DARTMOUTH is a liberal college. A liberal college is in its nature a civic foundation devoted to the promotion of intelligence. Intelligence is under- standing and understanding is the beginning of wisdom.

The liberal college of today is not primarily interested in fitting a man for any trade and is not essentially concerned with what profession shall be his. Its major solicitude is for what a man shall be and it has only minor concern with what he shall do. Herein the liberal college of contemporary times is a pioneer and assumes a burden greater than ever before. It has deliberately foregone the easily understood and readily effective motivation which actuated many of the colleges in their early days when their original purpose was to fit for the Christian ministry,—a purpose which later expanded to fitting men or other professions. As compared with the concreteness and definiteness of such a program, and the quicker response which its tangibility could secure from the student body, the liberal college of today undertakes a difficult role when it bases its philosophy on a motivation directed towards giving men right attitudes towards life and appreciative points of view concerning it. More than ever before the college must look to its student body for understanding of its purpose and commitment to it if the college effort is to be rewarded with effective accomplishment of its purpose.

Perhaps if we divorce the word relativity from its technical associations in science and philosophy, it signifies best that with which the college has essential concern,—the ability to see life as a whole with its component parts in relationship to one another and the ability to gain comprehension of life through knowledge as a whole. It is with such assumption that the liberal college fails to be impressed with attacks upon it, either that it stands aloof from life and is therefore impractical or that it imposes an unjustifiable delay in men's getting to the specialized work of their chosen careers.

In regard to the latter of these criticisms, it may be asserted that four years is not an inordinate space of time to spend, if therein foundations are laid on which for the succeeding half century life can be built higher and broader and more abundantly than otherwise would be the case. Concerning the charge that the liberal college holds aloof from participation in life, the reply of the college is that it does, and that if possible it would do so more completely. It is the most practical thing that it does. The liberal college is concerned with the problem of stationing its men where they will secure true viewpoints of life as a preliminary to their participating actively in contemporary affairs. Its insistence must be on an initial intellectual detachment from the world's immediate activities and from the spirit of the immediate period while analysis is made of their relationships to achievements and failures of the past and to possibilities of the future. This is not to say that in lofty contemplation we are to forego consideration of the present or that we are to forget that the college period is simply a respite in time for preparation for becoming constructive citizens of the world, capable of acceptance of life's responsibilities and of possessing ourselves of life's satisfactions. It is to say that for the man willing to make himself receptive to college influence and to make intelligent use of his opportunity in an observation-post so well placed for studying life's formations, because apart from them, completer understanding may be had of himself and of life about him during the succeeding years when he shall be so surrounded by a wall of immediate demands upon interest and strength that for the time perspective cannot be his.

If some still argue, as some will, that this conception of the college is visionary and impractical, attention may be given to the practice of the most astute of pennantwinning baseball managers whose policy is to keep highly paid newcomers to his team on the bench beside Viim analyzing the play for their first season in the major league. Again recollection may be had of the statement of a renowned football coach that the greater his hopes in regard to a football candidate, the more he tried to refrain from using him in games during his sophomore season, so that by studying intercollegiate contests rather than playing in them he could have the greater ultimate value to the team. For the sake of making this point entirely plain, it might be added that sitting on the bench without attention to the details of play or spending the sophomore fall in idle reverie without any concentration on strategy of the game would do nothing except to defeat a man's ambitions at these specific points. Even here cooperation is indispensable for achievement.

The march of events is so rapid in our time that the experience of one day may be little like that of the next. The impress upon one generation's mind of the events of its time are certain to give an attitude towards life different from that which will be given to another generation by a different combination of events. To a large majority of our population the melancholy period of the World War seems but a little while ago. Nevertheless among the greater number enrolled in the undergraduate body it is scarcely remembered at all, while some of these men entering college were not born at the outbreak of the War. Even in the space of a year the formations of life's procession undergo a transformation. College openings, annually recurring, thus are set against backgrounds of human interest which vary widely from one autumn to another. However much alike these may appear superficially, the public temper which dominates one differs greatly from that which defines the spirit of the next.

In place of extended comment upon world conditions at the present time, I submit a story which is told by Dr. L. P. Jacks, recently retired from the principalship of Manchester College in Oxford:

A genial Irishman, cutting peat in the wilds of Connemara, was once asked by a pedestrian Englishman to direct him on his way to Letterfrack. With the wonted enthusiasm of his race, the Irishman flung himself into the problem, and taking the wayfarer to the top of a hill commanding a wide prospect of bogs, lakes, and mountains, proceeded to give him, with more eloquence than precision, a copious account of the route to be taken. He then concluded as follows: "'T is the devil's own country, sorr, to find our way in. If it was meself that was going to Letterfrack, faith, I wouldn't start from here."

Two years ago at the time of the opening of college buoyancy and optimism ruled. The impetus of widespread prosperity had bred speculation as to whether long-accepted economic laws were really existent and whether ever again the American people need suffer the misery and want of financial depressions such as the past had known. Now dark pessimism reigns, confidence has been lost, and the question is even more definitely raised whether ever again the skies can brighten. The vital realization that mankind needs today is that life is never static and that a myopic mental eye is never capable of more than partial or blurred sight. It is only by the acquisition of knowledge and the comprehension of its import that vision can be gained. And it is as true today as when the Book of Proverbs was written that where there is no vision the people perish. By such considerations we may arrive at conclusions, justified by some degree of logic, in regard to what the real function of education is and what may be its benefits to mankind.

The importance of the college in the field of learning is not that of an agency through which, exclusively, education may be acquired. Its social significance is rather that to it has been so largely delegated by public confidence and public esteem the responsibility for making itself the conservator of educational method and the authority to speak in definition of what education is and how it may be acquired. Argument can be made plausibly, and to some it seems convincingly, that the college is potentially one of the most enduring foundations established by man, contributing as it does to understanding of the spiritual, social, and political life of mankind. The distinction accorded to the college by the faith of men demands quality in the service which it renders. It behooves the college to make so plain that he who runs may read, the difference between brains and intelligence; pedantry and scholarship; intellectualism and wisdom; casual information and knowledge; sporadic facts and truth; and many other distinctions of like kind.

Too few men are becoming intelligent among those enrolled in educational institutions. It is a compara- tively simple thing for a person to develop brain power, but it is difficult business to develop the essential blend of knowledge, purpose, and sense of proportion which constitutes intelligence. Mental lucubrations have the same relationship to mind that gymnastics do to the body. A physically attractive body may be an aesthetic delight, but it soon palls unless representative of a real personality. An intellectually brilliant mind may win admiration from minds less sparkling in action or less furnished with diverse gifts, but unless it is accompanied by constructive purpose it comes soon to be recognized as a mere show piece. These things the college must make plain.

The minute, however, that we begin to discuss the potentialities of the college there enters into our reckoning an algebraic X, an unknown quantity representative of the disposition of the student body to make the college purpose vital in spirit as well as definite in form. No conception of the college can be held to be true which does not consider it as a cooperative enterprise between the instruction corps and the student body. Conceivably the enterprise might be highly successful with a student body so fired by a zest for learning that it would profitably utilize the facilities and tools made available to them even though a faculty should not be fully competent. But it is inconceivable that an institution could be long held in high respect in which the student body should be indifferent or antagonistic to utilizing the opportunity which the college offers even with recognition accorded to the high rank of the faculty. Let us examine some of the characteristics which make certain undergraduates uncooperative in the effort to realize the college purpose.

First, there is the man of passive type whose ideal of life is an effortless existence. His mental processes are so dormant that lack of learning does not embarrass him and the many agreeable avocations in college life fill his days with contentment. He personifies the philosophy of Giordano Bruno's statement that ignorance is the most delightful science in the world because it is acquired without labor and without pains and it keeps the mind from melancholy. We all know men of this kind. Equipped with a store of opinions appropri ated from books or friends and a choice selection of verbal formulas they become adept at putting on a pro- tective coloring which to the casual acquaintance makes them indistinguishable from men of learning.

Then there is the resistant type made up of men who assert that they know what they know and who are not going to endanger their souls or their social orders or their political affiliations by allowing themselves any sympathetic consideration of other men's conclusions on these subjects, however much such conclusions may be based on long years of careful investigation or on wide experience.

Likewise there is the man of inflated ego who confuses his greater mental agility as compared with his fellows with mental superiority and by gradual process, of which he himself is largely unconscious, expands his self-sufficiency until he holds that in all the world there is no one entitled to advise, guide, or direct him, to say nothing of restraining him.

Far more agreeable in personal and official relationships, but nevertheless subversive of the ability of the college to fulfill its desirable destiny, is the man who looks upon the educational advantages of the college as something to which he must submit himself in sufficient degree to give him access to the privileges of college community life. Or the man who, in analogy to the epitaph which described a woman as having died as the result of spreading herself too thin, incurs the hazard of becoming intellectually moribund by frittering away his time on a multitude of pleasant but inconsequential things.

In moments of attempted self-justification for accepting, or perhaps condoning, a practice which allows the educational pace of which the college is capable to be slowed down by undergraduates of these various types, I reflect that men of purposeful intelligence will find their accomplishments retarded throughout their lives by the necessity of working in association with men of these characteristics and so that perhaps there may be some educational advantage in getting used to it early.

Aside from all this, moreover, the college has labored increasingly in recent years against the effects of unintelligent espousal by undergraduates of certain con- tentions which the colleges themselves originally advanced and which have essential merit if properly un- derstood and if accepted with due qualifications. Prominent among these are the arguments that formal edu- cation should be inspirational rather than disciplinary and that the method of the educational process is solely for training men to think to the exclusion of giving them instruction.

Analogies are sometimes misleading but likewise they are frequently suggestive. The football player who slights his training per.'od and enters upon the scrimmage session without having fully conditioned himself frequently finds himself incapacitated for going farther. No instinctive flair for the sport and no susceptibility to the inspiration of playing the game can offset the injuries resulting from tendons and joints whose strength has not been built up to stand the rigors of the physical contacts of competition. The laws governing preparation for the scrimmages of life can be taken no more lightly. The college cannot accept as determinative of its policy the vague impressions of undergraduates that an altruistic desire to be helpful to their fellowmen should be accepted as an equivalent to mastery of the laws of social control; or that a sincere aspiration for self-expression in writing should be accepted in lieu of learning by study and practice what constitutes good usage in English; or that an idealistic ambition to enter upon a political career neutralizes the need for a painstaking and rigorous study of the history of the state and of the development of legal procedures.

Similarly the college disputes the argument that education s solely concerned with developing the capacity to think and has nothing to do with receiving instruction. The first essential of thought is that there shall be something to think about. The more complete the knowledge in regard to the given subject the more productive the thinking is likely to be. It is perfectly true that some of the axioms of today are likely to be fallacies of tomorrow and that some of what seemed to be knowledge yesterday is revealed as error today. Nevertheless, there is no reason to believe that man's mental capacity has not been as great for centuries in the past as it is today. For us to start our thinking on life's problems de novo without acquaintanceship with what men have thought in the past and why they have held their beliefs would in all probability bequeath the realm of thought to future generations cluttered with fallacies equal in number if not identical in kind to those which past ages have inherited.

Life is a blend of the art of being and of the science of doing. For the man who wishes his life to contribute some satisfaction to himself and to have some significance to his fellows it is of supreme importance that he have some comprehension of the factors which have in the past reduced men from vibrant being to mere existence and which have made their efforts futile or harm- ful. The great leaders in the sphere of preventive medicine in their struggle to give health to the world have to know as much about disease as about well-being. It is a mistaken notion that education is concerned simply with great human achievements and with the avenues of approach to what we hold to be truth. There is profit as well in knowing why men and causes have failed and why individuals and generations have missed the highways which lead to truth.

Such knowledge cannot be evolved solely from one's inner consciousness. Neither can the sources of information be found without great waste of time and effort except under instruction. Compared with the difficulties of building a college faculty of men rigorously trained, competent in their respective fields, genuinely consecrated to the search for truth, and generous in their willingness to guide others to the heights they have climbed, it would be a simple matter to recruit an instruction corps possessed simply of pleasing personalities, a smattering of knowledge, and an infectious enthusiasm for education. But without the ability in such a group to define what learning is and where it may be found, the undergraduate would be without the major value available to him which now attaches to his college course. An indispensable preliminary to learning to think is the acceptance of guidance from competent instruction as to where the world's store of knowledge is and how it may be drawn upon.

There is in consideration of this matter a further point to be made, seldom elaborated in these days, concerning the deep personal satisfaction and the intellectual exhilaration of contact with those of greater knowledge than ourselves. Ruskin has stated this clearly in his chapter on "The Pleasures of Learning." He says, "And of these pleasures, necessarily, the leading one was that of Learning, in the sense of receiving instruction; —a pleasure totally separate from that of finding out things for yourself,—and an extremely sweet and sacred pleasure, when you know how to seek it, and receive."

In short, all experience in the field of higher education verifies two points made by Professor Pitkin in his recently published volume on "The Art of Learning"; that every new subject requires its own background of previous learning; and that every advance to such a new study must be made with intense interest. Herein is epitomized the essential cooperation from the undergraduate which is indispensable for the college aspiring to be of major importance. There must be, on the one hand, a faculty qualified by training, by knowledge, and by spirit to transmit and to expound the learning acquired through past ages. There must be, on the other hand, a student body free from self-sufficiency and specious sophistication, willing to cultivate and demonstrate interest in and enthusiasm for that which constitutes learning.

More and more I tend to the belief that the college requires too much and expects too little. I should like to see the time come when the quantity of work requisite for a degree would be reduced but when the quality would be enhanced. Such modification of current practice must wait however until a student body is ready to give convincing assurance of its understanding of the value of time and opportunity which are offered to it in college life as nowhere else in life. So long as the probability exists that lessened requirements would effect a diminished concentration on .the main purpose of the college, a more complete immersion in the distractions of college life, a more frenzied hysteria for social diversions, and a depleted, if not forgotten, sense of the obligations of discipleship to learning,—so long, requirements must be held, if not increased. Herein college policy must await a cooperation in the student body that it has never submitted evidence of being willing to give. At the same time I but bespeak the attitude of all men in official position in the college in saying that there is nothing which detracts more from joy in their work than the necessity of enforcing requirements or of imposing discipline.

The whole problem of making the college a more effective agency for public service and a more vital contributor to the personal satisfactions of its individual students waits upon a cooperation more complete on the part of the undergraduate body to realize the college ideal. In conversation this summer a keenly observant and discriminatingly friendly graduate of the college said that undergraduates of today seemed to him more personable, more mentally alert, and more serious than was true of student bodies a few decades ago but that they were characterized, in comparison with the men of his time, by the vital defect of an unwillingness to assume or to accept responsibility. I agreed with him. On reflection, nevertheless, it seems to me that the condition is not necessarily an enduring one. It is folly to suppose that college men of this era have less capacity for responsibility than men of any former time. It must therefore be that they lack the will.

Extenuation may be urged that this is but a reflection in youth of the spirit of their elders who in abandoning commitments to old allegiances have assumed no obligation to establish new ones. Loyalties to family, to church, to political party, to state and to the fundamental principles of law have been thrown into the discard until authority wanes at all points and the social controls are constantly weakened. It may be that the old working hypothesis by which human society held together was faulty but it was far better than none. It is no mere rhetorical phrase to say that civilization is threatened. The forces of disruption gain momentum steadily. It is still less an empty phrase to say that if the advantages of civilization are lost it will be the youth of today who are the principal losers. "For everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under heaven," said the Preacher, who continued, "a time to break down and a time to build up."

The wrecking crews have done a fairly complete job in the last decade with structures which had long served society and with foundations on which belief had long stood. The time has come for the builders. The world looks for the rise of a new generation of constructive genius, intelligent as to conditions that are needful and willing to assume responsibility for creating these. It will come. Shall it be yours?

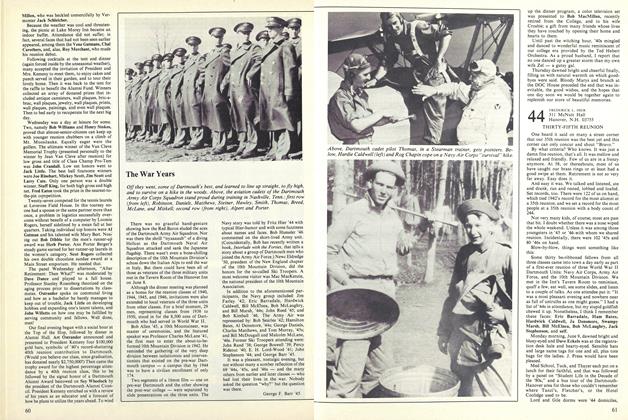

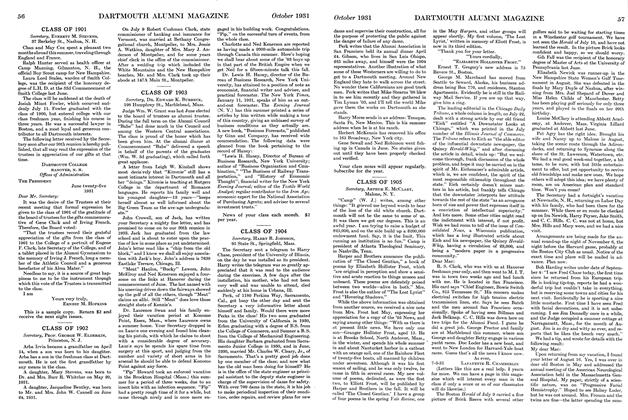

THEY ALL WANT TO LAY THE CORNERSTONE(Weight: 800-1000 pounds)Left to right: Charlie Paddock '27; Tom Herlihy Jr '26; SamDennis '28; Henry Whitmore Jr. '26; Jock Davis '27; Canfield Hadlock '26; Huck Norris '27; George Davis '38; HaroldTrefethen '26 and Greenough Abbe '24.

T'HE exercises opening Dartmouth''s163 rd year were held in Webster Hall,Thursday, September 17. President Hopkinsdelivered the address here reprinted, "TheCollege as a Cooperative Enterprise." Hisopening paragraph is a challenge to the careful eading and study of the annual convocation address. Epigrammatically he says"Intelligence is understanding and understanding is the beginning of wisdom." ThePresident calls for a "cooperation morecomplete on the part of the undergraduatebody to realize the college ideal" in order tosolve the problem of "making the college amore effective agency for public service anda more vital contributor to the personal satisfactions of its individual students

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston

October 1931 By Hans Paschen, Tuck School '28 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

October 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1911

October 1931 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1905

October 1931 By Arthur E. McClary