THE ADDRESS of President Hopkins to the newly matriculated class on the occasion of each reopening of the College has come to be recognized as one of the most important—probably the very most important administrative utterance of the year. That of the current autumn was no exception, though perhaps less notable for its quotable epigrams than some in other years have been. It was what such an address naturally ought to be—a direct statement to newcomers to Dartmouth of what the College conceives to be the reasons for their coming, and of what it regards as the real object of their remaining for four years under tutelage.

The best way to deal with such a talk to young men entering upon a new and unfamiliar field is naturally to listen to it, or to read it in its entirety. Attempts to summarize are bound to impair it. One may say, however, that the President sought to clarify the conception of what a liberal college should strive to accomplish, and above all to stress the primary necessity of cordial and ready cooperation on the part of those who form its undergraduate body. The liberal college is concerned with what a man is to be, rather than with what he is to do. It is laying the foundations; and it insists that time spent on making them both broad and deep is time not wasted, although it may not possess the showy character of a superstructure. Rushing too hurriedly to the construction of the latter might be productive of more impressive results, but a jerry-built man is as likely to crumble as a jerry-built apartment. If insistence on the provision of foundations and backgrounds delays the advent of the man into some chosen profession, let it do so. Time will prove it to have been worth the doing, though four years be devoted to it. The ensuing half century will in all probability be the better for this.

That the liberal college withdraws a man temporarily from the active participations of life is true and it is done deliberately, for the sake of a better perspective. One may not enjoy the viewpoint of a separate star, of course; but a certain remoteness from the hurly-burly may enable a youth to obtain a completer understanding of the life about him, for use in his succeeding years.

The college is anxious to fit a man to think but it by no means follows that it is not likewise charged with some duty to instruct concerning what has been thought already and before. After all, what we most desire is to raise the general level of intelligence; and intelligence is "a blend of knowledge, purpose and a sense of proportion," rather than mere brain-power undirected and on the loose. True intelligence is brain-power disciplined to usefulness; but certainly not fettered.

If one looks for outstanding epigrams, they are not far to seek. "Life is a blend of the art of being, and the science of doing." There is something useful in the knowledge and understanding of our predecessors' failures in the quest of truth. At least we know where truth is not, and may look for it in more promising quarters. Again, "More and more I tend to the belief that the college requires too much and expects too little"—perhaps the most provocative sentence in the whole address, and the truest. "I should like to see the time," says the President, "when the quantity of work requisite for a degree would be reduced, but when the quality would be enhanced. Such modification of current practice must wait however until a student body is ready to give convincing assurance of its understanding of the value of time and opportunity which are offered to it in college life as nowhere else in life. So long as the probability exists that lessened requirements would effect a diminished concentration on the main purpose of the college, a more complete immersion in the distractions of college life, a more frenzied hysteria for social diversions, and a depleted, if not forgotten, sense of the obligations of a discipleship to learning, so long, requirements must be held, if not increased. Herein college policy must await a cooperation in the student body that it has never submitted evidence of being willing to give." In fine, if the college is to reach tolerable ideals of perfection the student body must help thereto.

Above all, this generation must accept responsibility for the future constructively. Nothing is easier than to tear down the antiquated work of older time, which has served its day but will serve no longer. Mistaken though it was, it actually did serve and was far better than nothing. If it be done away, something must take the place of old allegiances lest what we call civilization be rent asunder and chaos supervene. "The time has come for the builders," now that the wreckers have done their work. The ground has been cleared. And the young men entering college today are of the generation which must do the building for well or ill. To face responsibility squarely and accept its burdens is not easy, and to do it requires that the man who does it be fit. We have had our day with the snappy young critics, who have indeed found out wherein much was wrong; but that does not help us to the substitution of what is right, in the room of what we have discarded. "The time has come for the builders," as it has come so often before and always by the wisdom of Providence the builders have appeared. They will again, no doubt; and not a few, as in older times, will have been trained in the liberal colleges of the land.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

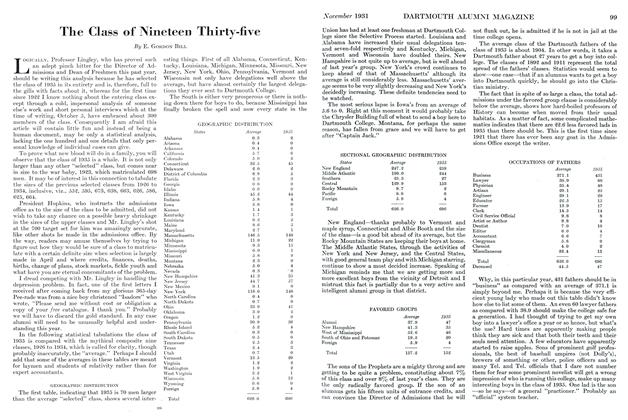

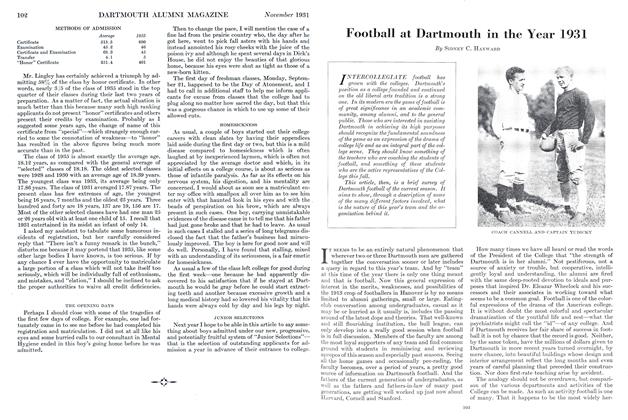

ArticleThe Class of Nineteen Thirty-five

November 1931 By E. Gordon Bill -

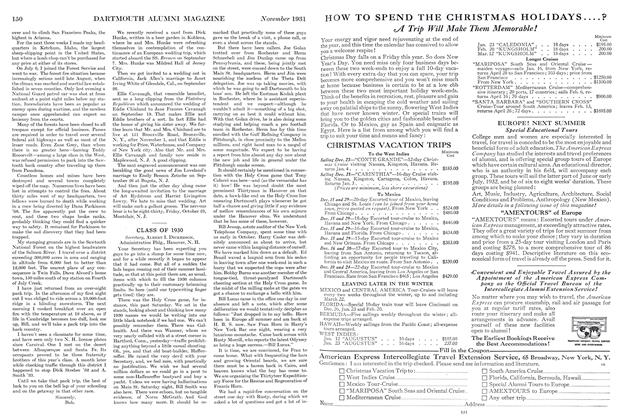

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth in the Year 1931

November 1931 By Sidney C. Hayward -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

November 1931 By "Hap' Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

November 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1926

November 1931 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1929

November 1931 By Frederick William Andres