An Appreciation of the Researches of ProfessorAmes and Dr. Gliddon, Research Dept. ofPhysiological Optics, Dartmouth College. By Charles Sheard, M.A. (Dart.), Ph.D. (Princ.) Professor of biophysics and physiological optics, the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, University of Minnesota, and chief of the section of Physics and Biophysical research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

On a wall of the sanctum sanctorum of a famous English surgeon and physician hangs a chart which lists the importance of the five special senses—to which should be added presumably a sixth, common sense—in medicine. First of all, and in great big letters, comes VISION and last, and truly least, is taste. We are what we are mentally in large by virtue of the information we gain through our eyes, for our brains are exposed directly to the outer world in just two places —our two eyes. The retinae contain thousands upon thousands of nerve fibers distributed over their surfaces; these fibers are ultimately bundled together to form the optic nerves which carry their messages in some manner or other to the "I am"—the feeling, thinking, interpreting self.

Investigations, therefore, regarding processes of vision and visual functionings are of the highest importance. How we see and what we see are but little understood. These problems have been the chief interest in life of but relatively few investigators. A goodly portion of the fundamental work in physiological optics has been done by the great scientific genius, von Helmholtz, Donders—who was professor of physiology and ophthalmology at the University of Utrecht—and Tscherning who, during the days of his active career, was professor of ophthalmology at the Sorbonne. A great deal of so-called practical experimentation has been carried out in the United States during the past fifty years in matters pertaining to problems of diseases of the eyes and refractive errors. It is only within the past dozen or fifteen years that a few investigators in this country, trained either as physicists, physiologists or psychologists, have directed their attention to serious investigations regarding the functions of ocular accommodation and binocular single vision. The present work of Professor Ames and Dr. Gliddon on "Ocular Measurements" is to be hailed, therefore, not only as a valuable contribution in a very important field of scientific endeavor but also as an indication of the probability that American physiological opticists will become leaders in this field. Those interested in vision, irrespective of their slant of mind on the subject and irrespective of their agreement or disagreement with the conclusions reached by the authors, can rejoice with the faculty, students and alumni of Dartmouth College in the fact that research work of this type and of such far-reaching results has been undertaken and will be continued, I hope, for many years to come.

To write this note of appreciation is only a five minutes' pleasant task. Yes, indeed, having been interested in matters pertaining to ocular refraction for nearly a quarter of a century, having known both Ames and Gliddon for several years, having visited with them and watched the progress of their work, it is a pleasure to write of their carefully planned and skilfully executed researches and to say that, like all good investigators, they have been skeptical of some of our accepted doctrines and have blazed a new trail with its consequent stimulation to further labors. To tell the readers of the Dartmouth ALUMNI MAGAZINE something about their discoveries in a manner that can be understood readily that is a real task and beyond the limits of a few hundred words. However, let me say that the normal individual is possessed of two eyes and two fundamental inborn or developed desires, namely, to see distinctly and singly at all times and under all circumstances. In order to see distinctly, and to switch the gaze, in less time than it takes to snap your fingers, from viewing a distant landscape to reading the newspaper, requires a rapidly focussing lens system. The crystalline lens of the eye, under innervation, is accommodated normally at will and if one is not too old or is not afflicted with under- or over-developed ocular systems, he can see distinctly anything from a distant object to something held within a few inches of his nose. The two eyes, each accommodating and therefore possessing normal or distinct vision, must work together as a team and must converge just the proper amount in order to allow of the fusion of the two retinal images into one. Then, too, these eyes, when converging as in the act of reading, must not tort or turn from the primary vertical meridians, otherwise the retinal images would each possess a slant or twist and normal singleness of vision could not occur, or if it did occur, only under abnormal innervation of the muscles which prevent the eyes from torting. Most pairs of eyes are not normal, and possess weaknesses of accomodation, insufficiencies or excesses of convergence and many tend to tort. Ames and Gliddon have been investigating the whys and wherefores of these anomalies and have been further elucidating the factors which enter into the familiar act of seeing singly and distinctly. If you care to learn something regarding the intricacies of vision read their, brochure on "Ocular Measurements" (68 pages) presented before the Section on Ophthalmology at the annual session of the American Medical Association, Minneapolis, 1928.

GOLD MEDAL AWARDED PROF. AMES AND DR. GLIDDON FOR EXHIBIT AT MEETING OF AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION IN MINNEAPOLIS.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Survey of Undergraduate Activities

May 1929 By Carl B. Spaeth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen

Books

-

Books

BooksSaints Legend

March 1917 -

Books

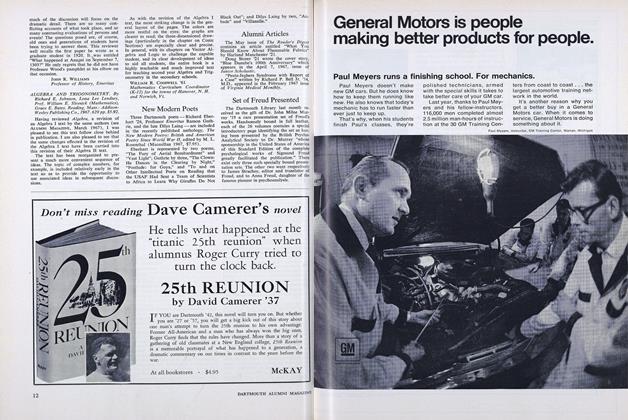

BooksAlumni Articles

JUNE 1967 -

Books

BooksShelflife

July/Aug 2002 -

Books

BooksGENERAL INTRODUCTION TO ETHICS

DECEMBER 1929 By Nelson Lee Smith -

Books

BooksTHE ENGLISH BIBLE AS LITERATURE

April 1931 By Roy Bullard Chamberlin -

Books

BooksNAVY AT DARTMOUTH

August 1946 By W. A. EDDY (1919H), Col. USMC (Ret'd)