THAT zealous seeker after truth, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, is still hot on the trail of abuses in college athletics in Bulletin No. 26, released for publication June 15. The topic is "Current Developments in American College Sport" and the subject matter follows lines already laid down in previous bulletins. Summarization in such cases is difficult, but it may be said that on the whole the atmosphere is reported to be just a little clearer. It is recognized that the future of college athletics is more important than its past. "The deflation of American football has begun." One discerns that a return to a more sincere appreciation of the true values of sports and sportsmanship is under way, despite the gross exploitations of sensation-mongering sporting writers in the public press, and despite the occasional instance of an alumnus whose one idea is to hunt up good athletic material and see that it goes to his own college, with generous, if unrevealed, financial support. "The road at times seems long," concludes the report, "but the American college will not weary in well-doing." In other words, the evils are sensibly diminishing but have still a long way to go.

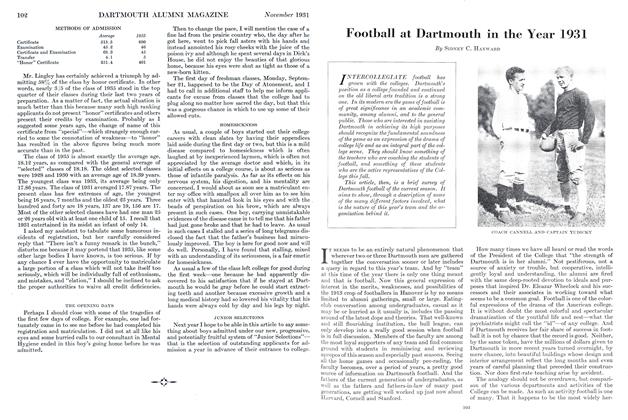

Football is the point to which most attention is devoted, and a highly interesting assertion is made when the report points out a decline in the gate receipts during the recent season. Thirteen rather inconsiderable colleges did record an increase; but 25 (including all the major institutions) showed a falling off in the season's revenues derived from games. To the casual eye there may have seemed to be little difference in the special crowds in Stadium and Bowl, but the boxoffice seems to have shown a decrease in the cash-money. Reasons assigned are no less interesting. One college president thinks the prices of tickets have been set too high. The economic depression naturally has something to do with it. The fact that one may sit comfortably in a warm home and listen to the radio announcer is probably accountable for some part of the alleged decline. One also reads that the colleges have permitted such contests to become public shows and the fickle public is tiring of them. The undergraduates themselves are growing weary. They do not go to "pep meetings" nor do they go in as of yore for organized cheering. They react unfavorably to "set-up" games early in the season. They no longer look with scorn on the students who

For opinions which a-ppear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

actually prefer some other form of enjoyment, or even study, to attendance upon games. They are "sick of unsportsmanlike substitutions" during play. "Covert professionalism has alienated their sympathy." In fine, the undergraduate is setting a pace for alumni—and one sometimes suspects even for a few of the faculties and trustees to follow! In some colleges he is reported as favoring the abolition of "football holidays" decreed for the purpose of letting everybody forget about education for a week-end and make peerade to some adjacent metropolis to see the game without impairing the allowance of cuts. The report sagely opines that this improved attitude "may be only temporary," and notes no diminution of the zeal to tear down old stadiums in order to build greater. Still, it is offered for what it may be worth.

With the attitude of undergraduates toward intercollegiate sports this Magazine has no concern. It seems probable that intelligent young men really have been reacting against the excesses which we all know have marked the intercollegiate games in recent years. A salutary provision of nature often leads a disease to cure itself, if one will only allow it to do so. The more immediate concern is with alumni attitudes. One section of the current Carnegie report indicates a fear that alumni may abuse the invitation to consider themselves still an integral part of the college with "a voice" in the institutional policies; and it adds an expression of wonder whether or not the authorities who have "rather eagerly, in times past" granted such powers to the alumni fully understood what they were doing. But it is elsewhere admitted that the really offensive alumni in any college are few numerically, although they make more noise and exert more influence on the unthinking than they should. The alumnus with too lenient standards for athletic measurements and a propensity for interference with college athletics is called "the penalty one pays for graduating men without an education."

There is room for the belief that the evils still attending on college sport are in major part due to alumni interest, and that alumni might do much to minimis them. After all, such things as big football games are the only points of contact which large numbers of graduates have in later years with their colleges. Such contacts are not in themselves evil, but they too easily lead to evils. The thing to guard against is the temptation that doth so easily beset us as the result of our interest in the one thing in the year that brings the college home to us the temptation to talk about football as if we felt it were all the college existed for, and the desire to recruit the teams by inducing promising athletes to seek our own college, rather than another. The colleges are doing what they can to curtail the ravages of secretive professionalism, but the most effective remedy of all must always be in the alumni themselves. Dartmouth has been among the most insistent on the duty of alumni to avoid furtive professionalism, and it is our belief that this insistence has had effect. At all events one finds no condemnation attaching to Dartmouth in the latest of the Carnegie bulletins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

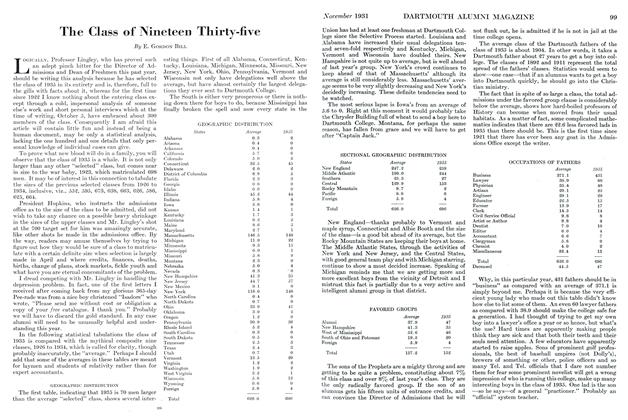

ArticleThe Class of Nineteen Thirty-five

November 1931 By E. Gordon Bill -

Sports

SportsFootball at Dartmouth in the Year 1931

November 1931 By Sidney C. Hayward -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

November 1931 By "Hap' Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

November 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1926

November 1931 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1929

November 1931 By Frederick William Andres