AN OUTING CLUB CUSTOM FOR FIFTEEN YEARS

The Winter Trip in the White Mountains has been an annual Outing Club expedition since 1911, with a single exception in 1919 when the Club went into the Franconias for lack of accommodations at the Glen House. During the fifteen years of its climbing the Presidentials in midwinter the Outing Club has steadily increased the scope of the Trip. In point of numbers, extent of territory covered, effectiveness of technique, and quality of interest there have been marked and continual gains. And in this period there has been but one major accident.

The course of this development which is faithfully recorded in the scrap books of the Club becomes particularly interesting this year when the activities of the Club are not only attaining a new peak of energy in number of trips and extent of country reached but are breaking new and promising ground in scientific interest in mountaineering. Without giving undue stress to a single small'trip, one may note with distinct satisfaction the record of a four-man trip which returned on December 24th from the first Dartmouth occupation expedition to Mt. Washington. This expedition spent three days at Camden Cottage on the summit equipped with instruments for the study of weather conditions on Mt. Washington in Winter. This is by no means the first winter occupation of the Summit, nor are its findings significant, but the fact of its occurrence is one of the hopeful signs that, the Outing Club is getting toward the use of its' facilities for work of essential value.

For the Dartmouth Outing Club is a means not an end. We have sometimes forgotten that, in our eighteen years of strenuous emphasis on establishing, organizing, and standardizing technique for enjoying outdoor life at Dartmouth. The significant activity of the Club begins beyond its mechanics of operation. It begins where undergraduates find in the contact with Nature, streams, slopes, summits and all that makes the experience they provide; and in the revelations of human nature in their companions and the people of the region, a stimulation to creative thinking. When Dartmouth undergraduates come to represent these unique and varied experiences in verse, prose, sketch, and perhaps song, when they actually carry their science into these first hand experiences to aid in interpreting them, when they consciously observe the varied phenomena of human experience and balance the results against their narrow and specialized backgrounds, then we shall be making the use of this distinctive opportunity in Dartmouth life which alone can justify the interest of intelligent men.

The two trips taken up Mt. Washington at Thanksgiving, this Christmas trip, and the three trips which will go at Washington by three trails in February demonstrate the most general interest in winter mountaineering that the Club has ever seen.

Back in 1911 the mountains presented a quite different spectacle to the first Outing Club climbers. Without equipment or experience they were appalled by the vast snow cap with its sudden changes of bitter weather. Of seven members of that pioneer trip only one reached the Summit, and he went up with a visitor at the Ravine House to rescue the others who were thought to be in difficulty on the Carriage Road. C. T. Jones 'll was apparently the first Outing Club man to ascend Mt. Washington on an annual mid-winter trip.

"The Mountaineer" in the Boston Evening Transcript told the story: ".Leaving Hanover on March 3, they spent Friday night at the Ravine House in Randolph and started on Saturday for the Glen. The party had no creepers and it was decided before leaving Hanover that the climb would be only as far as snowshoes should be available. The start at the Glen House was at 9.45 a.m. and the shoeing on the Carriage Road was excellent- and till the Halfway House was reached the party kept well together. On the exposed slope between it and the Graveyard the wind had blown the snow away and the icy surface made snow shoeing out of the question. Taking off the shoes, the party kept on, the president of the Outing Club, F. H. Harris using skiis instead of alpenstocks. . . . Under the shelter of Nelson's Crag the shoeing was good but as it was 1.40 p.m. and the party had had nothing to eat since 6 a.m. and as the provisions were with the rest of the party, it was deemed best to return to meet them. Just above the Graveyard the main party had halted and decided to return to the Halfway House for lunch. With that party was Mr. Chase a visitor at the Ravine House, who had come with ice axe and creepers, and fearing that the boys [advanced party] might get into trouble volunteered to go up and find them. C. T. Jones of the Dartmouth Club went with him and the two started directly up the slope thus cutting off' the turn in the road. It so happened that Harris and Watts (the advanced party) had already passed down over the road, but the rescue party did not see them. Chase and Jones pressed on to the rescue and presently found themselves at the Summit where they registered at the express office. The day was a beautiful one, with a cold wind at the Summit but a warm sun. It was exceptionally clear. On the return Harris, with skiis, made the distance from the Halfway House to the road at the Glen in fourteen minutes. ..."

The following day was spent working Mt. Crescent, Monday saw the party back in Hanover.

The danger and difficulty of the ascent of Washington left such an impression in the minds of the climbers that the following year the Dartmouth published, a day or two before the trip of March 9- 12, the following statement:

"The Club will not attempt the ascent of Mt. Washington and all men will be distinctly discouraged doing so, since the ascent of the height is impracticable to any but trained alpinists with axe and creepers; the danger of being lost in a sudden snow storm is ever present at this time of year."

However, fifteen men made that second trip, took up quarters at Glen House, and explored the floor of Tuckerman's via the Carriage Road and Raymond Path. After being driven back by a blizzard the first day on the Carriage Road, the party divided and three men reached the Summit by the Carriage Road on the second day. They were C. E. Shumway '13, G. L. Watts '13, and J. L. Dallinger 'l4.

In 1913 the third trip took twenty-four climbers of whom seventeen reached the Summit. Three men made the ascent to the Summit on skiis and claimed the honor of making the first ascent of Washington on skiis. Shumway, President of the Club, was accompanied by F. H. Harris '11, and J. Y. Cheney '13 in performing this feat. His account of the experience was published in the Boston Evening Record for March 15.

"All (three) reached the Summit after exhausting struggles, the first time, so far as can be learned that any person ever climbed Mt. Washington on skiis.

"The experience was indeed hazardous. The wagon road was banked in with snow in a deep 'slant down the mountain and in a number of places its icy crust would cause our skiis to start sliding down the mountain sideways. . .

"But perhaps the most thrilling part of the adventure was on the return trip. Harris, Cheney, and I roped ourselves together, about 100 feet apart, and coasted on skiis down the wagon road. In that way when one would lose his footing and begin sliding down the mountain the others would snub him back. That four-mile coast to the Halfway House was a wild heart-beating, thrilling ride that fully repaid the extreme exertion of the ascent.

"At times our speed would be accelerated to such a degree that we would shoot off the road on the curves and we were able to stop our career only by the quick use of picks or being "snubbed" back."

The 1914 trip of March 7-8-9 placed seven men at the Summit and ascended Tuckerman's as far as the site of the snow arch. They were able to lower the running time from Halfway to the Glen to 13 3-4 minutes. A year later, however, twenty-nine men made up a trip that took twenty-three to the summit, scaled the Headwall of Tuckerman's (one man also descended the Headwall), and climbed Madison.

Two trips visited Mt. Washington in the winter of 'l6. The official expedition numbered thirty-six and reached the Summit with thirty-four. E. L. Mack '16 set a record of 12 3-4 minutes for the Halfway House-Glen Road ski run which has not since been equalled. George C. Arnold with three companions on a small trip climbed the mountain on skiis that winter and recorded a watch time of two minutes from the six-mile post to the five on the descent.

The next year placed five men on top by way of Tuckerman's Headwall. The trip was extended to four days and was accompanied by a motion picture photographer. Although the record of the 1918 trip is missing, it was announced in the Dartmouth as a five-day trip starting February 21. The next year found the Club in the Franconias with forty-two men quartered at the Profile House. The Glen House was not available that year.

1920 was marked in Outing Club mountaineering by the institution of a Fall trip of twenty men and a Winter expedition of fifty-five climbers and pinochle fans who occupied the Ravine House. Madison and Adams were conquered and Sherman Adams '20 led a descent of King's Ravine.

When E. G. Plowman '21 led a doubleheader trip operating from Pinkham Notch huts on March 5-8 and 8-11, 1921, with twenty-two men in the first section and nine in the second the plan which has since been often followed was developed. The comparative interest of present Club members may be seen however from the fact that this year's Thanksgiving trip, run in two sections led successively up the railroad from Base Station by E. M. Raymond '28, was as inclusive as the 1921 mid-winter trip.

Between '21 and the Christmas trip of this year, the principal innovation was the shooting of the Headwall of Tuckerman's Ravine. This feat which is said to have been borrowed from hutmasters of the Appalachian Mountain Club consists in sliding the crust of the Headwall from the last exposed rocks perhaps five hundred feet above the floor. This latest of the spectacular stunts which have marked the evolution of the mid-winter trip is the high point of the adventure at present.

There is no such thing as a typical trip in the White Mountains in Winter. The Scrap Books are filled with accounts of fierce struggles in deep snow, low temperatures, and gales, to say nothing of the physical difficulties encountered in topography. Men have been blown off the Carriage Road, have taken dizzy slips down the treacherous snow slopes, have frozen faces and fingers. Trips now carry complete equipment for the worst possible conditions; yet, occasionally, clear mild weather and grassy slopes make the climb an ascent from valley Winter into summit Spring.

Such a trip was the 1925 jaunt. Twenty-seven of us left Hanover on the afternoon train north on February 21. Our equipment (now standardized and required) included Poirier packs, parkas, skiis, poles, snowshoes, ice creepers, double mittens, three heavy wool shirts, double knitted helmets, wool underwear, heavy socks, knife, matches, and rawhide. In the general kit of the party maintained by the D.O.C. went 250 feet of rope, ice axes, first aid kit, emergency rations, extra skiis, extra snowshoes and creepers, compasses, and field glasses. Arrangements had been made at Gorham by the leader, J. K. Sullivan '25, who had preceded the party so that trucks awaited the gang at the station and a dinner was laid at the Mt. Madison House. Four horse sleighs trundled us out to the Glen House in time for a good night's sleep.

Next morning on the Carriage Road, a half-hour's climbing sent wool shirts into packs and cached the useless snowshoes beside the trail. Skiis had been out of the question on the hard-packed snow. With bandanas bound around sweaty foreheads the men bent to a trail that rose higher and higher, not into Arctic Winter but into Spring. At tree line, just over three miles up the mountain we left snow altogether and tramped over dry dirt and rock trail with only occasional patches of ice.

Above, the bare ridges stood snowless against the sky. The great Gulf opened to the right in an emerald pool with darker ravine shadows. Madison, Adams, Clay ranging around the Gulf held only wisps of snow against rocky shoulders that gleamed in the sun.

The air was balmy warm, with just a tingle of fresh melting snow. At the six-mile post we scattered along the rock wall for lunch. As we perched on the valley rim, the barren slopes of the lower ridges in their gray-green moss and lichen stretched away in dipping lawns. Peaks running tier on tier, crest on crest, into the horizon, jutted blue from valleys of misty purple—saffron—rose. Peabody River, far below to the north, shot back a glint of sunlight, and the tiny yellow-orange cluster of Glen buildings were thrust up toward us from their cup of sunlight in stereoscopic sharpness.

The creepers stayed in the packs. The heavy shirts and parkas had no business in air that suggested arbutus and trilium. No equipment, except snowshoes, was left behind, however; mountain temperature is too uncertain to be entirely trusted. Arriving at the Summit from two o'clock on, we basked in the warm sun, melted snow for drinking, and swapped yarns with two Harvard men who came plugging up the cog railroad, and a couple of Boston University students who tramped in from Madison way. The return was a rout of cutting switchbacks and sliding short cuts which took the leader back to camp in an hour and forty-five minutes and the rest of us at varying intervals after.

The mountain had already been conquered. With two days to spend on Carter Range and Tuckerman's we were an elated crew who sat down to the Washington's Birthday party that night at Glen House.

The second day in a driving rain we treked to Carter Notch, quietly aware as we stumbled along in the line of hooded parkas bent to the storm, of the rhythm of tramping, the smell of dozy wood and spicy spruce, the gleam of wet shoulders rising and falling ahead. A toss of wind in the spruces, an eddy of fog poured from the upper slopes that took shape for a moment then faded into mist again. A storm narrows your world and sharpens your senses for what is near. One moves on such a trail in a blowing storm in a comfortable but sensitive seclusion.

Arrival at Carter Notch huts broke the spell. Steaming in the chill stone cabin, we lunched from paper bags, gave up Carter Dome for lack of visibility and returned to Glen House in another wallowing, plunging race. That night, a pile of canoe birch furnished a blaze in the east room fireplace and the outfit sang till they were drowsy.

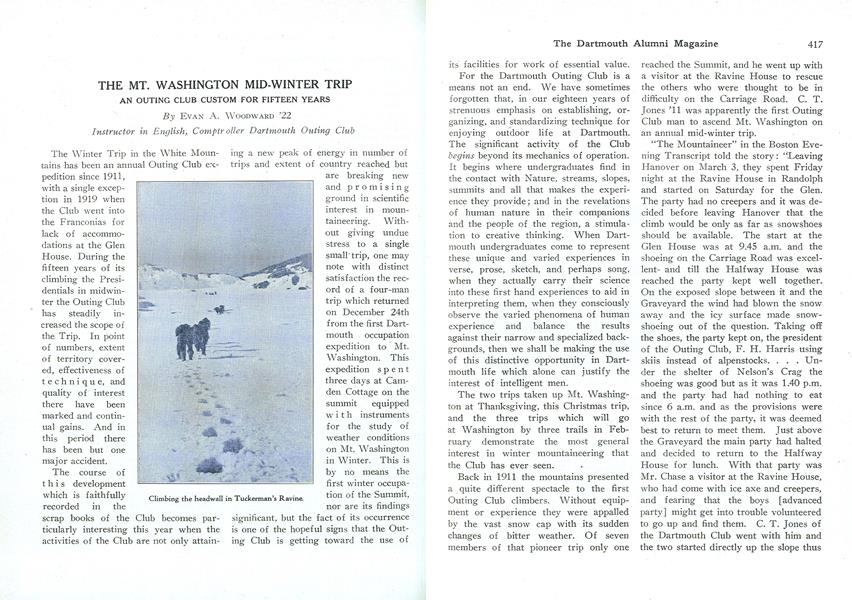

"Blue sky in the west. Ground mist hanging in the valley below Madison. Upper slopes of Washington frost glazed. Summit, in the southeast, white, and rose-tinted by the early sun." Up the road to Pinkham Notch with frequent glimpses of the ravines, Boot Spur, and the Summit. Snowshoes at Pinkham ham huts, and the long scramble up past the Crystal Cascade and Hermit Lake to the floor of Tuckerman's. The Headwall rises from a great snowy bowl with its rounded side sweeping up from the even drifts of the bottom to a rim of ugly rocks. The deep shadow of Boot Spur already creeps across the face . . . Above, the ice cap hangs ominously over the slope. From the boulder-strewn floor tangled with scrub, one sees the tiny black figures spider up the wall of chalk with jerky, hitching motions. . . .

Presently the line of climbers strings up toward the ice cap like the self-projecting dotted line of an animated cartoon. We take up the ascent.

Soft, wet granular snow that opens to kicking steps. Hot sun still beating, pack dragging at shoulders. On, up— kicking footholds and thrusting for handholds. A sense of height, of suspended —clinging;— persistent—crawling rise. Beneath our feet the undertone of running water. Wet snow, then ice with little snow. We reach the jutting shoulders of rock. A crevasse has opened across the wall of snow. We oblique,— steeper now,—barely crawling. Hug the snow and favor that throbbing left knee. What if it should buckle? "Don't look down!" Straight up again now, straight up toward that blue patch of sky. Snow, —still snow. Men ahead disappear. A deep silence in the shadow below, then a yelling—far away. How faintly it comes up! Must be high here. High, and overhanging a clean drop. Bare rocks ahead and browned grass. Twinge of knee and frosting fingers, chunking a boot into packed snow—trying it gingerly —lifting to pry for the next. Off the snow—ground scrub, moss, and rock where the gang is gathered resting. They laugh—suddenly and loudly. One man says, "We have to back down that."

After a split trip to the Summit and Lakes of the Clouds we went down the Headwall again, down more cautiously than up, over snow now glazed to icy crust. One by one as we reached the crevasse, we crawled out over the center of the slide, cast loose our packs, pulled up parka hoods, and launched off to shoot in a smother of fine snow the last five hundred feet. A rush of air, dizzy whirl of landscape, scorching underneath, and one is slowing up amongst the retrievers of lost packs below.

Long after dark the last of the party staggered down to the Glen House, but there was dinner and the return ride to Gorham before the night's sleep.

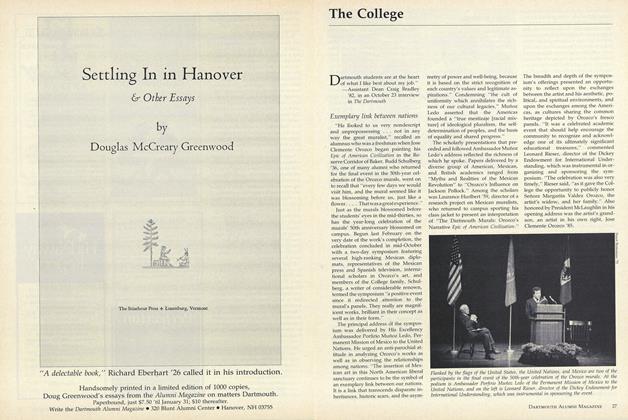

Climbing the headwall in Tuckerman's Ravine,

At the half-way house

On the Carriage Road

Mount Monroe and Lake of the Clouds

Faculty Pond, the scene of much winter activity

Instructor in English,_ Comptroller Dartmouth Outing Club

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1927 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE BUREAU OF PERSONNEL RESEARCH

March 1927 By Harry R. Wellman -

Article

ArticleJOHN LEDYARD AND HIS RUSSIAN JOURNAL

March 1927 By James D. McCallum -

Article

ArticleA Bigger and Better Carnival

March 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1899

March 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

March 1927 By Herrick Brown

Evan A. Woodward '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleTIRRELI MEDAL AWARD

OCTOBER 1931 -

Article

ArticleRoman Trophy Restored by Edward Tuck '62

June 1934 -

Article

ArticleA Reasonable Balance?

January 1976 -

Article

ArticleExemplary link between nations

DECEMBER 1984 -

Article

ArticlePLANS FOR THE "DARTMOUTH MOUNTAIN"

March 1936 By Norman Stevenson '05 -

Article

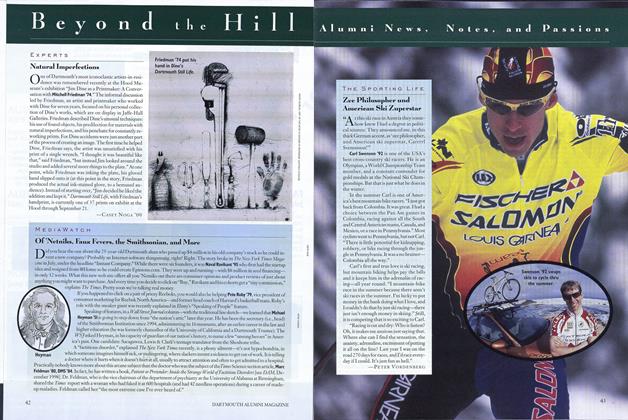

ArticleZee Philosopher und American Ski Zuperstar

OCTOBER 1999 By Peter Vordenberg