(From The Boston Herald) The letter of Dartmouth's president proved more of a surprise to the general public than to the leading university officials of the East. College authorities have been sitting up nights with the football problem. They have been exchanging views. Whether any program has been agreed upon, any schedule for a campaign to be started by this rather startling manifesto from Hanover, we shall learn in due time. But there is little likelihood that this pronouncement was put forth as a "feeler" and issued without premeditation. It is timed at the period of the sag between the ending of the season of winter sports and the opening of the spring. It comes from an institution, as was shrewdly remarked by somebody at Yale, which does not have a $20,000,000 endowment campaign under way. It represents the views of the executive of a college which ranks right at the top in football. It is entitled to respectful attention and is bound to be widely debated, which is one of the things President Hopkins most desires.

What would be the effect of the adoption of his proposals ? Would it dilute the enthusiasm" of the outside world for football, empty the colossal stadia of their cheering thousands, end for good the colorful spectacles of each recurring November, take away the income which supports in large measure all other forms of sport, deprive the colleges of millions of endowment which their alumni and friends shower into their treasuries? Would the multitudes refuse to pay to see such games as President Hopkins recommends ? There is no end to the questions raised by his proposals. Their discussion inevitably leads to the consideration of the whole value of football as a. sport and to the relative place of football in the schedule of the undergraduate.

President Hopkins believes in the game. The meatiest single sentence in his statement is this: I do not want to see it exalted to its ruin by uncomprehending forces outside the college life "or do I want to see it stifled to its death by exasperated forces within." He sees, what many another student of the situation perceives, that the sport has become an enormous business overshadowing almost all other forms of college activity, and that the men who make the team and great numbers of students who do not reach the varsity, live through many months of the year by and for football and nothing else, under discipline second in efficiency only to that of war itself. How to save the sport and at the same time cut away whatever damages the students as individuals and the institution as a whole, is the question to which President Hopkins addresses himself.

Something needs to be done. The president well says that as yet little has been proposed except either to let the game alone and take what comes, or to annihilate it. He favors neither. He wants football a game, and not an ordeal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

May 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1927 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

May 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

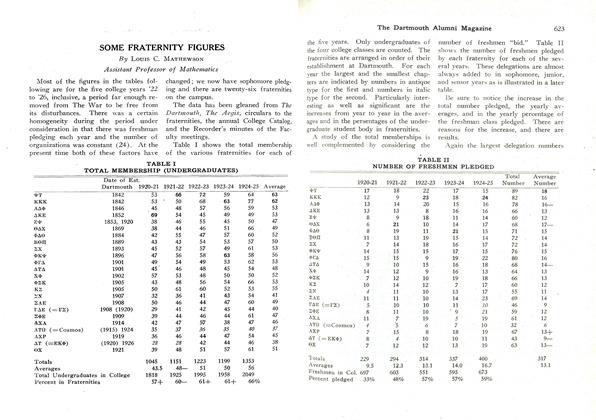

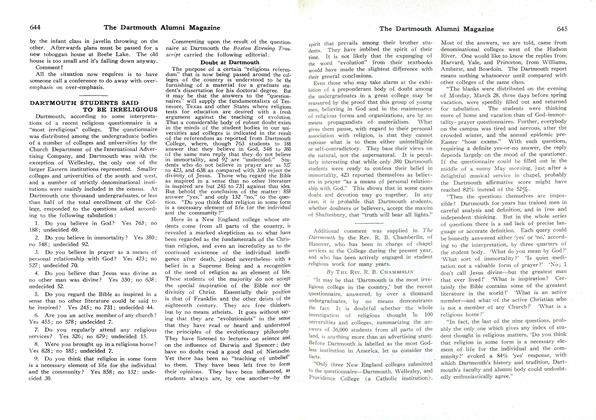

ArticleSOME FRATERNITY FIGURES

May 1927 By Louis C. Mathewson -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS SAID TO BE IRRELIGIOUS

May 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1927 By Herrick Brown

Article

-

Article

ArticleFew Freshman Failures

MARCH 1930 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

December 1956 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal Dartmouth in the New Deal

February 1934 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1953 By DICK MAY '54 -

Article

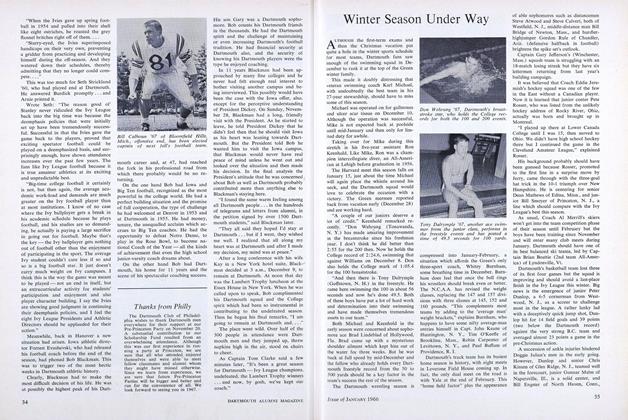

ArticleWinter Season Under Way

JANUARY 1966 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22