Adjoining the ancient meeting house, on the "one acre north of the green" granted by Eleazar Wheelock in 1777, there still stands the dignified colonial dwelling built and occupied by Sylvanus Ripley, member of Dartmouth's first graduating class.

Young Tutor Ripley, '71, was an attractive all-round personality, with something of Wheelock's power of making friends of all sorts of people. As a youthful missionary, just out of college, he persuaded the Canadian Indians to let him take back to Dartmouth "ten little Indian boys," despite the objections of the priests. He was so effective a speaker that Governor John Wentworth persistently but vainly sought him for King's Chapel, Boston. College trustee at twenty-six; at thirty, pastor of "The Church of Christ at Dartmouth College", adjoining his home; three years later, Phillips Professor of Divinity; chaplain in the Revolutionary army; active in all sorts of academic, religious, civil, and military affairs,—he was successful in inspiring in others the loyalty and courage he himself possessed. When only thirtyseven he met his tragic death, going forth from this house during the snowstorm of 1787, in loyal pastoral care for the whole community. Sixty years later an old man writing down memories of his own Hanover boyhood bore this hitherto unpublished testimony to the lovability of Ripley.

"He knew all the children of the village (and precious is his memory to one still left) and they all knew and loved him and were as sensible of their loss as the older population."

To this house, the young trustee-professor-pastor had brought his wife, Abigail Wheelock, daughter of the founder. Their four children, following the precedent of their parents, established the tradition faithfully observed for a century and a half by no fewer than thirtysix of this house of Dartmouth. The men took bachelors' degrees from Dartmouth; the women took the bachelors. The oldest son, John Phillips Ripley, (Dartmouth 1791) in 1795 went to Poland and joined her army fighting for liberty against the Russians. He became an officer, was captured and imprisoned for eighteen months by the Russians, but luckily succeeded in concealing and destroying papers which would have caused instant death if discovered. His younger brother, Major General Eleazer Wheelock Ripley (Dartmouth, 1800) received from Congress a gold medal for conspicuous gallantry in the war of 1812.

Elizabeth Ripley, oldest daughter of the house, married Senator Judah Dana of Maine (Dartmouth, 1795). She must have been a remarkable woman, if we accept the enthusiastic description and Shakespearian quotation of a schoolmaster of twenty, to whom she and her husband were good neighbors and friends in Fryeburg, one Daniel Webster, college mate of Elizabeth's brother at the time of her wedding in Hanover.

In 1797 Freshman Daniel Webster spent his first night in college in this house. First-hand evidence of this is given by a fellow student, Roswell Shurtleff '99, then entering as a Junior.

"I put up with others at what is now called the Olcott House, which was then a tavern. We were conducted to a chamber where we might brush our clothes and make ready for examination. A young man, a stranger to us all, was soon ushered into the room. Similarity of object rendered the ordinary forms of introduction needless. We learned that his name was Webster, also where he studied, and how much Latin and Greek he had had, which I think was just to the limit prescribed by law at that period." "Mr. Webster, while in college, was remarkable for his steady habits, his intense application to study, and his punctual attendance upon the prescribed exercises." "He emphatically minded his own business."

This was the public statement of the scholarly Professor Shurtleff, as chairman of a meeting in Hanover, October 25, 1852, commemorating Webster's death, reported in the Boston Journal ofCommerce, November 5, and quoted in Professor Lord's History of DartmouthCollege (p. 304). There is an independent account in the Boston Evening Traveler, October 27. Charles Caverno '54, present at that meeting, also records (in his Reminiscences of Choate's Eulogy) Shurtleff's words about Webster's minding his own business. Professor Shurtleff is a good witness, a man of vigorous intellect who as a fellow student and tutor knew Webster well, and his public testimony, confirmed by his statements to his daughter, Mrs. Susan Brown (printed by Professor Charles F. Richardson in his Webster Centennial address) gives ample and reliable evidence that Webster and Shurtleff "put up" at the Ripley-Olcott-Leeds house, their first night at Dartmouth.

Shurtleff is a memorable figure because of his connection with the famous Dartmouth College Case. As Phillips Professor of Divinity, and pastor of the "College Church," he stood up manfully for academic and religious freedom against the autocratic attempts of the second President, John Wheelock. His refusal to be manipulated by the President in either church or college was the immediate occasion for a conflict which passed beyond church and college into state politics and resulted in the attempt of John Wheelock and his political supporters to annul the college charter. The suit in behalf of the College in this famous case, precipitated by Shurtleff's manly independence and won by his old college friend and pupil Daniel Webster, was brought by Mills Olcott, treasurer of the College, whose home was the quondam tavern where Shurtleff and Webster had spent their first night in college. Squire Olcott had bought the house in 1801 from Richard Lang, keeper of the Cobb's store of that time, and money lender, among others, to both Dan and Zeke ' Webster during their college course. In 1817-1818, Treasurer Olcott, in the house built by a graduate of Dartmouth's first class, on land granted by the founder Eleazar Wheelock, records the sums contributed by Richard Lang, Daniel, and Ezekiel Webster, to help the College when its charter and life were threatened. The white house on its "one acre north of the green" is the one college building on the campus still remaining as a visible reminder of "Dartmouth founded by Eleazar Wheelock, refounded by Daniel Webster." The "loyal sons of Dartmouth" connected with this house helped to win for the College intellectual liberty and union. A generation later, Webster, on the same fundamental principle of loyalty to obligation, risked his reputation in his 7th of March speech to save political liberty and union for the nation.

From 1801 until after 1845, the house was the home of at least three generations of Olcotts. Peter Olcott, trustee of Dartmouth for twenty years, former Judge of the Supreme Court of Vermont, came across the river to die at his son's house. For more than a generation it remained the dignified Olcott mansion, home of that son, Mills Olcott, Esquire (Dartmouth 1790), for twenty-nine years college treasurer or trustee, one of the most prominent men of the region, deservedly honored for his business initiative and sagacity, beloved for his humor, poise, and the generous hospitality of an old fashioned gentleman. President Monroe's call at Squire Olcott's house in 1817 was a matter of course; for more than half a century it was the port of call for distinguished visitors, "the scene of constant and genial hospitality." This is the testimony of Professor Samuel G. Brown who knew intimately the Olcott family and saw the Squire's generous friendship and loyalty manifested toward his own mother, the widow of the heroic President Francis Brown who had literally laid down his life for the College. In those dark days when President Brown, Olcott and Webster were fighting with such courage and loyalty for the "small college," the President, worn with anxiety and illness must often, as he passed on his way from home to the meeting-house, have stepped into the Olcott home to consult with the friend who was not merely the Treasurer and the lawyer who had brought the suit in the College Case but also a man of affairs, an experienced and influential politician (in 1819 a member of the Legislature), not merely loyal, but shrewd, courageous, imperturbable and generous,- the sort of man with whom the burdened President would inevitably share his burden. Squire Olcott's loyalty and faith deserve loyal remembrance. He not only subscribed money and gave his time and energy, but also personally pledged the bulk of the sum which guaranteed the college officers their salaries, should the College lose its case. His imperturbability is illustrated by his attitude when a hurrying messenger on horseback brought him the news that for the third time his dam at Olcott Falls had been carried away. "Well, I don't see how I can help it," he replied and quietly renewed his reading of a play of Shakespeare to his family. His deep religious feeling, where again he was in sympathy with President Brown, is strikingly illustrated by his written confession of faith, when this shrewd and polished man of affairs, at forty-five years of age joined the church, the year the College won its case. Twelve of his own immediate family became members; and in all no fewer than thirty of those connected with the house united with the adjoining church.

All of Squire Olcott's eight children entered the Dartmouth fellowship. Three sons graduated, "Ned" '25 and William Olcott, '27, being in college with Salmon P. Chase, '26. Chase, later Lincoln's Secretary of Treasury and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, in his youthful letters, writes familiarly about the Olcott boys and the family affairs and is known to have been at the house.

Each of the Squire's five daughters married a Darmouth lawyer. Daughters and granddaughters of Dartmouth men, unable to take a degree from the family alma mater, they carried on the academic genealogy by becoming mothers and grandmothers of Dartmouth men, certainly winning their place in the Dartmouth fellowship, by degrees. The eldest daughter married Joseph Bell (1807), noted later as a partner of the Hanover-born Henry F. Durant, founder of Wellesley. Helen Olcott became the charming and helpful wife of Dartmouth's finest scholar and advocate, Rufus Choate, '19. The other daughters married William T. Heydock, classmate of Choate, and nephew of Webster with whom he studied law; Charles E. Thompson, '28; and the cultivated, widely read Squire Duncan '30, a Hanover personage picturesquely described in Professor Bartlett's Dartmouth Bookof Remembrance. Two of these daughters of Olcott became mothers of sons of the fourth generation to hold Dartmouth degrees. One of these greatgrandsons of Trustee Peter Olcott, Joseph Mills Bell, '44, not content with being Rufus Choate's nephew and partner-in-law, became his son-in-law, marrying that favorite daughter Helen Choate Bell (long "a centre of all that was finest and best in the social and intellectual life of Boston"), to whom Choate remarked at the opera: "interpret to me the libretto lest I dilate with the wrong emotion."

The romance of the house clusters about Rufus Choate and Helen Olcott. The handsome, brilliant, haggard valedictorian of 1819 thought of dying, but returned to "endeared Hanover" to love and live, as tutor. nineteen year old Rufus Choate with his dark eyes ablaze beneath his tangled black curls, and Helen at sixteen (and always) "very lovely and charming," make a pleasant picture in the traditional courtship in the large and fair garden where Butterfield Hall now encumbers the ground. Credible the tradition is. Rufus would quite naturally have preferred a bench with Helen in the garden to being brought before the bar of the house. Even the most famous advocate of his day would have hesitated to use his powers before a houseparty of five sisters, three brothers, and other talesmen. Fortunately we do not have to depend upon tradition or imagination. From witnesses inconvenient for the lovers but useful for historic purposes, we know that Rufus prolonged his wooing like his study until late at night, when the inevitable small boy should have been in bed but was not. One of these Hanover boys of 1819-20, later an entirely respectable Mayor of Brooklyn, related the incident in presence of Choate's friend, Professor E. D. Sanborn, who wrote it down for publication in Neilson's Memories ofChoate:

"The old home where the young tutor and the beautiful girl who won his heart met to enjoy the passing hours and make their plans for future years was peculiarly dear to him. The students knew that their teacher often passed some of the small hours of the night in Mr. Olcott's parlor. Mr. Smith and a few of his associates used to serenade the young couple occasionally. One night they took their stand on the deck of the steeple near the house." "In the morning Mr. Choate sent for Mr. Smith, whose voice he had recognized, and admonished him to select a humbler stand and a more reasonable hour for his musical exhibitions."

No wonder Choate speaks of his life in "endeared Hanover" as "so exquisitely happy," or that he loved to return to it with the wife who contributed so much to his successful life. In witness of one of her visits, there still remains her name, "Helen O. Choate, Boston" cut into an ancient window pane of the southwest chamber. Her name with that of her sisters appears also on the window of the east parlor where, according to Dr. Leeds, she was married. Cutting names on window pains appears to have been a favorite indoor sport of Olcotts, Bells, Thompsons, Longs, Uphams and Choates, a dozen of whose names still are recognizable on the bulbous glass of long ago. Apparently Rufus Choate wisely refrained from attempting his hieroglyphics on glass; but it would be a wise handwriting expert who could demonstrate that some illegible scratches are not the undecipherable sign manual of the only man who could read Choate's writing!

Choate and Webster came together in various ways and probably at the Olcott house, during Webster's attendance at the Commencement of 1819, following the Supreme Court's decision in favor of the College. Choate in his Commencement valedictory paid tribute to President Brown and Webster, and a very deft compliment to the latter by cleverly adapting the figure of alma mater being stabbed "in her robes" from Webster's peroration before the Supreme Court. Webster would almost inevitably have followed the custom of the day and been in the audience especially since one nephew William T. Haddock was one of the speakers and another nephew Charles B. Haddock received his A.M. and was announced as elected to a professorship. Moreover the concluding prayer was offered by Roswell Shurtleff, with whom Webster had spent his first night in the Olcott house and around whom the Dartmouth College Case had at first centered.

That Choate and Webster were "at an evening party" together during this Commencement we know from Choate's own keen recollection of Webster's conversation there. The natural place for such a party would have been at Squire Olcott's, especially in view of the illness of President Brown. Moreover Webster in any case would have naturally paid his call on the Squire. It was not only customary in general for visitors to do so, but Webster had been accustomed to make such calls. His charmingly frank letters to old college friends show a keen interest in the homes and people of "the charming village," and the habit of visiting them during his frequent visits to "Old Han," for this was his ninth since graduation. Furthermore, it was especially likely that he should revisit the scene of his first night in college; and almost inevitable that he should call upon the treasurer who had brought the suit over which the College was rejoicing. Webster's nephew, William T. Haddock, in Choate's class, was to marry one of the Squire's daughters. Choate would certainly have been at Helen's, would have known of Webster's movements through Haddock, and in view of his already keen admiration of Webster would have naturally sought the opportunity of meeting him there. Whether the two lifelong friends met at the Olcott house remains a matter of probability rather than proof. Unfortunately no trace can be found of what must have been the large correspondence between the two life long friends. The details of their meeting save for Choate's recollection of Websters conversation "at an evening party" have perished; but "the friendship of scholars, grown out of unanimity of high and honorable pursuits," described by the youthful valedictorian of 1819 was imperishably recorded in Choate's classic Eulogy of Webster delivered in 1853 from the same platform whence he could see the adjoining house which had sheltered both Webster and himself.

When Choate returned for his LL.D. in 1845 and to deliver the Webster Eulogy in 1853, he would have found the old home, where he had paid tuition to the treasurer and court to his daughter, occupied presumably by his own brotherin-law, Squire Duncan '30, perennial and picturesque Commencement Marshall, whose resourcefulness saved the day in the face of the mob trying to force an entrance into the meeting house to hear Choate's Eulogy. Squire Duncan, who was associated with Choate in the corporation that took over Squire Olcott's mills and locks at Olcott Falls (now Wilder, Vt.), occupied the house for some years between the death of the old Squire, 1845, and that of his daughter, Squire Duncan's wife, 1854. The generous hospitality of parsons, professors and squires was kept up by Clement Long, Professor of Philosophy, 1854-61, who had been in college with Salmon P. Chase, the Olcott boys, and with Thompson '28 and Squire Duncan '30, who married Olcott girls.

The traditional hospitality and Dartmouth loyalty were kept up for another half century by four pastors of the adjoining church. Reverend John Richards belongs to the Dartmouth fellowship by reason of his eighteen-year pastorate of what was commonly called the "college church;" by his Dartmouth degree of D.D.; by his sending his son John Richards, Jr., '51 through Dartmouth; and by his keen interest in the Dartmouth alumni, manifested in his work on the triennial catalogue of 1858 and his project for the Alumni Sketches, carried to completion by Chapman.

Dr. Richards was followed in the pastorate by the scholarly, beloved Dr. S. P. Leeds, a D.D. of Dartmouth and identified with its interests as either pastor of the college church or member of the Board of College Preachers, for fifty years. Having no child of his own, Dr. Leeds followed the tradition of the house by making a home for two Dartmouth men, adopting one and giving him his own name. This Edward Leeds Gulick, '83, returned to teach in Dartmouth, and live again in the old home then known as the "Leeds house." His son Edward Leeds Gulick, Jr., graduated in 1913. His daughter Carolyn, the ninth daughter of Dartmouth to follow the good example of Abigail Wheelock, married Chauncey Hulbert, '15, a direct descendant in the sixth generation of Eleazar Wheelock, thus completing the circle from Wheelock to Wheelock.

The fifth and sixth pastors of the adjoining church were Ambrose White Vernon, D.D. of Dartmouth, and Professor of Biblical Literature on the restored Phillips Foundation, originally held by Ripley, builder of the house; and Robert Falconer, '05.

So faithfully was the tradition of hospitality carried out by the Leeds family, that even in the Doctor's absence in Europe, when the mischievous undergraduate literary societies elected Walt Whitman as Commencement Poet, vainly hoping the faculty would make objections, the gentle Mrs. Leeds stood to the tradition and entertained the good gray poet whom the college people had thought fit to invite. The pastor's wife played the game—the ancient Dartmouth game of academic freedom. She repo'rted she did not find Whitman troublesomely peculiar in any way. One wonders if there was a twinkle in the eye of both at his departure, when the burly poet with his somewhat Wild West appearance presented the demure wife of a village pastor with a copy of his poem, "As a Strohg Bird on Pinions Free." "It is a curious scene here as I write," said Whitman in a letter from the Leeds House. "A beautiful New England village 150 years old, large houses and gardens and great elms, plenty of hills everything comfortable." "As I write a party are playing baseball on a large green in front of the house." This vizualizes for us the picture seen by so many of those famous guests who "looked out through the windows of this house," as Dr. Leeds used to put it.

Dr. Leeds was a man of such accurate scholarship and cautious mental habit, that one can place unusual trust in what he carefully kept in mind as to the houseguests. Fortunately his remembrance has been preserved through a written statement kindly furnished by Mrs. Fanny Huntington Chase (widow of the late College Treasurer, Charles P. Chase) Hanover-born, and noted for her tenacious memory.

"You ask me to tell you again the names of the people whom I once heard Dr. Leeds speak of as having looked out through the windows of his house. The list he gave was longer than I can give you now, for I shall only put down those names that I am absolutely sure that I remember correctly. These are: R. W. Emerson, H. W. Longfellow, James T. Fields, Dr. O. W. Holmes, E. E. Hale, Julia Ward Howe, W. M. Evarts, P. B. Shillaber ["Mrs. Partington"], Chief Justice Chase, Gen. Sherman, J. G. Saxe.

"The date when this list was given I cannot tell, but it was previous to 1900. It was during a call at our home when Dr. Leeds and my father were recalling events and people of former days.

"I am sorry I have not something more important to tell you of by far the most interesting house in our village.

Very sincerely yours, Fanny H. Chase.

Hanover, N. H., October 10, 1923."

Mrs. Chase's letter gives us documentary confirmation of the statement of Professor Charles F. Bradley '73 "The house has sheltered a great part of the distinguished men who have come to Hanover to lecture. In fact it is often said that in no building north of Boston have so many illustrious men been entertained."

To the President and the Trustees in their wisdom as successors to the original grantors of the "one acre of land north of the green," we look for assurance of the preservation of this "simple, dignified colonial house typifying the character of those who have inhabited it," and enshrining the imponderables of a pioneer college that are beyond price.

Dr. Tucker, in a personal letter expressing his appreciation of the attempt to "reorganize the history of the Leeds house," and "restore the house to its rightful place in our village and college life," and of the Trustees' magnanimous response in rescinding an earlier vote to demolish the house, concludes with this wish:

"I hope and believe that the Trustees of the College will not only keep the house but place it where it will be of present use. I have at different times given a good deal of thought to its incorporation with the expansion of the College, but I make no suggestion now as I do not know in detail the present scheme of building."

None of us would desire to see this house or anything else stand in the way of general plans of development of the College. What may fairly be pointed out however is that a wise plan of development includes background as well as foreground, and is not a matter of architecture alone. Once the value of the house is realized and a positive decision reached that a place must be found for its "incorporation with the expansion of the College," then the modern architect and engineer and landscape gardner will face and solve the challenge.

The challenge runs something like this. Since Dartmouth burned, "Sanborn tottered down the lane to the cemetery," and the Proctor, Brown and Hubbard houses were demolished, not a single college building older than Thornton and Wentworth remains facing the campus. Is a colonial college, planning for colonial buildings, going to sacrifice its one colonial structure on the campus?

Somewhere within its original "one acre north of the green," whether on its present site, or nestled closer to the white meeting house, or centered before the proposed library building—possibly lowered from its present six feet above the. street level, attractively surrounded by shrubs and flowers, suggesting the old garden, the scene of Choate's wooing of Helen Olcott—this shelter of literature and scholarship, "somewhat back from the village street," would form an inspiring approach to a library. In a country village, "with its houses scattered along the grassy margin of its streets," the library of a colonial college does not have to imitate the crowded city and elbow out of its way a building which once housed the authors whose books are on the library shelves.

Properly restored (with its modern woodshed removed), furnished with appropriate colonial furniture and portraits of the men, and women it has sheltered, perhaps used as an historical museum and a modern centre of hospitality, it would be not merely a reminder of the past but an inspiration to the future.

On land granted by the founder of Dartmouth, built by a member of its first graduating class, as a home for himself and .the daughter and four grandchildren of Eleazar Wheelock, the first of a procession of no fewer than thirty-six Dartmouth sons and daughters, among them two village squires, three trustees, four professors, six pastors of the adjoining church ("gathered by Eleazar Wheelock"), nine daughters of Dartmouth and wives and mothers of Dartmouth men, and twenty-seven alumni including her greatest statesman and finest scholar, the only college building of Webster's and Choate's day still facing the campus; the scene of hospitality to a President, Chief Justice, and General of the nation, the most famous statesmen,

lawyers, orators, poets, essayists, and humorists of America,—this house of remembrance is invaluable, irreplaceable. Other institutions will probably always be richer in material wealth. How many colleges can compete with this historic asset, the visible embodiment of what college and nation have fought to maintain since colonial days? An historic college built upon genuine traditions and abiding ideals must preserve their historic abiding place. That none of the alternatives so far proposed for the house appears satisfactory does not logically lead to its demolition or removal. Time is a wonderful solvent. It may show the College how to retain its inheritance. Meanwhile an historic college cannot afford to throw away a real colonial structure to get an unobstructive view of an imitation. There must still be parking space on the Dartmouth campus for its one eighteenth century college building.

As long as the house stands, there is a possibility of some satisfactory solution, some right way and place for preservation. Town planning and collegeplanning on long lines are yet in their infancy, and much remains to be learned. If the house is once destroyed, the chance to make use of any later and better wisdom for "its incorporation into the expansion of the College" is gone forever, the loss irrevocable. Certainly the fullest possible fire protection should be provided at once.

The Ripley-Olcott-Leeds house, coeval with the College, older than the constitution of the United States, comes down to us embodying a century and a half of college and national ideals. If we should sacrifice this home of romance, courage, loyalty, faith in God and man, this scene of hospitality to literature, scholarship, and statesmanship, later generations would rightly condemn our lack of loyalty and vision, our failure to preserve for them the trust which the founders and refounders of Dartmouth have handed on to us.

Mills Olcott, Treasurer and Trustee

Mrs. Helen Olcott Choate Courtesy of Miss Alice Van Vechten Brown

A very early picture of Webster Given by Mr. Webster to his first wife and by her to a niece, Mis. Pierce

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE OLD SONGS

April 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleTo what has been written

April 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1925 -

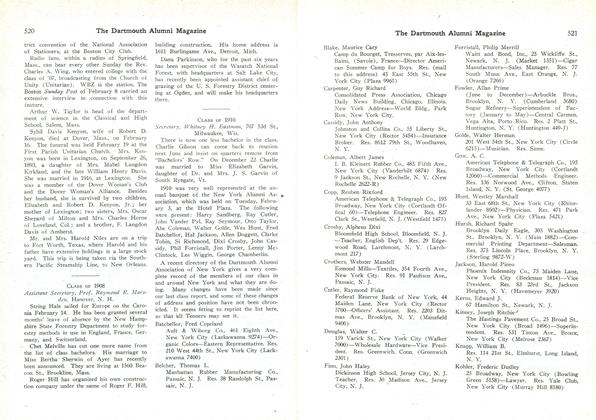

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

April 1925 By Ralph Sanborn -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1925 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1925 By Whitney H. Eastman