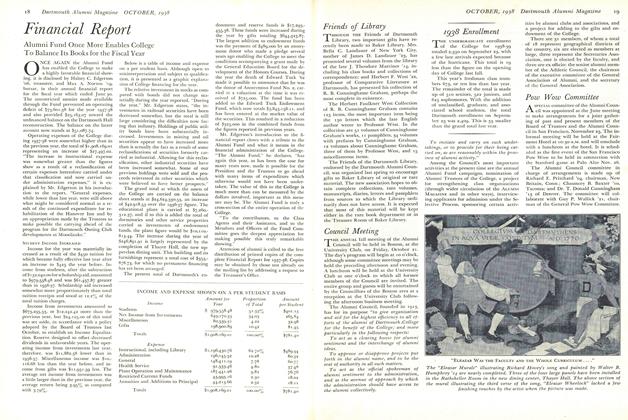

( A College Course for Alumni)

IT was a saying of the ancients that a man never opens a book without reaping some advantage from it. Authors of romances and novels, however, were not so long since considered polluters if not public poisoners. A grave moralist of the age of Louis XIV wrote that "a scribbler of novels and a stage-poet, being superlative corrupters of souls, should be regarded by decent folk as guilty of an infinity of spiritual homicides." Likewise, one theologian declared that the Devil inspired the French translation of the Spanish romance, "Amadis de Gaule," in order to help along the revolt of Luther, and later, even Goldsmith felt that romances in which the ruling passion was love were instruments of debauchery. That the novel was much later considered worthy of anathema is proven by the following words of a parish librarian to a boy reader: "I am going to give you a book of Jules Verne, but if it were a novel I would not give it to you."

To-day, the novel, so long condemned that it was totally neglected by the legislators of Parnassus, as a medium, has so dominated the literary field that it is conscripted for presenting biography and even history.

A novel has been defined with subtlety as the "metaphysics of. intelligence." For our purposes, the French novel or romance is fiction in prose or verse and treats of love. The English novel of adventure excludes love as clearly as a tragedy of Corneille excludes cuckolded husbands. A good novelist is a person who tells stories in a superior way, such as Balzac who said: "Hearing these good folk, I lived their lives, I felt their ragged clothes on my back, their desires, their needs passed into my soul." Or Dostoievsky, who seeing of a Sunday, a workman walking without his wife at his side, but accompanied by a little boy, forms in his imagination a complete drama. Unlike the historian, the writer of fiction creates his events and his characters. The result is that the reader grieves that Old Goriot is not loved by his unfeeling daughters, that Madame Bovary sinks lower and lower, without realizing that, were it otherwise, neither Balzac nor Flaubert could have produced their masterpieces.

As an introduction to the first semester course in the French novel, the student reads "Trimalchio's Dinner" of Petronius and the Golden Ass of Apuleius, the only extant examples of truly Latin fiction. The first work is a prose-verse account of the vices of society in Nero's time. Its crass realism is thoroughly modern in tone. The second book should be read if only for the first literary appearance of the delightful story of Cupid and Psyche. The episode of the slave attached to a fig tree and consumed by ants is one of the realistic gems of this satirical, fantastic romance.

SONG OF ROLAND SHOWS FEUDAL LIFE

Coming to French literature the warlike and religious national epic, the Song of Roland, gives a good picture of feudal life in the 11th century. It is one of the few "songs of deeds" of the period that could not be sacrificed without great loss to literature.

No excursion through French romances would be complete without the delightfully told Aucassin and Nicolette, so well translated into English by Andrew Lang. The escape of the hero from the tower, the Hell episode and that of the peasant who lost his ox, and the burlesque account of King Torelore in child-bed ("I'm a mother") are unusually good.

In spite of its handicap of allegory, the 13th centuryRomance of the Rose, thanks to its style and keen observation, was one of the very few works which survived the shipwreck of medieval literature. Lasting or ephemeral sentiments like Jealousy, Fear, Courtesy and Hypocrisy are personified and help or hinder the efforts of the lover to pluck the rose, symbol of the beloved one. The 18,000 verses of the second part are characterized by a systematic disparagement of women. It is curious that the Church did not object to the extraordinary dissemination of a work which violently attacked the celibacy of the clergy, which declared princes to have received their power from the people, and which preached obedience only to the laws of Nature and Reason with a scepticism characteristic of Rabelais, Montaigne, Moliere and Voltaire.

Recent essays on Rabelais by Anatole France, Samuel Putnam and Alfred Nock show the popularity of this much misrepresented Franciscan friar and doctor of medicine. Like the immortal "Don Quixote," Rabelais's "Gargantua and Pantagruel," a prodigious parody of medieval romances, is perhaps a novel against novels. Written for the cultured few, the average student without the aid of an instructor is as unlikely to extract its "substantific marrow" as is a juvenile to understand the idea of Voltaire's Candide.

D'Urfe's 'Astree" (1610) inspired by the pastoral romances of Spain and Italy amused the generations wearied by the civil and religious wars of the 16th century. In this romance the shepherdess Astree banishes the unfaithful shepherd Celadon from her presence. Considerable magic, 5,000 pages, and a tangled skein of some thirty-five plots and sub-plots, novels in themselves, are required to bring Hymen upon the lovers at the end.

The prodigious vogue of the Astree unfortunately spawned such idealistic pseudo-historical argosies as the 2,000,000 word "Grand Cyrus" and the ten-tomed "Clelie" of Mile, de Scudery. The famous geographical love-map, called the "Carte du Tendre," has saved this romance from literary oblivion. Map in hand, the amorous heroes of Rome, the Brutuses and the Lucretias, propose the solution of enigmas and delicate questions of gallantry.

Moliere's comedy, the "Precieuses Ridicules" (1659) and the epoch-making masterpiece in the novel of the 17th century, "La Princesse de Cleves," destroyed the taste for long romances a la Scudery. Madame de Lafayette's short work is the first important psycholog- ical novel in French literature. In a concise and swiftly moving intrigue, a married woman's heart is analyzed with modern penetration. Like a tragedy of Corneille, its theme is the conflict of love and duty.

"The Letters of a Portuguese Nun" (1669) are the actual letters of a nun who fell in love with a French nobleman serving with the army in Portugal. They enjoyed a tremendous success in their day. Pathetically sincere, their theme is disappointed love.

FAIRY TALES WITH UNHAPPY ENDINGS

Among writers of fairy tales none attained the conciseness and exquisite charm of Charles Perrault who published his "Mother Goose Stories" in 1697. The sophisticated here find Little Red Riding Hood with the unadulterated zmhappy ending, Cinderella and Blue-Beard, all told with fantasy and delicate touches of realism.

Fenelon's "Telemachus" (1699), says a writer in Diderot's Encyclopedia, is the most beautiful novel in the world. In poetic prose of great beauty, the author narrates the search of the hero for his father Ulysses. The ever and over-moralizing guide Mentor saves his pupil from the wiles of the nymph Calypso. Hustled away in the nick of time, the young man helps a king reform his city, fights many battles, visits Hades in quest of his father, and finally is married to the homeloving Antiope.

Lesage's "Gil Bias" (1715) is almost a world classic. Packed with the misadventures which befall the hero, this picaresque narrative is a general survey of French society from king to commoner. A "Human Comedy" before Balzac, its genuine realism and naiVe, humorous style explain its universal appeal.

Marivaux, better known for his comedies, in his two unfinished novels shows progress over Lesage in character delineation. In "Marianne," the heroine, a little minx of an orphan is drawn with such clinical mastery that the reader comes to appreciate the definition of "marivaudage" as the art of saying not only everything you intended to say and did but also everything you intended to say and didn't.

The Abbe Prevost's "Manon Lescaut" is too well known to require comment. The opera and even the cinema have consecrated Des Grieux's lava-like passion for the perfidious yet charming Manon. The first great lover in the French novel leads directly to such sombre heroes as Goethe's Werther, Rousseau's Saint Preux and Chateaubriand's introspective Rene.

If modern fiction owes much to Prevost, it was the "Nouvelle Heloise (1761) of Rousseau which finally gave the long despised novel its standing as a semirespectable literary genre. Rousseau took Samuel Richardson's mammoth epistolary novels as a model. Gifted however with the power of condensation, with Saint Preux's first letter to Heloise, revealing his love, his situation and his scruples, Rousseau gets as far along as does Richardson in the first three volumes of "Clarissa Harlowe." The chief tendencies of Jean Jacques's masterpiece, which contains the philosophical and social ideas of its author, are realism, sentimental analysis, and moralizing.

No course in French fiction can neglect the genial and inimitable master of the philosophical tale. Voltaire's "Candide" should be read and compared with Johnson's "Rasselas." It is one of the few narratives that will bring increased pleasure with successive yearlyreadings. Diderot's "Nun" and "Rameau's Nephew" complete the list of readings required of students of the 18th-century novel.

The few great novels which have come down to posterity proclaim the novel as one of the most exacting forms of literary activity. Surely a fitting device on the shield of the novel would be these words of Saint Augustine: "In the fire, gold glitters and straw smokes."

Note. The second semester (French 26) is devoted largely to the works of Chateaubriand, Stendhal, Balzac, Merimee, Zola, and Anatole France.

Chateaubriand's exotic "Atala" with its American setting offers profitable comparison with "Green Mansions," the even more exotic masterpiece of W. H. Hudson.

Flaubert's "Madame Bovary" is the unmistakable prototype of Sinclair Lewis's "Main Street" and, with the Russian novelist Gontcharov's "Oblomov," completes an international trilogy which gives a remarkable picture of bourgeois mediocrity.

Partial List of Books Used in French 25. 1. The Satyricon of Petronius (Modern Library edition) 2. The Golden Ass of Apuleius (Modern Library) 3. Chretien de Troyes: Erec at Enide (Paris, Boccard, 1924) 4. Les Quinze Joies de Mariage (ditto 1929) 5. Rabelais: Gargantua and Pantagruel (Modern Library) 6. La Princesse de Cleves (Nelson) 7. Voltaire's "Candide" (Tallandier) 8. Rousseau's "La Nouvelle Heloi'se" (Mellottee) 9. Diderot's "Le Neveu de Rameau" (Payot) 10. Prevost's "Manon Lescaut" (Tallandier)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe New Tuck School Plant

December 1930 By Dean William R. Gray -

Article

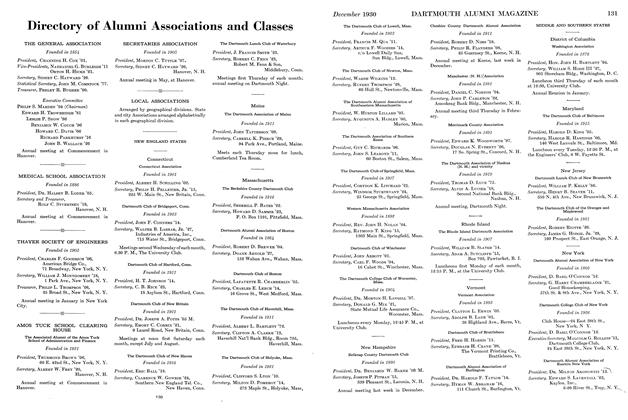

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

December 1930 -

Article

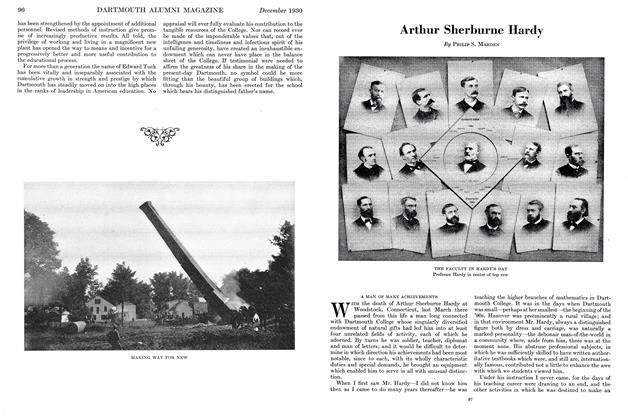

ArticleArthur Sherburne Hardy

December 1930 By Philip S. Marden -

Article

ArticleHarry Hillman: A Dartmouth Institution

December 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Lettter from the Editor

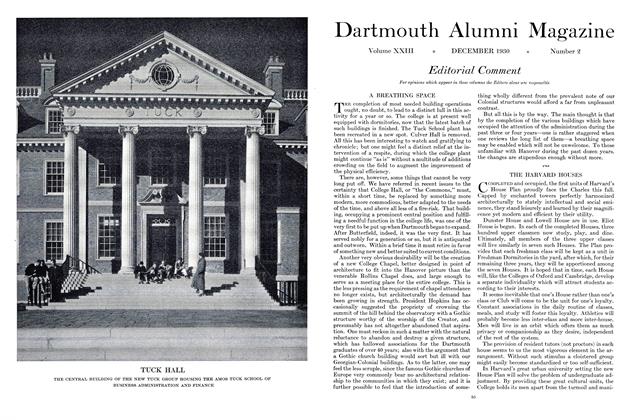

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

December 1930 By Truman T. Metzel