(Running Running Down the Missing Link)

I HAVE often been asked : What makes you go traipsing around all over the world whenever you get a chance? What are you looking for and what good will it do you or anyone else if you manage to find it? Such questions are not easily answered, and the answer if any, must be made in personal terms. The roots of the matter go back, some forty-five years, to when I became a "lifer," that is, to the time when I was caught by an eye, a stern judicial eye, and condemned to life long labor in a labyrinth of problems from which there was no way of escape except through the solution of one major problem. In my case, a very common one in the annals of science, my condemnation was not due to any fault or virtue of my own. I really did not mean to do it. But the judge was inexorable. It was like this. I happened to be playing around with the curious little eye in the middle of the head of such animals as spiders, horseshoe crabs, and scorpions, when I discovered that it arose from the roof of a hollow, or semi-hollow brain, in the same peculiar way as the middle eye in the head of man and other vertebrate animals. Ha-ha! Perhaps some animals like the scorpions are the long sought ancestors of the back-boned animals. But that was absurd! Who ever heard of such a thing? Everyone who knows anything about it is convinced that certain kinds of worms are the only animals worthy of that distinction. Besides no scorpion looks anything like a fish or any other vertebrate. So all my friends laughed and made good natured fun of me, for that is the way good friends usually treat their erring brothers. But there is a big kick in a laugh. It is a stimulant that often helps more than it hurts. So I began to play around a little harder and soon found out many other ways in which these two great types of life, under a heavy mask of superficial differences, are essentially alike.

Damitall, I said to myself, I'll show these biological fundamentalists a few things they don't know and something they never thought of before. That youthful attitude is not considered quite respectable in the best scientific circles, but it reveals a very powerful motive in all scientific work. And back of that is a still stronger and more permanent motive, or the desire to find out something that will satisfy our own nagging curiosity.

But of course the scorpions of today could not be the ancestors of the vertebrate stock. It must have been some kind of scorpions, if any, that lived and flourished many hundred million years ago, before the vertebrates themselves arose. And sure enough, there they were, duely stamped in stony records as the so called giant sea scorpions, which in every essential respect fulfilled this particular theoretical requirement. For untold millions of years they had been the highest animals of any kind in existence. In them the most important organs of the vertebrates had already attained a high stage of evolution, and they were arranged in a very peculiar pattern, much like that in all the back boned animals. All that looked very promising.

Moreover, living at that time with the giant sea scorpions there was a strange class of animals called ostracoderms, also of very great antiquity. They looked something like the sea scorpions on the one hand and on the other like true fishes, but in reality being neither one nor the other. The ostracoderms might well be the descendants of the sea scorpions and the ancestors of the vertebrates, and thus unite the upper and lower portions of the animal kingdom into one continuous and intelligible whole. If so, that would be the key to our labyrinth. It would open the door to the solution of countless problems of great importance to the biologist. But unfortunately forty years ago, very little was known about the ostracoderms, and the most fantastic notions concerning them were prevalent. The whole class, a very large and diversified one, became extinct hundreds of million years ago. Only a few fragmentary remains were preserved in the great museums of the world, and those had been obtained, from time to time, largely by accidents. Those specimens were rightly regarded as too precious to be touched with a chisel or any other instruments that might, perhaps, uncover some unknown structure, or perhaps injure them beyond repair. So after a futile study of the ostracoderms in all the great museums, in England, Scotland, Germany, Russia and America, there was nothing to do but to start out with the rather forlorn chance of finding better ones for myself, ones that I could play with in any way I pleased. And so began a long series of excursions to those parts of the world that, for one reason or another, looked most promising; to Canada, Newfoundland, Scotland, Spitsbergen, Russia, Australia, Java and Central America. Here again fortune occasionally favored and encouraged me. In Canada, in the cliffs on the north east side of the Bay of Chaleur, after seven or eight summer seasons of exploration, we finally discovered a rich deposit of ostracoderms, together with many primitive fishes, that were in an extraordinary state of preservation, so that for the first time the external anatomy of one kind of ostracoderm, Bothriolepis, could be worked out in great detail. This collection, now on exhibition in the basement of the new science building, is by far the best of its kind in existence.

But there still remained much to be done on other kinds of ostracoderms before we and our justifiably sceptical friends could be satisfied.

THE GREAT HIGHWAY OF EVOLUTION

The problem was greatly complicated by the fact that the transition from one type to the other was probably due to several correlated adjustments which temporarily revolutionized the visual, respiratory, and nutritive functions.

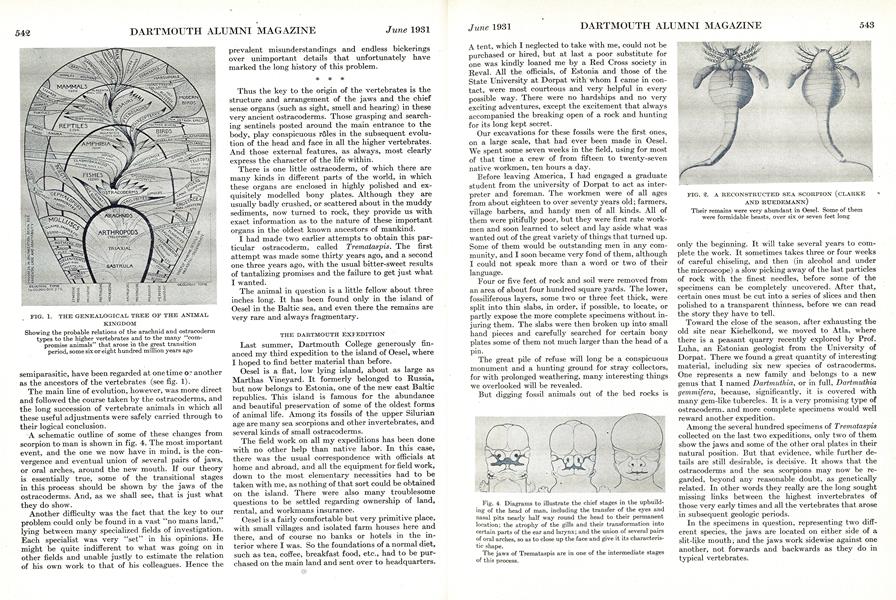

They were: (1) the final inclusion of the embryonic lateral eyes within the forebrain chamber; (2) the opening of the gill pockets into the alimentary canal; (3) the closing of the old invertebrate mouth and the opening of a new one on the opposite side of the head, and (4) the union of several pairs of jaw-like arches around the new mouth. But all these changes were of great functional value and finally they worked their own way out of an obvious functional impasse. During this long revolutionary period (comparable with the necessary adjustments in an overgrown household), many kinds of "compromise animals" arose, livable, but badly adjusted to the new conditions of life. Everyone of these types, many of them degenerate, sessile, or semiparasitic, have been regarded at onetime or another as the ancestors of the vertebrates (see fig. 1).

The main line of evolution, however, was more direct and followed the course taken by the ostracoderms, and the long succession of vertebrate animals in which all these useful adjustments were safely carried through to their logical conclusion.

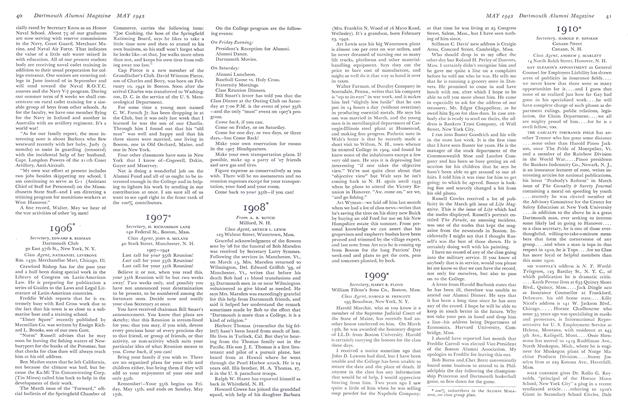

A schematic outline of some of these changes from scorpion to man is shown in fig. 4. The most important event, and the one we now have in mind, is the convergence and eventual union of several pairs of jaws, or oral arches, around the new mouth. If our theory is essentially true, some of the transitional stages in this process should be shown by the jaws of the ostracoderms. And, as we shall see, that is just what they do show.

Another difficulty was the fact that the key to our problem could only be found in a vast no mans land, lying between many specialized fields of investigation. Each specialist was very "set" in his opinions. He might be quite indifferent to what was going on in other fields and unable justly to estimate the relation of his own work to that of his colleagues. Hence the prevalent misunderstandings and endless bickerings over unimportant details that unfortunately have marked the long history of this problem.

Thus the key to the origin of the vertebrates is the structure and arrangement of the jaws and the chief sense organs (such as sight, smell and hearing) in these very ancient ostracoderms. Those grasping and searching sentinels posted around the main entrance to the body, play conspicuous r6les in the subsequent evolution of the head and face in all the higher vertebrates. And those external features, as always, most clearly express the character of the life within.

There is one little ostracoderm, of which there are many kinds in different parts of the world, in which these organs are enclosed in highly polished and exquisitely modelled bony plates. Although they are usually badly crushed, or scattered about in the muddy sediments, now turned to rock, they provide us with exact information as to the nature of these important organs in the oldest known ancestors of mankind.

I had made two earlier attempts to obtain this particular ostracoderm, called Tremataspis. The first attempt was made some thirty years ago, and a second one three years ago, with the usual bitter-sweet results of tantalizing promises and the failure to get just what I wanted.

The animal in question is a little fellow about three inches long. It has been found only in the island of Oesel in the Baltic sea, and even there the remains are very rare and always fragmentary.

THE DARTMOUTH EXPEDITION

Last summer, Dartmouth College generously financed my third expedition to the island of Oesel, where I hoped to find better material than before.

Oesel is a flat, low lying island, about as large as Marthas Vineyard. It formerly belonged to Russia, but now belongs to Estonia, one of the new east Baltic republics. This island is famous for the abundance and beautiful preservation of some of the oldest forms of animal life. Among its fossils of the upper Silurian age are many sea scorpions and other invertebrates, and several kinds of small ostracoderms.

The field work on all my expeditions has been done with no other help than native labor. In this case, there was the usual correspondence with officials at home and abroad, and all the equipment for field work, down to the most elementary necessities had to be taken with me, as nothing of that sort could be obtained on the island. There were also many troublesome questions to be settled regarding ownership of land, rental, and workmans insurance.

Oesel is a fairly comfortable but very primitive place, with small villages and isolated farm houses here and there, and of course no banks or hotels in the interior where I was. So the foundations of a normal diet, such as tea, coffee, breakfast food, etc., had to be purchased on the main land and sent over to headquarters. A tent, which I neglected to take with me, could not be purchased or hired, but at last a poor substitute for one was kindly loaned me by a Red Cross society in Reval. All the officials, of Estonia and those of the State University at Dorpat with whom I came in contact, were most courteous and very helpful in every possible way. There were no hardships and no very exciting adventures, except the excitement that always accompanied the breaking open of a rock and hunting for its long kept secret.

Our excavations for these fossils were the first ones, on a large scale, that had ever been made in Oesel. We spent some seven weeks in the field, using for most of that time a crew of from fifteen to twenty-seven native workmen, ten hours a day.

Before leaving America, I had engaged a graduate student from the university of Dorpat to act as interpreter and foreman. The workmen were of all ages from about eighteen to over seventy years old; farmers, village barbers, and handy men of all kinds. All of them were pitifully poor, but they were first rate workmen and soon learned to select and lay aside what was wanted out of the great variety of things that turned up. Some of them would be outstanding men in any community, and I soon became very fond of them, although I could not speak more than a word or two of their language.

Four or five feet of rock and soil were removed from an area of about four hundred square yards. The lower, fossiliferous layers, some two or three feet thick, were split into thin slabs, in order, if possible, to locate, or partly expose the more complete specimens without injuring them. The slabs were then broken up into small hand pieces and carefully searched for certain bony plates some of them not much larger than the head of a pin.

The great pile of refuse will long be a conspicuous monument and a hunting ground for stray collectors, for with prolonged weathering, many interesting things we overlooked will be revealed.

But digging fossil animals out of the bed rocks is only the beginning. It will take several years to complete the work. It sometimes takes three or four weeks of careful chiseling, and then (in alcohol and under the microscope) a slow picking away of the last particles of rock with the finest needles, before some of the specimens can be completely uncovered. After that, certain ones must be cut into a series of slices and then polished to a transparent thinness, before we can read the story they have to tell.

Toward the close of the season, after exhausting the old site near Kiehelkond, we moved to Atla, where there is a peasant quarry recently explored by Prof. Luha, an Estonian geologist from the University of Dorpat. There we found a great quantity of interesting material, including six new species of ostracoderms. One represents a new family and belongs to a new genus that I named Dartmuthia, or in full, Dartmuthiagemmifera, because, significantly, it is covered with many gem-like tubercles. It is a very promising type of ostracoderm, and more complete specimens would well reward another expedition.

Among the several hundred specimens of Tremataspis collected on the last two expeditions, only two of them show the jaws and some of the other oral plates in their natural position. But that evidence, while further details are still desirable, is decisive. It shows that the ostracoderms and the sea scorpions may now be regarded, beyond any reasonable doubt, as genetically related. In other words they really are the long sought missing links between the highest invertebrates of those very early times and all the vertebrates that arose in subsequent geologic periods.

In the specimens in question, representing two different species, the jaws are located on either side of a slit-like mouth; and the jaws work sidewise against one another, not forwards and backwards as they do in typical vertebrates.

All this agrees with the location of the several pairs of oral arches (premaxillae, maxillae and mandibles) in the embryos of man and other vertebrates. It also agrees with the postulates and predictions of the arachnid theory of the origin of vertebrates.

IMPORTANCE OF THESE RESULTS

All this is not merely a new bit of evidence for evolution. It will require a new interpretation of many anatomical and embryological data, and a far reaching readjustment of our philosophy of evolution. We biologists are commonly content to point out this or that path which evolution has taken in the past, or may take in the future, but we have very vague ideas as to the relative value of the contributory parts played by heredity, by environments, or by the individual organism itself.

But here, it seems to me, we have the most impressive picture of the creative power of a specifically constructed organism that science gives us. For this initial pattern of bodily structures and functions dominates the whole sequence of evolutionary processes from sea scorpions to man. Environments, heredity, and natural selection are essential to the realization of its inherent potentialities, it is true, but they have made no radical change in the pattern itself, for something like a thousand million years.

There is no other known sequence of natural phenomena so vast, so complex, and so precisely determined in its inception, in the course it follows, and in the fertility of its results. Mankind has grown up out of this scorpion-like germ from an immeasurable past, with the same marvellous precision that today a new human being grows up from a specially constructed egg or germ cell.

To the biologist who really sees and feels these things, the age of miracles—real honest-to-god miracleshas not passed away.

DR. WILLIAM PATTEN Who completes 38 years of service this month as professor of Biology at Dartmouth and retires to an emeritus position

FIG. 3. OPENING UP THE RECORDS The beginning of a new lead, later deepened and greatly extended into the rye field on the right and at either end

FIG. 1. THE GENEALOGICAL TREE OF THE ANIMALKINGDOM Showing the probable relations of the arachnid and ostracoderm types to the higher vertebrates and to the many "compromise animals" that arose in the great transition period, some six or eight hundred million years ago

Fig. 4. Diagrams to illustrate the chief stages in the upbuilding of the head of man, including the transfer of the eyes and nasal pits nearly half way round the head to their permanent location; the atrophy of the gills and their transformation into certain parts of the ear and larynx; and the union of several pairs of oral arches, so as to close up the face and give it its characteristic shape. The jaws of Tremataspis are in one of the intermediate stages of this process.

FIG. 2. A RECONSTRUCTED SEA SCORPION (CLARKE AND RTJEDEMANN) Their remains were very abundant in Oesel. Some of them were formidable beasts, over six or seven feet long

FIG. 5. A PRELIMINARY RECONSTRUCTION OF TREMATASPIS Showing the slitlike mouth and the peculiar jaws that work sidewise instead of forwards and backwards. Some of the marginal plates were missing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

June 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleA Senior Fellow's Journey

June 1931 By John Butlin Martin, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

June 1931 By F. W. Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931 -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Meetings

June 1931