The two adjectives chosen by the editor to characterize his father's correspondence - "strange" and "intimate" - are understatements of the first order. In the genre of posthumously published letters few volumes seem as "strange" as this one. Indeed, it is not a letter at all but more properly a diary; it comprised over 10,000 typewritten pages and had been written sporadically over a period of 30 years. After his father died in 1968 Page Smith inherited Ward Smith's voluminous manu- script packed in two trunks.

When Smith read his father's "letter," his "first impulse," he writes, "was to burn it." And well he might have! For it is clearly, as Smith recognizes, "a randomly obscene work in the form of a letter." Much of it is given over to recounting in explicit detail the father's sexual exploits, indeed debaucheries; it is a meticulously detailed scorecard of a sexual super-athlete with explicit names of most of the players and all the plays. "Intimate," the second adjective of the sub-title, seems the understatement of the year.

Even stranger, how does Professor Page Smith, one of our most eminent historians, biographer of John Adams, winner of the Bancroft Prize, professor of history at UCLA, and ex-chancellor of University of California, Santa Cruz, come to edit and publish what he himself characterizes as a "dirty book"? Smith is blind neither to the question nor to its implications, and in a moving foreword and afterword he records both his debate with himself and his motives in deciding to publish the book. His moral dilemma was made the more difficult because the profligate father had sired a "square" son - "something of a prude," he calls himself. A self-confessed "closet monogamist," he believes "in fidelity, in mastering one's passions rather than succumbing to them. . . . Virtually everything that my father did . . . seemed to me both wrong and personally and socially destructive, evil if you will."

Why then did he not follow his initial impulse to burn the letter? For two reasons: one professional, the other personal. In the obscene manuscript which the moralist found revolting the editor-historian detected some redeeming social virtue: "some historical-sociological-psychological significance." For during the rare times when Ward Smith was not well and thoroughly bedded he was a man of some significance: secretary to New York Governor Nathan Miller, a participant in the presidential campaigns of William Howard Taft and Herbert Hoover, friend of the famous in society, politics, and the arts. And amid the pornography" is embedded some of the stuff of social history, shrewd comments, analyses, and evaluations of important personages and events of the 1920s through the '40s. Secondly, on the personal level, the editor-son saw publication as an attempt at "reconcilement" between himself and his father, a chance "to perform some kind of expiation for him and for myself," to atone for the life-long estrangement between father

One may well disagree with the wisdom of the decision to publish, as this writer emphatically does; his father's memory would seem to have been better served by silence and by consignment of the manuscript to the flames at the outset. But it would be harsh indeed to fail to sympathize with the personal dilemma and the moral anguish of the editor-son or to call too closely into question the professional judgment of the historian-son.

A LETTER FROM MYFATHER: THE STRANGE, IN-TIMATE CORRESPONDENCEOF W. WARD SMITH TO HISSON PAGE SMITH. Page Smith'40, editor. Morrow, 1976. 472 pp.$12.50.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWORDS AND PICTURES MARRIED The Beginnings of DR.SEUSS

April 1976 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureStrangers in the House?

April 1976 By RAYMOND L.HALL -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

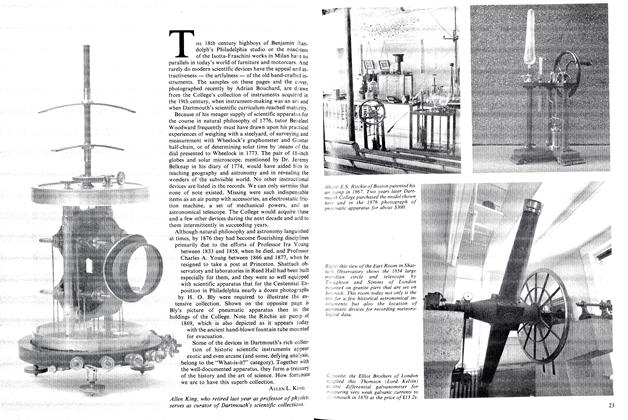

FeatureTHE 18th century highboys of Benjamin Randolph's

April 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

April 1976 By GILBERT F. PALMER IV, FREDERICK H. WADDELL -

Article

ArticleVox Clamantis et Clamantis; or College Bites Man

April 1976 By TERENCE R. PARKINSON '71

ROBERT H. ROSS '38

-

Books

BooksDRIFTWOOD: MAINE STORIES.

April 1974 By ROBERT H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksCredit to the Age

June 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFear of Flying, Combat in the Forecourt

October 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFundaments

June 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksPassable

DECEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksThe Alchemist

OCTOBER, 1908 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksDeaths

June 1948 -

BOOKS

BOOKSEditor’s Picks

MAY | JUNE 2019 -

Books

BooksPREGNANCY: THE BEST STATE OF THE UNION.

APRIL 1972 By JOHN W. SCHLEICHER '40, M.D. -

Books

BooksCASES AND MATERIALS ON FEDERAL TAXATION

April 1950 By LLOYD P. RICE -

Books

BooksOLD QUOTES AT HOME.

JANUARY 1968 By MAUDE FRENCH -

Books

BooksJoseph Hawley, Colonial Radical

DECEMBER 1931 By Robert E. Riegel