There appeared in The Boston EveningTranscript of Sept. 30, following the death in Hanover of President-Emeritus Tucker, an appreciation of Dartmouth's great president written in 191£ by Professor C. F. Richardson, which the Transcript graciously permits THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE to reprint. Professor Charles Francis Richardson, affectionately called "Clothespins" by many Dartmouth generations was Winkley Professor of Anglo Saxon and English Language and Literature at Dartmouth from 1882 to 1911. He was a graduate of the class of 1871. Professor Richardson died in 1913.

William Jewett Tucker: An Appreciation By C. F. RICHARDSON

Any successful promoter of the world's good motions is pretty sure to be characterized by many unlikenesses to other men. Where he does not stand above average humanity he stands ahead of it, or on the side of it, in such ways as to mark him out. Such severence occasionally becomes a pose, but never in the case of an individuality like that of William Jewett Tucker, president of Dartmouth College from 1893 to 1909. If I were to try to characterize Dr. Tucker as man, preacher, teacher, college president and author, I would do it in just two words, simplicity and sincerity.

Of Dr. Tucker's education at Dartmouth and Andover I cannot speak with any knowledge, save that the Dartmouth of '6l was certainly as straightforward a school as in my later time, and even more limited in what we now call the necessities of existence. His Manchester pastorate is still affectionately remembered, as is that in New York, where, in 1875, he succeeded Dr. William Adams in the pulpit later occupied by Dr. Charles H. Parkhurst. But I think that those who best knew Dr. Tucker in Manchester and New York are the ones who feel that he came to his larger self in Andover and his largest in Hanover. I heard him preach one evening in Madison Square Church, but I am ashamed to say that I retain no memory of either matter or manner, which is my fault, not his.

At Andover

Going from the metropolis to Andover Theological Seminary in 1879, as professor of homiletics, Dr. Tucker was' neither young nor old, and carried to the time-honored school of the prophets just what it needed: spirituality, earnestness, experience and a liberality that recognized the historic groundwork of conservatism. At Andover, Dr. Tucker, while loyally supporting Egbert G. Smith, George Harris and John Wesley Churchill in their liberalism, and meanwhile giving sound instruction in his chair, reached out farther than any other of the professors in two ways: First in his constant preaching in vacant Congregational pulpits in eastern New England—afterwards a great asset, because of the power of his personality, in his building up Dartmouth; and, second, in his devotion to practical sociology, a devotion visible both in the pages of the Andover Review and in the work of the Andover House Settlement in Boston. During his residence at the seminary he was not only the best-esteemed Congregational preacher in Massachusetts, but also a wholesome force in applied philanthropy at that time rising to new prominence.

Then, in 1892, came his first call to the presidency of Dartmouth College, which he declined in a published letter, because of his deep sense of obligation to Andover, and to the collateral undertakings growing out of his seminary connection. Furthermore, he was comfortably housed, happy in his work and associates, and near many churches in which, as I have said, he was a frequent and most "acceptable"—as the old "professors of Christianity" used to say—preacher. But the call was imperatively renewed, and the other trustees of the college, of whose body Dr. Tucker was a valued member, reelected him; and as Trustee Alonzo H. Quint told me at the time, threw the whole responsibility of the standing or falling institution on his shoulders. This responsibility, thus renewed, Dr. Tucker felt that he could not refuse; or, to quote him also in a contemporaneous remark, he did not feel that he had a right to stand and see the whole structure tumble on our heads and his, if there was anything he could do to help it. So, to the vast advantage of Dartmouth College, he assumed its presidency in 1893.

"Too Much of a Gentleman"

The simplicity of President Tucker's inauguration strikingly illustrates the development of college ceremonial during the twenty years since. Just one other college president was present, and even he came, not as formal representative, but as a personal friend. I cannot say that he brightened the occasion, which fact may have been due to his feeling, as expressed to a friend of his and mine, that Dr. Tucker was "too much of a gentleman" to be president of the Dartmouth College of that day.

Truth to tell, not all omens were auspicious. Dartmouth was certainly among the foremost of American institutions of learning; it had an honorable history; a hard-working and, as Dr. Tucker has always said, entirely competent faculty; a manly set of students, and a body of alumni forcible in affairs. But the effects of a violent controversy regarding the policy of the outgoing president were still disastrously felt. Into the rights and wrongs of that controversy I do not need to enter at this late day; but it had alienated the sympathetic interest of a considerable number of the alumni, and some ot the outgoing graduates had departed in a mood either indifferent or hostile. The buildingh Save the chapel, library and Congregational Church, were not in modern condition. There was "° physical laboratory worthy of the name; no biological laboratory, no commons and no steam heating plant, and the dormitories were in the state_ of fifty years before. The average alumnus will say that when I add that there was no athletic field, save the free-to-all college common, the depth of admitted degradation Is reached ; while the hygienist and insurance man will alike be interested in the remark that there was not a bathtub or even a drop of running water in_ any academic building. The entering classes, in an institution which used to be the numerical equal of Harvard or Yale, had fallen below those in other country colleges like Amherst or Williams. The year before Dr. Tucker s arrival the incoming freshmen numbered about fifty-five, plus some twenty in the then separate Chandler scientific department, in which the entrance requirements were not of collegiate grade. The same year 13S entered Amherst. Clearly Dr. Tucker had enough to do, even admitting the excellence of the faculty and adding the fact that it had just thoroughly and intelligently revised the curriculum.

Circumstances therefore, almost compelled the new president to begin with externals. Fortunately he had an accidental "starter" in an immediately previous gift of some $175,000 for the erection and maintenance of a building for the departments of geology, biology and sociology. This structure, erected at a cost of a third less than would be necessary today, gave needed facilities and became a visible and salutary argument for other improvements of a similar sort. Incidentally, it illustrated Dr. Tucker's capacity for looking far ahead. We must not, he said, continue to drop buildings around at random; so then and there he forsaw and began to develop all the later architectural enlargements of the college; three sides ot a quadrangle north of the Commons ; a quadrangle east of the old row; a line of buildings on a developed terrace northeast of Rollins Chapel; a second fine quadrangle west of the campus; and last of all, a slight return to President Smith's old scheme of two rows east of Reed Hall, on both sidfes of the street.

All this growth absolutely depended upon the construction, largely under Dr. Tucker's influence, of the Hanover waterworks. At this point it is proper to say that Dr. Tucker regrets that he was obliged to leave the erection of a new library building to his successor—the old one, though dating back no farther than 1885, having long been crammed to the walls, the cellar and the roof. "Had I been able to go on for half a dozen years longer," he once said to me, 'I would have got a new library bv hook or by crook."

Not a Good Money-Getter

By the way,the vlsltor to Dartmouth who noted the difference between architecture in 189 J and m 1907 was rather surprised to read, in Dr. Tucker's letter of resignation of that year that he did not regard himself as a good money-getter. "He'll be an expensive man for you, was the remark of one rather mordant trustee on Dr. Tucker's election. Fortunately he was in the best sense; for even where his dreams had seemed daring, their wisdom was borne out by events, and by loyal support all along the line.

Such a man, it goes without saying-, though the start he instantly and perseveringly set himself to the task of giving Dartmouth decent quarters m which to do collegiate business, was tar too wise to deem the box more important than the treasure. At the beginning of his administration, various vexatious but imperative problems confronted him. The State Agricultural College had, fortunately for it and for Dartmouth, been removed to Durham; but the Chandler scientific department—a subject of sharp contention in President Bartlett's timeseriously needed readjustment. Dr. Tucker immediately said that either it must be given an adequate separate equipment and endorsement, as in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology or the Sheffield School at Yale or else frankly be incorporated, with certain changes, in the college proper, as has been done with similar departments at Harvard and Princeton. Here as m all like problems, Dr. Tucker had the matter thoroughly "thrashed out" by committees of the trustees and of the faculty, with the result that the second alternative was chosen. Committees, temporary or permanent, were also set up for all sorts of administrative work, and on them Dr. Tucker always largely relied. When he came, college discipline, or even such a thing as the purchase of individual books for the library, was "considered" in open faculty* with an enormous waste of time. That there was some subsequent waste under the committee system I can sadly testify, after long experience; once after the "horning" of a professor, the then committee on discipline" (now the committee on administration,) held seventeen sessions. But Dr. Tucker always made it a cardinal principle to give every really interested person, instructor _or student, ample time to state his whote view, if thus light might be secured In this particular instance the end justified the means; for a frank withdrawal of probable penalty, to be visited on nearly an entire class, led to. a development of student self-reliance, and a confidence in Dr. Tucker as an administrator.

Always Perfectly Fair

Every student always felt in the president's office, or in a committee interview, or in the occasional public announcements of statements of policy which he soon inaugurated, that Dr. Tucker was perfectly fair, according to his lights. That anybody, student or teacher, always agreed with him, or that he always agreed with anybody, would be a ridiculous claim; but even in some pretty sharp controversies—of which a belated one concerning the conditions of appointment or promotion of instructors was the most acrid—no one questioned his integrity or sincerity. A college faculty may be (as Woodrow Wilson said in my hearing, in a delightfully frank address on "The Art of Being a College President," at the inauguration of President Richmond of Union) "as sensitive as a church choir," but it knows, as quickly as the student body knows, when it is in the presence of a gentleman and a man of ideas. On the whole, the collegiate instructor shoots more barbs sidewise and downward than upward. I think that the general testimony of the Dartmouth faculty would be that they never knew a man more nearly free from pettiness, jealousy, self-assertion, or the too frequent presidential desire to say "L'etat, c'est moi."

This sincerity and candor, back of great constructive power, were equally apparent to the alumni, as he addressed them up and down the land or met them otherwise. By the way, I think one "crumb of comfort"—the figure is apt— in his mind, when he laid aside his official duties, was that the gastronomic part of his winter trips was but a patient memory.

Behind the architecture and the curriculum stood and stands William Jewett Tucker, the man; and his greatest achievement for Dartmouth, after all, must forever be declared to be the influence of his ten-minute chapel-talks at Sunday vespers. Here, in a union of spirituality, common sense, and pithiness, week after week and year after year, he struck straight home to the moral element in the undergraduate mind, so that few hearers failed eagerly to follow his words, and few have entirely lost their influence in later years. I have heard his style called hard or unduly compact, but it is the hammered metal that lasts longest and is valued most.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1926 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1926 -

Article

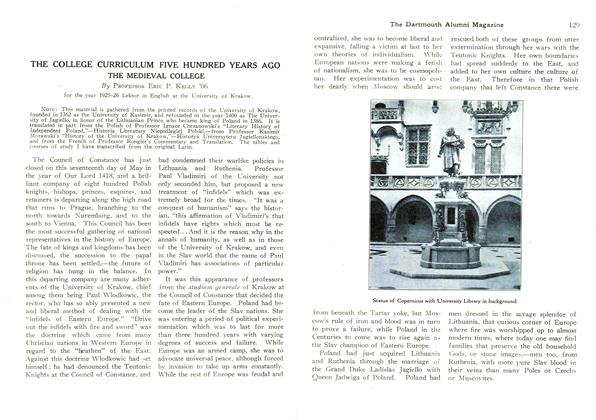

ArticleTHE COLLEGE CURRICULUM FIVE HUNDRED YEARS AGO THE MEDIEVAL COLLEGE

December 1926 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticlePHYSICAL FITNESS WORK AT DARTMOUTH 1925-26

December 1926 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Article

ArticleWHY THEY DON'T ATTEND MASS MEETINGS

December 1926 By Harry R. Wellman '07 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEETS IN BOSTON

December 1926