Address to the members of the graduating classes of the Thayer and Tuck Schools, April 15, 1926, by Henry B. Thayer '79 of the Board of Trustees of Dartmouth College and Chairman of the Board, American Telephone and Telegraph Company.

Transactions involving the transfer of property fall into one of three classes: Charity, Business or Robbery.

Real charity, of course, is founded on altruism. In robbery the property is transferred unwillingly under the influence of a superior force and with no benefit to the party surrendering the property. The basis of business is fair exchange for the benefit of both parties. The seller sells because he thinks the price more valuable to him than the thing sold. The buyer buys because he thinks the thing bought more valuable to him than the price.

Now in business itself there is an infinite range—from bootlegging to banking and from the kinds of business in which you hope you will never meet the same customer twice, to the kinds in which good will is reckoned among the principal assets. The kinds of business which depend largely upon opportunity and are not governed by rules nor guided by experience may be eliminated from our consideration.

What I have to say applies to constructive business ; the kind which plans for the future and assumes continuance and permanence. Now as the basis of business is fair exchange—seeking a profit and permitting a profit, each party looking after his own interest, it follows that the safe guide in the conduct of business is enlightened self-interest, a broad and farseeing view going beyond the individual transaction and establishing policies and principles which, if faithfully carried through, will build up a business. Sound policies and principles can only come as a result of sound analysis and reasoning.

So my text is on the necessity of applying that kind of analysis and reasoning to the determination of what is really for your interest. Assume that you are the chief executive of a business concern and you propose in directing that business to be guided only by the interests of your concern. What does that involve? The prosperity of a particular business is usually more or less affected by prosperity or depression in general business. Among other things affecting general business prosperity are legislation and government. The American business man is rather prone to complain of government interference and bad legislation and blithely go off to play golf instead of voting on election day. If you do vote, vote intelligently. A friend of mine told me of a conversation with his son who had just cast his first vote. He asked, "How did you vote on the proposed constitutional amendment?" "Voted, yes." "What do you know about it?""Nothing."He then called his attention to the fact that the Constitution was the product of the best minds in the state after careful deliberation and that the whole structure of government was built upon it and that if he could not know and understand the merits of the question it would be wise to vote "No" or not at all. It is a part of the business man's job to take an intelligent interest in government and civic affairs. We have only to look at Mexico, with wonderful natural resources and their lack of development, to realize the importance of a stable government to business.

The prosperity of a business depends to some extent on certain things which affect particularly that class of business, and associations are formed like Graindealers' Associations or Fruit Growers' or Lumbermen's or Farmers' Associations ; sometimes dominated by the thinking men, but more often by secretaries, some making campaigns for what they think is for the interest of the trade and some making a show of activity to keep the job alive. A favorite activity has been pressing for lower freight rates. "Lower freight rates" is an attractive slogan to the unthinking. To the thinking man the slogan would more properly be, "The right freight rates."Farmers have seen wheat rotting on the ground for lack of transportation facilities. Manufacturers have been hampered and put to great expense by lack of transportation facilities to bring them raw material and carry away their product. To have those facilities the railroads must have profits sufficient and sufficiently safe to attract investing capital. Give your backing to movements to which you have given enough thought to be sure that they are what you really want.

Then there are boosters' clubs under different names. To the extent that they promote genuine co-operation for proper purposes among industries they are good. If the object is to induce an industry to locate at Bird Centre which economically should be in Podunk, it is bad. I can conceive of a set of conditions which might involve in international trade the subordination of commercial progress to national progress, but generally speaking, within the country it is probable that any diversion of trade from natural channels by artificial aid or restraint is in the end harmful.

As affecting the class of business in which you are interested there is another activity to be thought of and that is by precept and example, trying to keep your neighbors on straight lines and in good repute. When a concern's methods border on robbery, and robbery, by the way, is transfer under constraint by imposition of artificial conditions, as well as transfer at the muzzle of a gun, it is bound to react not Only upon that concern, but upon others in the same, kind of business. As you know, there is no more potent factor for economy than combination involving mass production, mass distribution and the elimination of competition. Competition in business is praised and taught and preached, but after all, it is a concession to human weakness. It is a clumsy and very costly stimulus to progress which should be actuated by intelligence. The latter part of the last century was an era of combinations, but some of these combinations, instead of letting their customers participate in the advantage of the economies, as would have been wise, so abused their power, that the result of the public revolt which followed went farther than curbing the abuse and practically made combination itself a crime to the extent that it eliminated competition.

The greatest danger to business prosperity is usually the unreasoning, unreasonable and shortsighted business man. It has been suggested that sometimes a vigilance, committee would be good for business.

Coming from general to the particular business, there is, I take it, no need to say that it pays to treat customers fairly in a business that aims to be continuous, but there is another very important relation where the principle is not so generally established and that is the relation between employer and employee. There is a word "welfare" which I do not like and which carries with it a vague implication that decent treatment of the employee is due only to a desire to minister to the welfare of the employee. If that is the case, it is charity and not business. The American wage earner should, not be an object of charity and certainly does not want to be.

Whatever is done in that line, I think should frankly be for the welfare of the business. It pays to do whatever in reason can be done to secure contented and loyal employees and first of all that involves fair wages, but it involves much more. It involves opportunity for advancement, good working conditions, something to appeal to the ambition and imagination and the joy of accomplishment.

If an employer relies on force of circumstances to hold his employees at unreasonably low wages, it is robbery and if employees rely on force of unions to get unreasonably high wages it is robbery. Trade unions ought not to be necessary, but I admit that I have heard an employer brag of having fooled his employess and I do not know of any remedy in such a case except the union. The union ought to represent the best interests of its members, but in some cases it surely does not. Certainly in some cases it represents the temporary interests of the union or of the officers of the union, even when opposed to the interests of the members individually. A union ought to make a distinction between a just and unjust employer. It does not. I have sometimes thought that it preferred the unjust. Remember that there is a distinct difference in interest between labor and the union. It is for the interest of the union that its members should be discontented. It thrives on grievances. The contented wage earner loses interest in the union and fails to pay his dues; so that where there is a union there are three parties with more or less diverse interest, the employer, the employee and the union.

A fair wage is a wage which gives to the laborer a standard of living and saving proportional to his contribution to industry and wealth. That is the standard to be desired. On the other hand, the employer must keep to a prevailing scale or go out of business. One of the things the War did for us was to raise the prevailing scale to a higher level than has ever been reached in any time or by any people,. The average man in the United States, therefore, has a higher standard of living, he earns more, spends more and saves more than any other average man anywhere. It is getting to be fairly well established that a higher wage and a higher efficiency go together, so that except in abnormal conditions, whether or not a higher scale will cut us off from some foreign trade until wages abroad come approximately to our level is at least debatable, it is probably true that a return to pre-war wages would kill a domestic buying power far greater in value than any foreign trade; we may lose. One of the most hopeful signs of the times is the greater intelligence with which labor questions are considered. In this connection some extracts from a report made last October by the President of The Federation of British Industries may be interesting. He says :

"The American employer believes in high wages, and he pays them. But he also believes in high output, and he sees that he gets it. In view of the shrinkage in the stream of immigration, and therefore more particularly of the pool of unskilled labour, it is becoming more and more important for labour saving devices to be used to the greatest possible extent. To this labour offers no opposition, and the result is a constantly increasing efficiency in production with a constant striving towards greater mechanical efficiency, and a comparative freedom from the restrictions on output which hamper us in England. There is no doubt that on the whole the spirit of labour in the United States is excellent. ... In the United States cooperation between capital and labour seems possible and the fatal doctrine that there is a necessary conflict of interests does not prevail. . . . There is a spirit abroad in the States which is sometimes referred to as the "new leadership," and it is a spirit of cooperation, of initiative, and of a "square deal" on both sides. This spirit alone goes far to explain the amazing increase in the efficiency of American production."

You may think that I have given too much time to trying to prove the obvious, but there is some tendency, especially in smaller concerns, to prefer sharp practice to fair dealing, to argue that it is good business, in every transaction, to take as much as the law allows.

That is not good business and I believe for all concerned it is better to have it established as a business principle that fair play pays, than to have fair play depend only upon the character or temperament or whim of the manager.

Principles endure, managers change. If you are thinking of business as a job that is one thing; if you are thinking of it as a career that is quite another thing.

It is my belief that, if viewed and carried on as a career, business as an intellectual occupation is second to none. It involves the keenest possible analysis of the general and specific problems of your business and of yourself and your capabilities and of the conditions to be met and of what you have to meet them with. And as the factors are continually changing, the analysis and the reasoning must be continuous.

lam a strong belie,ver in the desirability of having a pretty definite program of knowing what it is intended to accomplish and the way in which it is proposed to accomplish it. You may change the program as conditions change and as your views change and you probably will not keep exactly to program, but you are much more likely to arrive than if you simply drift, and going with that you must have information about your business which is up to date and accurate. A favorite illustration of mine is the sailing of a ship; You must know your port, where you are and your direction and speed.

As an illustration of the difficulty of keeping strictly to program. You may analyze a business and construct an ideal scheme of organization. When you get to the point of filling the various positions you find that men are not standard, they are not made to specifications and you must modify your scheme of organization according to the strength or weakness of the men you have or can get. The point is to know why you vary from program and keep it in mind and get back to it when you can.

You must think straight. That is easy to say, harder to define and hardest to do. What I mean is that in thinking out your line of action you must not be swerved from logical reasoning by your emotions, your desires or your affections. It means, for instance, measuring yourself and your capabilities and considering yourself just as impersonally and critically as you do any man in your organization.

It is easy to fool yourself. It is more difficult to fool the people you work for. It is still more difficult to fool the people you work with and it is almost impossible to fool the people who work under your direction.

I do not know of anything easier than persuading yourself that the thing you want to do is the best thing to do, nor anything harder than for a man to measure his own ability as he would that of another. Last November, in a eulogy of Mr. Hughes, Mr. Root said, "He always thought about the job and never about himself."

That was the verdict of a very wise man on a ve,ry efficient and successful man. It's worth remembering.

Of course it is perfectly obvious that if a man allows his reasoning to be warped by likes and dislikes or by any personal considerations, to that extent it isn't good reasoning and his usefulness in a business is decreased. To put it another way: If you depend upon friendships or fellow memberships in some social organization or upon entertainment to carry on your business, you are depending upon the other fellow's weakness and not upon your own strength. I don't say that friendships are of no business value. There are buyers of a cheap type and sellers of a cheap type and there is a distinct value, particularly to a young man, in having a personality or an acquaintance or a reputation which will get him an opportunity to present his case, but having that opportunity, if it is to a serious man of business, he must rely on the strength of his case and his ability to present it.

It is perfectly natural that in what is called big business, the ideals, the ethics and the, standards generally should be on a higher plane than in small business, as they generally are, although there are exceptions in both classes. A man of some importance in a community will be kept straight by care for his reputation, when perhaps his morals might weaken. He has more to lose than a more inconspicuous man and is more likety to be found out.

It is the same way in business. A small local tradesman gets away with practices which, if applied to the business of a national concern, would bring it quickly into trouble. I didn't intend to talk shop, but, as an illustration, think about the Bell Telephone System: we have something over $3,000,000,000 in the business, the money of some hundreds of thousands of investors. We have something over 12,000,000 customers. Can you think of anything which it would pay us to do that varied a hair from what we believed to be straight and fair ? And another thing, we have two or three hundred thousand employees. Could we encourage or permit them to be crooked with our customers or anyone else and expect them to be straight with us ? Probably the, question is in your mind, "How about the officers of the traction company in 'Babbitt'?" There undoubtedly has been some crookedness in some managements and there probably is now and there probably will be and it is equally true that there are quack doctors and shyster lawyers and there are even ministers of the gospel who are better qualified to be confidence men.

However, there is no doubt in my mind, but that the standards of ethics are much higher in big business than in small business and are considerably higher than before the war, notwithstanding the generally demoralizing effect of the, war.

Unless a man keeps a true sense of values, he may be demoralized by business. Of course, the reason why a business is created is to make, a return on capital ; that is, to make money. A man in business sometimes gets the impression that the reason why he was created is to make money. Making money for him is a means to an end and not the end. And I also want to suggest in this connection that the sole purpose of education isn't to enable one, to make money. There has been, I think, too much of a tendency on the part of us Americans to consider education from the strictly utilitarian standpoint. I used to be frequently asked whether I thought a college education had any practical value to a business man. That question is not asked so often now. It is pretty well understood that it has.

I am sometimes asked now whether some particular line of study, the classics, for instance, has any value. Of course, any education which increases the reasoning capacity or the thirst for general information has value in business, or any other profession or occupation, but I would almost go so far as to argue that that Value is a by-product, and that the real purpose of the liberal college should be to give its graduates in any pursuits ideals and a greater capacity for intellectual enjoyment.

We are too likely to feel that the only relaxation from intellectual work is physical enjoyment.

I would like to try and impress upon you the tremendous increase in the responsibilities of the American business man over what they were fifty years ago when I was in your position—getting ready to go into business. At that time, transportation and such other utilities as there were, were largely in the hands of corporations as they are now Manufacturing was more generally in the hands of private firms and individuals. As late as 1890 about 3/5 in value of products was produced by privately owned concerns, while 20 years after, less than 1/15 was so produced. Both wholesale and retail distribution were almost entirely in the hands of private interests. That is in process of change through the natural tendencies of the larger wholesale business and through the establishment of chain stores in the retail business. The tendency toward corporate ownership is bound to gain force. The corporation is the agency which permits division of ownership. In private ownership the management is either identical with the ownership or is responsible only to a limited number of owners, presumably of some business experience. In corporation ownership the management is responsible perhaps to hundreds or thousands or even hundreds of thousands of owners, many of them investors of, their entire savings and many of them of no business experience.

Of course the moral responsibility is, under such conditions, tremendously increased not only for the safety of and return on these small investments, but indirectly for the attitude of the public toward business. If wage earners continue to become capitalists and part-owners in good business, the attitude toward business will be friendly. If they are encouraged to invest where they make losses, they will be embittered.

To my mind, with the business men of the present land future lies the answer whether we shall have increasing co-operation between the employer and the employee, until it is recognized by both that in the prosperity of industry lies the prosperity of both, or whether there shall be two opposing forces, and on that issue depends much more than the prosperity of this country.

It isn't so long measured in history since, in the so-called civilized countries, government in the interest of the governor generally prevailed. The fruits of industry were more likely to go to the aggrandizement of the rulers than to increasing the comlforts and luxury of the workers. The change has been gradual to government in the interests of the governed. That change had its greatest impetus in the adoption of our form of government. The industrial development here and the gradual betterment of a more evenly distributed high standard of living here accentuated it. Within your time you have seen, in the downfall of European monarchies, the outward and visible sign of the turn of the tide, but do you realize that with the war and the after effects of war, a new Age is definitely established and that this country is its leader and exponent? The problems of industry are being worked out here and in their solution we are far in advance of the rest of the world. Europe looks to us—sometimes unconsciously—as its model in industry.

From this time on, if we are sane and sound, and sanity and soundless imply fair dealing and broad vision, the influence of the American business man will be the dominant influence in the world. Under the old regime, the trader was despised—largely because he was tricky and took advantage of ignorance whether he was buying or selling. Under the new regime business should be the most honored of all professions and the patron of all other professions and of the arts and science.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES HOLD ANNUAL MEETING IN HANOVER

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleThe new library is assured !

June 1926 -

Article

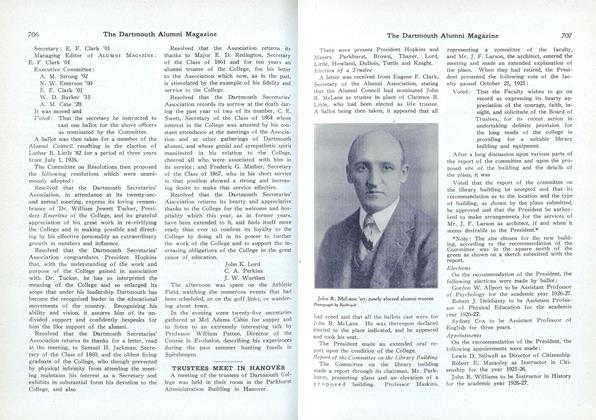

ArticleTRUSTEES MEET IN HANOVER

June 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1876 FIFTY YEARS AFTER

June 1926 By Samuel Merrill '76 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

June 1926 By H. Clifford Bean