By Daniel Chase (Ernest Howard Chase '14), Bobbs-Merrill Co.

Mr. Chase has wisdom. He has gone back to the soil from which a long line of New England ancestors drew their lives, and is farming it while he writes its story. He has left even the seaboard against which "The Middle Passage" and "Flood Tide" were sketched, and has gone back to the weatherscarred houses, the tired old men, and the sprawling stone walls of the back country towns that have lost their fresh, vital blood to the greedy West or to the quiet graveyard.

I read "Hardy Rye" and said, "This man is a poet, not a novelist." Now has come "Pines of Jaalam," and I confess myself wrong, for the poet is still here, but the novelist has grown. The author has tightened the structure of his work, the characters have lost the aggravating trick of acting with an unmotivated swiftness that leaves one dazed. The whole tempo of the last two novels has slowed to let act and motive move together, but in "Pines of Jaalam" the characters are fewer, and the dramatic incident has given place to the development of character. Considered from the standpoint of novel technique it is the best of Mr. Chase's work. It loses something by the hardness of its central figure, but the handling of character is surer and more deft, and the variety of personality and feeling greater.

I like most in Mr. Chase the poetic power of his writing. It is never pretty or precious, but is rich with intense realization of form, colour, and sense impression. It is a vigorous, masculine language, strong with simple and direct words that convince one of the reality of what they image. But after all, for the novel language is only a vehicle, and though I miss the frequent paragraphs of earthly beauty that marked "Hardy Rye," it was best that they go. As a novelist should, Mr. Chase has held firmly to the world of outer objects, but has looked deeper into the world of human conflicts and desires. Man is worth more than physical nature, but I am grateful for a novelist who has heard the steady chant of insect life, and caught the dim dusting of green that hints the necromancy of Spring.

"Pines of Jaalam" is the story of Lavinia Copeland, who, after her father's death, timidly sets, about her task of fighting poverty and the loneliness of Road's End. She gives her life to the place in her passion for developing it, for converting more and more scrubby acres into fields ranked with nursery seedpart lings. Her fierce determination and singleness of purpose lose her love, all the beauty of earth, and all the joyousness of living. Not until her young trees are acrid smoke and graying ash does the earth again become warm beneath her feet, and the bitterness of sterile ambition unlock its hold from, her heart.

The mystic sense of the unity of all living things, plant and human, is less pronounced here than in "Hardy Rye," but the fable of Antaeus still speaks its truth. The colour and scent of earth are softened, but New England is still here, hard and gnarled yet lovely as an old apple tree in flower.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Survey of Undergraduate Activities

May 1929 By Carl B. Spaeth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

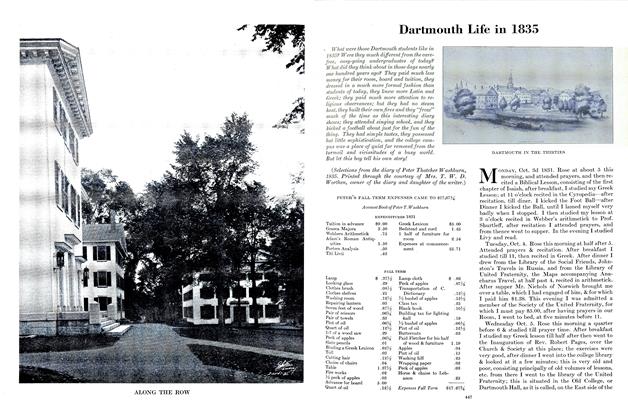

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen

Allan Macdonald.

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2005 -

Books

BooksMARINE PRODUCTS. OF COMMERCE

MARCH 1930 By B. B. Leavitt -

Books

BooksFunny Latins Chileans Are Not

May 1975 By BERNARD E. SEGAL -

Books

BooksROBERT FROST, ORIGINAL "ORDINARY MAN"

APRIL 1929 By Evan A. Woodward -

Books

BooksAUBURN, NEW HAMPSHIRE 1719-1969.

APRIL 1971 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

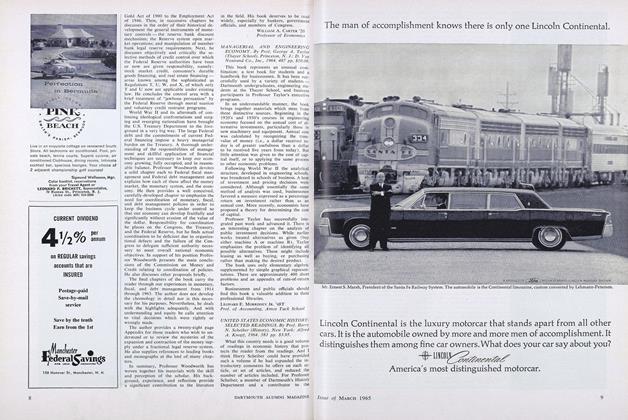

BooksMANAGERIAL AND ENGINEERING ECONOMY.

MARCH 1965 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY JR. '48T