A very practical part of the reconstruction work following the war in other countries is the sending to this country of promising students who are expected to later return and lead in the rebuilding of their shattered native lands. Serge Jurenev, now in the Amos Tuck School, is one of these men. He receives some aid from the Russian Student, Inc., and the following article taken from its monthly publication is of much interest not only for the insight it gives into the work being accomplished but also for the graphic picture of conditions across the water:

"Serge Jurenev, senior at Amos Tuck-School, Dartmouth, considered one of the most brilliant students of business, is commended by Dean W. R. Gray: 'Having made what we consider a remarkably brilliant record in the face of obvious handicaps, Jurenev was naturally expected to continue his excellent work. We did not anticipate, however, that his completed record for the year would place him at the head of his class. The fact is he received A in each of the six courses of his schedule. We have other brilliant students who have made records equal to that of Jurenev, but they are few. None, however, worked under the limitation imposed by unfamiliarity with the language and the customs of American institutions. None, moreover, had to give so much time and effort to the amount of outside work which Jurenev carried as a means of financing his expenses for the year.'

"Jurenev's father, general manager of a shipbuilding yard at NiCholayev, was murdered by the Bolsheviki in 1919. Jurenev came to the United States through Constantinople and Prague with the help of the American Red Cross and the European Student Relief, and he fully justifies the confidence placed in him by the Russian Student Fund, Inc. What he thinks the Russian student can do for himself and others can best be told in his own words.

" 'The Russian Student—you will find him everywhere. After years of hardships, he has not lost his spirit. Far away from home he works with one thought—to work again in the fields and towns he had to leave. I remember well the moment when crying women and children and men with stony faces and eyes, in which one could see tragedy and despair, went up the gangplank to leave their country as refugees.

" 'At Perecop, where the Crimean peninsula joins the continent", my friend and I sat on a slowly rolling gun. His face was gray with dust; his coat torn by a piece of shell. "You know," he said, "there is some hope for us. How I hate all this. I wish I were in my room again, with my books, sitting at my desk instead of on, this machine of death. Why is it that our generation has to go through this? All this is a nightmare from which we shall awaken." We were behind a low hill, hidden from the enemy, and our observation point was in front of the top of the hill. "Battery be ready!" We started to fire. There was no infantry in front of us and we tried to stop the advancing enemy. Soon an armored car advanced from the left and moved swiftly to- wards us. Our third shot tore it to pieces. We moved back to our main forces. My friend, who was chief, ordered the machine to stop as we had lost an aiming instrument. I limped badly after my last wound and could not follow him. Presently he returned and we fixed the harness on our horses, and started off again. The horsemen let the horses run as fast as they could. A sudden jar made me turn and I saw the pale face of my friend under the heavy wheel. For a moment only we stopped! I limped towards him and picked him up. His chest was crushed, and the bullet which had caused his fall, had passed through his stomach. "Remember what I told you about a room and books. I will never see them again." "Don't be foolish," I said and tried to smile. "Please; will you give this to my mother?" He handed me the gold cross which he always wore. The next day-we car- ried his coffin on the gun to a simple grave in a nearby village. We never reached his native city, and his mother died before I could trace her from abroad. I was given his job and thought that my turn would come next. But it didn't.

" 'Almost a year passed. I was in Constantinople—that big city crowded with Russian refugees seeking work. We ceased to be soldiers. Any kind of work was acceptable to a Russian student, but it was not easy to find it in a city where there were no industries. The American Red Cross saved us from starvation. A Russian who went through seven days on a ship crowded with human bodies, with-out food for four days and one-eighth of a pound of corned beef and a slice of bread for the other three, little water, will never forget the A. R. C. Life was hard. Nobody dreamed of finishing his education. Only at night, one could hear people in ragged clothes discussing literature. A year passed and everybody was trying to get to some other country to live and work, but there was no chance. A few of the most daring tried to walk across the frontier, but returned. There was no way out of Turkey.

" A little new country which had undergone hard experience during the War and had become independent—a country with small resources and a big heart—resolved to accept a few Russian students. The students had to pay for their trip, and there was no way to raise the money. That big and powerful country which understands human sufferings—the United States—gave help and transported 300 students to Prague.

" 'There are few who' have had the chance to get to this country and study. " 'The spirit of industry still exists in the Russian student and helps him to struggle, to live to become a useful citizen of his mother country which he loves. It is the goal of his life to return and serve her. He is striving to prepare himself to be a constructive worker. Russia needs fresh forces in the process of reconstruction. At the Statue of Liberty which guards the entrance to this great country, we who are in the United States will light the Torch of International Friendships and Peace, and we will carry home the light of high principles acquired here.' "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE LIBERAL COLLEGE

February 1925 By Leon B. Richardson '00 -

Article

ArticleProbably, despite the widespread

February 1925 -

Article

ArticleSOME UNPUBLISHED LETTERS OF RUFUS CHOATE

February 1925 By H. D. Foster -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICAL FITNESS

February 1925 By Dr. William R. P. Emerson '92 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1925 -

Article

ArticleTHE THIRTY-FIFTH REUNION

February 1925

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROGRESS OF BUILDING OPERATIONS

November 1920 -

Article

ArticleLARGE DEMAND FOR OUTING CLUB HANDBOOK

March 1925 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Club Luncheons

November 1949 -

Article

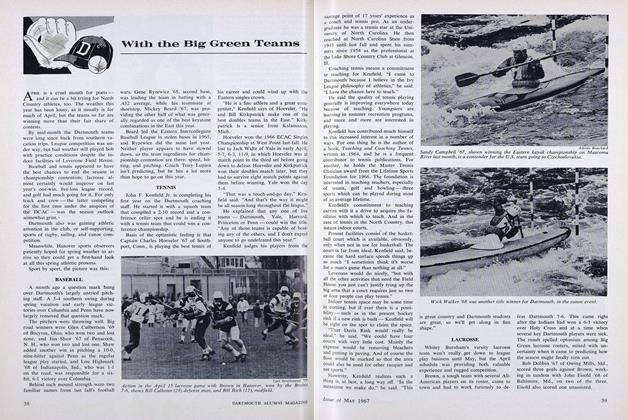

ArticleTENNIS

MAY 1967 By DAVE MARTIN '54 -

Article

ArticleAll Shook Up

MAY | JUNE By Gavin Huang ’14 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

January 1945 By H. F. W.