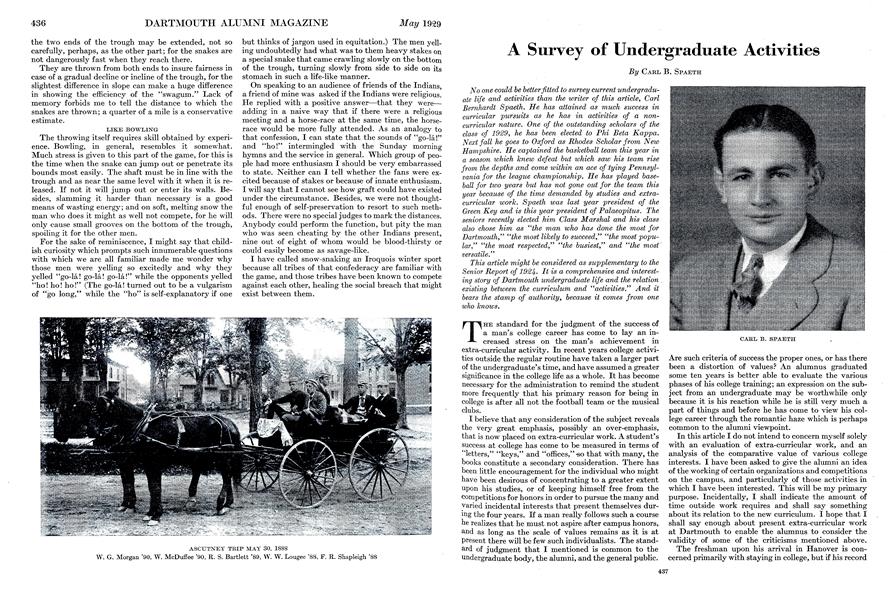

No one could be better fitted to survey current undergraduate life and activities than the writer of this article, CarlBernhardt Spaeth. He has attained as much success incurricular pursuits as he has in activities of a noncurricular nature. One of the outstanding scholars of theclass of 1929, he has been elected to Phi Beta Kappa.Next fall he goes to Oxford as Rhodes Scholar from NewHampshire. He captained the basketball team this year ina season which knew defeat but which saw his team risefrom the depths .and come within an ace of tying Pennsylvania for the league championship. He has played baseball for two years but has not gone out for the team thisyear because of the time demanded by studies and extracurricular work. Spaeth was last year president of theGreen Key and is this year president of Palaeopitus. Theseniors recently elected him Class Marshal and his classalso chose him as "the man who has done the most forDartmouth," "the most likely to succeed," "the most popular," "the most respected," "the busiest," and "the mostversatile."

This article might be considered as supplementary to theSenior Report of 1924. It is a comprehensive and interesting story of Dartmouth undergraduate life and the relationexisting between the curriculum and "activities." And itbears the stamp of authority, because it comes from onewho knows.

THE standard for the judgment of the success of a man's college career has come to lay an increased stress on the man's achievement in extra-curricular activity. In recent years college activities outside the regular routine have taken a larger part of the undergraduate's time, and have assumed a greater significance in the college life as a whole. It has become necessary for the administration to remind the student more frequently that his primary reason for being in college is after all not the football team or the musical clubs.

I believe that any consideration of the subject reveals the very great emphasis, possibly an over-emphasis, that is now placed on extra-curricular work. A student's success at college has come to be measured in terms of "letters," "keys," and "offices,"-so that with many, the books constitute a secondary consideration. There has been little encouragement for the individual who might have been desirous of concentrating to a greater extent upon his studies, or of keeping himself free from the competitions for honors in order to pursue the many and varied incidental interests that present themselves during the four years. If a man really follows such a course he realizes that he must not aspire after campus honors, and as long as the scale of values remains as it is at present there will be few such individualists. The standard of judgment that I mentioned is common to the undergraduate body, the alumni, and the general public. Are such criteria of success the proper ones, or has there been a distortion of values? An alumnus graduated some ten years is better able to evaluate the various phases of his college training; an expression on the subject from an undergraduate may be worthwhile only because it is his reaction while he is still very much a part of things and before he has come to view his college career through the romantic haze which is perhaps common to the alumni viewpoint.

In this article I do not intend to concern myself solely with an evaluation of extra-curricular work, and an analysis of the comparative value of various college interests. I have been asked to give the alumni an idea of the working of certain organizations and competitions on the campus, and particularly of those activities in which I have been interested. This will be my primary purpose. Incidentally, I shall indicate the amount of time outside work requires and shall say something about its relation to the new curriculum. I hope that I shall say enough about present extra-curricular work at Dartmouth to enable the alumnus to consider the validity of some of the criticisms mentioned above.

The freshman upon his arrival in Hanover is concerned primarily with staying in college, but if his record in high school has been one of extra-curricular accomplishment, he has the same ambition for his college career. The selective system by which the men are now chosen brings to the college men who have been captains, class officers, leaders and editors in high school. They arrive at Dartmouth and are immediately awed by the sight of upper-classmen wearing the white hat of Palaeopitus or the green hat of the Green Key. They learn that men may become members of these two honorary organizations by distinctive accomplishment in some extra-curricular work—as manager of an athletic team, as manager of the musical clubs or the players, as one of the directors of the Outing Club or the Christian Association, or as a letter man on one of the teams. Freshmen tend to idolize the campus leaders and naturally aspire to similar positions in the College. If there is "over-emphasis," then, it begins when the firstyear men magnify the significance of campus prestige. As leaders in prep school they found that the popularity and prestige which leadership in extra-curricular work brought them caused their high school careers to be termed "successes"—college is apparently the same kind of game. Many who found high school quite easy are confident that college will be as easily conquered. The attitude is often that of the freshman who" asserted that he was going to play football, hockey and baseball, and that he would devote the rest of his time to the musical clubs—at the end of the year he wasn't out for anything and his chief concern was whether or not the dean would permit him to remain in college.

On what basis do the freshmen make their choice of extra-curricular work? Except for a very few men the main consideration is the amount of campus recognition achievement in a certain activity will bring the individual. At the beginning of the year an "Activities Night" is held for freshmen. At that time seniors who are leaders in their class tell the freshmen of the merits of their particular activities. The short talks by the seniors merely give the mechanics of their competitions, and in some instances a talk by the manager of a certain sport amounts to a salesmanship line given with the purpose of securing the best freshmen for his competition. I am convinced that much more could be accomplished on this night if a concerted attempt was made by the seniors to establish sounder criteria upon which the freshmen might base their selections. The seniors might try to counteract the magnified conception which the freshmen have of the significance of campus popularity, indicating that they might better aim at a goal nearer the ground and at one more practically worthwhile. Their talks could be much more personal, expressing their true attitude towards their work after three years of participation—stating frankly its shortcoming as well as its benefits. Once a man has made his selection, he is to devote a large amount of time to his activity, and it is well for him to be reasonable in his consideration of its advantages and disadvantages.

The field of extra-curricular activity is a large one, there are all the sports from fencing to football, the managerships of all the sports, the musical clubs, the players, the seven school publications, the Outing Club, the Christian Association, and numerous other activities, so that almost every man in the class has some outside interest. Most alumni are familiar with the competition in athletics. Some men are outstanding from the start and are assured of varsity positions; others work and train like slaves for four years so that in the last year they may satisfy the time requirement and secure the coveted letter. There are still others who hang on for four years never quite good enough, but hoping that a "lucky break" may afford them their chance. The role of the scrub has always been praised, but that praise gives little consolation to the man who has given two to three hours an afternoon to one or two sports for four years.

The process in other competitions is similar to that in the competition for the managerships of athletic teams. Near the close of the first year the freshman class elects thirty-five men for the athletic competition. This year there were some eighty candidates from among the first year men. Once elected the men serve in the capacity of "heelers" for a little over a year. As "heelers" they carry the water bucket, work in the equipment room, type letters for the managers and care for the many wants of the men on the teams. After this competition which is ended at the close of the sophomore year the men are elected to assistant managerships. They are chosen mainly on the basis of the effort they have put forth during the year, their willingness to work and the manner in which they performed tasks assigned to them. Other considerations are their scholastic record, personality, and indications of executive ability. The best men are made assistant managers of the major varsity sports. As assistant managers and managers in their senior year they take care of all the needs of some particular team—arranging schedule planning trips, attending league meetings, making out budgets and then trying to keep their teams within the allowance for the year that is granted by the athletic council. As managers their work is more that of the executive since they now have other "heelers" to perform the work around the gym. The competitions in other activities are much the same, varying of course with the nature of the work. Men in THE DARTMOUTH competition serve as cub reporters their first year, assistant editorial writers and managers their second year, and receive permanent appointments about the middle of the third year.

In all the competitions the process is one of elimination, and final selection of the best men for the highest offices. The original large number of freshmen aspirants after campus honors is narrowed down to the comparatively few winners, who are then eligible for election to the Green Key and to Palaeopitus and to other campus positions of honor. It is only after a man has gone through the whole process, or after he is pretty well into it, that he begins to question the real worth of his work, and wonders if he might not have utilized his time to better advantage by remaining unattached to any competition or by giving much more of his time to his studies. The scrub who has failed to win a letter, and the "heeler" who was made manager of freshman tennis might well be convinced that a greater amount of concentration on the books or a greater variety of activity with more freedom would have been a better course to follow. But not only the "unsuccessful" come to question the value of campus activity. During the last two months I have discussed the question with a number of seniors, some of them men who have attained the highest positions in their competitions, and they are likewise concerned with the question—has it been worth while? There was no unanimity of opinion and it is impossible to generalize. Some men secured much more than others, it was seldom that two men had the same experience and reacted in the same way. And then again it is almost impossible to decide what will be the basis for a judgment of the value of our extra-curricular work. Shall we judge by the practical executive training secured, by the friendships made, by the good times had, or by the definite training in a certain kind of work that has been secured. As I have stated the alumnus is better able to judge and evaluate. At best we who have been through the process can express only individual reactions and personal observations about the particular work in which we have been interested.

My own extra-curricular work has been in athletics and in executive positions on the junior and senior organizations.

The senior who is asked about his attitude towards college athletics often expresses an adverse criticism because he is still very close to the hard grind of daily practice which became more monotonous from year to year. He has probably played the sport for eight or ten years and it no longer has the same appeal to him it had at the beginning. At the close of this year's football season I heard one senior remark, "Well, I am sure of one thing, my kid will never play college football." In some fifteen or twenty years, after he has forgotten the bumps and bruises, the long practice sessions, and the loss of the Harvard and Yale games he will no doubt urge his son "to get out for the team!"

My own last year in basketball was a pleasant one and may account to a certain extent for my attitude, but I am sure that there are additional reasons. A great deal depends on the attitude with which a man approaches a sport, and the coach is able to do a great deal to determine that. At the beginning of this last season we were given what might well be called a philosophy of college athletics. In the first place, Coach Stark said that we were to play basketball for the fun that was in the game itself. He expected us to give our best during each practice session and during each game—our utmost effort, not the winning or losing was to be the essential consideration. He recognized that "the world loves a winner," and that the student body was very much a part of that world, but said that we had to make the winning secondary in order to make the season a pleasant experience. In brief, the essential thing about any game was to play the game for its own sake.

Fortified with that attitude we went ahead and had a pleasant season, although it was hard to keep our heads up under the criticism of the student body when we were on the losing end. The college body wants a winner and interprets an athletic season only in terms of the win and loss column. This, I believe, is one of the most unfortunate things about intercollegiate sport, and is the thing that may very easily make an extra-curricular career in athletics an unpleasant one. A team that can convince itself that such an attitude towards a game is a false one is very fortunate. We experienced two or three streaks of poor playing and immediately the grandstand coaches would start to explain the reason for the slump, always feeling that their observations were conclusive and absolutely correct. The fact that we did slump and were able to disregard the criticism made winning even more pleasant, and the thrill that comes when a united student body cheers a winning team would make that team forgive even the grandstand coaches.

It is true that any college sport requires a great deal of time, the struggle for a position is a hard one, constant training is essential, the bumps and bruises are many, and membership on a losing team may not be a pleasant experience. However, I believe that such training is worthwhile in itself and that there are additional favorable considerations. Four years in the locker room, on trips, on the bench, and on the floor with the same group of fellows tends to. develop a common interest and a common bond of loyalty which makes for close friendships and many happy times.

I believe that my indictment of the student body and of the alumni for their attitude towards a losing team bears repetition. I can appreciate the viewpoint of the alumnus. College athletics are given a great deal of publicity, and the alumnus very seldom sees his college mentioned anywhere except on the sport pages of the paper, so that his pride is hurt when he sees his college go down to defeat. However, the fact remains that win or lose, the athlete is doing his best and is miserable enough in defeat without having adverse criticism directed at him by the student body.

. This last year at Dartmouth has resulted in real advances being made in the field of intra-mural sports. Leagues of dormitory, fraternity, and class teams have been formed in almost all the sports. Men who play on these teams do not have to devote a great deal of time to practice, and can play the game for the fun of it. Intra-mural sports afford recreation for men who are not on varsity squads, and enable a large number of men to participate. The games are not taken too seriously and not much concern is felt over the loss of a game. I think there is a need for instilling the same spirit into intercollegiate sport in order to check the tendency which continues to put an increased emphasis on turning out winning teams.

Varsity sports do take a large amount of one's time and some men find participation in one sport enough. It is a certainty that a man can have time remaining only for his studies if he is on some varsity squad from September to June. A man who is desirous of participating in some other activity is almost compelled to limit his athletics. It is difficult to generalize about the relation of scholarship standing to athletics; some men approach probation when too actively involved in sports, others find that the regularity and the necessary utilization of all spare time when playing a sport makes for better classroom work.

As I have already stated, my other extra-curricular work was on the Green Key and Palaeopitus.

The Green Key is a junior class organization consisting of fifty men. The men are now elected by the class from nominations made by the Athletic Council, the class officers, the Outing Club, and other campus organizations. The Key acts as Dartmouth's official host to visiting athletic teams, and since its organization in 1921, its good work has come to be recognized in intercollegiate circles and a number «of colleges have patterned similar organizations after it.

The direction of the work of the Green Key constitutes a real job for the three or four men who are responsible for its organization. Athletic teams are coming to Hanover throughout the year and on some week ends there are as many as six teams in town. All of the teams must be taken care of from the time of their arrival until their departure. The Key writes to the college of the visiting team some three or four weeks before their arrival to ascertain the length of their stay, the menu for the meals, number of beds wanted at the field house, etc., etc. Committees are then assigned to the various teams and the chairman is made responsible for the entertainment of the team for the duration of its stay in Hanover. The officers of the organization are responsible for the efficient functioning of these committees. The work takes a large part of a man's time, and is discouraging when men fail to meet their assignments. However, the leadership of the organization is rewarded by the fact that the college body and certainly men who have played on the teams realize the good that the Key has done in making the college rank high for its hospitality, and then there is the additional training that is secured in directing the work and in satisfactorily discharging its responsibilities.

Palaeopitus consists of a group of thirteen seniors elected by the class. Nine of the men are chosen from nominations by the same organizations which nominate for the Green Key. Four men are chosen from the class at large. This group might be called the student governing body though there is no definite power granted to it as such. The administration has always been willing to cooperate with Palaeopitus and has welcomed any suggestion coming from that body. Among the things now taken care of by Palaeopitus are the following: it grants and manages the special train concessions, it manages a student loan fund built up from its share of the train concessions, it has charge of the freshman class organization during the first year, it audits all class accounts, it provides for dormitory chairmen who are responsible for a certain amount of order in the dormitories, it has charge of class fights, hums, rallies, class elections, etc. The organization is also called on to investigate certain problems that are turned over to it by the administration. For example, it was recently asked to investigate and express an opinion as to the proper attitude to be taken towards men who had removed books from the library without charging them. Similar problems come up from time to time and the organization serves as a representative student group upon which the administration can call at any time. It has been the policy of Palaeopitus to refrain from involving itself too much in too many college affairs, it has found it best to steer a middle course taking care of its routine work and any problems which are definitely assigned to it. I recognize the fact that the campus honor which a man receives from election to Palaeopitus is out of proportion to the actual work which he performs as a member of the organization. However, I believe the honor must be recognized as a reward for work well performed in some other field, for service to the college in some other capacity. Whether it has been worth the man's while to work through college, devoting a large amount of time to outside work, with Palaeopitus as a goal is a question that I have already raised, and one that is hard to answer.

We come now to a consideration of the relation of extra-curricular work to the requirements and purpose of the present curriculum. Men who have entered quite deeply into activities during their first two years find that by the time they reach their junior and senior years they have time to meet only the bare requirements of the professor. Extra-curricular work piles up like the proverbial snow ball so that men who have done well in athletics, or who have been elected to managerships are asked to participate in other work as a result of their success in one field. In addition to the many activities of which I have already made mention there are the fraternities to which men are expected to contribute some active support. Such a large amount of work in addition to studies during the last two years seems to me to defeat the purpose of the new curriculum.

The curricular system that was introduced with the present senior class has two main provisions: first, a greater concentration on the student's major study during the last two years, and second, the establishment of honors courses for men who have done outstanding work during their first two years. Greater concentration in one field was provided in order that the student might become as much a master of that field as was possible in college. Previously the student had merely taken a few individual extra courses in one department without any co-ordination of his work. The student now takes two courses in his junior year and three courses in his senior in his major department. One of the courses, called a co-ordinating course, is given to the men in groups of three and four. The other feature, the honors group plan, waives the ordinary regulations for outstanding students, regulations such as hour exams and regular class attendance. The honors men meet with their professors in small groups once or twice a week. Greater independence is granted the honors man but additional work is required, and the man is expected to show a higher degree of final achievement than is shown by the average student.

The opportunities for intimate discussion of a subject with a tutor, and a really thorough study of one field that the system offers appeals to most men as they approach their third year. The increased library facilities, and the small conference rooms of the new Baker library are a real assistance to the new plan. However, many men in my class found that at the same time as the demands of their major work required more of their time, they were becoming increasingly involved in the extra-curricular work into which they had launched so enthusiastically as freshmen. An efficient operation of the new curriculum, I believe, does demand an increased amount of time from the average student as well as from the honors student, and many men would be willing to devote such extra time to their work.

The only solution which suggests itself is some method of limitation of extra-curricular work. Such limitation has gone to the extreme at Cornell where very little time is allowed away from the studies. I would not advocate such a complete restriction, but would suggest that some plan be devised which would make participation in the last two years harmonise more satisfactorily with the new curriculum. A point system might be worked out providing a definite number of points for each activity, and a total of points beyond which one individual could not go. Some might object that this would unfairly curb the liberty of the student who is able to do well in his studies even though he is very active on the campus. For most men, I believe such a limitation would be a granting of increased liberty and freedom. As I have already indicated men are drawn into many things during their last two years because they have done well in some other work. A plan such as I have suggested would make them free from such increased demands on their time. In answer to the objection that men would do no additional work in their studies, we can only say that the trend of educational policy is towards self-education and towards putting most of the responsibility on the individual, and I believe that the men are coming to recognize this responsibility. The honors system and the recently announced Senior Fellowships are a part of the new policy.

From this hodge-podge of description and criticism of extra-curricular work, I hope that the alumnus can get some idea of its present significance on the campus. As I have indicated some of us are of the opinion that the studies and outside work are not properly balanced in the campus scale of values and consequently not in the amount of time devoted to them by the student. The problem is by no means an acute one, but I think it does exist. If a proper balance is maintained I believe the college is best able to train men for efficient leadership.

CARL B. SPAETH

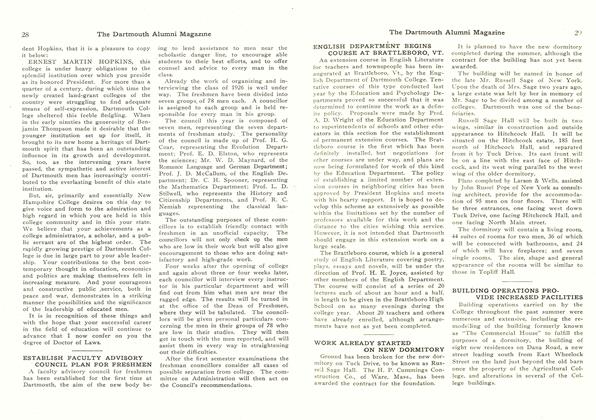

THE 1929 PALAEOPITUSFirst Row—Dudley W. Orr of Concord, N. H., Manager of Track; Albert C. Bertch of Grand Rapids, Mich., Manager of the Musical Clubs; Carl B. Spaeth of Cleveland, 0., President; Arthur P. Clow of Terryville, Conn., President of the D. C. A.; Joseph J. Ruff, Jr., of Ham- mond, Ind., Business Manager of The Dartmouth; James W. Hodson of Waterbury, Conn., President of the Players. Back Row—Freder- ick W. Andres of Arlington, Mass., President of Interfraternity Council; Richard B. Sanders of St. Paul, Minn., President of the Outing Club; John W. Bryant of West Newton, Mass., Captain of Swimming; Richard W. Black of Pekin, Ill., Captain of Football; Robert W. Austin of New York City, Basketball. Not in 'picture—Robert S. Monahan of Pawtucket, R.I., Captain of Cross Country; Walter L. Scott of New Rochelle, N. Y., Editor of The Dartmouth.

CAPTAIN OF CAPTAIN OF BASKETBALL

THE 1927-28THE 1927-28 GREEN KEY The junior organization which entertains visiting teams and which is largely responsible for the reputation for hospitality enjoyed by Dartmouth among other colleges.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

May 1929 By John R. Burleigh