(An Iroquois Winter Sport)

Dartmouth is particularly fortunate in attracting duringeach college generation one or two Indian boys who carryon the original purpose of the College, that of educatingIndians and white boys side by side in the "liberal" fashionwhich was the boast of Eleazar Wheelock. Those of thealumni fortunate enough to attend football games last fallwhen the writer of this article sang various songs to variousstadii are already familiar with the Dartmouth freshmanwho is carrying on the Wheelock purpose. For a number ofreasons the editors are unable to furnish charts and diagrams of this sport described by Sundown, although hehimself sketched out a few "snake" models that mightserve for patterns. However, those who do not care to erect"snake" courts in their own backyard will find pleasure inthe naive narrative and the background of this sketch.

FROM early childhood I can remember some cold days in February when men came at short intervals into our well-constructed log-house to get a hot bowl of corn soup, a great delicacy among my people. Others came for pieces of hot mince pie or apple pie, thereby showing that they were developing a taste for the food of the white man. Mother and her maid (or whatever you choose to call the squaw who worked for us with a huge remuneration of seventy-five cents per week) were on their feet all day, waiting on those men, washing some of the dishes, sweeping out the snow which the men tracked in, and keeping the supply of food on hand. I spoke my language fairly well then and was also able to recognize English when I heard it spoken. Thus, I could notice that there were men of different tribes present,—thinking only in terms of tribes rather than nationalities, the white man consequently falling into that category. Briefly, some of them spoke a dialect which I had not heard before. All this had very little significance then. Besides, having been destined by some god to always be a liability, I was more concerned with eating corn soup indefinitely and always insisted on having the pieces of pork that added so much to the flavoring—and taste. The yelling outside, consequently meant nothing.

A few years later on a similar occasion, my big brother led me by my heavily-mittened hand one morning to the straight stretch of road in front of our house. On our way men paused to gaze on the affectionate brothers that we sometimes were. On nearing the road we heard excited men yelling to our left. They were lined up in a straight double row, facing each other and slightly bent over to facilitate closer scrutiny of something between them. Frantic waving of arms accompanied the yelling. My brother and I were not on the road but an instant when we realized that this surely was a gala occasion. There were many men there. Along the road was a trough in the snow, looking so straight and perfectly formed that it seemed to be made by some mechanical device. We stood near it. Far off to the right we saw men dressed in jerseys of various colors. Just then my brother called my attention to a man in the act of throwing something in the trough. A little speck appeared, growing as it came toward us. Now it was directly in front of us but only for a fraction of a second. It acted mad, as if it were caged and wanted to escape its bounds, this long shining shaft. Again the men to the left of us began yelling frantically as the shaft slowed down.

Only then did I begin to realize what was meant by a snowsnake, or a game of snow-snake.

THE SNAKE

As a matter of fact, there are several species of "snake." When there is a contest, the length has to be uniform, but the weight is left to the discretion of the contestant. To begin with, the material is usually of heavy wood. This is for greater momentum. The side which is destined to do most of the sliding is broadestprobably three-quarters of an inch or an inch at the middle. This gradually tapers to a point at the front end which is the head, but it narrows down at the opposite end or the tail to facilitate its being thrown from the end of the index finger. Besides being the broadest, this side is worked upon most to prevent all possible friction—it must be very smooth. The reverse side of the shaft is as difficult to shape as it is to explain. The thickest part is at the head. From there it tapers to a sharp point or nose. Reversely it quickly becomes much thinner and is thinnest at the end. The two other opposite sides are symmetrical, narrowing anteriorly to the nose point and exteriorly to a width convenient for the index finger.

When the smoothest surface possible is attained, the snake is finished with a coating of shellac. For perfection, however, the nose is often treated specially. Little grooves or canals are cut in the wood in such a manner as to permit some molten metal such as lead to fit into it securely and so that the very tip end may be metal. This is done because the snake has a bad habit of running head-on into trees and fence posts. Without this metal the point would soon become dull.

MUST BE POLISHED

To get the greatest satisfaction out of it, however, one must doctor it so that it will slide as easily as possible in snow or on the hard-bottomed trough. This doctoring, the physicist might appropriately compare with lubrication. The fans in winter sports might compare it to waxing of skis. At any rate it serves the purpose of cutting down friction and keeping the wood dry. Various mixtures of waxes, tallows, candles and animal fat are made and rubbed on the surface and polished until the surface shines. When there is a contest a man has the job of polishing, keeping busy with his pieces of flannel and waxes. There are different mixtures of "swagum" for varying conditions of snow—the brittle cold snow or the soft, melting snow, for instances. So very important are those compounds that an ordinary man may throw farther than a strong man if the "swagum" he uses is better, and the gambling is almost invariably between two men who have some secret mixture and who have hired strong athletes to throw their snakes for them.

With an outfit like the one already discussed one may have pleasant, healthful recreation. Either one can follow horse-drawn sleighs and use the sleigh tracks as troughs in which to throw, or one may, when the snow has hardened and formed a soft .crust, walk across big fields, throwing to his heart's content on top of the vast, white sheet. It is interesting in the latter case to watch the dark figure speeding across a huge expanse of white. A. neat, clear track follows in its wake.

MAKING A TROUGH

But when one speaks of snow-snaking seriously, more work is necessary if it is to exist in reality. The good workmanship of the trough has been referred to. This is the usual method of producing good results. A man with a steady gait, sharp eyesight, and patience volunteers or hires his services when a suitable place has been found. As the first three hundred yards must be very straight and smooth, this man chooses two points far ahead, he aligns himself with them and walks in that direction, always being sure that he is in the same straight line with them. Other men with steady feet may follow him so that they may tramp down the snow to a fairly hard bottom. After that a heavy squared log with rounded corners is dragged in the trench over and over. This leaves a fair surface. Sometimes, small humps or hollows are left on the bottom. If this is left as it is, the snake will jump out of the trough in the first place, probably hitting someone, or it will penetrate and enter the base or side of the trough in the second case. Consequently, more time is spent in cutting down the humps or filling in the hollows. Then the log is again dragged several times. Starting places are made near the extremities. Each contestant has to start from the same mark. The run-way must be firm and impenetrable to stamping or running feet. Finally, the two ends of the trough may be extended, not so carefully, perhaps, as the other part; for the snakes are not dangerously fast when they reach there.

They are thrown from both ends to insure fairness in case of a gradual decline or incline of the trough, for the slightest difference in slope can make a huge difference in showing the efficiency of the "swagum." Lack of memory forbids me to tell the distance to which the snakes are thrown; a quarter of a mile is a conservative estimate.

LIKE BOWLING

The throwing itself requires skill obtained by experience. Bowling, in general, resembles it somewhat. Much stress is given to this part of the game, for this is the time when the snake can jump out or penetrate its bounds most easily. The shaft must be in line with the trough and as near the same level with it when it is released. If not it will jump out or enter its walls. Besides, slamming it harder than necessary is a good means of wasting energy; and on soft, melting snow the man who does it might as well not compete, for he will only cause small grooves on the bottom of the trough, spoiling it for the other men.

For the sake of reminiscence, I might say that childish curiosity which prompts such innumerable questions with which we are all familiar made me wonder why those men were yelling so excitedly and why they yelled "go-la! go-la! go-la!" while the opponents yelled "ho! ho! ho!" (The go-la! turned out to be a vulgarism of "go long," while the "ho" is self-explanatory if one but thinks of jargon used in equitation.) The men yelling undoubtedly had what was to them heavy stakes on a special snake that came crawling slowly on the bottom of the trough, turning slowly from side to side on its stomach in such a life-like manner.

On speaking to an audience of friends of the Indians, a friend of mine was asked if the Indians were religious. He replied with a positive answer—that they wereadding in a naive way that if there were a religious meeting and a horse-race at the same time, the horserace would be more fully attended. As an analogy to that confession, I can state that the sounds of "go-la!" and "ho!" intermingled with the Sunday morning hymns and the service in general. Which group of people had more enthusiasm I should be very embarrassed to state. Neither can I tell whether the fans were excited because of stakes or because of innate enthusiasm. I will say that I cannot see how graft could have existed under the circumstance. Besides, we were not thoughtful enough of self-preservation to resort to such methods. There were no special judges to mark the distances. Anybody could perform the function, but pity the man who was seen cheating by the other Indians present, nine out of eight of whom would be blood-thirsty or could easily become as savage-like.

I have called snow-snaking an Iroquois winter sport because all tribes of that confederacy are familiar with the game, and those tribes have been known to compete against each other, healing the social breach that might exist between them.

R. B. SUNDOWN

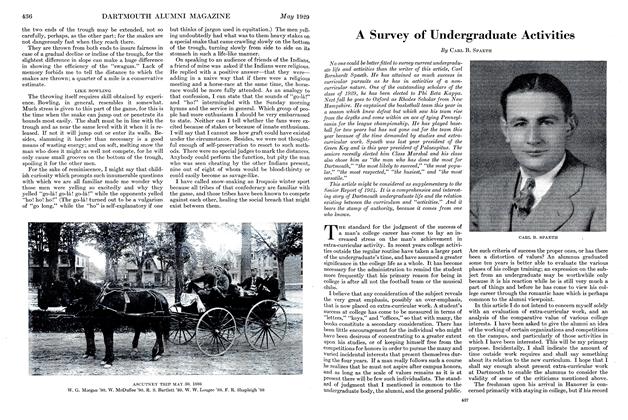

INDIAN SHINNY GAME The Crow Indians in Montana play the finals of their shinny game in June, and here is the whole field in action

OBSTACLES MEAN NOTHING The horses and carriages happened to get in the way of the players but nothing can stop the game

ASCUTNEY TRIP MAY 30, 1888 W. G. Morgan '90 W. McDuffee '90 R. S. Bartlett '89, W. W. Lougee '88, F. R. Shapleigh '88

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Survey of Undergraduate Activities

May 1929 By Carl B. Spaeth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1898

May 1929 By H. Phillip Patey -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1923

May 1929 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Life in 1835

May 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

May 1929 By Arthur P. Allen

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH NIGHT CELEBRATION

November 1920 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1960 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate

By CHARLES F. PIERCE JR. '58 -

Article

ArticleA Tribute tO W.F.T

April 1939 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS '01 -

Article

ArticleWomen of Dartmouth

MARCH 1997 By George Robinson -

Article

ArticleRELATED TO HARVARD REFUSAL

January 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40