New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry Emeritus

Lost opportunities can never be restored by regret. I admit with sorrow that during my undergraduate days I had no experience which qualifies me to give testimony concerning that formidable conclave the assembled faculty. My regret is made less keen by knowledge that not more than half who merited invitations to be among those present received them. A faculty summons was, if you believed the recipient, a decoration, and details of the reception were eagerly sought, analyzed, and discussed with much humor. We knew who thundered but never struck, who tried to be smart and trip the fellows, who became a sort of devil's advocate for the sake of popularity and who kept his mouth shut and looked sad. Any glint of facetiousness on so critical an occasion was noticed and reported with profound dissatisfaction; it was as much out of place as a joke at a funeral. The college man of today who is little disturbed by a summons to the police court for speeding if he has the price can have no idea of the dignity and mystery of the faculty tribunal sixty years ago and I suppose all the way back to the beginning.

Definite knowledge independent of hearsay came to me years later; but the methods were the same and I doubt whether they had been much modified since the Founding except to become a little less autocratic. This long period terminated about thirty-five years ago; and now with a faculty of two hundred and a student body of two thousand little remains of early methods of discipline.

In 1879, the date from which I can begin to speak from experience, precedent— "what we have usually done in such a case"—still controlled, if precedent could be known without too much conflict of memories. When established by reference to the clerk's record if necessary it was something of a tyrant difficult to escape from or change. Precedent lacks motive power. It is an argument from petrifaction. It is the means of withstanding the logic of a new set of circumstances. "We've usually sot" is no reason for sitting at the fourth wedding ceremony.

In recent years instances when students have shown interest in faculty meetings have been rare. That was not the condition sixty years ago. Meetings were then held in President Smith's study on the ground floor of his house (now No. 13 West Wheelock St.) and in the lack of better games it was considered good sport to listen under the windows for fragments of speech. Thus, and possibly otherwise, surprisingly accurate information frequently seeped about college before chapel in the morning. After Dr. Smith's time the president had an office in the second story of the bank building now displaced by Robinson Hall, and while there were rumors of eaves-dropping they were discredited because of the perilous way of escape. As one shrewd member of the faculty had a way of suddenly opening the door into the hall a guilty listener would have been compelled to take a long flight of stairs in two jumps to evade recognition. During a time of excitement, however, one professor placed under his door-mat each evening a brief report of proceedings for the benefit of a prominent senior who was correspondent for a Boston paper. The parties to this business are dead and if I should name a name all readers would take the view of some one—Hume perhaps—concerning a miracle, that it was too improbable to be established by human testimony.

When Wilson Hall was built the president's office was transferred to the room on the second floor over the front door, and for a time this was the official meeting place, later as the faculty came to use up too much air the assembly moved out into the reference room. But the faculty grew, and students found this perversion of the use of the room a reason for not using it themselves; so another move was made to the library in Tuck Hall until the stately apartment in the Parkhurst building offered a permanent home. And this has been once enlarged already.

Monday evening at seven o'clock was the well known time, and there was a lack of good form in allowing any other engagement to supervene. In fact it was not expected that there would be any other event on that night unless perhaps the ladies of the faculty wished to get together in groups, talk over their fancy work or do fancy work as they talked. Naturally affairs of the College or of the village were discussed and the profitable evening ended with the advent of husbands and with what were jocosely termed "refreshings."

The regular meetings of the faculty were always opened with prayer, all the faculty kneeling. The order of prayer, only one each night, was from senior to junior, and the record was kept and read in the minutes of the clerk. No one was omitted, but there were some who more often than others were late or absent on the evenings of their turn. On such occasions the president being more hardened to such duties generally took over the evaded office. Special meetings were not thus introduced, and this might be taken as a comment upon the value of the custom. For special meetings were usually occasioned by some kind of administrative emergency. This custom belonged to an age probably more serious and at any rate much more dominated by the forms of religion. Public prayer must be more or less of an art and is subject to critical listening unless in times of deep emotion. And in these days questions of its efficiency are raised and ancient customs are compelled to justify themselves. Prayer at the street corners, so to speak, may be too glib, too stammering, too long, too frank, too fervent and is not always for edification. It is a tough proposition for a novice and harmful if insincere. And how can an exacted prayer to order always be sincere! It sometimes happened that one honest petitioner lost all track of time, and a prayer which should have been to the edification of the younger brethren was merely irksome to their knees. Undoubtedly men engaged in the business of a college faculty need all the help they can get; the pertinent question is were they aided by audible compulsory petitions on the regular program. I can not assert that much inspiration came from that venerable custom. As the 19th century waned the president took this duty or aid or joy upon himself, and later it was given up. At present the younger faculty members would have ample time for preparation as at the rate of one prayer per monthly meeting it would be nearly twenty years before the turn of the latest addition to the permanent faculty, and many things may happen in twenty years. Certainly oratorical prayer as a circulating function would be as out of place as a Punch and Judy show at a quaker meeting. But let no reader consider these remarks frivolous or applicable to prayer in general. They only relate to the occasions stated—faculty meetings, or to be more general, To the Propriety of Audible Amateur Prayer on Formal Secular Occasions. They have no bearing on its place in religious services or on those great occasions when it seems natural to invoke divine blessing through those who are practiced in public speech. Ido not think it ever seemed unfitting, though unusual, that Professor H. E. Parker opened with prayer his regular classroom work at the beginning of each term. It was in accord with our idea of his character.

When the faculty were gathered together unless there was a special order action proceeded by call of the president upon each member in turn, seniors first, to produce any business which he had upon his mind. From the point of view of the more frivolous who were not yet used to their wives and were hoping that the meeting would be brief so that they could somewhere join the cosily chatting consorts for a game of domestic whist this was an obnoxious custom. It wasted good time to get around fourteen or fifteen in this manner even if they had nothing to say except to say that they had nothing to say. But worse, it stimulated talk for who wished to seem emptyminded about the interests of the College if he could think of something to bring forward. Senator Patterson had once spoken in public about the "dumb scholar" with severity, and no one wished to be a dumb scholar if he could think of any thing to talk about. I once knew a member of the faculty—a man of parts too—who said that he made it a point to speak as often as possible in faculty meeting for the sake of the publicity. Even when all went well to the last man such a one or one merely incontinent of speech was likely, "as long as there is plenty of time left," to introduce a topic which ran to an hour and a half of dilute talk and blighted all hope.

This little group transacted all the administrative business of the College which could not be loaded upon some individual of their number. The man who spoke first and moved that A, B or C be a committee to perform some un-scholarly duty escaped himself; consequently there was some rivalry in making nominations. There was no dean, no registrar, no superintendent of buildings, no secretaries for any one. The clerk and the inspector of buildings were the two unfortunate officers elected from the faculty to whom as many odd jobs as possible were delegated. Did they not get $lOO a year of extra pay ? The president might hire a secretary if he thought that he could afford it. It was not advantageous to belong to the Association of Animal Psychologists or the Union of Assistant Clock-Winders for if one was a delegate to some remote place like St. Johnsbury or Concord he took his expense money out of the children's shoes or something or stayed at home. The whole business reminds one now of the colonial chu'rch which allowed its minister $25 a year and half the fish he caught. These and other conditions seem like hardship but they were not. Those were small but happy days, and we expected nothing better in college life. Simple pleasures with congenial people compensated for lack of facilities for leaving home.

Through this tribunal scholarly insufficiency was eliminated and misconduct tried and condemned. In theory inadequate scholars were "dropped" on their records : but standards were a trifle vague and at times debatable. Either from malice or incaution the question "how Waster or Littlewit is doing" was likely to be thrust into any vacancy in faculty procedure. And as sooner or later all the faculty knew all the students such a question was the occasion for lively discussion. Often the faculty was divided into two unequal parties, the give-himanother-chance party and the he-has-had-chances-enough party. Few cases were so gloomy that one or another of the following arguments could not be used,— "His preparation for college was very inadequate." "He is working his way through college and it takes a great deal of his time." "He is- showing great interest in the work of my department and I should hate to lose him." "He is a good Christian boy and his example is very fine." And if he could bat .300 the younger members of the faculty kept very quiet. When the prosecution, with the good of the institution deeply at heart put the case, "He is a demoralizing influence and we have tolerated him long enough," little could be said further, as no one wished to be pointed at as tolerating a demoralizing influence. I think it can be said with truth that sympathy went out so strongly to the "low hangers" that many, proportionally, were retained and raised to tolerable grades who today with more accurately defined standards and greater competition for their places would be scattered abroad. It is a vague recollection that Washington Irving wrote that the early burghers in Manhattan represented to the Indians in trading for furs that each Dutchman's hand weighed a pound and his foot two pounds. In these faculty meetings sometimes stern Justice got a foot in the scales and at other times the Milk of Human Kindness was diluted too much, but the resultant of the foot and the milk was economy of indiscreet youth without wreck of the institution.

If this were the frank confessions of a young professor much could be said of early impressions when culprits appeared before this formidable court. A novice being trained as a familiar of the inquisition probably found his first experiences distasteful and yet felt a conscious curiosity how the victims would react to torsion of the thumb or a mouthful of melted lead. The criminals—respondents shall I say—were summoned to judgment by the tutor in person, or if there were two tutors by the junior. Although the duty was not delectable those cited bore this officer no more ill will than was implied in the title "messenger of the gods." The misdemeanors were chiefly cribbing in examination, hazing with violence, inebriation with undesirable publicity, and some other sins regarded of too delicate a nature for detail in a general meeting and therefore entrusted to a committee of more hard-boiled faculty members. The respondents, to make the best impression, appeared wearing collars and sometimes with specially shined shoes. They were notified that they were not expected to implicate any one else but that they must answer truthfully for themselves. This procedure was exactly the opposite of the criminal courts and under the circumstances far better. Acknowledgment was generally prompt and lying was unusual. The self-possession, good manners and gallantry of the young fellows in circumstances of considerable tension were admirable.

This tribunal dealing with all kinds of misdemeanors both academic and civil had occasion of irresistible though reprehensible amusement and also many reasons to question the wisdom of its own judgments. Some cases given penalties could more sensibly have been referred to a physician. With due regard for freedom of utterance balanced by responsibility, what, for instance was the wisest way of dealing with journalistic utterances of so personal a nature that they would promptly bring on a libel suit outside the academic walls? Long years ago a lad in his teens summoned for intoxication with noise, or in the language of the police court, for being drunk and disorderly, sadly confessed that he was a hopeless slave to drink. As he earned his own way to an honorable career and was an aid to others, a wise faculty might make inquiry similar to Lincoln's about Grant,—what brand of liquor was his master. Doubtless the members of the class of XtyY recall with as much amusement as I do their escapade of not less than forty years ago and tell it with joy. Good fellows but naughty boys, they had been sadly disorderly in a nocturnal racket which the faculty could not possibly ignore. Knowing what was coming they agreed, the just and the unjust, even those who were out of town at the time, to give no account of themselves when summoned by the faculty. After one or two had courteously but firmly declined to answer any questions, the faculty took time out for deliberation, and then in accordance with their decision suspended each recusant. After the faculty's policy was declared the messenger of the gods was not needed. It was only necessary to open the door of the faculty room to find members of the class waiting for their medicine in alphabetical order. In a short time the bubbles floated off, home was heard from, other colleges unreasonably demanded certificates of honorable dismissal. Pledges were declared off and in the same orderly manner they gathered to answer questions. If I remember correctly, there was so much joy over the returning prodigals that the original offense was passed over lightly. I have always had misgivings about the affair, to which I was a party; but under the conditions of the time only slowly changing I do not yet see how the faculty could have avoided floundering into a dead lock. To the modern Dartmouth student, if he reads this, the whole train of circumstances would seem amazing. But in its time it was no more surprising than that none of the class came to college in an automobile. The turbulence of the collegians of the first half of the 19th century was slow in passing away, and the faculties had more belligerent qualities. During the university period students of the college actually took maurauding professors of the university into custody and marched them to their homes. President Lord and his faculty did police work with occasional personal contacts. I saw President Smith work his way to the center of a rush and carry of the cane of contest. President Bartlett found it his painful duty to summon an unwilling posse comitatus and spoil several promising 'keg parties'. President Tucker, during whose administration civilizing was rapid, found it necessary at least once to send a representative of college authority to avert a student riot in a neighboring village. The great change, notwithstanding occasional relapses, is due to trusting to student responsibility, to more refined conditions, wider interests and very largely to the development of athletics as an outlet for superabundant energy.

But to return to alleviations of faculty routine. One warm evening a June bug was trying to "buz and butt its head against the window pane." Misled by spectacles the bug approached one of our most scholarly professors, when to the amazement of every one there was a flash and the whiz of a light cane and fragments of a disintegrated bug were spread around. Five or six husky lads of excellent general character captured and held in comfortable durance at a country inn a freshman obnoxious to their sophomoric dignity until after his class supper. He was to respond to a numerical toast which was expected to be disrespectful to his academic superiors. They sent a telegram to his anxious classmates, "Simpkins was going to toast XtyZ; XtyZ has toasted Simpkins." Of necessity they were hauled over the coals. They never knew the sympathy of some of their judges. "But didn't he make any resistance?" was inquiry made of a brawny boy who could have managed the affair without help. The apologetic somewhat sheepish reply, "I guess he thought it wasn't any use" caused some of the more volatile members of the faculty to struggle with a gigglte. A youth convicted of immorality in the stern and accurate language of the eighteenth century produced as a wholly adequate defense a duly signed receipt of payment "for services rendered." Samples these of the amazing variety.

There were three inevitable days of judgment each year, for at the end of each of the three terms was performed the solemn function of "reading the catalog." The clerk read slowly and distinctly the name of every student in college. It was a grand test of continence of speech, for with every name it invited comment, inquiry, praise or blame, discussion and motion. It was tedious but thorough.

The omelet is without doubt more noble than the sum of its constituents, but one may be pardoned for a rueful glance at the shattered shells. The intimate, considerate, inconsistent old faculty meeting has given place to better business. It has become a museum piece with the horse-car, the panorama, the hand brake and the red-hot stove on the passenger coach, the old oaken bucket, the muzzle loader, cotton stockings on invisible legs, and a host of other objects which were up to date in their time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHOMAS W. D. WORTHEN

December 1927 By One of His Sons -

Article

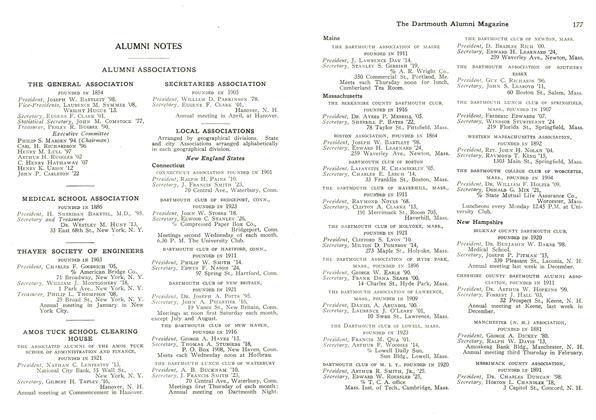

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1927 -

Class Notes

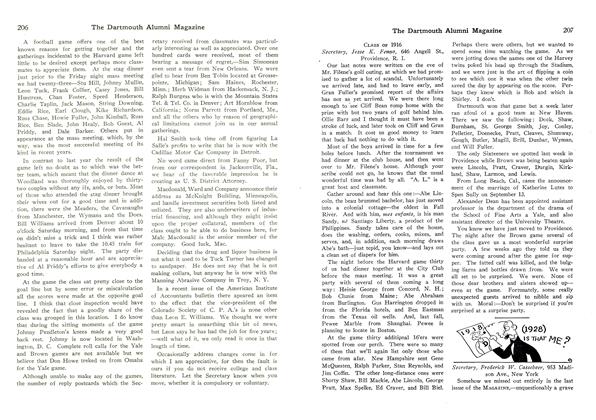

Class Notes1918

December 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1927 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

December 1927 By Herrick Brown

Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

Article"WHAT EVERY PROFESSOR OF SIXTY SHOULD KNOW"

January, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE OLD SONGS

April, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleSCRAPS OF PAPER

December, 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Sports

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

NOVEMBER, 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72