The Department of Biography

There are so many advantages to be gained in one's lifeby reading of the careers of other men that this introduction is almost superfluous. Plutarch's Lives, as an example, has been a booh which has inspired many men toembark upon careers worth while. And with the newmovement which swept into the world after the publicationof Lytton Strachey's Queen Victoria a number of years agothere has come a direct movement inside our universitiesand colleges to make the study of the lives of worthwhilemen and women a distinct subject in itself. ProfessorAmbrose W. Vernon associated with the college a numberof years ago returned to the college after having establishedcourses in biography elsewhere, and at the present time theinterest of the students in the direct study of human life andhuman lives is quite marked. The study of biography assuch is rather a new subject, but the cultural value of suchstudy is one of the oldest values in the humanistic conception of education. The Renaissance brought with it a newenjoyment in the study and contemplation of art. The newinterest in biography as a subject goes back to the fundamentals,a study of the creators of art,—and as well thecreators of new ideas, new schools of thoughts, new governments, new worlds.

The courses offered by the department of Biography seek to train men for no profession; to offer no infallible formulae for explaining life or the history of it; nor to announce ex cathedra the prime factors of personality. Nor do they, on the other hand, attempt directly to train students in the technique of writing biographies, saleable or otherwise. What the programme intends, in the main, is to conduct a critical and appreciative examination of several personalities demonstrated by history to be effective and important members of the human race. But in this examination, though valuable hypotheses should develop, all attempt at classification or generalization is scrupulously deferred, however systematic the study may try to be. The only attention paid to current generalities about greatness and great men is to include some of them in the list of specific questions applied by the student to each figure in turn as a means for assisting the organization of his notes, and of his own practical philosophy of life. Let us assume, for example, a popular idea that genius lives in a weak body. In the list of questions will appear "How would you describe his physical constitution?" Then after some half dozen figures have been considered, there may occur in the final examination, such a question as: "What might we conclude, on the basis of the men studied in this course, about a connection between physical health and 'greatness?' "

From this somewhat trivial example one may gather that one function of the programme is to discipline generality by evidence.

HOW BIOGRAPHY IS TAUGHT

The method in general is to provide reading material with special emphasis on what the characters say for themselves in letters, speeches, diaries and autobiography. The response to this reading takes the form of propositions on interesting points, presented by the students and debated upon informally after most of the material has been absorbed. A division is often taken by vote on these propositions; and in the written report that concludes the study of each figure, it would seem that the burden of proof should be assumed by holders of minority opinions even more resolutely than by those of the happy majority.

All of the courses but one are conducted in much the same way, though a second semester course may modify the questions in response to general tendencies or interests shown by the first semester students who may form the nucleus of the new course. Though the only prerequisite for any of the courses is Senior or Junior standing, there is room for progress in the method if the nucleus justify it.

Not all the courses are offered every year, the interest of the department being to make the studies intimate rather than to "cover a field." The divisions, of course, are somewhat according to epochs—Earlier or PreChristian Antiquity separates itself from Later Antiquity. In the former may be considered such men as Akhnaton, David, Jeremiah, Socrates, Alexander, Confucius, Buddha and Caesar; and in the latter men like Jesus, Seneca, Paul, Marcus Aurelius, Mahomet, and Augustine. Some latter day traducers of the College might enjoy the request of one student in 1925 when there was a choice between taking Paul or MarcusAurelius next. "Let's take Marcus Aurelius, I'd like to study a great man who isn't bothered with his soul and religion." One can imagine his later disillusionment.

There is the "Modern Europeans" course which, like the others, deals with recognized leaders, but, like them too, may substitute one figure for another, since the repertoire is bigger than the schedule. Such a course would consider "What kind of men" were Frederick theGreat, Voltaire, Rousseau, Robespierre, Mirabeau, Beethoven, Goethe, Napoleon, Pasteur, Tolstoi, Garibaldi and others, according to the limits of two semesters. There is a one-semester course in Representative Modern Americans, one in Representative Men of England, and this year there is an experiment in a slightly different direction.

The experiment is listed in the catalogue as Biography 15: Representative American Careers. In it the possibilities of life offered by each of ten fields of endeavor are considered by means of biographical material. The scholarship is less intensive as there are more men considered. Take the legal career for an example. Professor Stone of the Department of Political Science gave two lectures: one appreciative of the life of Daniel Webster as a student and lawyer, and the other dealing with the more mature part of the life of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Meantime the class read Fuess' life of Rufus Choate, and presented papers reporting on it according to rubrics suggested by the chairman. At the third meeting when the papers were handed in, there was a class discussion of significant points and problems. The fourth meeting which follows a public address by Newton D. Baker on The Ideals, Opportunities andDifficulties of the Legal Career, consists in a closeted discussion, with the speaker in the witness box, as it were. This is a sample unit of the programme.

Disadvantages in this course center around the limitation placed by time on the sources of information on any one figure. There is also the obstacle that only the great biographies are thoroughly critical and fair. Obviously few such biographies are available for any modern course. The possible advantages of the experiment, however, seem to warrant the attempt. It may help men to choose a profession wisely, or see more clearly along the road they have already chosen. Certainly there is a chance to gain tolerance from understanding something of problems met by one's fellows in other professions. The main reason for mentioning here the difficulties is to temper a little the deceitful ray of novelty and to challenge the attitude of those who hail any innovation as a desirable break in the dam, and one through which all potential energy should straightway be made to gush.

Disregarding for the moment the last mentioned experiment, fundamentally the systematic study of the lives of several historic individuals, considered as characters and not as facets or details in social and literary movements, may lead to by-products of only less value than the examination of great personalities, and the general conclusions that suggest themselves in the process. Not the least of these by-products is an introduction to the appreciation of biographical literature.

THE AIM OF THE COURSE

This article started with several negative statements. Perhaps it should close with at least one positive suggestion. Bearing in mind the dictum of William James, that the differences between men are very small but exceedingly important, one may recall Goethe's conclusion that "man is the most interesting subject to man, and I begin to think the only subject that should command his attention." One can hardly succeed in dissecting any living thing, much less in analyzing the prime factors of personality. But it is certainly worth while to bring one's prejudice, ethical theories and religious conviction to the bar of the outstanding figures of one's race, to listen to the decision of the court, weighing well the dissenting opinions, and in its light to review one's attitude to the fundamentals of life. This is what may be called the subjective aim of worthy biographical study. And the objective aim, never strictly separable, is to penetrate as deeply as possible to the center of great personalities, to the inviolable ground, and there, if need be, to put off the shoes from one's feet.

DARTMOUTH HOTEL IN 1870

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Survey of Undergraduate Activities

May 1929 By Carl B. Spaeth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen

Article

-

Article

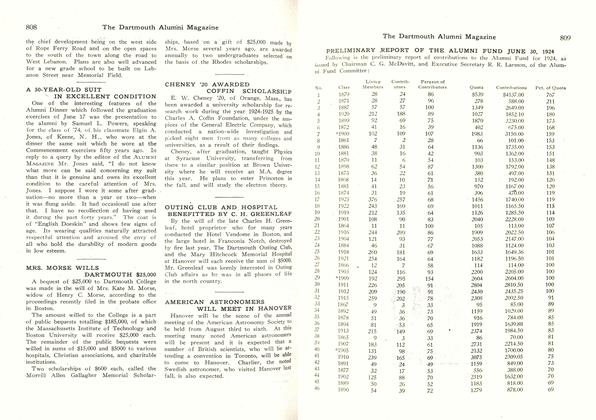

ArticleAPPLICATIONS FOR ADMISSION TO DARTMOUTH

July 1920 -

Article

ArticleMRS. MORSE WILLS DARTMOUTH $25,000

August 1924 -

Article

ArticleMarine Corps Specialists

February 1943 -

Article

Article$3-Million Leverone Bequest

FEBRUARY 1973 -

Article

ArticleDying to Get In

July/Aug 2003 By Julie Sloane '99 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

APRIL 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER