DARTMOUTH UNDER THE CURRICULUM OF 1796-1819

Professor of History

Webster's keenest interest in college lay in history, English literature and composition. He also kept himself posted upon political affairs, read the newspapers, and did a good deal of general reading including philosophy. Greek and Latin he studied for at least three years in college, taught after graduation, and pursued with zest to the end of his life. In mathematics, Webster got what one of the best students in college would gain from three years of Arithmetic, Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, Conic Sections, Surveying, and Mensuration of heights and distances.

There is nothing to substantiate Lodge's false portrait of "the indolent Webster," not a fine scholar, who lacked "zeal for learning," "knew no Greek," had "less than a smattering of mathematics," Lodge, violating the evidence he nominally cites, copies here as elsewhere the partisan and unreliable Parton, and reproduces the bitterness and inaccuracy of the political enemies of Webster in 1850. The testimony of Webster's fellow students (to which Lodge refers) contradicts the unreliable biography and confirms other evidence that the lack of fine scholarship and zeal for learning is not in Webster but in Lodge.

His college mates repeatedly and uniformly recorded their recognition of Webster as "our ablest man," "the best all-around mindand recognized the high degree of his intellectual power and performance as shown not only in college leadership and debating, but also in writing and in classroom. With consistency and some definiteness eleven class and college mates (corroborated by as many more of his later scholarly friends, like Ticknor, Choate, Felton, Everett) witness to Webster as being "peculiarly industrious," working with great intensity and rapidity, and remembering accurately so that in place of spending three or four hours on a textbook, "as was the case with most of us," he would "procure other books on the same subject for further examination and spend hours in close thought, either in his room or in his walk, which would enlarge his views, and might at the same time, with some, give him the character of not being a close student." There is unconscious irony in this testimony of Bingham, his Exeter classmate and Dartmouth room-mate, as to the inability of a certain type of mind to recognize the scholarly quality involved in "close thought." John Whipple of Providence says Webster told him he "had trained his mind as he would his body to accustom itself to greater tasks, but not to overload it; to work at his utmost and then recreate. Into any mental occupation he put all his power, and when mental vision began to be obscured, he ceased entirely and resorted to amusement." "When a half hour or an hour at most, had elapsed, I closed my book and thought over what I had read"so much as I read I made my own," these were Webster's own descriptions of his college method of work. One other habit he confessed was of being very careful to stop talking at the point where his knowledge ceased. "Mr. Webster was remarkable for his steady habits, his intense application to study, and his punctual attendance upon the prescribed exercises," said Roswell Shurtleff who as both fellow student and tutor had double opportunity to judge him.

Webster's statement, "I have worked for more than twelve hours a day for fifty years on an average" (made to Professor Sanborn in 1846) would cover both Exeter and Dartmouth student days. Without undue reliance upon this sweeping generalization, Webster's habits of long, hard, daily work are confirmed by the amount accomplished, the ample testimony to his early rising, late working, and the college habits of his day,—with chapel at daylight, and three or four hours devoted to a lesson by "most of us," according to Bingham. "My college life was not an idle one. What fools they must be to suppose that anybody could succeed in college or public life without study." Such statements of Webster, amply corroborated, relegate the legend that he "did not study much in college" to the limbo of false and long discredited legends like that of his tearing up of his diploma, both alike contradicted by Webster and contemporaries, and entirely unsupported by evidence.

The following results seem in part at least attributable to the college training of Webster and Choate; recognition of gaps in their knowledge; widening intellectual interests; abiding satisfaction in quenching their thirst for learning; appreciation of the finer things in literature and life; power of clear thought and speech; habits of hard, concentrated work. The lack of work in natural science was partly recognized and met by work in the Medical School founded during Webster's undergraduate days and markedly stimulating under the lead of two great pioneer teachers, Nathan Smith and Lyman Spaulding. Webster was one of 18 men in his class of 32 in Junior Year to register in the Medical School. Choate one of 25 in a class of the same number to register during Junior or Senior year. Whether they heard lectures in chemistry or general medical subjects there is no convincing evidence available.

In 1816, Webster recognized that "the manner and system of education in this State are necessarily much confined;" but added in his frank letters of advice to his nephew Haddock, "after all, progress in knowledge depends less frequently on the opportunities enjoyed than on the use made of them." What Webster meant by such use, he points out by counselling Haddock (then a divinity student at Andover) not to go back to Latin grammar, but "to read the whole of Cicero and Livy and Quintilian, and the other great writers." "Latin should be learned for the sake of the good things which are in Latin. It is folly to learn a language and then make no use of it." So Webster and the two Choates while apparently lacking courses formally labelled history, utilized for historical purposes their classics and courses in law and government. Directly after graduation, while studying law, Webster read Caesar, Sallust, Cicero and Juvenal; went through Saunders Reports; "and put into English out of Latin and Norman French, the pleadings in all his reports." Both Webster and Choate to the end of their lives (even as Senators in Washington) read and delighted in the classics constantly and used them as instruments for training in thought and speech.

In 1814, Webster had written Haddock his appreciation of the relation between Geography and History, incidentally commenting on the curriculum and its interest during his own sophomore year. "You are now, I think, in your Sophomore Year. I recollect that year was an interesting one to me from the studies that belonged to it. I suppose the course of studies is since that time a good deal altered ; but it was then Geography, Logic, Mathematics, etc. As we had been before confined altogether to Latin and Greek, the other pursuits in addition to their importance possessed the charm of novelty. Geography especially is an interesting study. It is an indispensable preliminary to history." "I would advise you never to read the history of any country, till you have studied its geography." "You must have before you maps of the country." Webster's historical sense he further developed "at an early period of life" by recourse to two "sources of information," the English statutes, and the proceedings of the law courts. "I acquainted myself with the object and purpose and substance of every public statute in British Legislation," "not so much for professional purposes as for the elucidation of the progress of society." "We want a history of firesides," was his felicitous description of the social history which we still lack. His address on "The Dignity and Importance of History," confirmed as it is by the competent testimony of Professor Felton of Harvard, shows Webster continuing through life, like Choate, college habits of getting history from the sources.

What Rufus Choate got out of his undergraduate days was told in his delightful way in an intimate letter to his son then in college. "My college life was so exquisitely happy that I should like to relive it in my son. The studies of Latin and Greek,Livy, Horace, Tacitus, Xenophon, Herodotus, and Thucvdides—had ever a charm beyond expression, and the first opening of our great English authors, Milton, Addison, Johnson, and the great writers for the reviews made that time of my life a brief, sweet dream. They created tastes and supplied sources of enjoyment, which support me to this hour." Dr. Boyden of Beverley, a classmate, says of Choate. "Before the end of the first term he was the acknowledged leader of the class and he maintained that position until graduation without apparent difficulty, no one pretended to rival him." "His talk was of eminent scholars of other countries and of former times and they seemed the object of his emulation." "When sport was over he turned to his studies with avidity."

Choate's extraordinary power to win devotion for himself and the things he loved made him an inspiring teacher. Professor Brown's statement that Choate's year as tutor was "one all sunshine" is especially felicitous in view of the fact that Helen Olcott was part of the sunshine. Admiration for Choate's ability increases as one realizes that he not only led his class but also found time to win the most charming girl in town.

Four colonial buildings fortunately still remain as a visible framework for Webster's and Choate's college life. In the Eleazar Wheelock Mansion house of 1773 (now the Howe Library), Webster would have "made his bow" to John Wheelock and been admitted to college. In the Webster cottage on North Main Street built 1780 he roomed his Senior year. In the Olcott house (built by Professor Ripley, 1787) Webster passed his first night in college; and here Choate wooed and wedded Helen Olcott. Like Helen, the house has now changed its name to "Choate." In the adjoining "College Church" of 1795, (of which all professors and many tutors were members to 1819) Webster and Choate both received their degrees; Choate pronounced his valedictory at the Commencement of 1819, attended by Webster ; and in 1853 delivered his Eulogy (in Everett's judgment, unequalled in America) worthy of Webster and himself and their romantic "friendship of scholars." These two simple white structures, typical of the time and taste of Webster and Choate and the colonial college, have together probably sheltered more famous men than any other adjoining buildings in New England. With Webster Hall flanking the other corner, they furnish unique and inspiring approach to a new library.

What students read in the old library in Dartmouth Hall is a fascinating study. The book most frequently drawn during 1774 to 1777 when the records are available, was Rollin's Ancient History (which Webster read as a Sophomore), charged on the librarian's records no fewer than 92 times in three years, with Pope's Works 44, and Locke, Human Understanding, 32 times. The other books, in order of frequency of drawing by students, were: "The Fool of Quality;" Witsius' Economy; Baxter, various titles; Martin's Philosophy; Edwards on the Will; Ward's Mathematics; Watt's Logic; Addison; Pilgrim's Progress; Locke's "Government;" Holmes' Rhetoric ; Butler's Analogy. Robinson Crusoe was drawn only three times. Unfortunately there is for Webster's day no record of books drawn from the library. The college does possess three sources of information: the manuscript list of books in the library 1775 ; the books which came from Eleazar Wheelock to the library after his death in 1779; and a list of purchases from 1793 to 1820. This enables us to know some of the books available to Webster and Choate; though these lists do not cover purchases between 1779 and 1793, or the two Society libraries of Webster's time, both available to him. These three libraries contained between 3000 and 4000 volumes in Webster's, day, as nearly as may now be estimated from books actually bought annually and the number when the first catalogues were printed in 1810 and 1812. Samuel Smith of 1800 remembered the "library" as containing about 4,000 volumes. In Choate's time the college library possessed about 4,000 volumes; the two societies about the same number; in all, about twice the number available when Webster was in college.

Webster's letters show him "dozing over a musty volume of Rollin's" [Ancient History], Sophomore year; and during Junior year reading Mallett do Pan's History of the Destruction of the Helvetic Union, and keeping up his interest in Napoleon. Fond of books from childhood; always familiar with the Bible; getting the Spectator and Addison from a small circulating library; having access to so few books that he "thought they were all to be got by heart," he could repeat the greater part of Watt's Psalms and Hymns, and Pope's Essay on Man "from beginning to end." His early habit of swift concentrated reading is illustrated by his statement that Don Quixote he "read through at a sitting without laying the book down for five minutes." The year following graduation, while teaching school at Fryeburg and copying deeds to help Zeke pay his college bills, Webster read John Adams' defence of the American Constitutions, Mosheim's Ecclesiastical History, Goldsmith's History of England, Blackstone's commentaries, Pope's works, the Spectator and Tatler. For the next two years, "my principal occupation with books, when not law books, was with the Latin classics." The "indolent" Webster also found time to learn French and make use of this and his Latin as tools in legal history; and to read "Ward's Law of Nations, Lord Bacon's Elements, Puffendorf's Latin History of England, Gilford's Juvenal, Boswell's Tour to the Hebrides, Moore's Travels, and many other miscellaneous things," besides reading Hume, and Vattel's Law of Nations. Webster's college habit of wide and thoughtful' reading and long hours of work he carried through life.

During the decade 1790 to 1800, in which fell Webster's undergraduate days, Dartmouth was graduating 36 men annually,.a larger number than any other American college save Harvard. The average number of undergraduates in the Dartmouth of Webster and Choate was 141.

The curriculum shows marked similarity to that of Harvard, in the "Laws of Harvard College" for 1814, 1816, and in the catalogues of 1819 and 1820. Limited as the curriculum was, especially in natural and social sciences, the course and method of study in combination with the other conditions then prevailing had certain admirable features likely to develop native ability.

The students really cared for an education, and had definitely prepared for it. They had to face an entrance examination conducted by professors who were to test them and teach them in college. Continuity for six to eight years was secured by continuing in college the four subjects of the preparatory school; Greek, Latin, and Mathematics for three or four years, and English throughout the college course. A student therefore had to get his present work in order to go on with his future. He looked forward to some degree of mastery of subjects studied through both school and college. He could not pick and choose, and when he found he could not do one soft thing find another softer. The vice of smattering and scattering would seem to have been largely avoided, especially in Greek, Latin and Mathematics, where a considerable degree of accuracy and precision would have been called for in Choate's senior year, his tenth in the study of Latin. The sound principle of application was apparently sought through mensuration, surveying, navigation; and a taste of natural science through physics and astronomy, and chemistry in Medical School or college. That Dartmouth some how not only led men to the fountain of knowledge but also gave them intellectual thirst and the power to satisfy it, is suggested by Webster's growing interest in natural science. From his interest in geography in connection with history, he went on to a keen attention to physical geography. On his voyage to England he learned to take observations. Geology he studied somewhat carefully on his journeys; and had specimens arranged in strata to visualize the order of nature about which he was reading. Felton adds that he read and meditated on Humbold's Cosmos, and that "with ichthyology he had not merely a sporting, but a scientific acquaintance."

Webster's and Choate's precision of thought and beauty of speech were aided by their lifelong, discriminating reading of the world's masters. No one can read their private letters, and public speeches without recognizing men who see realities hitherto unseen, and then reveal their vision in words of artistic precison. Webster was a poet in politics in this sense. He created in men's minds the vision of things that were not yet but had to be. The young men of the Civil War tell us they volunteered with his words on their lips, familiar but sacred as those of the Psalmist; and that on lonely sentry duty in seceding states they paced back and forth repeating: "Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable." The flash of insight which, from the drum-beat on the ramparts at Quebec, caught the vision of unbroken world empire, Webster revealed to others in his picture of the British Empire: "A power which has dotted over the surface of the whole globe with her possessions and military posts, whose morning drum beat, following the sun, and keeping company with the hours, circles the earth with one continuous and unbroken strain of the martial airs of England." Choate's power of voicing what he saw is illustrated in his characterization of the ruthlessness of John Quincy Adams. "He has withal, an instinct for the jugular and the carotid artery as unerring as that of any carniverous animal." Such men not only appreciate beauty; they create it.

With growing critical sense, Webster and Choate pursued their reading of Milton, Addison and the ancient classics, from college to the end of life. Choate planned a translation of Demosthenes' "On the Crown"; Webster of Cicero's De Natura Deonun. "Cicero, Virgil, Horace, Livy, Sallust and Tacitus were his (Webster's) frequent companions, and constituted the solace and delight of his leisure from official employment. He read their works not only with a profound understanding of their aims and scope, but with a delicate discrimination of their manner and style. Shakespeare, Milton and Gray were household words." "With rare felicity of judgment and exquisite delicacy of taste, he discriminated the minutest shades of beauty in the structure of their sentences, and the choice and arrangement of their words." This testimony of Webster's intimate friend, the scholarly Felton, Professor of Greek at Harvard, is supplemented by the illuminating pages in Choate's Eulogy devoted to Webster's college life, and by Webster's delight in the ancient and modern classics, in Locke, the philosophers and historians. "These were the strong meat that announced and began to train the great political thinker and reasoner of a later day." Choate's own classical train ing and scholarship were even better than Webster's; and his letters and journals witness his daily delight in the classics and his discriminating use of them in his training in expression.

Three unpublished letters of Rufus Choate's younger brother, Washington, reveal the intellectual tastes of a Freshman and Sophomore in 1820. Ridiculing the superficiality of the study of modern language where men learn a little grammar and a few hundred words but never the language, he says: "There is in brevity and in truth no such thing as a translation." What he felt worth while was to read and understand "the works of the immortal poets, orators, historians, and philosophers of England, Greece and Rome." In response to his brother Rufus' criticism that he had been reading poetry too rapidly, this Sophomore of 1820 says he had, in the "first four and one-half weeks of his sophomore year, read only Terence, Plautus, four comedies, Catullus and some 30 or 40 pages of Ovid. All I have read in this time might be put in three twelve mo. vols." Not only had he read these authors, but he wrote critically of their plots, characters and style, incidentally remarking "that he had never laughed so loudly or long over any book since reading Don Quixote as he did over Amphitryon." Millot's History of Rome and St. Real in French he was reading "from the 3 o'clock recitation till prayers." "For English books I have Alison (on Taste), Taylor's Sermons, Boetius, Tales—etc." "I shall read, if I have time before I go home. Ovid, Tibullus, Propertius, and then I think, though out of course, Brutus, DeAmicitia, and De Senectute, and carry home some other of Cicero's philosoph ical works." "Schlegel I have read with attention and have now about me Spencer's and Coleridge's Biography, Literary, and Edinburgh, and Quarterly Reviews. The Edinburgh review of Schlegel is I think among the best I ever read and has given me after repeatedly and most carefully perusing it, a clearer view of the distinction between the romantic than I could ever obtain before. The Quarterly Review of it is good for nothing."

The references to Schlegel and Coleridge are of singular interest, for they connect Choate and Dartmouth with the profound scholar and teacher, James Marsh, who helped to introduce Coleridge to Emerson and the Transcendentalists of America. Marsh was on somewhat intimate terms with the Choates for two years tutor of Washington, and for three years fellow student or fellow tutor with Rufus, with whom he kept up later friendship and correspondence. Now it was in just these years at Dartmouth with the Choates that Marsh began his revolt from the old system of philosophy to that of Coleridge whom he later edited and whose ideas he embodied in the reorganized curriculum of the University of Vermont of which he was President. His educational ideas spread thence to the middle west. A scholar who profoundly affected American philosophy and education, Marsh was one of the nine college presidents bred in the challenging days of Rufus Choate's undergraduate life.

Good taste in literature may well have been aided also by the work in rhetoric, and the Belles Lettres. The evident lack of a provision in the curriculum for the English classics seems to have been made up by students in their reading, if one may judge from letters during and after college and by the books in the college library, and those selected for their own literary societies and purchased by themselves, several hundred annually with their own hard-earned money. With few books and few distractions, students read with care real masterpieces of thinking and expression, and themselves thought, talked and wrote about what they read. Clear thought and plain speech were likely to be developed through four years' continuous training in writing and speaking, with college required work supplemented by voluntary tasks in the weekly meetings of the literary societies. Common interest in the same intellectual things and common ground for debates were made possible by the fact that the same work was done by all the men in every class.

It must be admitted that students who had little interest in literature, mathematics, philosophy, or law, found the work irksome. "By the time one lesson is got another rises up before you which will take away all one's appetite for play, idleness, or any other amusement." This lament in the diary of Freshman Smith, contemporary of Washington Choate, closes with a bed-time philosophy worthy of Samuel Pepys. "William Clark says that we are enjoying ourselves now the best of any time in life—forgive him I pray this sin for can it be that this is our best days O no surely not go to bed 10" The course tended to discourage youth from coming to college for social rather than intellectual purposes. Modern education in dealing with this type has trusted too much to purgatives, and failed to keep pace with progress in pre ventive medicine. Whatever the reason, continuity was a characteristic of the undergraduate as much as of the curriculum, under which actually a larger number graduated than had entered. In the Sophomore year there was an average gain of ten, offset by a loss of only five during Junior and Senior years. The average class entered 29 men and graduated 34, a net gain of nearly 20 percent, as contrasted with a modern loss of over 40 percent between freshman year and graduation. Moreover, in the average class of 34 graduates, 31 continued in some form of professional study. There was, furthermore, an unusually large proportion of graduates (over one fifth) who achieved distinction.

The college of 141 students and four or five college officers constitute a challenge to trustees, faculty, alumni and 2,000 undergraduates of the "'Liberal College" of a jazz and prohibition era. Doubtless the inescapable entrance and curriculum requirements facing Webster and Choate would not do for the modern more delicately nurtured and financially better prepared "undergraduate." The student who thinks it "democratic" to call Dartmouth a "school," his carnival guest as "the woman," and with quite unintended humor says he comes to college, "because I was not and am not ready to go to work," could not and would not meet the requirements of Even more than the present-day forty percent would fall by the wayside, exhausted by the continuous strain of accurate firsthand knowledge and "close thought" demanded by continuous and cumulative work in Greek, Latin, Mathematics. Philosophy, Theology, and Law. The problem before us is not one of imitation but whether out of our own educational development we have gained enough clear thinking and creative power to construct both an ideal and a practical curriculum for students of all kinds of previous conditions of servitude from over a thousand schools, from intellectual byways (without hedges) all over the land. Can this well-behaved, externally well-equipped, courteous, lovable modern youth, socially sophisticated and intellectually naive, conscious of the limitations of his elders, be awakened to his own? Can his oft-times mediaeval lack of intellectual curiosity and readiness to accept second-hand information, his "markchasing" in college, and aim of "selling" something after college be replaced by the finer ideals dormant within him? How shall we attract poor boys, and sons of farmers, ministers and mechanics (whom Professor Woods has shown so desirable) and not be overbalanced by the wealthy ?

Can we develop, not a curriculum of 1796, but one that will fit the needs of today with something which will give continuity, clarity of thought and speech, love of beauty which is itself a beatitude, satisfaction with only the best, and dissatisfaction with the lower levels of life, some abiding interest in literature, some sources of permanent enjoyment, some power to be of use to the commonwealth? Can the spark hidden within essentially high-minded youth be warmed into a flame that shall light them to the joyous adventure of life, as went of old the men of the renaissance, the "gentlemen adventurers," the pioneers, to discover the unknown, achieve the hitherto impossible, do something better than it has been done before ? This would be an adventure in education worthy alike of the pioneer spirit of Eleazar Wheelock, founder, and President Francis Brown and Daniel Webster, refounders of Dartmouth.

The longer and more closely one studies the college of a given period, the less inclined he is to account for its greatness on the basis of a single factor, or even to assign with precision the relative importance of curriculum, college life, teachers, or students. It was the happy combination of excellence in all these that produced the result. The balance between intellectual and social "activities" finds felicitous expression in Choates two descriptions of his college life: "studies which created tastes and supplied sources of enjoyment which support me to this hour "the friendships of scholars, grown out of a unanimity of high and honorable pursuits." Fraternities, religion, recreations, earning money through school-teaching, reinforced rather than weakened intellectual life. The wellvertebrated curriculum with its continuity, and training in clear thought and plain speech was suited to the type of students,ambitious, aiming at professional and public life, attracted by the same sort of work they had done in preparation, courageous enough to face a test in it before entering.

"Short commons and industrious habits of study with hardworking teachers laid firm foundations." "Ripe teachers made ripe pupils." Such were the ripened conclusions of Nathan Crosby as to the college of Choate's day and its faculty,President Brown, Roswell Shurtleff, Ebenezer Adams, James Marsh, Rufus Choate. These teachers and those of Webster's day, were deservedly appreciated for their "amiability," hard work and devotion. Besides brains and schol arship, all these men had more training than appears at first sight. In the backbone of the curriculum, the classics, they had received eight, or in Choate's case, ten years' training. Some hard-earned wisdom most of them had gained in winter school teaching. All had to supplement college education by some graduate experience or training. Not one of the thirty-four teachers from 1770 to 1819 entered upon college teaching directly upon graduation. Every one had been out of college at least one year, the majority two or more years, teaching, or studying divinity, medicine, or law. Bailey, tutor of Choate, had studied divinity, and read law with Webster. Seven had taught under the President's observation in the Indian School, not a bad preparation for teaching Dartmouth undergraduates of that or much later days! Seven studied divinity under members of the Dartmouth faculty. Four years was the average period of ripening between graduation and college teaching. Of Webster's teachers each of the permanent staff had taught a score of years. Wheelock had served in the Legislature and as Lieutenant Colonel in the Revolution, and was deservedly commended for his wisdom in selection of teachers. Smith was trained in divinity, experienced as pastor, the author of classical text-books, a scholar of repute, recipient of honorary degrees from Harvard, Yale, and Brown. Bezaleel Woodward had been trained in divinity, was an acceptable preacher and Elder, versatile political leader, prominent in the Revolution, a useful county judge, active in all town and church affairs and treasurer and (like Wheelock and Smith) a trustee.

The fact that two thirds of the teachers under the curriculum during the first half century of the college studied divinity suggests both a type of work and a type of men. The work included not merely added training in ancient languages, but also in writing and in power of human approach and appeal. It was the best kind of graduate work then available and supplied something often lacking today in graduate training and college teaching,—a combination of sound scholarship with devotion and sense of pastoral care. It was utilized to advantage by the type of teacher who saw in teaching the cure of souls as well as the care of minds. The genuine and attractive Christian character of teachers who recognized the spiritual element in scholarship was likely to kindle similar qualities of loyalty, devotion, courage, hard work and human helpfulness in their students. The fundamental purpose of the college, "civilizing and christianizing," was an essential element. No analysis of the causes of the loyalty and success of the first half century is adequate which fails to recognize the power of this religious element.

As to the type of men bred under the curriculum of Webster and Choate's day there are some rather striking evidences. Among the graduates under the 1796 curriculum, at least one in five may be said to have attained distinction. Distinction is evidently not a thing to be measured by a yardstick or with scientific precision, for there are too many imponderable elements. The work of many a country pastor or teacher deserves distinction which it never receives. On the other hand it might fairly be questioned whether a college professorship is a mark of distinction. In such cases it might be safer to follow the practice of Webster's debating society, and put down: "Answer. Conditional." Taking figures for what they may be worth, we find among the 877 graduates in the classes from 1797 to 1822 the following: One justice of the Supreme Court; three cabinet officers ; seven United States Senators; eight Governors;" twelve Judges of State Supreme Courts; nineteen members of Congress; seventeen College Presidents; twenty-nine college Professors; eightyfive recipients of honorary degrees of D.D. or LL.D. After compiling this list of somewhat obvious distinctions, with its evident incompleteness and probable inaccuracies, the writer turned to the summary in Chapman's invaluable Sketchesof the Alumni. of Dartmouth College, and. found the basis of distinction there almost identical. For purposes of comparison with other periods of the College the figures may be of some use, until some better basis and more exhaustive research are available. A comparison made by the writer shows a larger percentage of men of the enumerated kinds of distinction under the old curriculum, than since 1819. It is so difficult, however, to weigh such imponderables and to make allowance for changes in kinds of distinction, that it is probably safer to allow the reader to "roll his own" figures.

In politics, and in college administration (two fields not so far separated in the days of the Dartmouth College Case!), the graduates of the old-fashioned classical curriculum most frequently achieved distinction. Although the graduates of 1796-1822 comprised less than a quarter of the alumni, they furnished one third of the total number of college presidents, over a third of the United States Senators, nearly a half of the members of Congress, and nearly two thirds of the cabinet officers, contributed by the total number of Dartmouth alumni. The only group of distinguished men where there was a smaller percentage under the 1796 curriculum than for the entire period was that of college professors. This fact at least removes from our distinguished list the odium of being built up on mere professors.

The interest in the strenuous legal and political life of the time was general in the days of both Webster and Choate; but it is reasonable to suppose that this interest was strengthened by the virility of their college life and by the very strenuousness of the curriculum and its admirable preparation for public service of that generation. Choate, for example, ambitious as a Sophomore for graduate study in "a foreign University," becoming actively involved in the legal vicissitudes of the College Case and greatly impressed by Webster's legal and oratorical power, turned from his ideal of a college professorship to what had seemed to him "the tiresome routine of a special pleader's life."

Under this curriculum were bred such scholars, administrators, lawyers and statesmen as President Francis Brown, Sylvanus Thayer, (reorganizer of West Point and founder of the Thayer School) James Marsh (President and reorganizer of the University of Vermont, and forerunner of Emerson and the Transcendentalists), George Ticknor (author of the History of Spanish Literature and Professor of Spanish at Harvard), George Perkins Marsh (philologist and diplomat), Webster, Choate, Joel Parker (Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of New Hampshire and Royal Professor of Law in Harvard, one of half a dozen great jurists and law teachers of his day), Levi Woodbury, and Thaddeus Stevens. Nor were there wanting a host of the humbler servers of mankind who escaped notoriety- and the statistician; devoted pastors in villages made more wholesome through unassuming, highminded leadership; scores of teachers in schools; and missionaries notable for the range as well as devotion of their Wheelock-like work in "civilizing and Christianizing." Drop the plummet where you will, it reveals quiet depths of intelligent service.

There were, of course, limitations, weaknesses, and some drab passages, in College and in the, curriculum with its inescapable, serious and continuous hard work. A recent road map with unintentional humor thus describes the college. "Here is Dartmouth College all granite and macadam!" In the earlier stone age, a century ago, the granite of New Hampshire happily did not clog the student's brains, but, true to the latter part of the college motto, contributed to "make his paths straight." The finer qualities were not, however, lacking. Webster's own accounts of his college and later reading, Choate's Journals; the surprisingly comprehensive libraries of both men, the testimony of competent witnesses, show these brilliant but wellbalanced and influential undergraduates reading the best literature with discrimination, acquiring a genuine taste for fine things, developing clarity of thought and power of expression, making their widened interests serviceable to themselves and others, and continuing to do so throughout life.

The college and its curriculum certainly tended to develop public mindedness as well as intellectuality. Nor was college life all seriousness, but, rather, one of happy, wholesome, stimulating friendships and ambitions which led each of these two scholarly statesmen, jurists and orators to return at every opportunity to "endeared Hanover,'' "dear old village, and to wish for a son a "college life as exquisitely happy as my own."

It does not solve our problem to say that such men as Webster and Choate were exceptional. The obvious query remains. Is Dartmouth attracting and educating the exceptional men of today?

The new Fireplace on Moosilauke

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1927 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

May 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

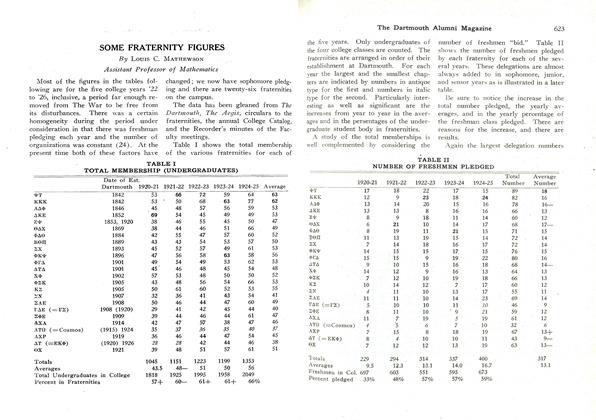

ArticleSOME FRATERNITY FIGURES

May 1927 By Louis C. Mathewson -

Article

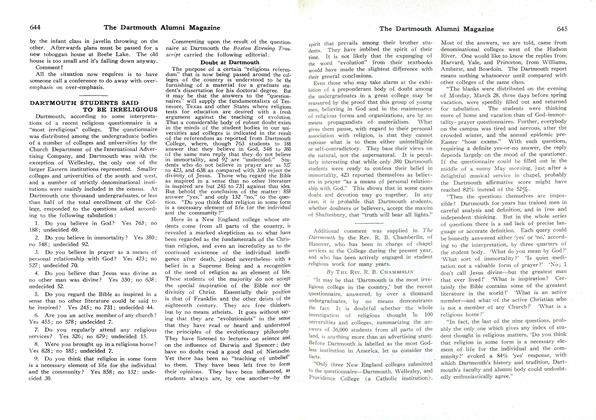

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS SAID TO BE IRRELIGIOUS

May 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1927 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

May 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

Herbert Darling Foster '85

Article

-

Article

ArticlePHI BETA KAPPA BANQUET

April, 1912 -

Article

ArticleForeign Fellowships Open

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleSTAFF PROMOTIONS

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

March 1981 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

December 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticlePURE DEMOCRACY AND THE COLLEGES

January 1922 By HOMER EATON KEYES '00