The carefree quality of my sophomore summer was altered when The D reported that Christopher Reed, a well- liked professor of biology, had been diagnosed with bone cancer. Since none of his relatives proved to be a compatible match for a life-saving bone marrow donation, hundreds of students came forward to have their blood tested. Yet neither my blood nor the blood of other students was configured in exactly the right way to permit transplant. A nationwide donor search also failed, and Professor Reed died the next year at age 45.

It was, I thought, the end of the story. But a few years later I got a phone call: "This is the National Bone Marrow Registry. You appear to be a possible bone marrow match for a one-year-old boy who has chronic leukemia." Would I be willing, the voice in Newjersey asked, to come in for further tests to see if I was a close enough match?

I was a match. I agreed to the operation.

The bone marrow registry attempted preemptive damage-control for my emotions. They emphasized how extremely rare it is to find a marrow match outside the family—and rarer still for the recipient to survive. Thus they would not release any information about the recipient, other than his sex and age, until a year after the operation.

But the registry encouraged me to send a letter to my recipient. I was able to tell him and his family, whoever and wherever they were, how much I admired their courage. I told them that during the past several weeks I had put as many positive and life-filled thoughts as I could into this fluid that was sitting in my bones. And I tried to tell them how desperately I wanted their little boy to grow old happily.

A year later Karen Rumensky told me that she had read this letter as she sat in a darkened hospital room in Philadelphia watching the pink marrow drip steadily and silently down a tube directly into her son Michael's tiny chest. And then I heard a little "hello" on the other end of the phone as the two-year-old who now shared my blood type and allergies shyly succumbed to his mother's coaxing. He was beating the odds.

Now Michael lives the life of many five-year-old boys, trying to copy his brother's skill in sports, looking forward to trips to the bowling alley, hugging most people he comes in contact with.

And when he hugs me, I rea lize a biological connection to him that is stronger than any connection I will ever have to another human being. His blood -and my blood are exactly the same. His mother insists there is something more. When she hears Michael sing and sees him play ball, she is convinced that my interests were somehow transmitted with my marrow.

Technically speaking, she can't be right. But then I never would have guessed that my life would become so entwined with the life of a family three states away.

I never would have guessed that a professor's death would eventually save a life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

October 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

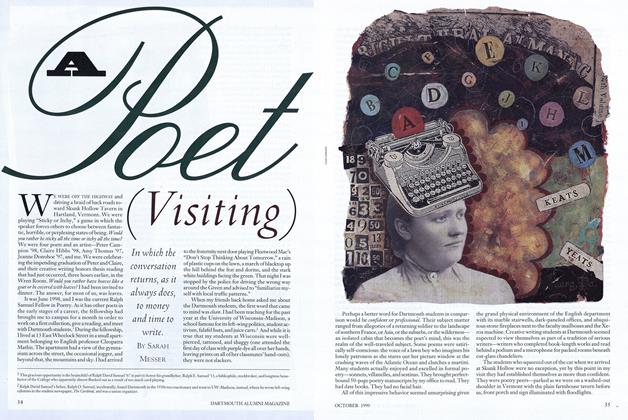

FeatureA Poet (Visiting)

October 1999 By Sarah Messer -

Feature

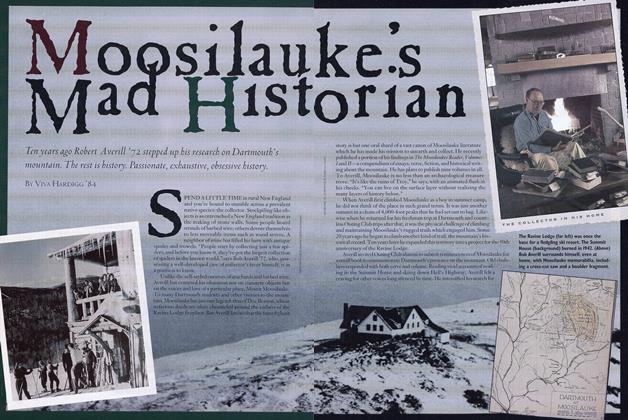

FeatureMoosilauke's Mad Historian

October 1999 By Viva Hardigg '84 -

Article

ArticleStories on Rye

October 1999 By Tamar Schreihman '90 -

Article

ArticleTeamwork

October 1999 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

October 1999 By Noel Perrin