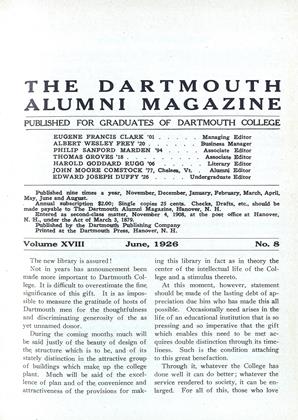

Not in years has announcement been made more important to Dartmouth College. It is difficult to overestimate the fine, significance of this gift. It is as impossible to measure the gratitude of hosts of Dartmouth men for the thoughtfulness and discriminating generosity of the as yet unnamed donor.

During the coming months much will be said justly of the beauty of design of the, structure which is to be, and of its stately distinction in the attractive group of buildings which make, up the college plant. Much will be said of the excellence of plan and of the convenience and attractiveness of the provisions for making this library in fact as in theory the center of the intellectual life of the College and a stimulus thereto.

At this moment, however, statement should be, made of the lasting debt of appreciation due him who has made this all possible. Occasionally need arises in the life of an educational institution that is so pressing and so imperative that the gift which enables this need to be met acquires double distinction through its timeliness. Such is the condition attaching to this great benefaction.

Through it, whatever the College has done well it can do better; whatever the service rendered to society, it can be enlarged. For all of this, those who love Dartmouth, and their name, is legion, will rise up and call the giver blessed.

Last year a systematic effort was made to discover what was the average expenditure of money by Dartmouth students in a year's time. On the basis of replies received in usable form from 648 of the nearly 2000 students, it was discovered that the average expenditure was $1535 a year—a sum somewhat in excess of what theory alone would have suggested. This merely amounts to saying that the guesses had been inaccurate. The proportion of replies seems reasonably sufficient to give a fair line on the whole, and taking into account the advanced costs of everything it is on the whole not surprising. One merely wonders whether, in the comfortable old days when the catalogue used to guess that the average worthy student could worry through on $500 or thereabouts, the average expenditure wasn't really a bit higher than that.

Certain interesting sidelights are reported. The lower quarter of the student body, speaking financially, is revealed as standing best in the scholastic record. The men who spend the mostthe upper quarter—have the poorest scholastic standing. That will surprise no one. It is what any one would guess, and it is probably true everywhere. Moreover the men who come to Dartmouth from a distance are commonly found in the quarter which spends the most money, which is also natural. Those who can afford to attend a college two or three thousand miles from home are usually in circumstances comfortable to a more liberal expenditure. Otherwise they would probably seek a college close by, or avail themselves of state universities.

On the face of it Dartmouth at present musters a much larger proportion of students whose worldly circumstances are easy than was true a generation ago. One can see that at a glance, even allowing for the inherent deceitfulness of appearances. It is reassuring to be told by those in the best position to know that this increment of what one loosely calls "rich" students appears to have had no deteriorating effect on the general democracy of the student body, and has certainly not given it the reputation of being a "rich man's college" which some others have acquired. The proportion of scholarship men and of men who work their way through is still creditably great.

What does not quite clearly appear from the study made of student expenditures is whether or not this increase above the conjectured average is due to the power of a comparatively small group to spend a great deal more than others and thus bring the average up. That is possible, and average figures are bound to be more or less unsatisfactory in any case because of this possibility. The impression one gets is bound to be that the lift is due to a widely distributed element, and that students in general are spending a great deal more than had been suspected, when in reality it may be that the conjecture was fairly close to the facts and that a special lavishness in some restricted group is what makes the average mount so unexpectedly above the supposed levels. On the whole, however, it seems fairly well established that this is not so, taking the character of the responses into consideration and that the average figure, $1535 a year, is not far out of the way in fact or in seeming. But it is a far cry to the time when a Dartmouth student could say, as one recently did, that his total cash outlay for the expenses of freshman year at Hanover was $212, including everything.

There are notorious disadvantages in being a "rich man's college," and we suspect there are fewer inherent virtues in being distinctively a "poor man's college" than is generally recognized. The better and healthier situation may well be that safe middle ground so praised by all philosophers including Greeks and Latins. A college that is neither the one thing nor the other exclusively, but rather an average cross-section of all degrees of society as it exists in the country today, seems infinitely to be preferred if it is to fit young men to go forth with genuinely tolerant and honestly liberal ideas, rather than so acutely class conscious that every view is warped. We would not have Dartmouth other than it is—which is to say, genuinely representative of present-day America. To have it overbalanced one way or the other, by riches or by poverty, would seem to us undesirable in the extreme. It is better as a sort of accurate microcosmbetter for the College as an institution, and better too for the men in it.

It may be well if all colleges stress for a season somewhat emphatically the fact that intellectuality is not convincingly attested by more readiness to take the unexpectedly radical attitude. There has grown up within the past deoade a company of enthusiasts who delight to refer to themselves as "intellectual's" without affording any very cogent evidence of a right to that honorable designation, and apparently placing the chief reliance upon the fact that members of the cult are in a state of perpetual revolt against the established order of society, industry and (so far as such a thing is recognized at all) religion.

It is an attitude of mind which naturally makes its strongest appeal to immaturity and such as lack experience. There is a glorious age at which one has lost none of one's illusions. At such a time one is most keenly appreciative of the shortcomings of one's elders and most confident that if youth be given the tiller for a few moments the human race can be got back on its appointed course. Hence the numerous "youth movements" in various countries—mainly in their eager emulators over here. The colleges have flowered forth with Round Tables and kindred organizations devoted to the favorite indoor sport of the "intellectual," which seems to be "challenging" everything hitherto accepted as truth. Youth is from Missouri—and then some. It not only demands to be shown, but usually also implies that your case is hopeless from the start, if you expect to succeed in proving that anything old has any merit.

The anxiety to pose as "intellectual" may be set down as an amiable passion of the sophomoric in most instances, we believe; but unfortunately so many of us remain sophomores for so long a time that the pinky tinge abides even into what should be the earlier years of discretion. What we are getting at, however, is that calling this class of rebellious human being "intellectual" does not necessarily prove anything as to its collective intellect. The name is, in fact, very seldom descriptive. Moreover if it were so, these apostles of revolt and the chief editors of most undergraduate periodicals would be graduating with magnacum laudes at the very least. For it has become the fashion among college editors to be tartly sarcastic in the condemnation of pretty nearly everything that is, while intimating a shining faith in about everything that is not. Eheu,fugaces labuntur anni! One remembers when one was very much like that—only in those days one took it out in spluttering conversations in the sanctity of one's dormitory and seldom or never lectured the world in super-confident print concerning its manifold sins and silliness.

The college press, which was formerly a rather colorless affair with a notion that its major and often rather diffident concern lay in the field immediately at hand, has become something very different. It does to some extent bestow an occasional and rather patronizing notice on its immediate environment, especially when (as frequently happens) there is some banality of the faculty, trustees or unduly conservative students to rebel against. But one must not suppose that any such pent-up Utica contracts the powers of the youthful tripod. The world has become the province of the editorial writers and is no longer monopolized for an hour or so on Commencement day by four hand-picked orators from the senior class. If the world does not speedily become a better place, it will not be for any lack of advice from the eager young.

Unfortunately the outside world seems to be almost as unresponsive to the cleareyed youth who write flaming editorials for the college press as it is to the Commencement speakers; and occasionally one has a spell of wondering just how much stock even the immediate auditors of all this eloquence—the students to whose attention it is primarily addressed take in it. Is it instructive authoritative, provocative—or just amusing? Is it accepted as a display of burning sincerity, or rejected as a theatrical pose adopted because for the moment everybody's doing it? In any case it is interesting but does it convince ? Does it represent undergraduate opinion, or does it derive its principal thrills from the fact that it doesn't do any such thing? One has moments of suspecting that a radical in a world of radicals would have a very thin time of it and that half the zest of being a bolshevik resides in the knowledge that most other people are going to be shocked. If there were no persecutions for the sin of unlicensed speech, what should we do for martyrs ? Othello's occupation would be gone. Even the college editors would have little to write about if every one else were as radical as one is told every one ought to be.

The announcement made a few weeks ago by Johns Hopkins University that it proposed to abandon its undergraduate department—which we believe covered only a two-year course—and revert to its original purpose of awarding only masters' and doctors' degrees seems to accord with a tendency occasionally remarked upon by President Hopkins as characteristic of the modern universities and as pointing toward the time when every university will do the like. That this is a result to be looked for in the immediate future may be doubted; but it is nevertheless the fact that the universities which include the undergraduate college tend more and more to subordinate that feature and to lay the greater stress of ..expenditure and development on their graduate schools. It will not be surprising if in the course of years more of the larger universities abandon the purely collegiate functions altogether and leave them to be performed by the institutions which profess only to be colleges, thus providing the ripened material for the universities to operate on.

One suspects that the greatest resistance to this plan would come from the alumni of the university who remembered its undergraduate activities with affection and who have never accepted the product of a mere graduate school as a brother in good and regular standing, for any purpose other than that of contribution to endowment funds. To be a Harvard man, in the estimation of Harvard men, very rightly means that one must be a graduate of the college, rather than hold a degree in law or medicine after having obtained an A.B. somewhere else. Such considerations would weigh less at Johns Hopkins than elsewhere and the abandonment of undergraduate education must naturally come there with the most ease.

In line with what has been said several times in these columns concerning the different problem presented in the case of American colleges from that presented in the case of British universities, let us quote briefly a discerning utterance by Mr. M. C. Hollis, a member of an Oxford debating team recently touring the United States, as embodied in an article in "The Outlook". He says, speaking of organization as the outstanding difference between an American and an English college, that to a British eye the organization of the student's day seems excessive. "Classes are compulsory," he notes with some surprise, and "every breath that the student takes is the university's business, and he must breathe it at an appropriate and scheduled time." He then proceeds as follows :

"Still, for this organization in the universities there is a more special reason. Here, as in so many other things, America has undertaken a task quite different from any that the world has ever before seen. The European or English university has been able to leave the student much freedom to learn, as he chooses simply because it has made no attempt to cater for the student who does not choose to learn at all. The European university has always been an asylum for the oddity with a kink for intellectual interests, a refuge for the minority. America, the first to do so, has tried to give a college education to everybody. The experiment has demanded the price.

"I have heard Americans argue that she has by so doing stultified the very purpose of higher education and sacrificed ability to mass mediocrity. Be that as it may—and there is much to be said on both sides—it is evident that it makes education's problem very different. For not only has it brought a volume of students to the university, for parallel to which we have to go back to Europe before the Reformation, but—and here the comparison with the mediaevals breaks down—the great majority of them cannot love learning for its own sake. For the taste is rare. The critic who remembers this finds many of his criticisms answered. Organization? Yes. But what sort of people are you organizing?

"But here is a question that will not down: Granted that organized athletics, the fraternity system, the amassing of credits, are wise policies with which to meet the problem of the indifferent numbers, are you not sacrificing to them the genuine lover of learning? And is not a system of education which does such a thing a very parody?"

Whether or not it is a parody, it is certainly true that our system does of necessity, thus far, "sacrifice to the indifferent numbers the genuine lover of learning;" but one should not therefore rush to the conclusion that the price, though great, is not worth the paying considering our national needs. We have for some years suspected that the curious condition of this country makes the production of a few ripe university scholars a less vital matter than the wholesale production of a mess of young people to whom little more than the outlines of cultivation have been made clear. This always irritates the devotee of learning for learning's own sake, and the colleges themselves are earnestly striving to in- crease as much as may be the number of those who thirst after culture. Never- theless the fact remains that, so long as our young people insist on going to college in perfect armies, there is a hard and fast limit set to our emulation of the British idea. Those fitted for ripe scholarship to be pursued mainly under their own responsibility, must always be few by contrast with the multitude annually matriculated and annually graduated in the United States. But does it matter?

Is it not, on the whole, well to add to what would otherwise be the sole work of a college the largely ineffective attempt to bestow higher learning on the more or less indifferent? Nothing appears to be lost, even if discouragingly little is gained. Our great mass of college graduates does not shine, intellectually, like the highly polished product of a European university; but we may by due diligence save some,—and the many, even if not sent forth as scholars, can hardly have been harmed. It is the inevitable sequel of our effort to throw open higher education to everybody, and the only possible contention seems to be that to do this is a mistake—that education is the rightful prerogative of the very few who can make the very greatest use of it. Thus far, Americans hesitate to take that viewand until they bring themselves to do so our colleges must probably continue with many of the attributes of lower schools in order to promote even a tolerable result. It is the essential defect of our environment—if it be really a defect. Our feeling is that it serves the requirement of our times, with all its failures to reproduce the standards of Oxford and Cambridge.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES HOLD ANNUAL MEETING IN HANOVER

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleSOMETHING ABOUT BUSINESS

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1926 -

Article

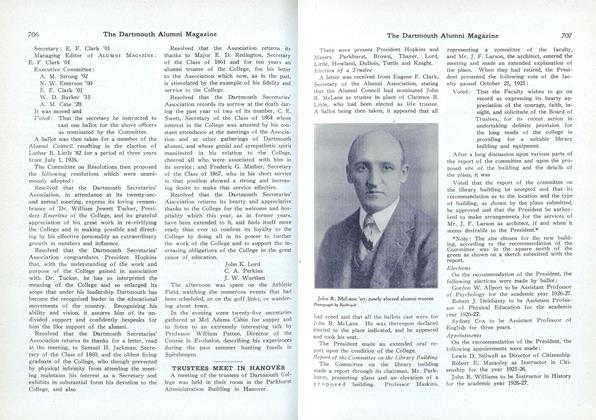

ArticleTRUSTEES MEET IN HANOVER

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1876 FIFTY YEARS AFTER

June 1926 By Samuel Merrill '76 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

June 1926 By H. Clifford Bean