For opinions which, appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

ANOTHER YEAR BEGINS

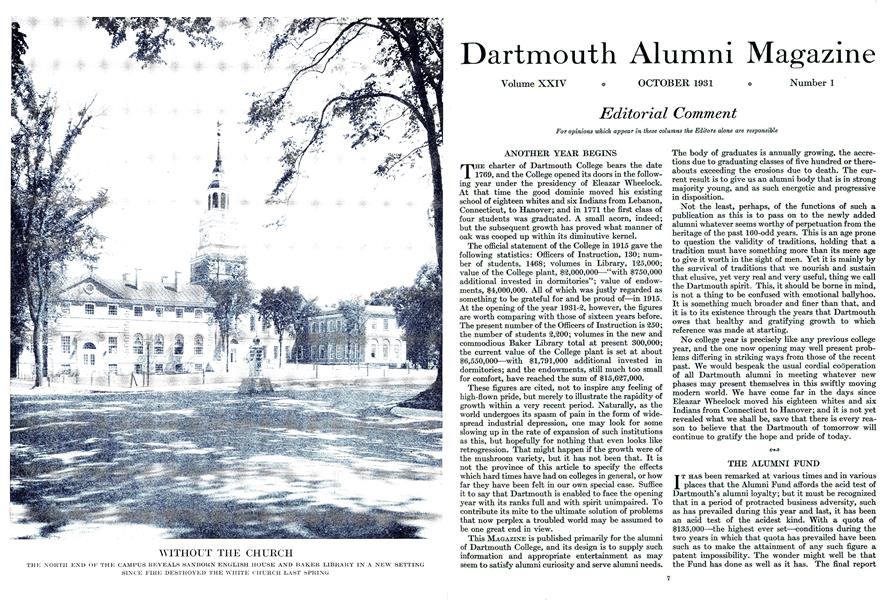

THE charter of Dartmouth College bears the date 1769, and the College opened its doors in the following year under the presidency of Eleazar Wheelock. At that time the good dominie moved his existing school of eighteen whites and six Indians from Lebanon, Connecticut, to Hanover; and in 1771 the first class of four students was graduated. A small acorn, indeed; but the subsequent growth has proved what manner of oak was cooped up within its diminutive kernel.

The official statement of the College in 1915 gave the following statistics: Officers of Instruction, 130; number of students, 1468; volumes in Library, 125,000; value of the College plant, $2,000,000—"with $750,000 additional invested in dormitories"; value of endowments, $4,000,000. All of which was justly regarded as something to be grateful for and be proud of—in 1915. At the opening of the year 1931-2, however, the figures are worth comparing with those of sixteen years before. The present number of the Officers of Instruction is 250; the number of students 2,200; volumes in the new and commodious Baker Library total at present 300,000; the current value of the College plant is set at about $6,550,000—with $1,791,000 additional invested in dormitories; and the endowments, still much too small for comfort, have reached the sum of $15,627,000.

These figures are cited, not to inspire any feeling of high-flown pride, but merely to illustrate the rapidity of growth within a very recent period. Naturally, as the world undergoes its spasm of pain in the form of widespread industrial depression, one may look for some slowing up in the rate of expansion of such institutions as this, but hopefully for nothing that even looks like retrogression. That might happen if the growth were of the mushroom variety, but it has not been that. It is not the province of this article to specify the effects which hard times have had on colleges in general, or how far they have been felt in our own special case. Suffice it to say that Dartmouth is enabled to face the opening year with its ranks full and with spirit unimpaired. To contribute its mite to the ultimate solution of problems that now perplex a troubled world may be assumed to be one great end in view.

This MAGAZINE is published primarily for the alumni of Dartmouth College, and its design is to supply such information and appropriate entertainment as may seem to satisfy alumni curiosity and serve alumni needs.

The body of graduates is annually growing, the accretions due to graduating classes of five hundred or thereabouts exceeding the erosions due to death. The current result is to give us an alumni body that is in strong majority young, and as such energetic and progressive in disposition.

Not the least, perhaps, of the functions of such a publication as this is to pass on to the newly added alumni whatever seems worthy of perpetuation from the heritage of the past 160-odd years. This is an age prone to question the validity of traditions, holding that a tradition must have something more than its mere age to give it worth in the sight of men. Yet it is mainly by the survival of traditions that we nourish and sustain that elusive, yet very real and very useful, thing we call the Dartmouth spirit. This, it should be borne in mind, is not a thing to be confused with emotional ballyhoo. It is something much broader and finer than that, and it is to its existence through the years that Dartmouth owes that healthy and gratifying growth to which reference was made at starting.

No college year is precisely like any previous college year, and the one now opening may well present problems differing in striking ways from those of the recent past. We would bespeak the usual cordial cooperation of all Dartmouth alumni in meeting whatever new phases may present themselves in this swiftly moving modern world. We have come far in the days since Eleazar Wheelock moved his eighteen whites and six Indians from Connecticut to Hanover; and it is not yet revealed what we shall be, save that there is every reason to believe that the Dartmouth of tomorrow will continue to gratify the hope and pride of today.

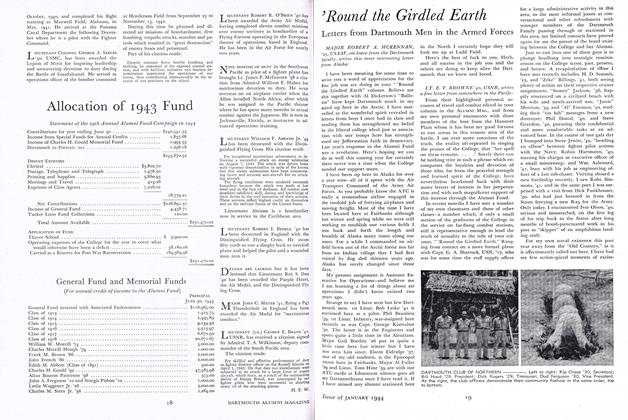

THE ALUMNI FUND

IT HAS been remarked at various times and in various places that the Alumni Fund affords the acid test of Dartmouth's alumni loyalty; but it must be recognized that in a period of protracted business adversity, such as has prevailed during this year and last, it has been an acid test of the acidest kind. With a quota of $135,000-the highest ever set—conditions during the two years in which that quota has prevailed have been such as to make the attainment of any such figure a patent impossibility. The wonder might well be that the Fund has done as well as it has. The final report reveals that a total of $109,195.01 was received from 5,315 contributors.

The handicaps are many and obvious. The general tightening of the financial pinch was bad enough a year ago, but worse this year because the tendency to cut dividends has spread more broadly, producing a lessened income for investors. A less manifest handicap became evident to the Fund managers as the campaign wore on, in the fact that many who had been generous givers before appeared to be reluctant to figure as curtailing their customary contributions, as if it would be better to give nothing at all than to give less than before— a deplorable conclusion and one which every effort was made to counteract. One of the great sources of pride in this Fund record has been the percentage of contributors; and the desirable thing was to maintain that record at about its usual height, even if the per capita contribution must infallibly shrink under the pressure of untoward conditions.

The task for Fund committees at the moment, and until the situation shall improve, seems to be the education of the alumni to realize that every little helps, and that if a man who has usually given $100 or $50 finds it impossible to give more than $25 or $10, it is far better for the welfare of the Fund to give that than to give nothing. For some years the committees have striven to make it felt that every gift is appreciated, irrespective of its smallness or greatness, so long as it represents an honest effort of the giver to do what he reasonably can and helps to bring our participation as close to the 100 per cent as is humanly possible. The feeling that if a man could give no more than a dollar or two he might as well give nothing is one against which a long succession of Fund directors have had to contend. This year it had also to contend against the feeling that curtailment of a formerly larger gift was in the same category.

WHAT TO DO?

HAVING won through to a degree as Bachelor of Arts, the young graduate emerging from the shelter of the college cloisters faces the necessity in most cases of finding "something to do." It seems a difficult time for such, in that the world is passing through a protracted stage of business depression in wyhich jobs cannot be regarded as even normally plentiful. One feels even more than the usual sympathy, in consequence, for the army of young men now turned loose upon a world which has already a colossal army of unemployed, especially for such as hold the not at all unnatural belief that the work one should undertake ought appropriately to be that for which a college training fits one. Why spend four years in study, if one is to take any sort of paid job that offers and that could be done, perhaps, by a young man who had never even finished the High school course? In conditions such as obtain at the moment in this country and nearly everywhere else, it may be the duty of the graduate to embrace any sort of opportunity to earn his bread and to praise Allah for the chance; but it is bound to irk the man who sees in this a subordination of higher to lower things—a setting of mere bread-winning against "a career," to the latter's prejudice, and a permanent or temporary negation of the idea that spending four years in college is worth one's while.

This may be fallacious, however. The object of a college education is not entirely, and not even primarily, to fit the recipient to earn his living, but rather to fit him to live with profit to himself and others in the world of men, and to enjoy intelligently his living when he has earned it. The college girl who has specialized in history and whose aim is to turn this learning to account in teaching, or in assisting the diplomatic service, may feel a natural reluctance toward the acceptance of a humble position as telephone switchboard operator in an electric light office, with the incidental duty of being "nice" to customers who come in with complaints; for this isn't the sort of job to which her studies have been leading her, and taking it means abandoning ambitions, in favor of a distinctly welcome and immediate $20 a week. What is one to do? Ordinarily one would wait patiently for an opening more consonant with one's training and designs. But hard times may make that either impossible or unwise. Is the four year course, then, to be regarded as frittered away? Against that it may be desirable to register a protest.

One trouble with the present tendency of American youth to seek collegiate education in such enormous numbers is that it creates a demand for what are sometimes called "white-collar jobs" that greatly exceeds the supply thereof. That the bulk of college graduates become bond salesmen is a favorite topic with the jokesmiths of the land—and it has just enough truth behind it to be disquieting. The necessity for squaring the college education with the activities of after life may well account for the tendency, so deplored by Mr. Flexner, to include curious items in the curriculum and to make such count toward a baccalaureate degree, so that where once an A.B. meant that its holder had studied Greek, Latin, Philosophy and other purely cultural subjects, it has come to mean that the possessor has qualified in cookery, bed-making, stenography, typewriting, landscape architecture and the Lord knows what-not. Possibly the only answer is to go back to the purely cultural and treat a liberal education as merely fitting its seekers for the proper enjoyment of a living, which may be earned in any way you please.

COLLEGIATE BLUE RIBBONS

WHEN a university in Oklahoma not long ago offered to make Will Rogers a Doctor of the Humanities, or some such thing, that preeminent wise-cracker not only refused but inquired to know what the university thought it wras trying to do. Was it intent on making the honorary degree business ridiculous, or what? Since then the newspapers have indicated that a similar distinction was offered by some other college to a woman writer whose specialty was advice to the lovelorn in a syndicated feature, and that in her case either a smaller bump of self-abnegation, or a belief that the award was worthily bestowed, led to the gratified acceptance of the degree. Opinions are bound to differ as to this, as to most other questions; but it has long been apparent that there was need to curb with a resolute hand the propensity to hand out academic honors to all and sundry.

Would a degree for Will Rogers tend to discredit the custom of making such awards as seriously as Mr. Rogers modestly supposes? Probably not. He has become an international celebrity, and his acute observations on the follies and foibles of his time, while couched in the vernacular, are as acute as were those which a generation ago were made by "Mr. Dooley," the saloon keeper of Archey Road. Mr. Rogers's homely witticisms are to be read in the most ponderous and pretentious of our leading journals. He is a philosopher—no less. And yet one has the uneasy feeling that Mr. Rogers was more nearly right than the university which sought to do him honor concerning the fitness of the method chosen. In any case his modesty does him credit and might be emulated by several hundred every June when the colleges proffer their intellectual blue ribbons, too often to recipients whose merits from the purely academic and intellectual point of view are sadly to seek. One thinks of such as primarily intended to recognize the most altitudinous sort of intellectual attainment; and Mr. Rogers felt the incongruity of offering an academic degree to one whose metier is monolog wisdom to the accompaniment of a swinging lariat. The incongruity was more apparent than real, for as has been said Mr. Rogers is essentially a philosopher. None the less it was there.

In the United States, there being no patent of nobility to bestow, and no "birthday honors list" to fill with names that everybody knows, our college degrees given "honoris causa" may seem a sort of equivalent. It is true that Great Britain regularly makes knights and baronets of her actors, musicians and steamer captains, so that a professional humorist would seem by no means to be barred from the charmed circle. Still there's a subtle difference between having the king tap a worthy subject on the shoulder with the flat of the monarchical sword, and having the president of a university bestow a Latin degree on one whose profession is to purvey wise-cracks for the multitude in colloquial speech.

Fewer and better honorary degree selections would seem to be in order if the distinction is to be kept in the category of coveted possessions to which a man may aspire. Therein Mr. Rogers is right, even if perhaps excessively modest concerning himself. We doubt that the specialist in advice to the lovesick would qualify under a rigidly exacting standard. The wealthy benefactor who gives a new laboratory is sometimes frowned upon by the purists when he is made an LL.D.; but after all he has performed a real service for academic learning. The successful generals and admirals, often the recipients of such honors, form a more dubious class. No one cavils at the singling out of preeminent scientists and inventors, in this mechanical age, for purposes of decoration. And yet it is true enough that out of the average Commencement list there are usually not more than two or three names to the dozen that bring the hearer to his feet with a genuine cheer, prompted by the knowledge that in those cases at least there is "not the shadow of doubt—no possible doubt whatever."

VOLUME TWENTY FOUR

THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE enters its twenty-fourth year with this the first issue of the new volume. Copies of the October number are being sent to more than 11,000 alumni as a sample of what may be expected during the coming eight months. All who receive the MAGAZINE in this way are being urged to subscribe at the nominal yearly fee.

Credit may well be given to the business management of Dartmouth's graduate publication. Not many years ago an annual deficit seemed to be the inevitable result of publication. The steady rise of subscription lists to the point where more than 5,000 alumni are receiving the MAGAZINE regularly is largely responsible for the present balance sheet which, it is true, shows no considerable profit, but which nevertheless shows no loss.

The editors are ambitious to improve the MAGAZINE with each issue. Innovations are planned and await only sufficient finances to be carried out. The possibility of paying valued contributors for their writing, once out of the question, now seems possible if subscriptions and advertising can be increased over figures of previous years.

The ALUMNI MAGAZINE is devoted to the interests of Dartmouth alumni. Previous readers are assured that its quality will be maintained at the same high standard as in other years. Its subject matter and composition will be made more attractive as time goes on. Comment or suggestions are welcomed by the editors. It is a magazine for the alumni. We want it to be by the alumni.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe College as a Cooperative Enterprise

October 1931 By Ernest Martub Hopkins -

Article

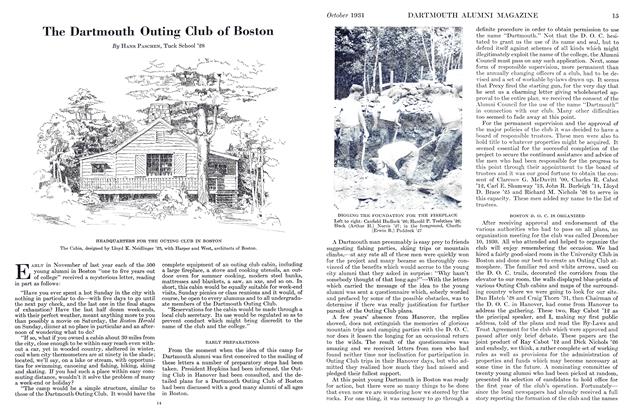

ArticleThe Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston

October 1931 By Hans Paschen, Tuck School '28 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

October 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1911

October 1931 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1905

October 1931 By Arthur E. McClary

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

January, 1926 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

January 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

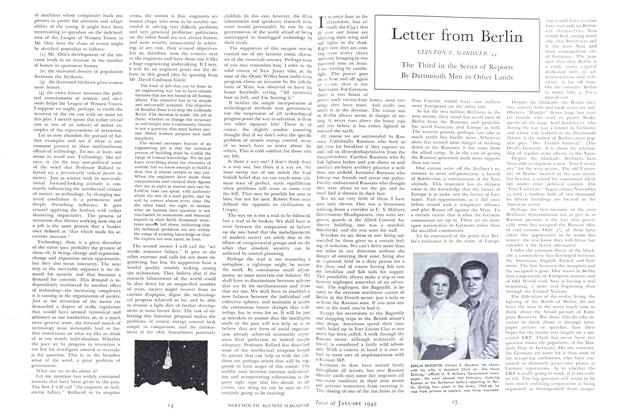

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Berlin

January 1949 By CLINTON C. GARDNER '44 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Geneva

May 1949 By MICHAEL J. DE SHERBININ '42