Recent complaints emphasizing the immaturity of literary achievement by undergraduates, as revealed by what the critics seem to regard as an increasing poverty in the contents of college magazines, have aroused some interest and provoked some comment. The disposition on the part of the editors of such undergraduate publications appears to be to admit without question the lack of convincing evidence that college students possess any great talents in the way of producing creditable prose and verse, preferring this explanation, as is natural, to the alternative of admitting that their own judgment in selecting from what is offered them is at fault. The assertion is that they know the weeds from the wildflowers, but that all that comes to their desks is poor stuff.

This plaint is reechoed by the editors of the Daily Dartmouth when they say, "We are not producing literature worthy of one of the foremost colleges of the East. It is possible that valuable literary work is going on within the College and that our authors scorn undergraduate publications, but on the whole we are inclined to doubt the literary productivity of our College." The article goes on to cite recent decay in the matter of producing an adequate theatrical entertainment for Carnival week, as a correlative matter. It closes with the thought that if the talent is really there in a dormant state, it might be galvanized to outward manifestations by more cordial recognition on the part of the college public. "Dartmouth may produce good literature when the recognized poet has his choice of senior societies, when the promising short-story writer is rushed by fraternities, when the poet is esteemed and honored by the campus. Then and only then will the production of literature be deemed worthy of concentrated endeavor."

This is a new guise for an old complaint; to wit, that the normal college student does not reveal a disposition to bestow coveted honors on men who excel in other than athletic, or perhaps musical and managerial, activities. It would be folly to say there is nothing in the complaint ; but is one to expect to arouse an artificial, or simulated, enthusiasm to compete with the spontaneous zest which attends achievement in fields in which young men are really and often feverishly interested ? There's nothing pretended about the zeal which college students reveal when they are recruiting their fraternities. They're after men in whom they feel an absorbing interest for one reason or another, and such interest is more readily excited by men who perform in some field which takes a firm hold on the youthful fancy. Besides, there is always the question of good fellowship. If the man whose specialty is some sort of intellectual activity, or the production of poetry, or the writing of short stories for the college magazine, is not courted as others are there is undoubtedly a reason —unworthy, perhaps, and characteristic of youth—but a reason none the less. One recalls the time when the "professionals" in student literary activities were quite commonly, but perhaps unjustly, regarded as prigs and pedants, living in a little world of their own which made little claim to the ordinary boy's attention. It is quite possibly true still—particularly in a day when prose and verse are making such frantic endeavors to be like nothing that ever was before on sea or land.

Nevertheless we incline to believe there is something that can be done along the lines indicated by the Dartmouth's editorial. Students may be led by tact and a vague sense of shame to assess more accurately the worth of literary attainments in their fellows than they appear to have been doing. If, as is admitted, the run of literary work lately has seemed low and unworthy the men of a leading Eastern college, there is small incentive to single out those who produce it for social honors; but if it were known that a really notable reputation for literary work was being built up by some, talented student through his contributions, and if that student were not disposed to play the highbrow in a high hat, there ought to be no question of his recognition in the lines suggested. Sometimes the literary fellers have themselves to blame, in college and out.

Besides, is it quite fair to ask of inexperienced and immature college authors that degree of artistry which one demands when the productions are from men of longer training and wider knowledge, and are offered for sale in a highly competitive market ?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

May 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1927 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

May 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

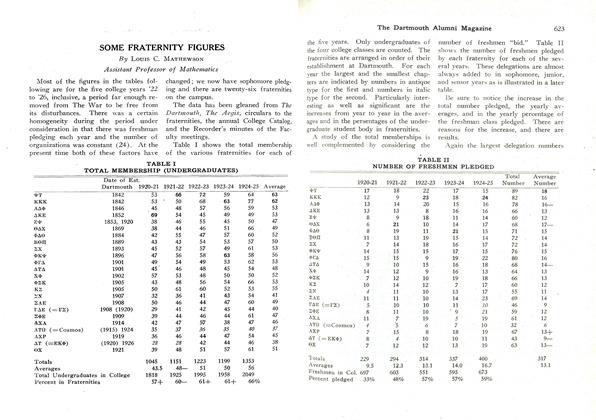

ArticleSOME FRATERNITY FIGURES

May 1927 By Louis C. Mathewson -

Article

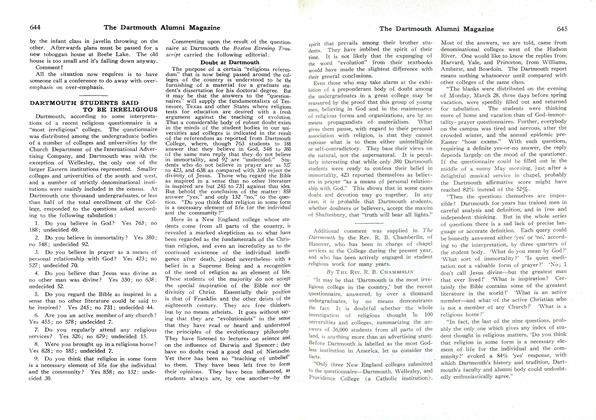

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS SAID TO BE IRRELIGIOUS

May 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1927 By Herrick Brown

Article

-

Article

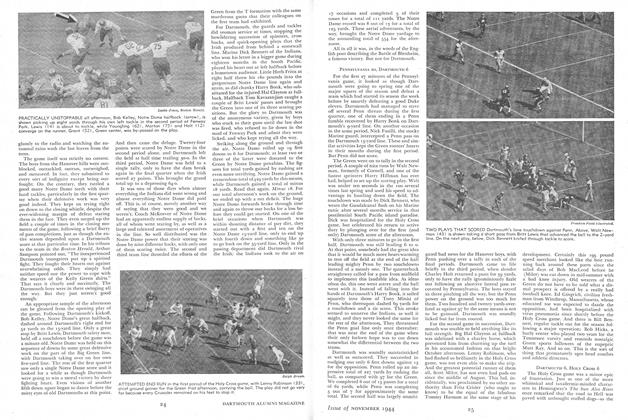

ArticleDartmouth-in-Portrait

November 1944 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Dinners

April 1949 -

Article

Article'58 Alumni Fund : $455,301

OCTOBER 1958 -

Article

Article1985

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Juliet Aires Giglio -

Article

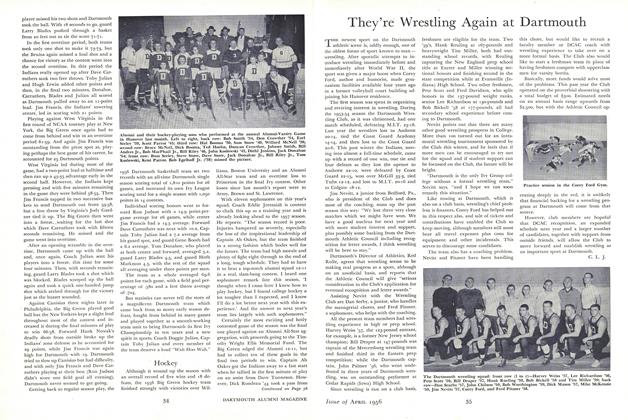

ArticleThey're Wrestling Again at Dartmouth

April 1956 By C.L.J. -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH TWO YEARS PRECEDING THE CIVIL WAR

February, 1926 By John Scales '63