Dartmouth's Opportunity

An anonymous contributor has sent in the communication which we feature on the page immediately following the editorial section. It has seemed to the editors so important in its thought and so ably and forcibly expressed that we have wished to bring it before the readers of the MAGAZINE in as conspicuous a way as possible.

There is no means of telling when, if ever again, Dartmouth may be faced with such an opportunity as the present, with a president at its head, who has the vision to see and the capacity to carry out, if only the material resources are available. But the element of time is inexorable and the present happy combination of circumstances must of necessity be comparatively brief.

This exposition of our present but limited opportunity should be carefully studied and pondered.

Edwin W. Sanborn

Edwin W. Sanborn represented a Dartmouth known to most of us only by tradition but a tradition that is extraordinarily vital—the Dartmouth of the seventies and the Campus surrounded by the white colonial homes of the faculty. One of these homes was occupied by Professor E. D. Sanborn, affectionately known as "Bully," and beloved by generations of students for over forty years. The home held such an atmosphere of literary culture and genial friendliness that it seemed to supplement and complete the hours in the classroom. In it grew up Kate Sanborn, one of the notable figures of American literature, and the late Edwin W. Sanborn, whose benefactions to the College have been announced recently.

It is therefore altogether fitting that his gift should take the form of a continuation of the work of his father in the College. The English House which Mr. Sanborn's munificent gift will provide offers the opportunity to continue the tradition of friendly, intimate association between instructor and student that was characteristic of the long professorship of "Bully" Sanborn. There is further generous provision for the annual purchase of books that formed the basis of the strong influence of the Sanborn home of earlier days. The fact that Professor Sanborn was at one time librarian of the College only adds to the felicity of the gift.

Although an invalid for years Edwin W. Sanborn still had the opportunity to impress his own powers of literary expression and appreciation on the changing college. Those who had the good fortune to attend the Webster Centennial in 1901 will recall his delightful paper on Webster's personal life and associations and also occasional later contributions to this MAGAZINE. In one such contribution prepared at the time of the Sesqui-Centennial he states his abiding faith in the College and confidence in its future:

"Upon the globe where our lot does happen to be cast there are some eighteen hundred millions of persons. If I had the pick of the whole flock I would choose for the job of heading the administration of Dartmouth College no other than its present head. I would waste no time in looking for better men than the present board of trustees. I take off my hat to the men who are doing the teaching. They have each and all kept the faith. And it looks to an unbiased observer .of the great conflict between Light and Dark- ness as if this moral continuity were a good thing. The mere fact that a college is old doesn't carry much credit. Anybody can be old if he lives long enough. The trick is to get the cultured discernment of age while keeping the alert adaptability of youth. This College, has the spring of youth and the autumn mellowness of age. It has capitalized its winter and it has the makings of an intellectual capital in summer. It is endowed alike by environment and heredity.

"Dartmouth College keeps those hereditary traits from dying out. It has found the secret of its founders. Those far away folks who put the college on the map were men of serious faith and purpose. They believed that beyond the ceaseless shifting of the things we see and hear and feel are other things that stand like a ledge of New Hampshire shire granite behind the fogs that rise from the river. They made it the business of their lives to find a way through the mists and build their house upon a rock. Why shouldn't Dartmouth College grow as long as grass grows on the campus and water runs in the placid river? Why shouldn't it last as long as snow is white and the hills are dressed in living green?"

Mr. Sanborn has demonstrated his faith by his works and done much to secure the future foundations of this house he loved so much.

The Honor System

Debate has arisen again—this time at Yale—concerning the feasibility of the so-called "honor system" of conducting examinations, the students themselves alleging that there is so much "indifference " as to make it desirable to abandon the practice of that system and revert to faculty supervision. In other words, one may gather, the students feel that there are such serious defects in the method of putting examinees oh their honor that there is warrant for invoking the old-time customs, in which professors, or proctors, always sat in examination rooms and kept a vigilant watch for the detection of cribbers.

It is difficult to avoid the belief that this is destined nearly everywhere to be the final verdict. The resort to illegal means of passing examinations is as ancient as education itself, and will probably continue among imperfect human beings down to the end of time. When the faculty sat in supervision of such events, the students often felt it was a sort of game of give-and-take, in which the student was practically dared to crib if he could. * When the faculty ceased to supervise and when it became a matter of honor with each individual, there were still a few who lacked the honor—and the difficulty then arose that more honorable students, observing the infractions, were expected to become informers—never a popular role. The whole idea of the honor system, however, rests on the postulate that when young men are placed on their honor no one will be so pusillanimous as to offend; not on the idea of universal espionage. In the great majority of cases one suspects the theory to be valid—especially when the system is still new. But it is not universally valid; and as such matters become an old story, there is likely to be an increase in the number of offenders without any corresponding increase in the readiness to bear tales. One by one the users of the honor system have come to question its suitability and to sigh for the good old days.

Examinations are rather poor things at best, but no one has ever devised a very satisfactory substitute. The one known way of discovering how much students have learned is to ask them; and of course the answers are of value only when they are honest answers, unassisted by written memoranda furtively consulted. The practical question concerns the best way to secure honest answers, and it appears to be quite generally felt that the "honor system" fails to insure them to the degree originally expected. Possibly the old idea was best, but it must be admitted that there was abundant cheating even then. The uncomfortable thought is that the appeal to individual honor is written down such a failure among the young themselves, who are the principal accusers of the honor system. It is a disappointment to their elders—more of a disappointment to them than it seems to be to the boys, who quite frankly complain of the general "indifference" of their fellows toward a matter which had been fondly hoped to be of paramount concern to them.

Young Men and Books

A rather interesting experiment, still too young for positive comment, has been made this winter at Hanover in the form of a monthly supplement to the issues of the Daily Dartmouth devoted to literature—in large part to the criticism of new books, though not exclusively. Since literary criticism in the United States is in rather a chaotic condition at best, it would be rash, to hold a publication by men in college to the standards set by such authoritative publications as the Yale Review, or Mr. Canby's Saturday Review of Literature, but the effort to stimulate literary interests among men who will one day be buyers of many books and the makers of domestic libraries should certainly not be amiss. The editors modestly announce that they expect their attempts to be "diverting and amusing," but one suspects that among the intentions is to be provocative as well—after the current fashion.

What chiefly interests, however, is a chance article on the books which college students appear most eager to buy at the local emporium devoted to the sale of literature. One is told that the sales fall into two main classes—one, the newest books about which current readers are talking the most; and the other, standard works, "mentioned or recommended, but in no sense required by the faculty." The best-sellers of the moment one may take for granted—and probably in most cases ignore, as bearing but little on the tastes which these younger men are forming. It is more surprising to note that "books in fine bindings are in great demand," because the purchase of works promising permanency of possession might not have seemed to be a common practice among men at a care-free age, whose households are still matters of the future. It would certainly have been so in the meagre years when few Dartmouth men had the means, even if they had the taste, to begin the accumulation of libraries, and when the chief function of a local bookstore was to purvey the required volumes demanded by actual courses of study. Times have changed, it appears, and the bookstore in a college town is expected to do something toward the encouragement of substantial foundations. More power to it!

The commentator, quoted an experienced observer from the book-seller's viewpoint, expresses a belief that while college students are amenable to suggestion, either from "authorities" or public opinion, they reveal little curiosity about investigating for themselves, or for initiating lines of reading. It is hardly surprising, since much the same thing is true of much older persons and has borne recent fruit in expert committees offering to provide "a book a month" for such as have no disposition, or talent, to manage this activity for themselves. "Only a small percentage," he goes on to say, appreciate the opportunity to begin the assembling of wellrounded libraries for themselves, or avail themselves of a chance which later on they will probably regret having neglected. That, however, seems to us quite inevitable in the circumstances. Concerned with books as a matter of daily task, the student in college is fairly sure to seek other avenues of enjoyment in his hours of ease—precisely as in later life, when his daily tasks lie in other fields, he will seek pleasure for his leisure hours in books.

We are all by way of expecting too much of college youth. The wonder may well be that even the "small percentage" devote a part of their time and money to the foundation of personal libraries, as well as to the buying of ephemeral bestsellers which will speedily lose their value when people cease to talk of them. One recalls the famous advice, often mentioned by that most delightful of Dartmouth professors, the late Charles F. (Clothespin) Richardson, in the conduct of his courses, not to read any book until it be a year old. One who followed it would miss a little—and spare himself and his pocket a great deal, no doubt.

Incidental items in the article are of interest. The volume of sales of standard poetry, which three years ago was about 15 percent of the business, is reported as having dwindled of late to about 10 percent. In this one suspects the college world fairly parallels the experience of the world outside. The zeal for collecting "first printings" apparently of contemporary books rather than ancient first editions is presumably to a large degree a fad. If only one knew for certain what is going to be immortal! Unfortunately every publisher makes the claim of long endurance for every fresh book he issues, and one has learned to discount rather liberally in consequence. It is an age in which appalling numbers of books are printed and in which a fairly staggering number of books will be talked of sufficiently to inspire a wish to know a little about them in the breast of any one eager to appear abreast of his day.

One notes in passing the wholly-to- be-expected tendency of the college reviewer to lay the most stress on what the publishers' jackets generally call "explosive" books—books urging some novel and delightfully shocking doctrine, preferably dealing with the relations of the sexes, or with some aspect of sociology at variance with anything ever known or tried before. This is the characteristic of one of man's seven ages, and will be outgrown as experience tends to complete the education which colleges merely begin. No wonder that at least three of the four pages of the initial issue of this literary supplement contain references to Judge Lindsey's work on Companionate Marriages!

Increasing Leisure Time

Now and then someone draws up a table of statistics to emphasize changes in the economic situation, such as that with which Mr. Mark Sullivan illuminates one of his chapters in the second volume of "Our Times." In this there is a startling revelation of the strides made since the advent of the Age of Machinery in the way of increasing the productiveness of a day's labor by a single workman in various lines of activity. One knows vaguely that this is one of the facts of current economics, but how clearly does any one visualize the real situation ?

Mr. Sullivan appends to one of his pages on the changes that have come over industry a comparison between the years 1781, when motive power apart from that of animals and rude water mills was unknown, and the year 1925, when steam and electricity had brought mechanical devices to an extraordinarily high state

of 'development. The following is substantially the table as he gives it: A single laborer working one day produced

in 1781 500 lbs. of Iron 100 feet of Lumber 5 lbs. of Nails 1/4 pair of Shoes ton of Coal 20 sq. ft. of Paper

in 1925 5000 lbs. of Iron. 750 feet of Lumber. 500 lbs. of Nails. 10 pairs of Shoes. 4 tons of Coal. 200,000 sq. ft. of Paper.

In other words, the labor of one person today suffices to yield many times what one person's labor yielded 150 years ago—and that means, of course, that less and less time is required to supply the world's daily material needs, even though those needs have been multiplied too. There is a steadily augmenting amount of human leisure to be devoted to other than productive pursuits, and such tables as the above tend to make more vivid a realizing sense of how great that amount of time is coming to be. One result has been the steadyreduction of the length of the working day without leading to improverishment in material production. Another has been the incredible growth of pleasure and the amounts of money capable of being spent for recreation. Most of all, from the educational standpoint, has it resulted in a problem which amounts, especially in the case of an American college, to finding ways and means to teach men, endowed with more leisure than the world's people have ever known before, how to use that leisure with profit and pleasure to themselves and others.

There has been criticism from eminent observers within the past few months based on the theory that the colleges of this country are not training men to be economically efficient; that there is a deplorable lack of instruction in lines leading directly to the production of yet more wealth. There is room for the belief that this is not what the time requires, but that what is needed is precisely the opposite; to wit, training along lines which lead to the helpful use of available periods of idleness.

The Abolitionists

From all over the collegiate map come the rumors of zeal for abolition. The things suggested for eradication are almost unlimited. Fraternites, student government, chapel, required studies, freshman athletics, intercollegiate sportpretty nearly everything has been marked for abandonment by eager young college editors, except the colleges themselves, and (of course) the college press. No budding editorialist has thus far been observed to advocate abolishing himself, although now and then incandescent correspondents protesting against the suggested reforms have hinted that this final deprivation, if it occurred, could be borne.

Perfection is finality, and finality is death. A college with nothing about it which any one wanted to abolish would probably be a very dull and spiritless place indeed. The great trouble seems to be that whatever is abolished usually turns out to make room for other difficulties, sometimes unforseen. The honor system, now inveighed against by student councils and undergraduate editorials, supplanted an examination system under espionage which had evils of its own. There are "outs" connected with nearly everything human. Even the abandonment of chapel requirements seems not to have made everybody happy. However, there is room for doubt that the

attainment of happiness is among our unalienable rights. The most that was claimed for it by the Founding Fathers was an indefeasible right to pursue it. The felicity which we miss when we have attained our hearts' desire must be supplied from the zest of the chase. It's fun, in other words, to be an abolitionist so long as there is something to abolish.

A Photograph of a water color painting by Oliver Wendell Holmes made while a Professor in Dartmouth Medical School. The painting is a gift to the College by William E. Tucker '10.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE CITE UNIVERSTAIRE AND THE LATIN QUARTER

May 1928 By Shirley G. Patterson -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH HALL IN CHINA

May 1928 By Harold W. Robinson '10 -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

May 1928 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1922

May 1928 By Francis H. Horan

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JUNE 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

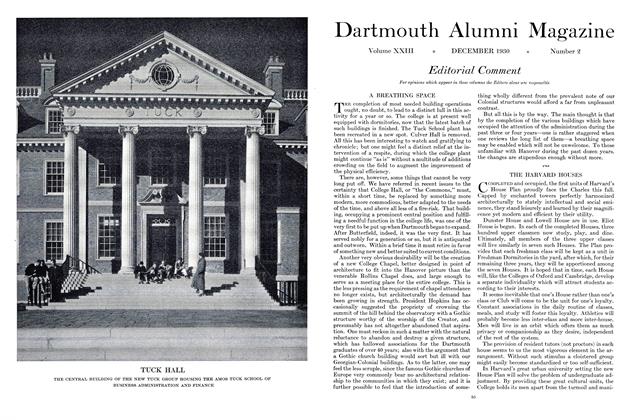

DECEMBER 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

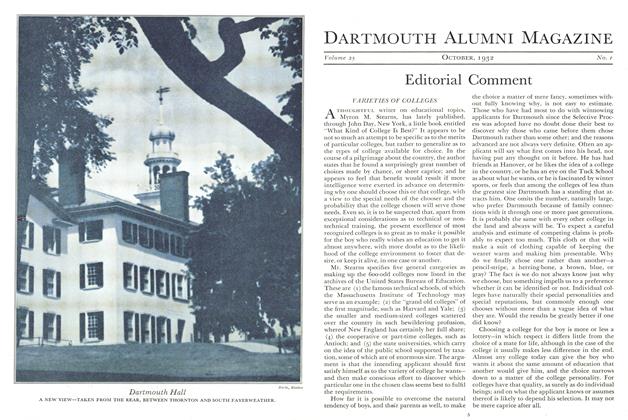

October 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

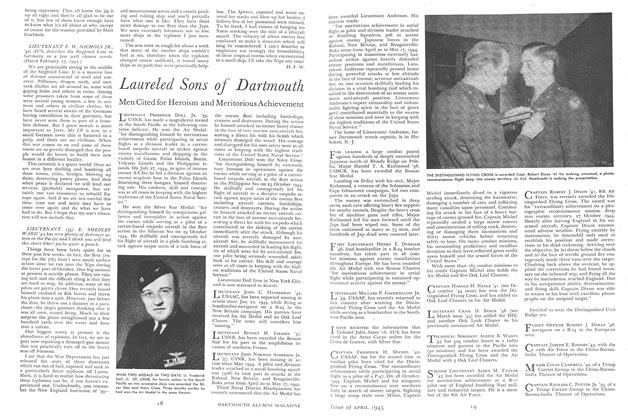

June 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter From Paris

December 1948 By WILLIAM I. ZEITUNG '43