The Sorbonne at Paris began manufacturing graduates in Theology, Letters, Philosophy and kindred subjects, several centuries before Columbus sailed to find a place in which the world might be made safe for Democracy. Consequently, its output in Masters, Licencies, Agreges, Doctors in this and that, Professors and the other variously named autocrats of the intellectual life, has been enormous.

Likewise situated in the Latin Quarter, or near, are, or were, countless colleges or lycees, markets for the lowly Bachelor's degree. Of an endless list are the College de Montaigu, College de Fortet, des Gravins, des Ecossais, de Reims, Louis le Grand, des Chollets, de Plessis, de Coqueret, de Thou, de Presles, des Lombards, de Karembert, de la Merci, de Ste-Barbe—these names to be recited only as a prologue to the colorful educational drama that has been unrolling in the Latin Quarter for a thousand years.

The various schools of Art, Medicine, Theology, Science, Pharmacy—not to speak of the nearby Halle aux Vins and the numerous brasseries have also turned out their tens of thousands of youths equipped for the struggle of life. On the Hill Ste-Genevieve the turbulent Law School has done through the years what it could to teach the budding lawyer the most dignified method of dropping the Apple of Discord among prospective litigants.

In isolated grandeur to one side, the College de France has long catered to the more rarefied spirits and minds. It is, perhaps, the only real—at any rate, the greatest—"institution of higher learning" in the world. Its teaching and research cover the entire field of human thought. It is this or similar universality of knowledge that caused Anatole France to write in his best Voltairian manner, in his "Monsieur Bergeret in Paris," the advice to a father to have his son given the best possible instruction in language:

"There is also a certain Polynesian dialect which was spoken at the beginning of the present century only by an old colored woman. When this woman died she left a parrot. A German scholar managed to collect a few words of this dialect from the beak of the parrot. He made a lexicon out of them. It may be that this lexicon is taught at the School of Oriental Languages. I strongly advise your son to inquire into the matter."

One would like to catalogue here all those dead great who had their early training in the schools of the Latin Quarter the old Quarter. In the United States, we are apt to associate with a few of the seven-hundred-odd colleges and universities that are spread over three million square miles of territory, a single name or two, here and there: Alexander Hamilton at Columbia; Daniel Webster at Dartmouth; Thomas Jefferson at William and Mary; John Adams and Emerson at Harvard; Jonathan Edwards at Yale; Hawthorne and Longfellow at Bowdoin; Poe, a year at the University of Virginia, and so on.

Names like those of Lincoln, Washington and Franklin are found in no college roster, though they were, perhaps, almost the only ones capable of sustaining comparison with the greatest of their European contemporaries. But the life history of the various schools of the Latin Quarter reveals on every page the names of such as Erasmus, Voltaire, Moliere, Loyola, d'Alembert, Villon, Bossuet, Turgot, Calvin, Balzac, Guizot, Ronsard, Pasteur, Racine, Richelieu, La Fontaine, Berthelot, Chenier, Boileau, to mention only a few names whose primacy is beyond dispute.

It has been asserted that chance plays the major role in the geographical distribution of great intellects. Milton and Rousseau barely missed becoming American Colonists. Would they have written their masterpieces in that case? Albert Gallatin, a noted figure in our annals, was first a Swiss. Thomas Paine, a Britisher, is one of the shining names in American history, yet France claimed him almost simultaneously as citizen and legislator. Whitman, perhaps the most typical of American poets, is best understood in France; as Thomas Hardy,

the Englishman, is best appreciated in the United States. Conrad, the Slav, with perfect command of the English and French tongues, being forced to choose, became an "English" author.

Whatever the cause, one would scarcely try to balance the names of Michael Wigglesworth and Racine in the seventeenth century; or compare Cotton Mather to Rousseau, or Jonathan Edwards to Voltaire, for genius in the eighteenth; or make comparisons of equality between Hawthorne and Balzac, or Longfellow and Musset, or Hugo and Bryant, in the, nineteenth.

Whatever comparisons may be made, and whatever be the yard-stick used to measure, probably no other part of the world of like size—except ancient Athens ever saw an aggregation of worlddominating intellects equal to that trained in the Latin Quarter.

With the Latin Quarter now embracing several more square miles of territory than a century, or even a quartercentury ago; with some of the ancient landmarks effaced—the things that made the Quarter sui generis are rapidly disappearing. Most features of the old student life are now gone forever. Oh, yes! Sightseeing busses drive up and down those empty aisles of long ago, and the modern tourist is told most interesting things, just as he is told things in the departed Greenwich Village and Chinatown of New York.

Americans and Swedes and Slovaks and Germans and Englishmen, on the still-hunt for the exotic, come face to face at dark corners of old-world streets, slip furtive glances at each other and depart thence, quite satisfied that messieurs les Apaches are still being turned out in 'sufficient quantity for the thrillconsumers of the world. They are—but rather in the Montmartre quarter—and then mostly for the tourist trade.

The Rotonde, a cafe much favored by Scandinavians and Russians, is now, for practical purposes at least, included in the Latin Quarter. Here Lenin and Trotzky played countless games of chess, while they concerted moves to put into operation Luke I, verses 52 and 53, taking care that the rest of the Bible should be nationally discredited.

Almost across the street is the Cafe de Dome, hangout for a few Frenchmen, grisettes who have heard of a country with million dollar gate receipts, and daily droves of American tourists. An occasional sprinkling of successful American writers, and a deluge of less successful ones, keep up the fiction of "atmosphere." Radical? Yes, sir-ee! A place where both "bocks" and thrills are on tap.

The Boulevard St. Michel—the French students' own familiar abbreviation, "Boul' Mich,' " now comes tripping off the lips of millions of fair flappers, who have made a two-hour stop there, in a summer marathon from Kalamazoo to Kamchatka and back for life—the Boul Mich' was once the artery of a gay student life, before the coming of the foreign devils. Today, with its chain store of "One Hundred Thousand Shirts," "Chaussures Raoul," "Chaussures Fitizy," and tiny tea-rooms in place of the old brasseries, it is merely another "Main Street" added to the world's oversupply. Valhalla turned into shoe-shine parlors! Imagine a Place of Romance where mead is supplanted by "five o'clocks," and sword and dirk by American baseball bats.

As Cook's and third-cabin tourist peerades began to approach their zenith, the Latin Quarter started a rapid drop to its nadir. The life there has lost something of its zest: the beer tastes different; the wine no longer sparkles. Even those old friends, Camembert and Brie, noisome but tasty, and good for a daily kick when approaching old-age virtuosity, have lost their seductive whiff.

Something over a quarter-century ago the writer started his periodic pilgrimages to the shrines of learning in the Latin Quarter. The tide of foreign students was setting at the time in the direction of the German universities. Comparatively few American graduate students were to be found about the, Sorbonne, the Ecole des Hautes Etudes, or the College de France. The "special courses for foreigners," that today draw hordes of young American undergraduates and are distinct from the stiff program of the French students, are a recent development.

At the time I speak of, the few American students lived as the French students lived, mingling freely with them, taking the "closed" courses under famous savants, when admitted as qualified; in a word, sharing the ordinary life of the Quarter.

A summer ago I dropped in to visit the room I once occupied in a little "hotel" just across from the Sorbonne. At first sight it seemed that nothing had changed. It was a luxurious room for a student of the old days. A famous university was paying my way: I had nine hundred dollars to pay my passage, to keep me eighteen months in France, and to provide me with the, means to live the riotous life. From the point of view of the average French student I was next thing to a millionaire.

Eight by ten, with a tiny fireplace as sole heat-giver, my room boasted a window looking on the narrow street. There was no bathroom, to be sure, but that lack could be remedied from a cracked pitcher, if the winter's day were, not too cold for ablutions, or if a handful of coal remained of a morning to raise the temperature a dozen degrees. Otherwise one reverted to the old custom of Saturday night back on the farm, or one went to the public bath—occasionally.

After all, the question might be raised, as it was by one. of the characters in Du Maurier's "Trilby," whether too much emphasis has not been placed upon the employment of water for purely hygienic purposes, not to speak of hm internal uses. Middle-aged of a famous New England college still speak affectionately of the winter days when they had to rush from their dormitories to make an eight o'clock toilette at an ice-bound pump in the yard, with the temperature thirty below zero. In my own case, my experience caused me for many years to have profound sympathy for the Eskimo, and to excell the camel in my aversion to hydropathy.

The furniture remained the same as twenty-five years ago, though the hotel had changed hands a dozen times. The same worn rug, dirtier and more frayed, took up four square feet of floor. The same eiderdown upper mattress; the same sinister bloodstains on the wall near the bed, telling of human victory in furious night battles with the jungle life of a boarding-house. Everything was the same,. No, there was a change. The new proprietor spoke proudly of a "douche" or shower-bath that he had lately installed, in addition to the bathtub of the preceding year. I shivered at the thought, until I learned that "central heating" now took the place of some thirty fireplaces.

My cup of bitterness ran over. Knowing what poor French students had to put up with then as now, I had considered myself most fortunate in my luxurious quarters with all their discomforts. I had kept tucked away in a corner of my memory an idealized picture of the Quarter as a symbol of the eternal struggle of mind hunger against stomach hunger. Was the Latin Quarter now on the way to "innocuous desuetude" due, like the decay of ancient Greece and Rome, to too many softening influences, to the enervating effects of machine progress? Can genius thrive in hot-house atmosphere, without the spur of suffering and hard knocks, the sting of poverty?

A recent article on American education has stated that French students of collegiate and graduate rank are for the most part recruited from the upper and wealthier classes, whereas the majority of American college youth come from the poorer homes. You may have formed your own conclusions as to the second part of this assertion. Certainly, the most striking thing about the first clause is its utter erroneousness, both as to fact and deduction. No one in position to judge can have failed to remark that the French student has, eight times out of ten, been a product of the survival of the intellectually fit; of the struggle, between inadequate financial means and eagerness for mental development.

What I have tried to express concerning the French tribute to intellect and learning developed under stress, is reflected in a passage from an amusing little book, written just a hundred years ago, "The American in Paris," by John Sanderson, a Philadelphian:

"One of the eminent merits of the French character is the distinction they bestow upon letters. A literary reputation is at once a passport to the first respect in private life, and to the first honors in the state. . . It is not that Paris loves money less than other cities, but she loves learning more, and that titled rank being curtailed of its natural influence, learning has taken the advance, and now travels on the high-way to distinction and preferment, without a patron and without a rival. At the side of him, whose blood has circulated through fifty generations, or has stood in the van of as many battles, is the author of a French History, born without a father or mother. Who is Guizot, and who Villemain, Cousin, Collard, Arago, Lamartine, that they should be set up at the head of one of the first nations of Europe,? Newspaper editors, schoolmasters, astronomers and poets, who have thrust the purpled nobles and time-honored patricians from the market of public honors. . . Poverty was their birthright, and their learning in every case, implied a fight to acquire education under adverse conditions."

If the housing conditions of the many poor students of the University has been for ages below a proper level of comfort and hygiene, the question of sufficient and nourishing food has been an equally distressing problem.

A century ago, this same John Sanderson was able to buy a filling meal for the equivalent of twenty cents, consisting of soup, vegetables, fish, meat, bread, and a small bottle of ordinary wine. As French cooking had been celebrated for centuries before his time, and as calories and vitamins like radio, the auto, and the 18th Amendment, were still in the dim future, it may be assumed that the meal was nourishing. Even such a price was often a tax upon many a student's purse.

Twenty-five years ago, according to my own account-book, I paid the equivalent of twenty-five and twenty-seven cents for lunch and dinner, respectively. This included the proper tip of two cents. The items on the menu to be had for this sum were practically the same, as those mentioned by Sanderson. A summer ago I strolled into the same restaurant of my student days, ordered the same dishe.s, and paid something over six francs, about twenty-six cents, with tip. But it must be remembered that the franc was worth only four cents American at that time, instead of the pre-war value of over nineteen cents. For me the price of a meal had remained stationary over a period of twenty-five years.

For the French student the cost of a nourishing meal at a miminum price had tripled, allowing that wages and salaries had doubled since the war; hence, that their students' income had likewise doubled.

I watched dozens of these young men order meals, remarking the care with which they put aside the fixed price dinner menu and chose one or two substantial dishes: soissons (white beans) and an abundance, of bread, with a tiny carafe of inferior wine. In the absence of any statistics on the subject, I will refrain from any exaggerated and misleading statement. My observation and my conversations with those in position to know the whole facts warrant my saying that there are many, too many, University students of the Latin Quarter who suffer from under-nourishment and bad housing

conditions. Those in high authority recognize this fact and are seeking to remedy it. Tens of thousands of the most promising young intellects of France were sacrificed to the World War. The seventeen Universities of France are state-controlled and state supported. It thus becomes the duty of the State to see that the old traditions of brilliant intellect and profound learning are continued. This can be done only if the health and brain efficiency of the new generations of University students are guaranteed against discouraging economic conditions.

It is apparent that the Latin Quarter and its student life are at the parting of the ways. As I have tried to show, the Quarter has lost much of its old color and individuality, for one cause or another. Is the University student to be driven in upon himself to maintain what he can of the old traditions; to save a remnant of the colorful life of olden days by burrowing still deeper into more musty and squalid surroundings, at the expanse of health and efficiency? Or while retaining his, age- old intellectual habits and aspirations—is he to yield to a new economic system that will safeguard his health while stripping him, it may be,, of part of his individuality ?

The fact is, a remarkable experiment is being tried, and is meeting with great success, in connection with the student life of the, University of Paris. It has passed almost without notice in the United States. To the average American, accustomed as he is to the paternalistic features of our colleges, it will have little significance, unless it be studied in connection with what I have tried to picture briefly in the first part of this article. Time will show it to be revolutionary where the French city student is concerned.

Twenty minutes distant from the Latin Quarter by several lines of trams and auto-busses, is the Montsouris Park, one of the most delightful spots in Paris. Running parallel to the edge of the park are the remains of the old southern fortifications of Paris. Above these earthen ramparts, the CITE UNIVERSITAIRE is in course of construction, where criminal outcasts, low hovels and a wild tangle of thickets made a Sunday or evening stroll a dangerous pleasure a decade or so ago.

Last summer, at the kind invitation of the educational authorities, II made my home, at the Cite Universitaire for several months, long enough to realize how completely the life of the University student is to be revolutionized in the course of the, next ten years. In 1900, eleven thousand students—eleven hundred of them foreign—were registered at the University of Paris. Today, more than twenty-two thousand—including over three thousand strangers from every land —are on the rolls of the University.

The problems which I have stated have been aggravated by the increase in numbers. In the words of the authorities themselves:

"A question arises: how do these young people live through the material difficulties of the present hour? They live badly; if you except a few, scions of the upper middle class, our students come from poor or impoverished families. Many of them, in order to provide for the mere necessaries of life, are forced to menial tasks to provide the few hundred francs that their parents, at grips with poverty, are no longer able to send them each month.

"Nevertheless, there are perhaps those among them whose names, in fifty years, will be as glorious as that of Pasteur, of Berthelot, or of Renan."

In 1920, a noted philanthropist, one of the rich men of France, Monsieur Emile Deutsch de, la Meurthe, had a happy inspiration. He suggested to his friend, Monsieur Appell, Rector of the University of Paris, a plan for aiding a few hundreds of the struggling students of the University. With the suggestion went the sum of ten million francs to found a little "garden city" outside the congested Latin Quarter.

Fifteen months after the offer was made, and while formal plans were being drawn, a law was passed by which the State bought from the city of Paris seventy acres of land lying on and near the fortifications of the Montsouris district. The Government further engaged itse,lf to turn this land over to the University free of cost, that buildings might be constructed there to "lodge students in the best conditions of material and moral life." A further provision was in contemplation of certain uses of thesegrounds for games and sports.

Before these plans could go into effect, Monsieur Andre Honnorat, at that time Minister of Public Instruction, conceived the idea of enlarging the scheme. Instead of a "garden city" for three hundred fifty students, he would have a "Cite Universitaire," consisting of a large group of buildings capable of housing over three thousand students, mixed as to nationality, but each nationality having a house of its own. These houses were to be constructed on the plan of American college dormitories. The general scheme, however, was in consonance with the international character of the University of Paris in the Middle Ages.

The Cite Universitaire, then, represents both a forward step in the amelioration of student conditions of living, and a backward glance at time-honored traditions. To be sure there will no longer be, as in the Middle Ages, groupings of students and masters into "Nations "Nation of Normandy" (comprising the Normands and Bretons) ; "Nation of Picardy" (Picards and Walloons) ; "Nation of England" (English, Germans and Swedes) ; "Nation of France" (that included all those students of Latin race.)

Instead, the Cite Universitaire will, when completed, give, to the world, through the medium of Education, the most amazing picture in history of international comity. Were future statesmen and diplomats brought together to live for a year or two in intimate contact, while pursuing their graduate studies in this greatest of all centers of learning the University of Paris—it is not inconceivable that the modus vivendi in the Cite Universitaire would have far-reaching effects upon that in international affairs.

The French section of the Cite Universitaire consists already of eight fine buildings, including dormitories (each named after some celebrated Frenchman,) restaurant, administration buildings, general hall for club purposes, dancing and the like, and attendants' quarters. There is abundant steam heat in all the buildings, running hot water that is really hot, bathtubs and showerbaths of the best design, and toilets that make one's recollections of old days in the Latin Quarter seem like nightmares.

The restaurant is run on the cafeteria plan. After my experiment in the, Latin Quarter, with respect to minimum food prices for the student, I tried the restaurant of the Cite Universitaire. I became an habitue of the place, as far as my duties elsewhere would permit. The food was excellent and plentiful. I could satisfy a reasonable hunger at the cost of three francs (twelve cents), and I found that the customary pourboire was not only not accepted, but actually forbidden by the administration. A student, who was neither a gourmand nor a gourmet, could conceivably be properly nourished at an outlay of even less than six francs a day (twenty-five cents).

The students' rooms are, comfortable and well lighted, comparing favorably with most American dormitory rooms. The price per month was set by a benevolent administration at a sum that would not have paid for the most squalid "hotel" room in the, Latin Quarter. From his windows, the student can see grass and sky and trees. Many windows have a vista across Montsouris Park, or into the countryside. The noise of trams, and the tooting of automobile horns that makes sleep often impossible in the heart of Paris, come to the Cite Universitaire only faintly.

Upon the completion of the first buildings, the French Government found its funds too depleted and its other financial obligations too heavy, to carry out the rest of the building scheme at that time. But a rumor of the undertaking had spread to other countries. Monsieur and Madame Biermans-Lapotre of Belgium, being "friends of France and French culture, " made a donation of five million francs to the University of Paris to be used to construct a Belgian House, for two hundred Belgian students. Land was given them by the Government and the house was opened in 1926.

Since then a Canadian House has been built and occupied. In course of construction are houses for students of the Argentine Republic and of Japan, built with money donated by those countries. The foundation stone, for the British building was laid last July by the Prince of Wales. These three buildings will be ready for occupancy before long.

Sometime in the near future, it is expected, work will begin on an American Dormitory to house more than two hundred and fifty students. The building will cost in the neighborhood of four hundred thousand dollars, of which a trifle more than one-third has already been donated. While committees have been working in both the United States and Paris, progress has been unexpectedly slow. Curiously enough the entire scheme, as I view it, is a reflection of the American dormitory system, expanded to provide for all the nations of the universe. Moreover, one of the finest plots of land was assigned to the Americans.

For many years past French rugby teams have had their fair share of victories in international contests. French tennis has lately taken the first rank, after a phenomenal rise. Track games are here and there producing "stars," although the development in that sport has been very recent. Baseball is gaining in favor. But at present most of these sports have their center in some Union Sportive. They have touched the lives of the students only incidentally.

All this is likely to be changed. The Cite Universitaire provides for rugby and football fields, for plenty of tennis courts, for an open air piscine, or swimming pool, and for a baseball field. (In the course of time a track will be added. It is quite certain that in the comparatively near future the old fortifications will resound to the shouts and plaudits of an international bleachers crowd, when an American, Sullivan or Lodge, "poles out a homer;" or a double play—Mus- set to Poincare to Renan—will decide the Cite Universitaire series.

The sight of American college athletes, scarcely disguised by the vain trappings of civilization, and trotting along through our crowded city streets, no longer excites the comment of the man who walks. In the Latin Quarter, where the appearance of the harem of the Maha- rajah of Semaphore, or the eccentricities of some Sultan of Oz, provokes only a lazy yawn, such scantily clad runner would, a few years ago, have excited more than passing attention, if not ribald interest. With the development of an athletic field at the Cite Universitaire, one may confidently predict a change of attitude.

Athletic sports received their greatest impulse in modem times in Anglo-Saxon countries and reached their present greatest development, to the conceded point of over-emphasis, in the United States. The acknowledged benefits to American youth of properly supervised physical training, as well as the dangers of its exaggeration, will continue to be the subject of comment in academic circles and in public print. The debates on this subject have been followed closely by foreign educational authorities. In a discussion of the matter that the writer had with one of the most famous French scholars, a member of the French Academy, in 1924, the Academician stated his firm belief in the good that would arise from the introduction of more athletics among University students. His attitude seemed to be, not merely personal, but a reflection of the opinion of brilliant colleagues.

The whole matter of the Cite Universitaire, then, is as I have said, a definite step in the process of the disintegration of the Latin Quarter. It involves the disappearance of the last vestiges of the colorful life that has made the Quarter the theme of countless books and poems for centuries past. But that color had largely disappeared, anyhow, as a result of several influences.

There are, of course, vastly sentimental reasons that make many Frenchmen, as well as many foreigners, loath to concede the validity of a Modernism that would drive the Quarter out of existence. The fact remains, however, and these same Frenchmen, with their usual clarity of perception, concede the fact. In fact, the premonition came to some, as early as the middle of the past century, that the Quarter was doomed:

"Alas! It's all up with us ! French youth Is dead with the old Latin Quarter." Of yesterday is the plaint of still another writer:

"Its artistic cabarets, its legendary cafes, its memories of yore—all is in dissolution. What remains of this old Latin Quarter, where one found such gay amusement but a few short years ago, where joy hovered lovingly over this center of intellectual life, and over the thinking heart of the youth of our Schools?"

The Cite Universitaire is due to supplant this life. In return, it will give guarantees of health and comfort to thousands of students who are the hope of future France. A mere layman, I indulge the belief that the Cite Universitaire will become the foyer of lasting international contacts for brilliant youths; contacts leading not necessarily to "internationalism," but to sympathetic understanding in middle and old age of the nations' leaders and thinkers.

Despite the call of Progress and Modernism, each man of middle-age must retain, on some pet subject, a sneaking bit of the retardataire within him. I confess freely to a lingering sentimentality about the Latin Quarter. I have wondered how Master Frangois Villon would feel. And Boileau, the champion of the Ancients.

One of the Dormitories

Exterior view of the French buildings

The University Restaurant

Professor of French

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

May 1928 -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH HALL IN CHINA

May 1928 By Harold W. Robinson '10 -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

May 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1922

May 1928 By Francis H. Horan

Article

-

Article

ArticleSnow Train

March 1935 -

Article

ArticleUnder-standing Polymers

APRIL 1994 -

Article

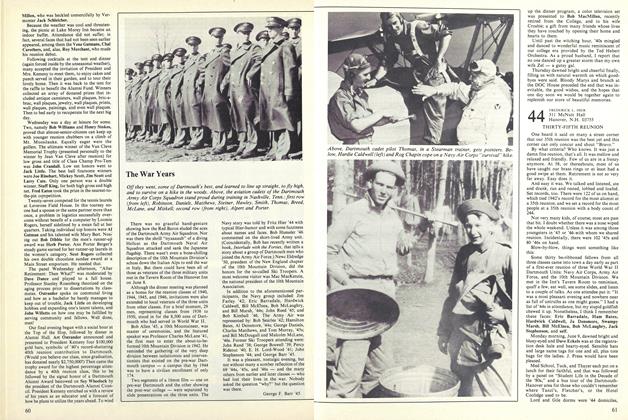

ArticleThe War Years

September 1980 By George F. Barr '45 -

Article

ArticleFrom a 1908 Mem Book

February 1935 By L. W. G. -

Article

ArticleEMPLOYMENT FOR ALUMNI

December 1943 By PROF. FRANCIS J. NEEF -

Article

ArticleSeattle

MARCH 1968 By STURGES DORRANCE '63