By Norma Farber;Robert Pack '51, and Louis Simpson. NewYork: Scribner's, 1955. 195 pp. $3.50.

With commercial wisdom Scribner's has adopted a plan to give readers three new poets for a little more than the price of one, and I am glad for several reasons that the editors have included Mr. Pack in their second selection. For one thing, his images are directly accessible, made for the most part of seasons, weather, rocks, sun, birds and to a lesser extent of streets, girls, mirrors, bread, and even a zoo. Out of these latter materials of civilization he makes poems of grief and philosophy, but his better work uses objects of nature to communicate his lyrical responses not so much to nature as within it. The reader, waiting inside the poet's awareness, perceives, then apprehends as freshly as he does. "Song for the Early World" creates a dawn rich with new significance, and the following sonnet is as startingly clear:

Memory is shade: The child without The gift of guilt, only innocent To himself, yet makes his practice journeys In the landscape of his joy: those turtles, Amazing to his sight, those frogs Whose legs are handles for the hands of boys, water-snakes And water-bugs and fish that look you in the eye And dart away, are all the treasure of the earth.

He has awakened with the dawn to swim To a rock, the center of the lake, with mist rising From the water like spirits from a grave, And he has waited, silent as the mist itself, For the grandfather turtle of the lake, old as the rock On which he sat, until the summer passed.

Unfortunately Mr. Pack does not always allow the experience to emerge so nakedly and provocatively. He is likely to clutter a fine inspiration with direct statement that dulls the essential feeling. What we get instead of poetry is intellectual prosiness. And this same rational turn of mind causes Mr. Pack to turn out pieces that are uncomfortably witty. Too often, we sense, a poem is written so that it will come out "just right." Then lyricism is sacrificed to a preconceived rigidity. Rather than respond, we inspect - and find things not so "just right" after all. But seldom does a poem fail to yield at least one passage keen with both insight and verbal dexterity. We share bereavement ("My friends, your sorrow is the stone/Of his finality: what can I say"). We perceive relationships anew ("In dark an owl awaits the foreign day") and new relationships [ ("We have imitated you enough./ The nonsense of your rhetoric that has/The feel of praise, like standing in the sun,/Is our nobility." - of Dylan Thomas). In such achievement of strong lines and the talent that they mean lies all of Mr. Pack's promise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of a Liberal Education

December 1955 By PROF. ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Feature

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

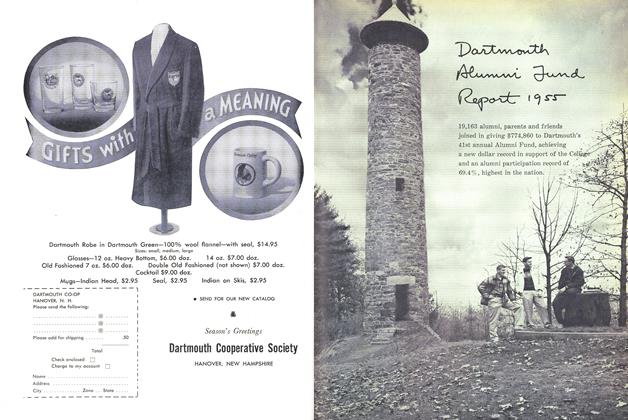

FeatureChairman's Report THE 1955 ALUMNI FUND

December 1955 By Roger C. Wilde '21 -

Feature

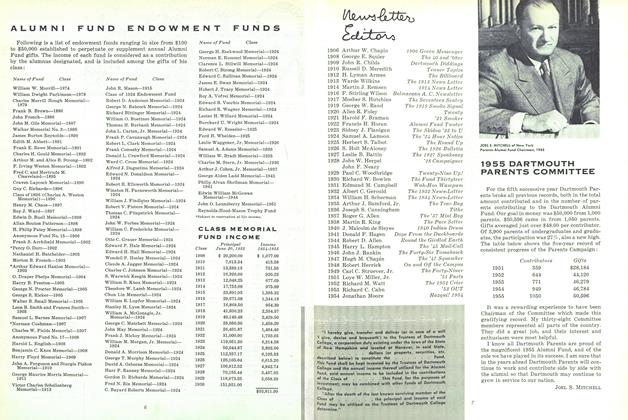

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1955 -

Feature

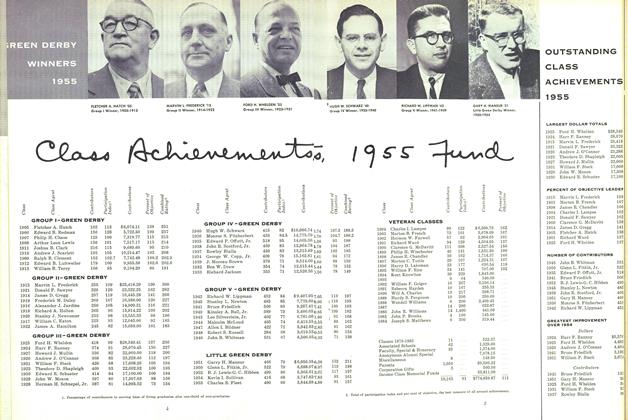

FeatureChass Achierement 1955 Fund

December 1955 -

Feature

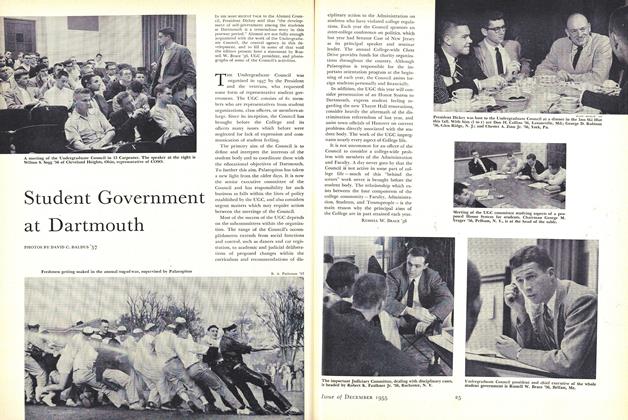

FeatureStudent Government at Dartmouth

December 1955 By RUSSELL W. BRACE '56

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

November 1956 -

Books

BooksTelevision

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

March, 1924 By David Lambuth -

Books

BooksA NAVAL LOG,

October 1945 By Homer Howard, Lieut. Comdr., USNR. -

Books

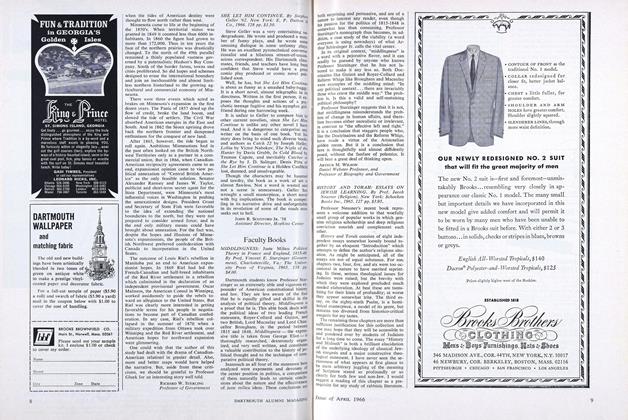

BooksSHE LET HIM CONTINUE.

APRIL 1966 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38 -

Books

BooksHALL'S LECTURES ON SCHOOL-KEEPING

MARCH 1930 By R. A. B.