Professor of History at Dartmouth College

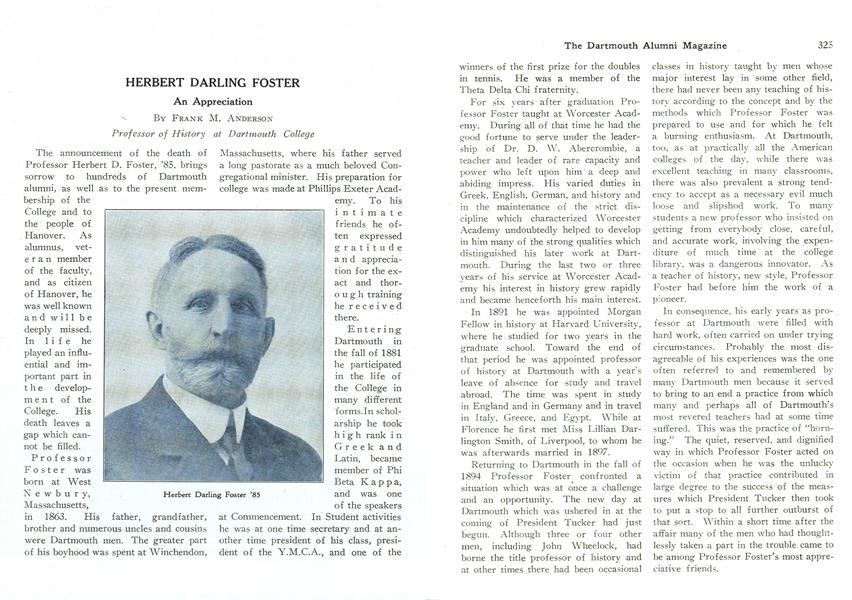

The announcement of the death of Professor Herbert D. Foster, '85, brings sorrow to hundreds of Dartmouth alumni, as well as to the present membership of the College and to the people of Hanover. As alumnus, veteran member of the faculty, and as citizen of Hanover, he was well known and will be deeply missed. In life he played an influential and important part in the developme nt of the College. His death leaves a gap which cannot be filled.

Professor Foster was born at West Newbury, Massachusetts, in 1863. His father, grandfather, brother and numerous uncles and cousins were Dartmouth men. The greater part of his boyhood was spent at Winchendon,

I Massachusetts, where his father served a long pastorate as a much beloved Congregational minister. His preparation for college was made at Phillips Exeter Academy. To his intimate friends he often expressed gratitude and appreciation for the exact and thorough training he received there.

'Entering Dartmouth in the fall of 1881 he participated in the life of the College in many different forms.In scholarship he took high rank in Greek and Latin, became member of Phi Beta Kappa, and was one of the speakers at Commencement. In Student activities he was at one time secretary and at another time president of his class, president of the Y.M.C.A., and one of the winners of the first prize for the doubles in tennis. He was a member of the Theta Delta Chi fraternity.

For six years after graduation Professor Foster taught at Worcester Academy. During all of that time he had the good fortune to serve under the leadership of Dr. D. W. Abercrombie, a teacher and leader of rare capacity and power who left upon him a deep and abiding impress. His varied duties in Greek, English, German, and history and in the maintenance of the strict discipline which characterized Worcester Academy undoubtedly helped to develop in him many of the strong qualities which distinguished his later work at Dartmouth. During the last two or three years of his service at Worcester Academy his interest in history grew rapidly and became henceforth his main interest.

In 1891 he was appointed Morgan Fellow in history at Harvard University, where he studied for two years in the graduate school. Toward the end of that period he was appointed professor of history at Dartmouth with a year's leave of absence for study and travel abroad. The time was spent in study in England and in Germany and in travel in Italy, Greece, and Egypt. While at Florence he first met Miss Lillian Darlington Smith, of Liverpool, to whom he was afterwards married in 1897.

Returning to Dartmouth in the fall of 1894 Professor Foster confronted a situation which was at once a challenge, and an opportunity. The new day at Dartmouth which was ushered in at the coming of President Tucker had just begun. Although three or four other men, including John Wheelock, had borne the title professor of history and at other times there had been occasional classes in history taught by men whose major interest lay in some other field, there had never been any teaching of history according to the concept and by the methods which Professor Foster was prepared to use and for which he felt a burning enthusiasm. At Dartmouth, too, as at practically all the American colleges of the day, while there was excellent teaching in many classrooms, there was also prevalent a strong tendency to accept as a necessary evil much loose and slipshod work. To many students a new professor who insisted on getting from everybody close, careful, and accurate work, involving the expenditure of much time at the college library, was a dangerous innovator. As a teacher of history, new style, Professor Foster had before him the work of a pioneer.

In consequence, his early years as professor at Dartmouth were filled with hard work, often carried on under trying circumstances. Probably the most disagreeable of his experiences was the one often referred to and remembered by many Dartmouth men because it served to bring to an end a practice from which many and perhaps all of Dartmouth's most revered teachers had at some time suffered. This was the practice of "horning." The quiet, reserved, and dignified way in which Professor Foster acted on the occasion when he was the unlucky victim of that practice contributed in large degree to the success of the measures which President Tucker then took to put a stop to all further outburst of that sort. Within a short time after the affair many of the men who had thoughtlessly taken a part in the trouble came to be among Professor Foster's most appreciative friends.

The rapid growth of Dartmouth in size, which set in soon after Professor Foster began his work, laid upon him some difficult tasks of administration and organization. His success in picking colleagues as his department developed was noteworthy. Several of the men he brought to Dartmouth did their first teaching under his direction. Almost without exception they proved successful and quite a number of them have won notable success. Becker, Boyd, Abbott, and Fay, to mention only a few examples taken from among those who after serving Dartmouth for a time afterwards went elsewhere, have shown his sagacity in picking men of ability. His talent for organization of teaching and for enlisting the effective co-operation of his colleagues was particularly marked in the handling of the introductory course, History One. From some knowledge of how that difficult problem has been handled in a considerable number of colleges and universities I feel warranted in saying that in few places, if in any, was the problem worked out as well and as early as at Dartmouth. Although no attempt was ever made to push the use of the syllabus which he prepared in collaboration with Professor Fay, it exerted a large influence in shaping similar courses at other institutions. In every year Professor Foster gave with notable success one or more advanced courses. But History One was always his chief teaching interest. He took pride and satisfaction in giving his best to that course. I do not know of any other college or university where the senior member of the department for so long a period gave his strength so largely to the introductory course.

For about twenty-five years Professor Foster served as Head of the History Department. Then about nine years ago a general reorganization took place within the College. President Hopkins and the trustees, with the cordial approval of the faculty, having decided that the time had come when permanent heads of departments should be replaced by chairmen and that in the larger departments the office should be filled in rotation, Professor Foster served as chairman for two periods of two years each and then in accordance with the new custom gave place to a colleague who served for a similar period and was then succeeded by another. This change of method did not, however, involve any pronounced alteration in actual practice in the History Department. As head Professor Foster had always consulted his colleagues both individually and collectively as regards everything of any importance and all decisions of consequence had been reached by concensus of opinion after full discussion in department meeting. Whether he served as head, chairman, or simply as a member his role as leading influence was always freely recognized by his colleagues.

Professor Foster always believed and acted on the principle that the first duty of a college professor is to teach. But he was equally convinced that college professors ought also to do research. He felt a serious obligation to do everything in his power to extend the domain of knowledge. In the discharge of that duty he early entered upon a field of investigation which he pursued unremittingly and in which he achieved recognition both in the United States and abroad as a leading authority. This was in the history of Calvinism. His high standing as an authority in that field brought him in 1909 the honor of a Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Geneva.

Prof essor Foster was deeply interested in Calvinism as a theological system, recognizing in it a mighty force which had shaped the religious and moral natures of millions of men and women in many lands during a period of nearly four hundred years. He was, perhaps, even more interested in the political and social influences which Calvinistic thinking had exerted in the modern world. To a degree that was given to but few men he grasped the significance of the ideas of Calvin and his followers in matters of government, education, trade, and industry. He was especially interested in tracing the manner in which the ideas that John Calvin had proclaimed were modified, diffused, and applied by his followers in many lands, many of whom did not themselves fully realize the source from which their ideas were derived. In pursuit of knowledge on that subject he made many journeys to Europe, spending long periods of hard study at Geneva, London, and Paris and shorter periods in various regions where Calvinistic influence had at any time been particularly strong. No amount of trouble and no expenditure of time seemed too great if thereby he could add something to his knowledge of his subject. Some of the results of his painstaking study were published from time to time in articles which appeared in the American Historical Review, the Hibbert Journal, the Harvard Journal of Theology, and in other learned journals. It was well known to his intimate friends and to specialists in his field of study that he was at work upon a large book which would bring together the results of his work. It was to have been called The Puritan State. But the scope of it was to have been wider than the title might indicate, for his theme was the diffusion of Calvinistic political and social ideas. He had hoped and expected during the sabbatical year on which he had entered to complete the research and to get the writing well along toward completion. At present nothing certain is known as to the precise status in which he left his work. It is to be feared, however, that the tremendous difficulty of the subject and the scarcity of qualified specialists in that field may result in the loss of the most valuable portions of his labor. If so, the loss to scholarship will be heavy indeed.

As an investigator Professor Foster did not confine himself exclusively to the history of Calvinism. His intense interest in everything connected with Dartmouth led him into extended investigation into the history of the College and the lives of some of its famous graduates. He was particularly interested in Daniel Webster and Rufus Choate. His studies upon Webster showed conclusively that widely accepted ideas about Webster's indolence as a student and excessive drinking rest upon nothing more substantial than idle gossip and hostile assertions by political opponents and that the really pertinent evidence points to the conclusion that Webster was diligent as a student and did not indulge in liquor beyond what was customary in his day. One of Professor Foster's studies upon Webster attracted a great deal of attention. It was upon Webster's much discussed Seventh of March Speech. Professor Foster brought together an imposing array of evidence to show that, contrary to the assertions of Webster's critics, the Union was in serious danger of disruption and apparently could be saved only by compromise. Webster's course in supporting the Compromise of 1850, which he advocated in that speech, Frofessor Foster argued with great cogency, should be attributed to his love for the Union, rather than to presidential aspirations and indifference to slavery, as his political opponents charged.

The very active life which Professor Foster led as teacher and historical investigator did not consume all of his attention. In his church and in the life of the community he was always active. By inheritance and by conviction he found a place to fill in the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College and had at all times a leading part in its activities. In town and village affairs he was always deeply interested, attested among other things by the editorial work he bestowed upon the publication of the Hanover town records.

He was for many years the secretary and most active official of the Stockbridge Club, an organization for the boys of FTanover. The splendid work of that useful institution was largely due to his interest in it. It was in another form of what his intimate friends knew to be one of his most characteristic traits, a deep love of children. At Christmas as Santa Claus at the Sunday School celebration and as the. leader of the children's chorus which sang carols under the windows of the sick and those confined to their homes he helped to bring joy into many lives, both young and old.

His activity over a long period as class secretary was a labor of love which brought him rich returns in the appreciation of his classmates and was evidenced by the remarkable way in which they responded to all appeals in behalf of the College. To an extent which was rare even among the most devoted sons of Dartmouth he gave himself without stint to the service of the College. A few days before his death he wrote in one of his last letters a few words which fittingly sum up his life: "I have to make an effort not to think too much of College and Department work."

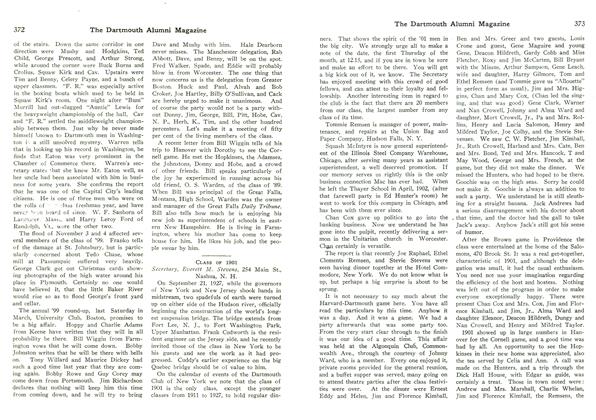

Herbert Darling Foster '85

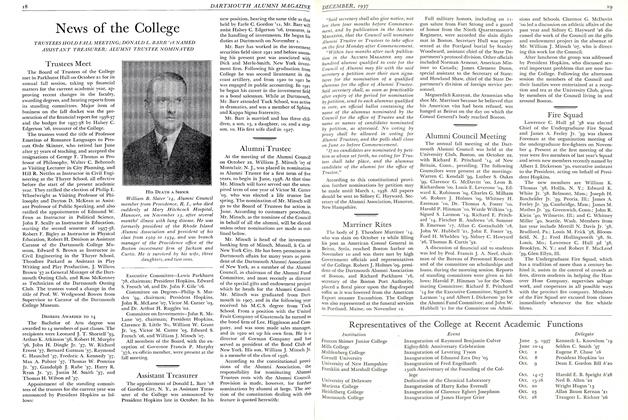

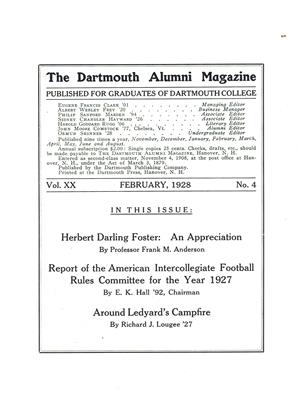

A view of Prof. Foster's last class in Reformation History taken in May 1927 Photograph by R. J. Lougee '27

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsREPORT OF THE AMERICAN INTERCOLLEGIATE FOOTBALL RULES COMMITTEE FOR THE YEAR 1927

February 1928 By E. K. Hall '92 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1928 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

February 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1901

February 1928 By Everett M. Stevens