked harder or more successfully to advance the interests of the community. For a term of nearly thirty years he gave himself to the Medical School at the same time using his unusual ability as a surgeon throughout the state while he worked unceasingly as a trustee and member of the staff of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital.

The same devotion was given to the position of trustee of the College, which Dr. Gile had filled since 1912, and the records of that body will reveal the scope of his work. His influence was felt in the councils of the state government and in its war-time organizations. He gave unstintingly of his time and strength and few are called to fill so large a place in such varying fields of activity. The College, the community and the State are the poorer for his going but the record of accomplishment remains.

The Faculty line

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

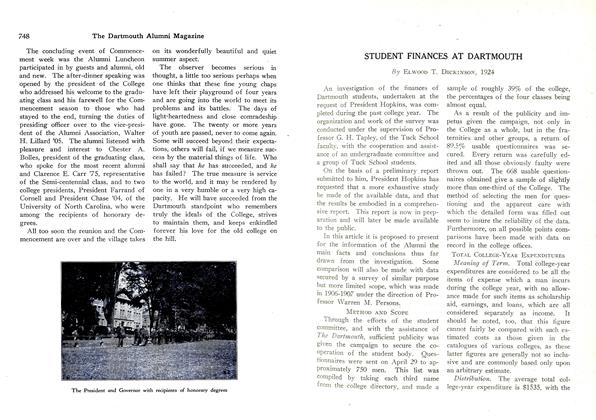

ArticleSTUDENT FINANCES AT DARTMOUTH

August 1925 By Elwood T. Dickinson, 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

August 1925 By Perley E. Whelden -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1925

August 1925 By Natt W. Emerson '00 -

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1912

August 1925 By Alvaro M. Garcia -

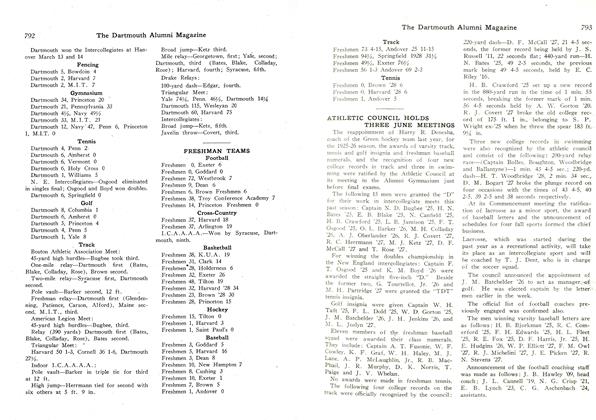

Sports

SportsATHLETIC COUNCIL HOLDS THREE JUNE MEETINGS

August 1925