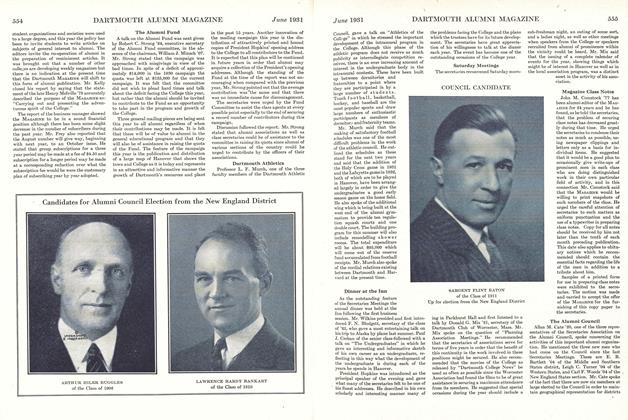

An educational experiment of outstanding interest, andnow of proved worth, is completing its second year atDartmouth. Senior Fellows to the number of six wereselected one year ago from the class of 1931 for the covetedawards which, without question, carry the highest honorto the recipients of any distinction given to undergraduatesby the College. The six seniors who have held the Fellowships this year are: Courtney Alfred Anderson of Jamestown, New York, William David Gomes Casseres ofCartago, Costa Rica, Abner Joseph Epstein of New YorkCity, John Butlin Martin, Jr., of Grand Rapids, Michigan, John Marshall O'Connor of Salem, Massachusetts,and Robert Schantz Oelman of Dayton, Ohio.

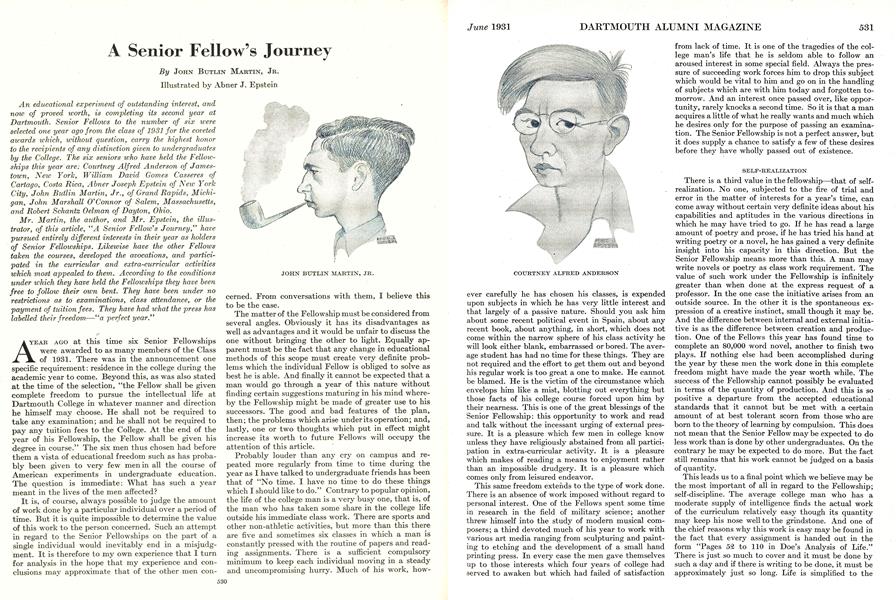

Mr. Martin, the author, and Mr. Epstein, the illustrator, of this article, "A Senior Fellow's Journeyhave;pursued entirely different interests in their year as holdersof Senior Fellowships. Likewise have the other Fellowstaken the courses, develo-ped the avocations, and participated in the curricular and extra-curricular activitieswhich most appealed to them. According to the conditionsunder which they have held the Fellowships they have beenfree to follow their own bent. They have been under norestrictions as to examinations, class attendance, or thepayment of tuition fees. They have had what the press haslabelled their freedom—"a perfect year."

AYEAB AGO at this time six Senior Fellowships were awarded to as many members of the Class of 1931. There was in the announcement one specific requirement: residence in the college during the academic year to come. Beyond this, as was also stated at the time of the selection, "the Fellow shall be given complete freedom to pursue the intellectual life at Dartmouth College in whatever manner and direction he himself may choose. He shall not be required to take any examination; and he shall not be required to pay any tuition fees to the College. At the end of the year of his Fellowship, the Fellow shall be given his degree in course." The six men thus chosen had before them a vista of educational freedom such as has probably been given to very few men in all the course of American experiments in undergraduate education. The question is immediate: What has such a year meant in the lives of the men affected?

It is, of course, always possible to judge the amount of work done by a particular individual over a period of time. But it is quite impossible to determine the value of this work to the person concerned. Such an attempt in regard to the Senior Fellowships on the part of a single individual would inevitably end in a misjudgment. It is therefore to my own experience that I turn for analysis in the hope that my experience and conclusions may approximate that of the other men concerned. From conversations with them, I believe this to be the case.

The matter of the Fellowship must be considered from several angles. Obviously it has its disadvantages as well as advantages and it would be unfair to discuss the one without bringing the other to light. Equally apparent must be the fact that any change in educational methods of this scope must create very definite problems which the individual Fellow is obliged to solve as best he is able. And finally it cannot be expected that a man would go through a year of this nature without finding certain suggestions maturing in his mind where- by the Fellowship might be made of greater use to his successors. The good and bad features of the plan, then; the problems which arise under its operation; and, lastly, one or two thoughts which put in effect might increase its worth to future Fellows will occupy the attention of this article.

Probably louder than any cry on campus and repeated more regularly from time to time during the year as I have talked to undergraduate friends has been that of "No time. I have no time to do these things which I should like to do." Contrary to popular opinion, the life of the college man is a very busy one, that is, of the man who has taken some share in the college life outside his immediate class work. There are sports and other non-athletic activities, but more than this there are five and sometimes six classes in which a man is constantly pressed with the routine of papers and reading assignments. There is a sufficient compulsory minimum to keep each individual moving in a steady and uncompromising hurry. Much of his work, however carefully he has chosen his classes, is expended upon subjects in which he has very little interest and that largely of a passive nature. Should you ask him about some recent political event in Spain, about any recent book, about anything, in short, which does not come within the narrow sphere of his class activity he will look either blank, embarrassed or bored. The average student has had no time for these things. They are not required and the effort to get them out and beyond his regular work is too great a one to make. He cannot be blamed. He is the victim of the circumstance which envelops him like a mist, blotting out everything but those facts of his college course forced upon him by their nearness. This is one of the great blessings of the Senior Fellowship: this opportunity to work and read and talk without the incessant urging of external pressure. It is a pleasure which few men in college know unless they have religiously abstained from all participation in extra-curricular activity. It is a pleasure which makes of reading a means to enjoyment rather than an impossible drudgery. It is a pleasure which comes only from leisured endeavor.

This same freedom extends to the type of work done. There is an absence of work imposed without regard to personal interest. One of the Fellows spent some time in research in the field of military science; another threw himself into the study of modern musical composers; a third devoted much of his year to work with various art media ranging from sculpturing and painting to etching and the development of a small hand printing press. In every case the men gave themselves up to those interests which four years of college had served to awaken but which had failed of satisfaction from lack of time. It is one of the tragedies of the college man's life that he is seldom able to follow an aroused interest in some special field. Always the pressure of succeeding work forces him to drop this subject which would be vital to him and go on in the handling of subjects which are with him today and forgotten tomorrow. And an interest once passed over, like opportunity, rarely knocks a second time. So it is that a man acquires a little of what he really wants and much which he desires only for the purpose of passing an examination. The Senior Fellowship is not a perfect answer, but it does supply a chance to satisfy a few of these desires before they have wholly passed out of existence.

SELF-REALIZATION

There is a third value in the fellowship—that of selfrealization. No one, subjected to the fire of trial and error in the matter of interests for a year's time, can come away without certain very definite ideas about his capabilities and aptitudes in the various directions in which he may have tried to go. If he has read a large amount of poetry and prose, if he has tried his hand at writing poetry or a novel, he has gained a very definite insight into his capacity in this direction. But the Senior Fellowship means more than this. A man may write novels or poetry as class work requirement. The value of such work under the Fellowship is infinitely greater than when done at the express request of a professor. In the one case the initiative arises from an outside source. In the other it is the spontaneous expression of a creative instinct, small though it may be. And the difference between internal and external initiative is as the difference between creation and production. One of the Fellows this year has found time to complete an 80,000 word novel, another to finish two plays. If nothing else had been accomplished during the year by these men the work done in this complete freedom might have made the year worth while. The success of the Fellowship cannot possibly be evaluated in terms of the quantity of production. And this is so positive a departure from the accepted educational standards that it cannot but be met with a certain amount of at best tolerant scorn from those who are born to the theory of learning by compulsion. This does not mean that the Senior Fellow may be expected to do less work than is done by other undergraduates. On the contrary he may be expected to do more. But the fact still remains that his work cannot be judged on a basis of quantity.

This leads us to a final point which we believe may be the most important of all in regard to the Fellowship; self-discipline. The average college man who has a moderate supply of intelligence finds the actual work of the curriculum relatively easy though its quantity may keep his nose well to the grindstone. And one of the chief reasons why this work is easy may be found in the fact that every assignment is handed out in the form "Pages 52 to 110 in Doe's Analysis of Life." There is just so much to cover and it must be done by such a day and if there is writing to be done, it must be approximately just so long. Life is simplified to the nth degree. There is so much to be taught and just enough work is arranged to just fill the allotted time. The average undergraduate never thinks of doing a piece of academic work which has not been set for him by someone. All discipline is external. The Senior Fellowship reverses the situation. It is sceptically viewed principally for this reason. And yet this setting up of the ideal of self-discipline, discipline applied from within, in itself makes the Fellowship worthwhile. Whether a man succeeds in this task of ruling himself depends of course upon the man. He may be successful or he may fail. It is our belief that it is better for a man to have made the attempt and failed than never to have tried at all. Post-college life is not by any means devoid of opportunities for self-discipline, but it is discipline of a slightly different sort. It is concerned with the making of bread and butter and generally far less with cultural growth. If a man has not disciplined himself to the point where he thoroughly enjoys attainment on the more intellectual side of life by the time he leaves college, his chances are small of ever achieving this attitude however honestly and uprightly he may run his business and his family.

THE DIFFICULTIES

If these are the advantages, what then are the difficulties in the application of the plan. The first of these begins before the Fellowship year has actually gotten under way. There is a very distinct tendency, facing the prospect of unlimited freedom, to map out programs Qf vast proportions which are in their very grandeur doomed to failure. It is axiomatic enough that a man's reach should exceed his grasp. An attainable ideal is admittedly an inferior one. But in this work of laying out foundations which it will take a year even to walk round there is the danger that the work of digging may never begin. A reasonably limited vision is, we feel sure, of more benefit than one of infinite and aweinspiring scope merely for the reason that a man stands a large chance of discouragement in his inability to make his work meet his words of prophecy. A year when all is considered is really a short time for any very great breadth of accomplishment. All of which perhaps sounds like a denial of the whole principle of the Fellowship. It is not; it is merely a safeguard against the difficulties following the failure of the first grand plan. Chief of these is a tendency to take a quick stabs at innumerable inviting interests with a resultant dissatisfaction in each case.

Of the men whom I have known during the past two years working under the Fellowship, most have gone through this gamut of talking too large, frustration, and then the inevitable grabbing at straws in the wind. Eventually in most cases there has been a settling on some smaller objective with a consequent feeling of having come to rest. This "lost feeling" has not been peculiar to any one of us. Nor has the individual been largely at fault. It has been a case of bad initial organization, but there have been none before us from whose experience we might have learned. With the men who succeed to the Fellowship from year to year it may be hoped that the same difficulty will not have to be gone through.

One further disadvantage which may be an advantage if we look at the coin from the other side is the uneasiness which each of us has felt at those times when we have indulged the luxury of doing nothing. And such moments, far from being inexcusable, are one of the greatest values of the Fellowship. If their product be only talk, they are nevertheless valuable, conversation being at once a major pleasure and a splendid luxury of life. At the same time, the award of the Fellowship throws into this luxury an uneasiness, a feeling that such idleness is somehow a shirking of the responsibility set upon a man with his acceptance of the Fellowship. It is possible to do no more than state the fact that the pleasantness of occasionally doing nothing at all is put at a premium by the Fellowship. It has another reaction also; that of making the holders of the Fellowship anxious to do work of such a sort as to be apparent to the surrounding college. Where this operates in any large degree it is a disadvantage and a detriment to the Fellow.

OUTSIDE ACTIVITIES

Two major questions arise in considering the Fellowship and its operation. There has been much discussion of the part which extra-curricular activity should play in the work of the Fellow during his year's freedom. There is no right or wrong answer, but there are several points to be made in opposition to the views of those who would have the Fellow drop all such activity in his last year. In specific cases the Fellows have had as a part of their year's program parts in various dramatic productions, the handling of the daily paper, and the promotion of intellectual and artistic interests in the life of the college. Anything of this nature can be overdone. It would be possible for a man to permit his entire time to be absorbed by such activity. It would be regrettable if such were the case. But within reason, I think, this work cannot be condemned. All that can be asked is that the interest, whatever it may be, is legitimate, that is, one which the individual finds a real pleasure in following. I say this for the reason that such activity may be as productive of self-development as any more completely scholarly or academic pursuit. I believe that extra-curricular work in the senior year should be at a minimum as compared with the three earlier years but that it should be altogether done away with, I see no cause to wish.

"six OR SIXTY?"

The second problem, which has been fairly propounded by those working under the regular undergraduate routine, is also one to which the answer is doubtful. "Why not sixty Senior Fellows instead of six?" it is asked. There is but one reply: that the experiment is still an experiment. The men working under the plan have learned much by experience not always pleasant. Much of what has been learned cannot be passed on, but a certain amount must accumulate from year to year. I do not believe that the system will remain unalterably as it is at the present time. I believe that changes will occur as those who watch the experiment become more certain of the results to be expected. While the unexpected is still happening it is the part of wisdom to limit the extent of the application of the system. Eventually, I feel sure, that in a form modified by trial and error an expansion of application will come. It is absurd to imagine that there are but six men in the undergraduate body capable of bearing the responsibility of leisure.

Finally there is the matter of selection. With this matter I have nothing whatsoever to do except in my privilege of holding an opinion as set forth in the few remarks which follow. It is my conviction that the Fellowship is best fitted, in fact perfectly fitted, to those men who have particular and acknowledged talent, the direction in which this tends mattering little. Men whose leanings are of a truly creative kind will always find in the Fellowship an adjustment which must make for creation. The difficulties of finding an attractive field of effort are already solved for these men. And thus the greatest hurdle in the Fellowship is removed. It has already been passed before the Fellowship is awarded. For such men orientation to the new freedom is almost automatically made. For the others, the men who have good minds but lack the creative spark, the chief factor must forever be a sense of responsibility. This is the prime requisite of the Fellowship and without it freedom is only a license to purposeless indulgence. A SUGGESTION FOR THE FUTURE

The second opinion which I would offer on the subject of the Fellowship is in regard to the above mentioned group whose interest is not directed by talent but, it might be said, by force of will. One difficulty, which I have not hitherto discussed because it is important to my present point, is that which men who are driven by no creative urge find in maintaining a consistency of effort. The artist may create in bursts of energy after and before which his faculties may lie comparatively dormant. Not so the individual who achieves by the mere force of his effort. Set down as briefly as possible my feeling is this: that men of this sort will find it possible to work more easily and satisfyingly with someone of their own choosing who would act in an advisory and to some degree in a critical capacity. Such a relationship would be in no way a check on the freedom of the Fellowship but might be expected to act in the way of the gyroscopic devices with which large vessels are equipped, as a stabilizer; if necessary as a rudder, but always as a rudder whose wheel is in the hands of the Fellow himself. The arrangement would be one where both the iniative and the discipline came from the Fellow but where, to change the metaphor, the advisor might act as a catalytic agent to prevent the action from ceasing altogether or from using up all its energy in bursts of unsatisfying effort. The opinion is offered only for what it is worth as the result of experience and observation. I believe that this is one of the changes whereby the Fellowship will achieve its maximum usefulness to the men concerned.

Perhaps an autobiographical ending will best serve to point up what I have so far said. I began with the grand plan, making the intellect of all Greece my province. I read her history, her philosophy, her poetry and drama, analyses of her religion, material on her art, and compendia on her achievement which began with Mathematics and ended with Medicine. I made page after page of laborious notes and wrote two or three papers. In addition to this I edited The DailyDartmouth, tried to keep up with current events and to read the more important of the new books. The end of the semester found me in the condition of the little boy who has eaten both pickles and milk in large quantities. In my desire to cover ground I had gorged on quantities of mental food. I had given far too little time to the process of assimilation. Then with the second semester I had a stroke of inspiration, but again I overdid the matter. "On the basis of my first semester's reading I will make an analysis of certain men who are deemed Modern Greeks," I said. "And for this investigation I will choose a mere four whose lives I shall investigate and whose work I shall come to know." I read Keats and read about Keats and soaked in the Keatsian phraseology and thought. Then suddenly I made a discovery: that Keats was as much a Modern Greek as I an Assyrian. One gone. I plunged forward hopefully into Swinburne. My hope was answered. And I knew then, though I would not admit it, that the other two men on my program would have to wait, for Swinburne was a Modern Greek. The result was a paper of some seventy-five pages length on the subject. Never have I had a task of a more enjoyable nature. Though the work was not inspired, it was my own and it wa,s produced only by the urging of pressure from within. There was no one to say, "Write me 5000 words on such and such a subject and have it in by Monday." Meanwhile I had been accumulating a list of reading which had slipped by me in the first three years. I turned to this with an eagerness to be at it. I had found my stride. But I had gone through some £5,000 pages of material to do so. I wrote and I read and I found time for sport and for conversation. The adjustment, though late, was attained and I was happy in the Fellowship. But it took time, much more time than I could spare from my very precious year of freedom. It is this period of wandering which it must be hoped future Senior Fellows will to a large degree be able to minimize.

So ends a year of intellectual thrills, of self-realization, self-discipline, and self-development. No longer, thrown upon my own resources, will I have that sickening, roller-coaster feeling at the pit of my stomach, the sensation of pawing with my feet for solid ground where there is only vapor. My feet have taken their grip. It is as though they had turned plantlike and cast out roots to hold me firm.

JOHN BTJTLIN MARTIN, JR.

COURTNEY ALFRED ANDERSON

JOHN MARSHALL O'CONNOR

ABNER JOSEPH EPSTEIN

ROBERT SCHANTZ OELMAN

WILLIAM D. G. CASSERES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

June 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

June 1931 By F. W. Andres -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Expedition to the Island of Oesel

June 1931 By Wm. Patten -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931 -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Meetings

June 1931