Nothing could have brought to the attention of the Dartmouth community more forcibly the irresistible attraction of the world—the everyday world of action—for the student body than the flood. When roads became impassable, interest in mathematics was lost for the more pressing question of the possibility of the team's getting through to Providence. As soon as the extent of the damage was partially understood, classes were cut and study neglected for investigations of conditions at White River Junction, Wilder, and West Hartford. Three students left town in the hope of bringing out the news from Montpelier and Barre, where over 200 people were reported drowned. Others were deputized to help guard the streets of White River Junction. Still others worked all night to remove furniture from homes thought to be in danger of being swept away. No one outside the hospital failed to take a look at the flood.

Although all roads were reported blocked, J. Osmun Skinner '2B, managing editor of TheDartmouth and correspondent for the Associated Press, hired a car and set out for Barre and Montpelier at 8 o'clock Friday night to investigate the rumors of large loss of life in those cities. After a perilous 13-hour trip he won the honor of being the first person to penetrate the Barre-Montpelier flood district. In getting to Barre, normally 54 miles from Hanover by automobile, he travelled 109 miles and spent from 3 to 7 a. m. getting up one steep, slippery hill.

To get from Barre to Montpelier he had to walk the entire seven miles as several bridges were out. He arrived in the Vermont state capital just as the people were coming out of their places of refuge to view the havoc wrought by the 30-foot rise of the little Winooski River. Instead of the 200 reported dead, there was only one. After touring the city he walked back to Barre, looked over the damage done by the flood there and raced by automobile 50 miles to the nearest telephone and gave the Associated Press the first detailed account of the damage and loss of life in and around Barre and Montpelier.

The next day, Sunday, five Dartmouth students made the same trip by daylight. They were R. G. Rendell '28, M. E. Adams '29, E. P. Felch '29, F. A. Headley '29, and H. G. Hoch '29. W. O. Keyes '29 and R. I. Booth '3O were marooned in Randolph, Vt., while returning from a hunting trip in the Adirondacks and were forced to walk 35 miles to reach Hanover, the trip taking them two days.

Nine hundred Dartmouth men responded a few days later, November 10, to the call for volunteers to help Hartford (which includes White River Juncion) and West Hartford dig themselves out of the mud. Working side-byside in the mud with the students were Professors Stilwell, May and West. Seniors and freshmen, athletes and Phi Betes brushed shoulders and pushed wheelbarrows, all alike for a single day and for a single purpose. Dartmouth men made the mud fly doing work for which men could not be hired. Not only did they work from early until late, they communicated their enthusiasm and optimism to the flood stricken people. Tired backs and weary muscles were repaid by the gratefulness of the residents, who will long remember the aid rendered them by the Dartmouth "boys."

Six days later a group of 135 Dartmouth undergraduates made a second visit to West Hartford, which was the hardest hit of any place in this locality. They labored unceasingly from 8 a. m. to 6 p. m. filling in the streets and cleaning mud out of cellars in order that the houses may be occupied this winter without any danger of a typhoid fever epidemic.

Such active responses to calls for service demonstrate that there need be no fear of Dartmouth students losing contact with the world. There can be no accusation of Hamlet-like hesitation of ,Dartmouth men when aid is needed, crises are to be met or chances for action offered.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

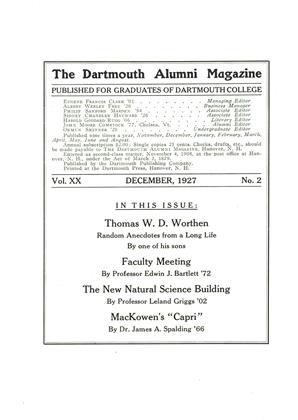

December 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHOMAS W. D. WORTHEN

December 1927 By One of His Sons -

Article

ArticleFACULTY MEETING

December 1927 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

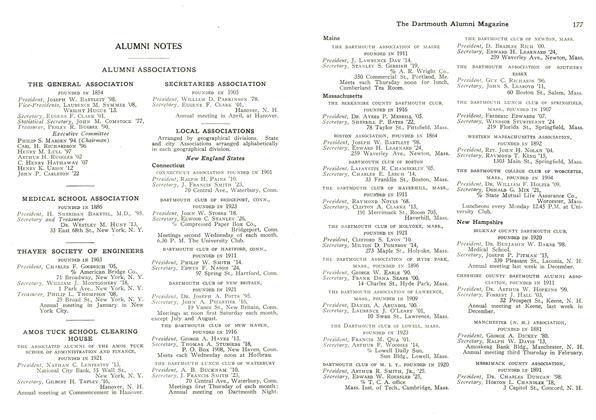

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1927 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1927 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh