THE COLLEGE CURRICULUM FIVE HUNDRED YEARS AGO THE MEDIEVAL COLLEGE

DECEMBER 1926 Professor Eric P. Kelly '06THE COLLEGE CURRICULUM FIVE HUNDRED YEARS AGO THE MEDIEVAL COLLEGE Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 DECEMBER 1926

for the year 1925-26 Lektor in English at the University of Krakow.

NOTE: This material is gathered from the printed records of the University of Krakow, founded in 1362 as the University of Kasimir, and refounded in the year 1400 as The University of Jagiello, in honor of the Lithuanian Prince who became king of Poland in 1386. It is translated in part from the Polish of Professor Ignace Chrzanowski's "Literary History of Independent Poland,"—Historia Literatury Niepodleglej Polski,—from Professor Kasimir Morawski's "History of the University of Krakow,"—Historya Universytetu Jagiellonskiego, and from the French of Professor Rongier's Commentary and Translation. The tables and courses of study I have transcribed from the original Latin.

The Council of Constance has just closed on this seventeenth day of May in the year of Our Lord 1418, and a brilliant company of eight hundred Polish knights, bishops, princes, esquires, and retainers is departing along the high road that runs to Prague, branching to the north towards Nuremburg, and to the south to Vienna. This Council has been the most successful gathering of national representatives in the history of Europe. The fate of kings and kingdoms has been discussed, the succession to the papal throne has been settled,—the future of religion has hung in the balance. In this departing company are many adherents of the University of Krakow, chief among them being Paul Wlodkowic, the rector, who has so ably presented a new and liberal method of dealing with the "infidels of Eastern Europe." "Drive out the infidels with fire and sword" was the doctrine which came from many Christian nations in Western Europe in regard to the "hjeathen" of the East. Against this doctrine Wlodkowic had set himself; he had denounced the Teutonic Knights at the Council of Constance, and had condemned their warlike policies in Lithuania and Ruthenia. Professor Paul Vladimiri of the University not only seconded him, but proposed a newtreatment of "infidels" which was extremely broad for the times. "It was a conquest of humanism" says the historian, "this affirmation of Vladimiri's that infidels have rights which must be respected.. .And it is the reason why in the annals of humanity, as well as in those of the University of Krakow, and even in the Slav world that the name of Paul Vladimiri has associations of particular power."

It was this appearance of professors from the stndium generate of Krakow at the Council of Constance that decided the fate of Eastern Europe. Poland had become the leader of the Slav nations. She was entering a period of political experimentation which was to last for more than three hundred years with varying degrees of success and failure. While Europe was an armed camp, she was to advocate universal peace, although forced by invasion to take up arms constantly. While the rest of Europe was feudal and centralized, she was to become liberal and expansive, falling a victim at last to her own theories of individualism. While European nations were making a fetish of nationalism, she was to be cosmopolitan. Her experimentation was to cost her dearly when Moscow should arise from beneath the Tartar yoke, but Moscow s rule of iron and blood was in turn to prove a failure, while Poland in the Centuries to come was to rise again as the Slav champion of Eastern Europe.

Poland had just acquired Lithuania and Ruthenia through the marriage of the Grand Duke Ladislas Jagiello with Queen Jadwiga of Poland. Poland had rescued both of these groups from utter extermination through her wars with the Teutonic Knights. Her own boundaries had spread suddenly to the East, and added to her own culture the culture of the East. Therefore in that Polish company that left Constance there were

men dressed in the savage splendor of .Lithuania, that curious corner of Europe where fire was worshipped up to almost modern times, where today one may find families that preserve the old household Gods, or stone images,—men too, from Ruthenia, with more pure Slav blood in their veins than many Poles or Czechs or Muscovites.

Behind all this activity on the part of the Polish delegation to Constance was the influence of a woman! There is to me no more pleasing personality in all history than Queen Jadwiga, the matron saint of Poland. She was the daughter of' King Louis of Hungary, a king perhaps "of shreds and patches," a king who loved Hungary more than he did Poland, but his daughter inherited through lier mother the blood of the Piasts, the first great ruling dynasty in Poland. She lived a life that was one long self-sacrifice to her country, an example approached only by Tadeusz Kosciuszko four hundred years later when he took his famous oath to uphold the honor and defend the well-being of the Polish people,—an oath taken in that very marketplace, the Krakow Rynek, through which Queen Jadwiga had ridden in triumph after her marriage to Jagiello.

She had not wished such a marriage. In fact her affections lay elsewhere. But she gave up her happiness for her country's good, and-married Ladislas Jagiello in order that Poland and Lithuania might be united, even as England and Scotland were united later when James came to the English throne. Her jewels she gave to the University of Krakow, chartered in 1347 and founded in 1362 by Kasitnir the Great, when that king sought to increase his fame by establishing such a center of learning as Paris, Prague, or Bologna, the three universities then dominating intellectual life in Central and Eastern Europe. The old Ruthenian university at Kiev had been destroyed by the Tartars,—a university in Hungary had not been successful. Therefore the kine had an excellent chance to establish a center of learning to be frequented by all1 the Slavs who belonged to western rather than to eastern civilization. The highest school in Krakow at that time was the Cathedral School located on the Wawel or central hill of the town, where stood the Cathedral and the fortified castle. Kasimir made plans at first for a school in the Kasimierz, a walled city adjoining Krakow, which the king had built and set aside for the Jewish exiles then pouring into Poland from many other countries where they were being persecuted.

The university in the Kasimierz prospered but little however. It was not until the year 1400 after the death of Queen Jadwiga that her jewels were made the financial basis of a rebuilt university. A new site was located in St. Ann's Street where the university library stands today. The first class entered with 205 students. The faculties included 11 professors and a number of assistants. The students were allowed some choice in the selection of their masters. In addition to certain civil privileges granted these students, there was appointed a money-changer who would lend money to needy students and not collect more than one grosz per mark each month. This was equivalent to a rate of about S per cent a month. Vienna, Heidelberg, and Cologne had all established colleges soon after the founding of the university at Krakow, and these with Prague, Paris, Padua, Bologna, and Krakow, were among the 37 universities represented at the council of Constance.

Jagiello appeared at the opening of the new building and read his decree, or had it read by a scribe, as follows: "In order that the doctors, the masters, the candidates for masters' degrees, the bachelors, the students of the University of Krakow, can freely and comfortably devote themselves to their studies, lessons and other exercises, WE designate OUR HOUSE located on St. Ann's street, to serve for a headquarters (logis) for the Masters and for the assembly of students; such house we incorporate

forever with the University as the property of-the doctors, masters, and members of the college."

The schools of Theology and the Septem Artes were together. The Law faculty was in a separate building, procured at first through lease on Grodzka Street. The first enrolled student was Mathias Johannis de Tarnow (Tarnowski),—his records have been preserved. In 1406 was graduated Zbigniew Olesnicki, the most powerful personality in Poland in the Fifteenth Century.

A student who entered the university was at first enrolled in the College of Arts. He was fed upon Aristotle,—in large doses. When the Grammarians were in the ascendant he was crammed with grammar, though some attention was given to logic, arithmetic, geometry, music, rhetoric, and astronomy (curiously mixed with astrology). When Grammar was dethroned as the Queen of the Arts a few years later, logic was the subject upon which he was most drilled. Having finished a study of the arts, the student chose one of the higher subjects for study. If he chose Theology, he entered at once the courses presided over by the Ecclesiastical authorities. If he chose law, he had a long gamut of Roman and Canon law to run. The Roman lawwas chiefly Justinian, and Canon law a study of decretals with a "nova jura" or modern church decisions. The teachings throughout the whole university were carried on in Latin, since Latin was the tongue of the Church, of public life, of science, of the great and small international councils. The university was supported by the original gift of Queen Jadwiga, grants from the nobles and merchants (one of whom was enormously wealthy and once entertained six kings), pensions from the church, and an income from the salt mines of Wieliczka, those ancient mines where there is an underground city of crystal, a church, a lake, and many curious antiquities.

The arts students were fed also upon a certain Boetius, a writer of the Fourth Century, whose book, according to Morawski, "maintained a certain liaison between the modern age and classical antiquity, of which it was in certain ways the swan song." His translations and his commentaries upon the logic of Aristotle were the pride of the scholastics. Though but little studied today, he had a long and popular regime. A poem of Alanus, "de planctu naturae," written by a master at the University of Paris in the Twelfth Century was also an authority at that time in the fields of philosophv and poetry. There were available also the prose writings of Valerius Maximus, the poets Horace, Terence, Ovid, Virgil, Martial, and others. Cicero and Seneca were not wholly neglected but it is doubtful if each student went through the whole list mentioned above. Just how thorough the teaching of Latin became is something of a question at this day and age. Most students were efficient in the use of it, but men not proficient in it seemed to rise to high positions, sometimes, and others clearly did as little of it as possible,—the desire was to write it and speak it, no matter how poorly or thinly.

As in universities and colleges everywhere, in all times, there was an immediate conflict between the bread-winning curriculum and the pure arts curriculum. Goethe's cultural cow which was to supply the milk and money of daily life was in demand in some quarters. There is something which has a familiar sound in this paragraph which I translate from Morawski:

"And it is certain that there spread about in these foyers of culture a certain idealistic atmosphere, despite all the defects of the university, despite the suggestion of petrification in the curriculum of that day, and the absence of that mental unrest which in our time the progress of learning and the thirst for culture has introduced into life. Human thought was active there in the university, in a detachment from reality,—it cultivated art, and even the shadow of art, for its own sake; it indulged in 'superfluitas meditationis' as contemporaries accused. Words fell to the students from the heights of professorial chairs, and the disciples who received them, did not dream of turning them into daily bread....

There was above all the studies of the faculty of arts, which breathed this detachment from the friction of everyday life; for if a study of the decretals (canon law) rendered the student eligible to high and powerful positions,—if Medicine prepared the student for a practical life,—on the contrary the ideas gathered in study under the faculty of arts could not find application in the life of the time, nor could they procure riches. Once in possession of his diploma, the master of arts had before him an existence without profit, and in most cases charged with heavy obligations. Jerome of Prague in speaking at the council of Constance of the studies at Prague, said: "After having' obtained a grade at the faculty of arts, the Czech student, if he has not other resources, sees himself forced to go into the villages or small towns and take there the direction of the local schools in order to assure himself of a morsel of bread." This remark was applicable in all the universities of Europe.

I am leaving the rest of the story to Professor Chrzanowski of the University of Krakow who tells in his popular History the story of the early curriculum.

In the Fifteenth Century the Academy of Krakow developed brilliantly its students were not Poles alone, but even foreigners, Germans, Czechs, Swiss, Hungarians. While devoting itself above all to learning it was not unmindful of other matters of broad interest ; its professors took part in the deliberations of general councils at Constance and Basle where they drew much attention to themselves by reason-of their erudition: at the deliberations in Constance the rector of the Academy, Paul Wlodkowic eloquently and successfully defended Polish affairs against the contemptible intrigues of the Teutonic Knights, who claimed for themselves rights of dominion over the newly converted Lithuanians.

Devoting itself like all schools of the Middle Ages to the Latin tongue, equally in lectures and writing, the Academy did concern itself with the tongue of the mother-country, and one of its rectors, Jacob Parkosz wrote a Latin treatise and Polish verses in Polish orthographv which he tried to make uniform. The academy became notable throughout the whole civilized world for its noted theologians, its mathematicians, and its astronomers, the most famous of whom was Wojciech of Brudzewa; in attendance upon his lectures was Mikolaj Kopernik (Copernicus). Most zealously indeed the Academy cultivated the so-called Scholasticism.

By this term scholasticism is meant the teaching of the Middle Ages,—its main purpose was to establish the truth of religious dogma; and the whole teaching of the church was to strengthen its arguments. This teaching brought out nothing new, nor could it,—there was no desire to deviate a step from Holy Writ and dogma; it was rather designed to establish an understanding of what the Church taught or prescribed; hence the students of the Middle Ages used up their energies in discovering proofs (for what already existed) and in this way developed cleverness and rapidity of thought. But to think,—to understand, —to lead,—this teaching came from the books of the greatest teacher of ancient Greece, Aristotle, who passed into the Middle Ages as the most exalted authority of learning, whose teachings were followed blindly. The best known scholastic was St. Thomas Aquinas, the Italian scholar, who, in the opinion of con temporaries, accomplished fully that which was the purpose of scholasticism, —that by the road of understanding the Church leads (man) in its teaching of God, culture, mankind; here however, the so-called scholasticism ended and lost the character erf teaching; it entered into discussions which had nothing in common with learning, but exerting itself for example in such a fashion that it might provide answers to such foolish questions as:

Would Jesus Christ have been able to save the world, if he had been born not a man but an ass ? or

How many angels could find standing room on the point of a pin? etc.

When then the Academy of Krakow grew up, scholasticism in Western Europe was already on the decline. But the Krakow professors undertook anew scholastic investigation,—that is, they began anew to investigate church teaching and to establish it by the aid of reasoning. The scholastic lectures did not enrich culture to a great extent, but they were immeasurably profitable to the Polish intellectuality of the Fifteenth Century. Scholasticism taught the young Polish head to think, to reason, to reflect upon God, the world, mankind,—in a word, Scholasticism was with us in the Fifteenth Century a profitable mental gymnastic. Further than this, scholasticism, and in general Church Teaching of the Middle Ages impressed upon man's memory the belief in this undying truth: that the chief task of man and of all mankind is to live (lit. behave) according to the teaching of Christ, that, therefore, moral-religious culture is the sun about which must revolve culture of the intellect, culture of the arts, and culture of all things material. This ideal of the Middle Ages is reflected most beautifully in the celebrated work of the Fifteenth Century German, Thomas a Kempis, "De Imitatione Jesu Christi."

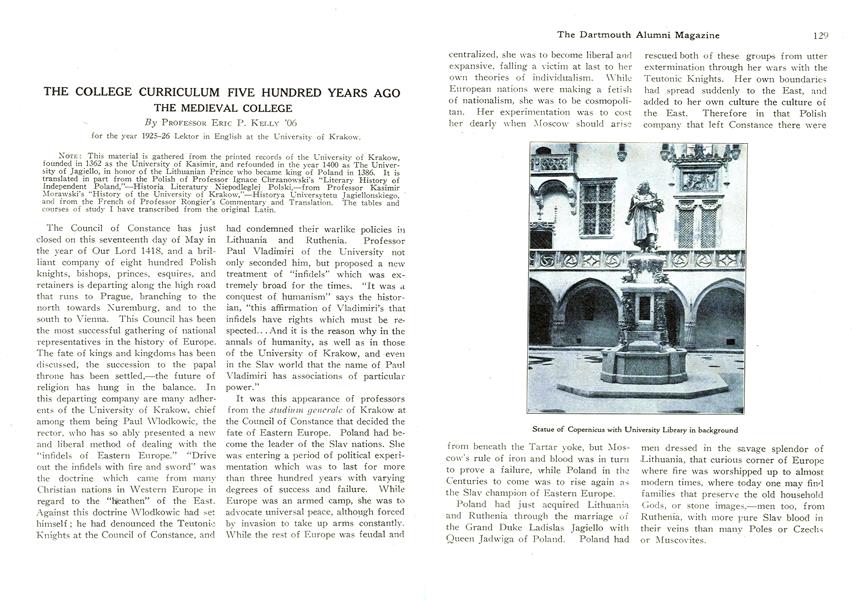

Statue of Copernicus with University Library in background

The old Jagiello Building, built in the fifteenth century

Going to Cambridge Courtesy of the Pictorial

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1926 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1926 -

Article

ArticlePHYSICAL FITNESS WORK AT DARTMOUTH 1925-26

December 1926 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Article

ArticleC. F. RICHARDSON'S TRIBUTE TO THE GREAT PRESIDENT

December 1926 -

Article

ArticleWHY THEY DON'T ATTEND MASS MEETINGS

December 1926 By Harry R. Wellman '07 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEETS IN BOSTON

December 1926

Professor Eric P. Kelly '06

Article

-

Article

ArticlePOLITICS AT DARTMOUTH

November 1920 -

Article

ArticleDormitories Named

June 1929 -

Article

ArticleCollege Sanctions Beer

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleYour Brother's Keeper

June 1942 By WILLIAM W. GRANT '03