The Great President of the College Who Was Ninth in the Line of Succession Established by Dr. Wheelock

IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY William Jewett Tucker, ninth President of Dartmouth, has much to say about the traditions of the College. They were a part of him. An alumnus of Dartmouth, later a trustee, for sixteen years President, and for another decade a resident of Hanover, he had known these traditions as living realities. Throughout his administration he felt their momentum. He took care to see that they were transmitted to the "New Dartmouth." And he left this priceless endowment enriched by his own stewardship. Therefore it is in order, as it would be to his liking; to begin by recognizing him in the line of "The Wheelock Succession"—as he called it. "I believe," he said when Dr. Nichols became President, "that the greatest possession of the College has been and still is the spirit of Eleazar Wheelock in so far as it has been transmitted through his successors."

In Dr. Tucker's description of "The Traditions of Dartmouth" one sees, as having heard of them before but as never having met them, the three stalwarts of "the heroic period of the history of the College": Eleazar Wheelock, Daniel Webster, Francis Brown. The first, "Founder of Dartmouth," sixty years old, is portrayed as embodying the "creative and energizing spirit" of the eighteenth century. The second, "Re-Founder of Dartmouth," thirty- seven years old, is the "victorious champion of what had been a mightily imperiled cause." The third, President of Dartmouth at the age of thirty, elected in 18x5 to guide the institution through the turmoil at home while its fate hung in the balance at Washington, is placed with Daniel Webster as having given "an exhibition of equal courage of a different type. ... .The struggle cost him his life, but he died at his post."

In connection with the laying of the corner stone of the second Dartmouth Hall by the Earl of Dartmouth, in 1904, there was a visit to the grave of Eleazar Wheelock in the College Cemetery. "The founding of this College," said President Tucker, "is a witness to the power of a courageous, persistent, indomitable faith The writer of his epitaph has caught the spirit of his life. Beginning as a record it ends as a challenge. I have often read it to invigorate my own soul."

By the gospel he subdued the ferocity ofthe savage; And to the civilized he openednew paths of science. Traveler, Go, if youcan, and deserve The sublime reward ofsuch merit.

TRADITION AS DISCIPLINE

"I have made much account of the traditions of Dartmouth," continues Dr. Tucker in his autobiography, "because they retain their influence They form part of the Dartmouth discipline. Unconsciously, doubtless, to the average undergraduate, but none the less truly, they are a vital element in the intellectual and moral atmosphere which surrounds him. Their ultimate effect, however, is manifest in the graduates of the College I have been greatly interested in observing how surely the traditions of the College, if by any chance they have been submerged under the passing enthusiasm of an undergraduate generation, reappear in the graduate of after years."

Characteristically, Dr. Tucker has less to say about himself, in his autobiography, than about the institutions, movements, and forces with which he was identified. He calls the book My Generation because he is to give an account of his experience chiefly as related to what took place in the world during his life-time. It was a span of life reaching from the Van Buren administration in the eighteen-thirties, more than twenty years before the Civil War, to the Coolidge administration in the nineteentwenties, eight years after the World War. Seen in this perspective, "The Dartmouth Period," as he calls the sixteen years of his administration, looks surprisingly brief, and the College itself finds its proper place in the life of the country. Nevertheless, he gives to the College and to the period of his administration their due share of attention as measured by their personal importance to him, as to alumni of Dartmouth.

Dr. Tucker completed My Generation in his eightieth year, seven years before his death in 1926. He was living in Hanover, in the house built on Occom Ridge for his occupancy after retiring from the presidency in 1909. His health had been so impaired in labors for the College as to place him under severe restrictions physically. Mrs. Tucker was eyes and hands to him for a long period of years. But if one may judge from the size, scope, structure, and temper of this autobiography, he was still in full vigor mentally.

Not in the undergraduate years, as he says, but only in the maturing experience and thought of the graduate of after years, does one begin to comprehend the value of the traditions which are in the intellectual and moral atmosphere of the College. This growing appreciation is in part automatic. So often does the Dartmouth discipline make itself felt in the course of a man's life, so effectively does it come to his rescue in crises, that his awareness of it increases, and with awareness his sense of indebtedness. But the degree of appreciation is heightened when one gives thoughtful attention to a study of the Dartmouth heritage.

"RECONSTRUCTION AND EXPANSION"

How much richer this heritage now is, by reason of Dr. Tucker's personality and his achievements for the College, cannot be estimated adequately. Seventy-five years had passed since the crisis in which Daniel Webster and Francis Brown defended Dartmouth, and another crisis had come, early in the eighteen-nineties. There was the imperative necessity of "reconstruction and expansion," to use Dr. Tucker's own words, in meeting the requirements of modern education, as against the alternative of becoming obsolete. There was the problem of preventing the threatened alienation of alumni interest by effecting alumni representation in the government of the College, on the Board of Trustees, a problem involving "long and bitter discussion through preceding administrations." There was the danger of the temptation to make a university out of Dartmouth, following the example of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, instead of holding to the distinctive function of a college. And there was the seemingly insoluble problem of finding, as a successor to President Bartlett, an alumnus equal to the emergency. Three times William Jewett Tucker was asked if he would accept the presidency before he finally acceptedin 1876, again in 1892, and, after a year of unsuccessful search in other directions, once more in 1893.

Having served as a trustee of the College for fifteen years, Dr. Tucker knew the situation both inside and outside. His reluctance in accepting the call was partly because of uncertainty as to his fitness but more because of a sense of obligation to his position at Andover Theological Seminary. What would have become of Dartmouth if he had not accepted, calls for a lively exercise of the imagination. What did take place is a matter of history. Dr. Tucker's present title is the "Founder of the New Dartmouth." "Without him the Dartmouth of the present day would have been per- fectly impossible," writes President Hop- kins in 1938, in a letter referring to his own efforts to "make evident to the younger alumni the living truth of how greatly they are obligated to Dr. Tucker for laying the foundations, furnishing the vision, and starting the building of what is the modern college."

Fuller acquaintance with Dr. Tucker's contribution to the Dartmouth heritage is to be had in several ways. One is by looking at the College itself with him in mind. Nineteen buildings were constructed during his administration. The water system, the lighting service, the central heating plant were installed. The value of the college properties, not inventoried in the report of the Treasurer for 1893, was advanced to $3,956,000 in 1908. The earning power of the College rose from less than $20,000 net to more than $120,000 net. The undergraduate enrollment increased from 347 in 1893 to 1087 in 1909. The geographical distribution of the student body was extended from New England in the direction of a national constituency: the percentage from outside New England in 1893- 1894 was less than fourteen per cent, and in 1908-09 more than twenty-six per cent. The curriculum was enlarged and the faculty increased to meet the requirements of modernized education. These are the tangibles. The intangibles, which are of greater importance, baffle any attempt at either summary statement or detailed description. They are to be told only in terms of human values, the morale of the College, its renewed vitality, its quickening influence upon the undergraduates, its expanding influence across the Nation and across the seas.

DR. TUCKER'S WRITINGS

In addition to these tangible and intangible effects of Dr. Tucker's leadership, and as sources of information concerning not only his administration but also the College, the man himself and his mind, there are six books bearing his name as author. Listed in reverse chronological order these books are: My Generation, An Autobiographical Interpretation, 1919; The NewReservation of Time, Articles Contributed to the Atlantic Monthly during the Occupancy of the Period Described, 1916; The Function of the Church in ModernSociety, 1911; Personal Power, Counsels to College Men, 1910; Public Mindedness, An Aspect of Citizenship Considered in Various Addresses Given While President of Dartmouth College, 1909; The Makingand Unmaking of the Preacher, Lectures on the Lyman Beecher Foundation at Yale University, 1898; The New Movement inHumanity, From Liberty to Unity, Phi Beta Kappa Address at Harvard University, 1892. This list does not exhaust the published writings. Numerous addresses, as well as articles and editorials contributed by Dr. Tucker, are in existence in pamphlet, periodical, or book form. Hymns ofthe Faith, used for a number of years in the College Chapel, bears his name as editor. And the number of manuscripts still unpublished is presumably large.

SIXTEEN YEARS A PRESIDENT

William Jewett Tucker was fifty-three years old when he accepted the call to the presidency of Dartmouth, fifty-four when he presided at the opening of college in September, 1893. When he withdrew from the presidency in 1909, he was in his seven- tieth year. "Retired" is hardly the word, for in the seventeen years between the close of his administration and the close of his life Dr. Tucker, though physically less active, was mentally so alert and so productive as to add another full chapter to his career. Before his election to the presidency he had already rendered distinguished service in the Congregational ministry. For thirteen years he was Bartlett Professor of Sacred Rhetoric at Andover Theological Seminary. It was during this period that he was instrumental in establishing in Boston the social settlement now known as South End House. It was also during this period that the famous Andover Controversy took place, involving Dr. Tucker with four other members of the Andover faculty as charged by the Board of Visitors with heterodoxy, and culminating in a trial before the Supreme Court of Massachusetts. (Actually the trial was first before the Board of Visitors of Andover, and the controversy before the Supreme Court was on the question of whether the Visitors in that trial had exceeded their jurisdiction, as set forth in the Andover charter.) The verdict was acquittal for four of the five professors and a dismissal of charges in the case of the fifth.

MRS. TUCKER

Dartmouth men who were in college thirty and forty years ago are not likely to forget the woman who held with complete fitness the honored position of the President's wife. It was at Andover that she and Dr. Tucker had their first home. He wrote:

"I cannot forget, though thirty-two years have since passed, that it was into the Andover home that she brought those rare gifts of mind and heart which were to make her life so personal and distinctive through the coming years, and yet so unreservedly and so vitally a part of my own; the perfect sincerity underlying the engaging frankness of her manners, the maturity of her understanding and her quick intelligence, her unaffected loyalty to things right and true, her just appreciation of others, and the steadfastness of her personal devotion."

Prior to the Andover period Dr. Tucker served five years as pastor of the Madison Square Presbyterian Church in New York City, and before that, seven years as pastor of the Franklin Street Congregational Church in Manchester, New Hampshire; this was between the ages of twenty-eight and forty-one.

"It was there," he writes, referring to the Manchester pastorate, "that I learned that first and most imperative lesson of the pulpit—to respect one's audience; "not to fear it, but to respect it It was of peculiar advantage to me that I began to preach to an audience of severe intellectual demands, as I was endeavoring from the first to train myself to the freedom of direct speech in the pulpit, without the habitual use of manuscript or without reliance upon verbal memory. I knew, that the spiritual abandon which the truth in hand may call for, was unsafe and ineffective unless the preacher could assume the steady and reliable support of clear, terse, and truthful speech—speech which would not weaken and disperse his emotional power Whatever of freedom I may have gained in the pulpit or on the platform, I owe to the patient and sympathetic help of those in my first pastorate whose insistence upon the realities of speech was not to be misunderstood." This preacher was also a teacher, engaging his congregation in the direct and original study of the Bible. And under his leadership the Manchester congregation extended a ministering hospitality to the operatives of that manufacturing city. "Perhaps the most interesting feature of the development of the church during this period was its social expansion, or expansion in the direction of democracy."

"I recall with much distinctness and even vividness my first Sunday in the Madison Square pulpit As I faced the audience which thronged the church, I found myself steadied and quickened by the sensitive and apparently eager response to my message It was a message to the modern man asking where and how he might find God—not at first and chiefly in the past, but in the present, not among the dead, but among the living." The New York congregation to which Dr. Tucker ministered included Cyrus W. Field of Atlantic cable fame, Samuel J. Tilden, Governor of New York and Democratic candidate for president, two mayors of New York City, and others prominent in business, professional, and public affairs.

As we follow the course of Dr. Tucker's life still further backward toward its beginnings we find ourselves in the period of the Civil War. 1866 was the year of his graduation from Andover Theological Seminary, 1861 that of his graduation from Dartmouth. "It has been a lifelong regret to me that I was precluded by a succession of prohibitive conditions, beginning with the disability resulting from a prolonged attack of typhoid fever, from any active part in the War till near its close, and then only in a subsidiary way." This subsidiary way was in the service of the United States Christian Commission in Tennessee and Georgia, accompanying soldiers on the march and in camp, and assisting in the care of the wounded. For a time after graduation from college Dr. Tucker taught school in Columbus, Ohio, and for a portion of a year after graduation from Andover he was in the service of the American Home Missionary Society in Missouri and Kansas.

In his account of these working experiences in the South, in the Middle West, in New York City, Dr. Tucker makes it clear that it was New England which furnished the incentive. "My approach to my generation was through the New England home and the New England college. I am still conscious that these gave me not only the early point of view, but initiative, direction, and restraint." The birthplace was Griswold, Connecticut; the year of birth, 1839. After the death of his mother, the eight-year-old boy found himself in a new home, with his nearest of kin, a younger sister of the mother, Mrs. William R. Jewett. The uncle by marriage was a Congregational minister, then in Griswold, later in Plymouth, New Hampshire. A time came when Dr. Tucker was able to make return in kind for this mothering and fathering at the hands of the Jewetts. "They had spent their winters with us in New York and the Andover home was theirs to the end." So it was in New Hampshire that Dr. Tucker spent all but the first eight years of his boyhood and youth.

"The home life of that period as I saw it had found the normal balance between authority and indulgence Whatever the Puritan home may have been aforetime I know only by report, but when it became the home for my generation, it stood for a natural, intelligent, and reasonably free approach to the world."

INAUGURAL ADDRESS

There are now living more than 700 alumni who were of college age or older at the time of the inauguration of Dr. Tucker as President of Dartmouth, in June 1893. A considerable number of these seven hundred were present on that occasion and heard the inaugural address. Here are three of its memorable passages:

"Within the past year the phrase has become current amongst us,—the new Dartmouth. I interpret the phrase to express our decision and our enthusiasm in the work to which we are called in the readjustment and development of Dartmouth. And yet let me say at once, we cannot make too great an acknowledgment of that which has been done before. The chiefest factor in the new will be the old. Each administration of the college, from the first to the last, has made its own contribution, more often than otherwise in self-denial and sacrifice. We build upon strong and wide foundations."

"Gentlemen of the college, of the past and of the present; as we in our own persons increase in years, though it may be for long time with augmenting strength, we know the inevitable limit. The life of an individual cannot attain to the dignity of history. The approach to that dignity marks the lessening of one's future. It is not so with the life of a great institution. The historic college moves on from generation to generation to its illimitable future. Each generation waits to pour into its life the warmth and richness of its own, and departing, bequeaths to it the earnings of its strength. The college lives because nourished and fed from the unfailing sources of personal devotion."

"I congratulate you, gentlemen, as the living embodiment of the college, upon the present signs of personal devotion to Dartmouth. It is evidently as true now as when the words were uttered,—'There are those who love it.' May there be now and always the like wisdom in those who are called to serve it. If that can be assured,— and may God grant it,—the place of Dart- mouth College in American letters and learning is as secure for the future as in the past."

TUCKER THE MAN

There are nearly two thousand alumni now living who attended Dartmouth during Dr. Tucker's administration. These will readily recall what manner of man he was: the natural dignity of his presence; the quality of his voice; his command of English; his respect for others, and theirs for him; the clarity of his thinking; his wealth of wisdom; his sub-surface enthusiasm; the constant undercurrent of controlled and directed emotion; the sense of his power in action, and of his power in reserve; his confidence in himself, free of egotism; the range of his vision—far ahead into the future and far back into the past; his mastery of the immediate situation; his enduring faith in Dartmouth, in the men of Dartmouth, in mankind; his recognition of the achievements of others than himself; his self-sacrificing devotion to great purposes; his religion—sincere, searching, luminous, convincing.

Picture after picture rises before the mind's eye, out of the depth of submerged memories. One sees Dr. Tucker as he appeared crossing the Campus or approaching on the sidewalk, erect, alert, his walk that of the army quick-step, his greeting that of an officer—friendly but not effusive, with an almost military salute. One sees him in his trim horse-drawn singleseater, buggy or sleigh, alone or with Mrs. Tucker at his side. One sees him in his office in the white building which had been a residence, at the head of the Campus. One remembers him in his home on College Street, cordial in his quiet manner, a good listener. One remembers him presiding at assemblies on the opening of College in September, or on Dartmouth Night, or on other special occasions dur- ing the year, in the Old Chapel in the original Dartmouth Hall. One listens again to his sermon on Baccalaureate Sun- day in June, in the White Church. One remembers him best of all, perhaps, in Rollins Chapel, at the early morning period, or at the Sunday Vespers, apparently distant but really near, apparently impassive but actually impassioned.

It is difficult to choose from the addresses given at the opening of college, for the reason that they are all memorable. Also it is impossible to select passages from any one address without destroying its feeling of movement and its organic unity, and without sacrificing other passages equally valuable. But here are portions of the address given September 22, 1904:

"The keynote of college life is personal freedom with its perpetual joy, perpetual only as it is deepened by the sense of the obligation which one owes to himself. The college can do much for a man, but it is absolutely powerless before the man who will not learn for himself the one high lesson of self-respect. Self-respect, I say, which I trust no man among you will ever pervert into self-conceit. Conceit is a disgrace to any man, it is an unpardonable disgrace to a college man. But the selfrespecting man is quite sure to meet those obligations which make him a power for good to himself and to others. Knowing his own rights, he will respect the rights of others, and measuring the needs of others by his own standards he will contribute generously to the common good.

"I have no fear, gentlemen, for you per- personally or for the College, during the coming year, as I rest in the confident assurance that you propose to meet your obligations to yourselves as self-respecting men."

Possibly there was no single moment in the entire four years at Dartmouth more impressive for the student than that which came on the last Sunday of his last year in college, at the close of the Baccalaureate sermon. His attention may have wandered during the course of the sermon but it was brought back suddenly when the President paused, left his manuscript, if he had been reading, and spoke directly, with especial earnestness:

"Men of 1903"—the whole class stoodto receive the farewell message—"l greet you, as you stand with the future in your hearts. You are putting behind you the years of college life. This is right. It is time for you to be elsewhere and about other business. These college days, these college friendships, these college ideals will abide with you. There is no doubt about that. Nothing will ever take their place, for there is nothing which can take their place. But you have to do with other men in other ways, and for other ends. You have to do with work which waits your own initiative. Do not be afraid of men. Respect men, all men, but fear no man. Respect your work and honor it. Do it without a trace of impatience, or without the slightest taint of dishonesty. Do not be afraid of work.

"Fear nothing but your own weakness. Now is the time for every man to have a full reckoning with himself, and if never before, to organize himself for the whole of his life, f have tried to tell you who is the well-organized man—the man of faith, who carries the sense of the hereafter in his heart; the man capable of action among men of mere activities; the man who is the master of his desires; the man who loves truth.

"I do not believe that such a man will fail, but if he fails, I would rather have his failures than the success of men without principles. And I believe further that the modern world wants this man above other men, or will make room for him, or allow him to make room for himself in the jarring crowd. So I bid you go your ways to live without fear and without reproach among your fellow men, and to walk humbly with your God."

CHAPEL TALKS

The selections which follow, taken from issues of The Dartmouth over a period of four or five years, are arranged according to subject matter rather than chronologically, and are given in condensed form:

"This college was possible when Eleazar Wheelock took the Berkeley Fellowship at Yale, when he began to teach the Indian boys—as soon, in fact, as he became clothed with a great purpose You and I and the thousands who shall follow us may look upon this College as an example of what a man may accomplish when he casts his lot in with a great purpose and lets it bear him onward."

"The supreme question in the relation of a man to his world is this—not what he gets out of it, but what he puts into it."

"Some of you propose to go into the money-making callings. They have immense power for good. I do not warn you against them. I do apprise you, with all the earnestness in my power, of your responsibility. No man who is indifferent to the moral value of money today has any business with it."

" 'Honor thy father and thy mother.' We owe at all times and in all circumstances, the honor of loyalty. If any man makes a personal advance upon the family estate, let him not forget those from whom he sprang. Let his fortune be their fortune. And if on the other hand his personal inheritance is of high honor, let him have a constant care that he does not dishonor the family name or the family traditions. Whoever fails to keep the fifth commandment, in the fullness of its spirit, fails at the deepest point in our common humanity."

" 'Thou shalt not commit adultery.' This commandment stands for the transmission of 'pure, untainted blood.' It keeps guard at the gateway of parenthood. In no other way can the sins of the father be visited so surely upon the children to the third and fourth generation as through the violation of the seventh commandment. A man of thoroughly poisoned blood has no right to marriage. He thereby condemns himself to an unworthy solitude. The endowment of passion is a very great endowment, as great as it is dangerous. There have been committed to it the transmission of life, the perpetuity of the family, the chivalrous devotion to woman. The way in which a man carries this endowment is the strongest test of his manhood."

If those chapel services meant much to the students, what did they mean to Dr. Tucker himself? Ten years later, viewing the experience in retrospect, he wrote in his autobiography, "The one opportunity at Dartmouth within reach of the President for definite and constant access to the mind of the College lay in the use of the chapel service, which by tradition fell to his lot. I allowed no engagement for Sunday to interfere with this fixed engagement The remembrance of the fifteen years of contact with the mind of the College, through the Sunday Vespers in Rollins Chapel, are in many ways too personal even for the pages of an autobiography. The generations of college men as they came and went, filling the rows of the chapel benches, still pass before me in the orderly procession of the years."

OF PRESIDENT HOPKINS

This is not the place for an adequate tribute to President Hopkins, much less for an appraisal of his masterly and still progressing administration. It is fitting, however, to see him in "The Wheelock Succession." He has been at once a follower and a leader, embodying the "creative, energizing, pioneering spirit" which Dr. Tucker noted as chief among Dartmouth traditions. There are several ways of accounting for the fact that these two men appear together as one looks in the direction of Hanover. President Hopkins never tires of calling attention to our common indebtedness to Dr. Tucker: "All of the development pertaining to the College of the present day was made possible because of his breadth of view, his depth of insight, and his constructive imagination More than can be said of the work of any other man in Dartmouth's long history, the College of today is his.

President Tucker was the greatest man I have ever known." At this distance the two men seem to have been almost as father and son. While still in college, "Hop" was elected by his fellow-students to such positions of leadership—class president, editor of The Dartmouth, member of the Athletic Council—as to cause him to be naturally in frequent communication with the President. After graduation he was chosen to be private secretary to the President; later, Secretary of the College. It was, to say the least, an experience in discipleship. The paragraph which follows is from My Generation:

MEETING THE TESTS

"It was to be assumed from my intimate relations with Secretary Hopkins that I should be peculiarly interested in the course of his administration when he was called to the presidency. I have been much more than interested. President Hopkins was confronted on his entrance upon his administration with those serious though general problems which had been already created by the War. Within a year the country itself was at war and the colleges became directly involved in it; at first, through their voluntary response to the call of the Government; later, through their militarization. As I have followed the course of President Hopkins in these circumstances, I do not know whether he is entitled to greater respect for the loyalty of his personal services to the Government or for the sagacity of his management of the College—the boldness of his financial plans, the firmness of his adherence on behalf of the College to its educational standards. Many tests of educational leadership now await the presidents of our colleges, but the tests already made in the administration of President Hopkins give reason for confident assurance respecting the future of Dartmouth."

That was twenty years ago. It is more than probable that Dr. Tucker would now be saying that he was not mistaken in his "confident assurance," and that the onMuward movement of the College has far exceeded his own expectations.

It is June, 1909, Commencement. Dr. Nichols has been made President of Dartmouth. Dr. Tucker is not well enough to take part in the formal exercises. He is able to be present at the Alumni Dinner. He has something to say. It is, though he does not call it so, his valedictory. He does not say that he is deeply affected, but one can see that he is, one can feel it in the words, one can read it between the lines:

"Very naturally my thought runs today to the relation between the transient and the permanent in our college life. This question of the transient and the permanent confronts us everywhere, but nowhere I think does it reach so happy a solution as here; for here we not only see, but feel, that the transient goes over into the permanent so naturally, almost so imperceptibly, and with such compensating joy that hardly a sign is left of the change. And this for the very simple reason that a college is not so much an institution as it is a movement, a procession.

. . Here, for example, are two hundred men who are today passing out of the transient into their relatively permanent relation to the College Always in the background of this steady movement of life stands the ancestral home When our hearts turn hitherward, we must not be afraid of sentiment. Let the mother of us all know, by visible and enduring signs, that you love her. Let her never be made ashamed, in any respect, for herself, not simply for her sons, as she stands with the years falling upon her in the midst of the older and the younger colleges of the land. Better yet, see to it that her strength is as the strength of the hills which guard her, and her beauty like their beauty, simple, true, sufficient."

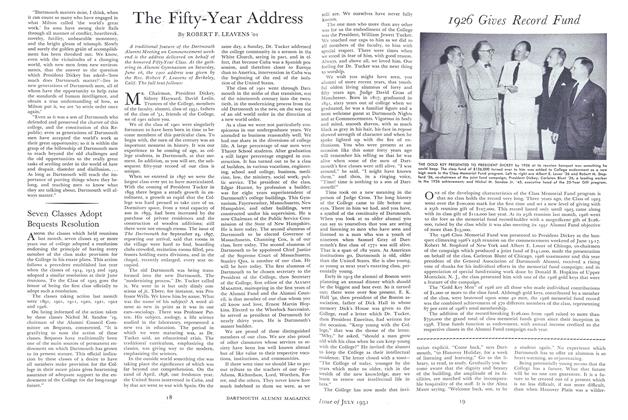

William J. Tucker

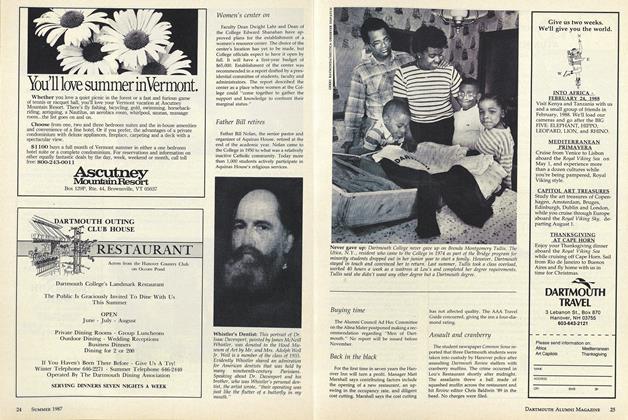

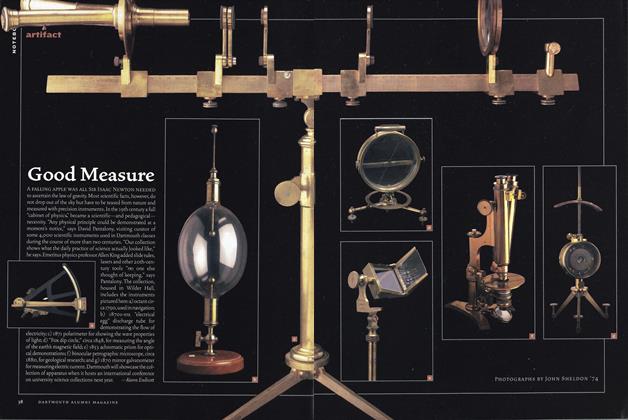

WILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER '6I, POSTHUMOUS PORTRAIT BY J. D. KATZIEFF

[This year, 1939, marks the one hundredthanniversary of the birth of William JewettTucker, ninth President of Dartmouth. Ithardly seems possible that this is so, because it is only a little more than twelveyears since he died, and because to thosewho knew him he can still be seen andheard, in living memory. Debtors to him asall Dartmouth men are, the occasion callsfor at least a pause, in recognition. It alsoaffords an opportunity to renew and extend the acquaintance, an experience madepossible by the fact that Dr. Tucker lefthimself in writing. Having chosen at firstthe spoken word as his profession, and having excelled in that function to the degreethat his sermons and addresses made goodreading half a century later, he had also theability to fill, later on, a difficult and important executive position, with signal success, and yet found time to leave on depositout of his later years a few books comparable in excellence to his achievement as anadministrator.The author and editors acknowledge indebtedness to Houghton Mifflin Cos. forquoted passages from copyrighted books.Also to the Rumford Press, Concord, N. H.,for passages from Public Mindedness byDr. Tucker.—THE AUTHOR.]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

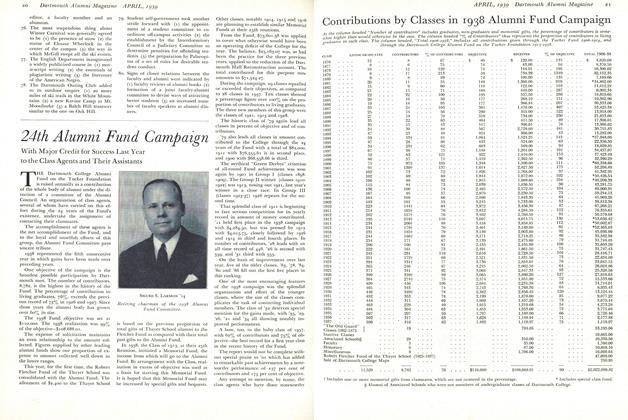

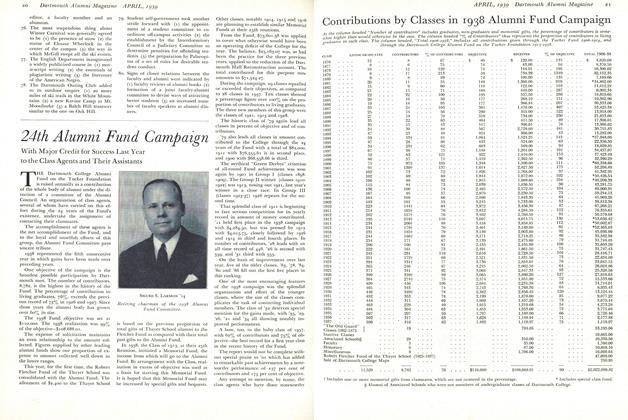

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1938 Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 -

Feature

FeatureLife of a Class Agent

April 1939 By Davis Jackson '36. -

Cover Story

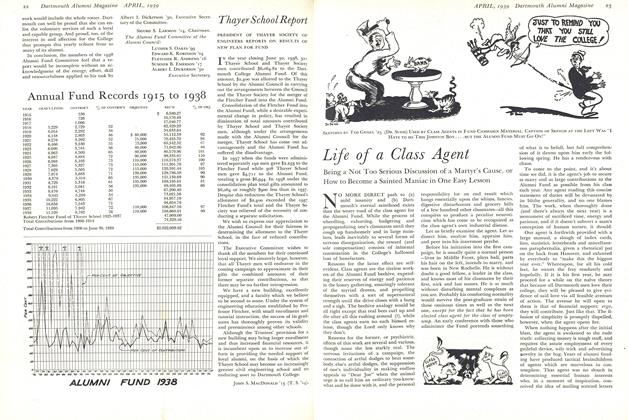

Cover Story24th Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 By Luther S. Oakes '99, Edward K. Robinson '04, Fletcher R. Andrews '162 more ... -

Feature

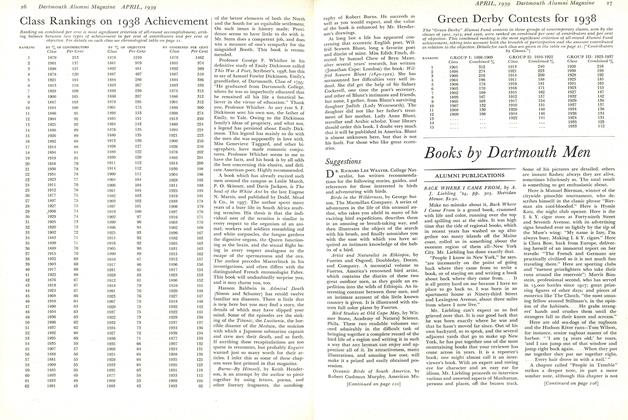

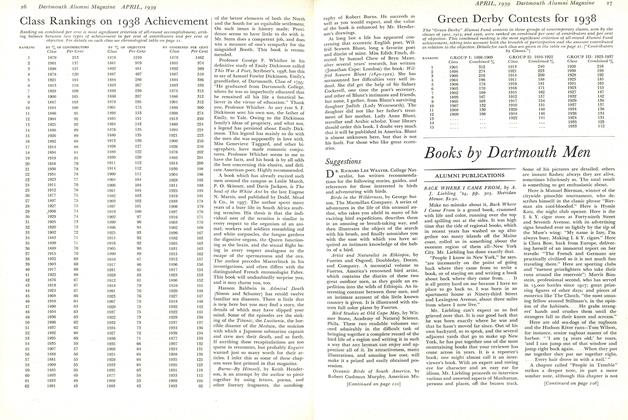

FeatureGlass Rankings on 1938 Achievement

April 1939 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1939 By John S. Macdonald '13 -

Feature

FeatureGreen Derby Contests for 1938

April 1939