IF every scrap of wealth in the richest nation on earth, the United States, were blotted out completely, leaving the country a wilderness, the loss would be smaller than the economic cost of the World War. This loss, although spread in fact over mankind at large, was so great that the events of the next eleven years following 1918 were most surprising. By about the end of 1925, the enormous deficit already was made good. World production was actually greater than before the war; the currencies of most countries presently were stabilized; a solution seemed to have been found for the problem of war debts; and we moved forward into some four years of what looked like broad daylight. Then, with a speed still incomprehensible to most victims, came the total eclipse.

To understand what happened, it is necessary to keep before us two essential facts: that the world which emerged from the war was one whose economic order was primarily competitive, and that the destructiveness of the war was unprecedented. Depressions of the present character did not make their appearance until early in the nineteenth century, after individual initiative had largely supplanted direct political authority in regulating the production and distribution of wealth. And such depressions have been most intense and prolonged after great wars. The fundamental reason turns on the relation of these circumstances to an "unstable equilibrium." From the war onward, a process of "structural" changes had been creating ominous instability. In 1929, this process was joined by another, or one of "cyclical" changes, in an unholy alliance which produced the collapse.

UNSTABLE EQUILIBRIUM

A STABLE economic equilibrium refers, broadly, to any given distribution of productive resources, such as labor and capital, among the various products for which these resources are used, if it is understood that this distribution is not subject to rapid change.

The idea is best illustrated by the "competitive equilibrium" concept found useful by economists as an approach to many practical problems. This means that if competition were quite free, and resources could move like liquid from one industry to another, then any given grade of labor would be equally valuable in all industries, and the same thing would be true of any given quality of land or capital goods. As a result, the output of every product would be pushed just so far as caused the selling price to equal the cost. Thus every firm would break even on any resources which it hired from outsiders, and would have as its income the general rate of return on the resources which it owned for itself. Such an equilibrium would still be stable even if changes in the demand or cost of different goods called for the movement of resources, since the transfer could be made at once. From this it will be seen that in the actual world the equilibrium will be unstable in such measure as demand and cost change more quickly than resources can be redistributed.

But it is not necessary that productive power be spread out in this particular fashion. It is only essential that the distribution, whatever pattern it may take, remain fairly stable. For example, import duties tend to make outputs of protected articles greater than under free competition,

whereas monopoly tends to make outputs smaller. Yet tariffs and monopolies, once they are well established, need not cause instability unless they are changed. Given time, the equilibrium tends to adjust itself to whatever restraints society cares to impose; and it is upset in practice mainly by such changes as will now be described.

CYCLICAL AND STRUCTURAL CHANGES

CYCLICAL" changes refer to the more or less rhythmical ups and downs of business which seem to be possible without any great changes in tastes or methods of production. Precisely how they are brought about in competitive societies has never been explained in a wholly satisfactory way even by men who have devoted their best years to studying the problem. Nevertheless, it is clear that they are prompted largely by the workings of individual initiative.

The point may be illustrated from the homely "hog cycle." The cycle begins, say, with the price of pork markedly above the cost of producing it. From this it might be expected that the supply would soon expand. Instead, it decreases for a time: hogs are withheld from pork, or "consumption goods," and used for breeding, or "production goods." The later result is a distinctly bigger supply of pork than can be sold at cost. Prices drop greatly, leading at length to underproduction, to high prices, and so on, all over again. The periods of overproduction and underproduction are prolonged by the time required to expand and contract the stock of production goods. Further, the situation may be aggravated by bankers who during the upswing extend loans to some producers of a given commodity with little reference to the fact that other bankers are doing likewise for other producers of the same thing.

If expensive and highly specialized factory equipment is overproduced, reduction may require a long process of depreciation, made the more painful because the owners hope against hope and wait for competitors to make the first move. Further, as excessive supply depresses prices, stocks are dumped, making prices fall all the faster. Manufacturers cut down their purchases of raw materials and labor; the producers of these* curtail their demand for other things; creditors unable to collect act similarly; and what began as overproduction of particular goods results in general stagnation. Such is cyclical change where production or consumption are periodic, and where producers, instead of acting collectively on centralized information, are guided individually by prices in determining their outputs.

"Structural" changes are less rhythmical, but are likely to require greater transfers of resources. Underlying them is some radical change in demand or supply.

To illustrate, the demand for motor-cars increases. The automobile, however, is a comparatively new product : it is not merely a more efficient means of providing old experiences. The result is that the buying power attracted to it does not come from just one field, such as the wagon and carriage industry, but is drawn from industries in general. No other particular branch of production need suffer a staggering blow from the change. The danger, rather, is that the automobile industry itself will develop surplus capacity because the future demand will be overestimated.

Turning to a change in supply, consider a new method of production. The effect depends upon the nature of the demand for the product. Suppose that the product is books, and that the demand is "elastic"—that a given reduction in price increases sales more than correspondingly. Then the book industry can use more capital than before the improvement. But if the product is wheat, which has a decidedly inelastic demand, the result of an improved method of production will be excessive capacity in the industry.

Structural changes sometimes create a dangerously unstable equilibrium. They did so between the war and 1929. If a competitive economic order is caught, by the downturn of a cyclical change, in a condition of grossly inadequate readjustment to structural changes, its predicament is like that of an army attacked while on its way to a new defensive position. So the Germans might have been caught in the spring of 1918 as they retired to the Hindenburg Line. And so most of the world actually was trapped in the autumn of 1929.

STRUCTURAL CHANGES FOLLOWING THE WAR

THE most striking single fact about the growing maladjustments preceding the depression is the extent to which they are traceable to the war.* Certainly the war was not the only important thing. Yet how pervasive was its influence, and is still, may be seen the moment we turn from a mere description of the unbalanced conditions to the underlying causes. Briefly the main forms of instability are outlined below.

Among the crude food industries there was an especially strong trend toward excessive output in sugar, coffee, and wheat. Of such animal foods as dairy products, on the other hand, the supply was smaller than was justified by increasing demand. In the raw materials industries, surplus capacity was developing, or overproduction had appeared already by 1928-29, in rubber, mineral oil, silk, copper, lead, iron and steel, and nitrates. In the manufacturing industries, idle plant and unemployment were evidence of excess capacity, particularly in connection with such new commodities as rayon, radios, and automobiles. Incomes in some industries had fallen without a corresponding reduction in the output or capacity of other industries from which they bought. Cereal foodstuffs were worse off than manufactures, and minerals and metals than the cereals. In general, the output of production goods was becoming disproportionately large and badly distributed among the different industries using these goods.

There is no clear evidence that a fall in the general level of world prices, slight in any event, had much to do with these maladjustments. But the following factors told heavily.

The war had directly encouraged the expansion of productive capacity for certain goods beyond any probable peace-time requirements. Thus the acreage devoted to wheat increased in Canada, the United States, and elsewhere. After 1918, however, countries where the war had cut down output began to regain their former positions. Russia finally returned to her old export situation, or better, and her short crop of 1928-29 merely deceived the world as to the actual conditions. In certain industries, notably iron and steel, plant was extended during the war not only in countries already well industralized but also in Japan, China, India, and the British Dominions.

Certain "new developments," partly attributable to the war, aggravated matters. The wheat yield per acre was expanded rapidly in Canada, Argentina, Australia, and Russia by an increasing use of such machinery as tractors and "combines." The same result was furthered by new seed varieties, dry-farming, and the growth of fertilizer industries. In Chile, technical improvements led to large stocks of nitrates, and to excessive capacity. The war, by destroying huge amounts of capital, cleared the way for "rationalization"—for the adoption of better plant and methods. But the fact that capacity increased faster than actual output, thus delaying the scrapping of obsolete devices, led to a maladjustment which had become threatening by 1929. In certain relatively new products, especially such durable consumption goods as radios and automobiles, an overestimation of growing demand had a similar result, just as had been true of roads, canals, and railroads before certain pre-war depressions.

Rising tariffs were another factor. In our own country there was a desire to protect industries in the abnormal size to which the war had brought them. There was also an unwarranted fear that Europeans would dump on our markets great stocks of goods, which in fact they did not have and which their loss of capital would prevent them from producing for some time to come. The general increase of import duties on manufactures hurt our export market for farm products, thus intensifying into a crisis the agricultural depression which already existed. This of course reduced the demand of farmers for manufactured articles. The Fordney-McCumber tariff of 1922 was received with dismay among economists; and when still further increases in duties were proposed in the Hawley-Smoot bill, most of the members of the American Economic Association made a formal but unavailing protest. Newspapers, including the Boston Herald, warned "impractical" economists to leave tariff-making to "practical" manufacturers.

A growth of mergers and monopolistic practices further disturbed the equilibrium. Monopolies were unfortunate in three ways. The first way was to restrict output without reducing capacity correspondingly. The second way, closely related to the first, was to fall apart, more or less suddenly deluging the market with products which were either already in stock or which surplus capacity, formerly held out of action, was now set to producing. This happened to sugar, to coffee under the Brazilian "valorization" plan, and to rubber under the "Stevenson" plan. Third, by holding up prices, monopolies encouraged an increase of output and capacity by independents, and promoted, too, the use of substitutes. Monopolistic arrangements in iron and steel, to be sure, stuck together better, although their holding up of prices later caused great reductions in sales.

Conditions arising partly out of the war contributed heavily to changes in demand, and thus to further tension. Broadly, the changes took the form of a shift from "necessaries" toward "luxuries," and from "old" toward "new" commodities, especially durable consumption goods. Apart from the fact that some products attracting fresh demand were relatively new developments, two leading causes underlay the change. One was a considerable increase of income among people generally after about 1922. The other was the greater unevenness which the war brought about in the personal distribution of income. Had the resources necessary to the war been conscripted in the first place, as human lives were conscripted, or had the war debt later been paid off by a capital levy, this result would have been largely obviated. What actually happened was that profiteering, war borrowing, and the inflation and taxexempt bonds which attended the war borrowing, aggravated an inequality of distribution already so glaring as to be dangerous in any political democracy. The growth of instalment selling seems also to have played a part in changing demand. It served to intensify the demand for durable consumption goods during the boom, and then, because the goods were so durable and expensive, to check the demand at a later date.

Finally, a very serious disturbance arose from the peculiar international relations growing out of the war. The economic center of gravity had shifted from Europe westward. Stripped of capital equipment by the war, Europe in general, and Germany in particular, seemed obliged to plunge into debt to America for goods necessary to prevent appalling conditions at home. This fact, plus depreciated currency, turned gold toward the United States until after the middle of the 1920-30 decade, and later toward France and the Netherlands. America was at first glad to lend, since only in this way could she keep busy her productive capacity, swelled as it was by the prostration of industry in warridden Europe. We had turned quickly from a debtor to a creditor country. After about 1926 a more or less continuous stream of capital movements was set up from the United States to Europe, and, later, to South American countries. As a result, certain industries were built up to sizes which could be maintained only if continued capital exports from us enabled debtor countries to keep up their accustomed purchases from us. This situation was not serious for France, which does not rely greatly upon foreign trade, but it became critical for the United States and worse still for the United Kingdom.

There were other sources of maladjustment. For example, inordinate speculation was going on, and many security prices were far too high for underlying earning power. In brief, the situation as a whole was this: that a number of industries, with growing inventories and excessive capacity, were in an exceedingly vulnerable position. The "economic order" was like a human body weakened by excesses and ready to suffer violently from some malady which under ordinary circumstances it would have been able to shake off without serious consequences. Topheavy structures only waited for a downturn of cyclical change, or for a wrench to confidence in the international situation, to push them over.

The downturn of the "business cycle" was cruelly deceptive. The cyclical movement had been obscured by the aftermath of war and by structural changes. The tip-over was apparently the New York Stock Exchange crash. It seems to have been induced to some extent by the fact that foreigners, distrusting both exorbitant stock prices and the un- stable equilibrium in general, began a heavy withdrawal of funds from the New York money market. Confidence in world politics and economics was already diminishing. The sheer volume of reparations and inter-Allied debts was staggering. Loans to debtor countries had been put to unproductive purposes, the most sinister of which was armaments. The debt payment problem became the harder to solve because of rising tariffs, themselves due largely to war and the fear of war. That payments would become still more difficult for debtors if the price level fell only made the unstable situation the more ominous. International capital movements were checked suddenly.

The "downward spiral of deflation" is not a part of our sketch. The depression has now lasted over two years. Just at present there seems to be no pronounced movement either for better or for worse. How long will it last, and which way will it probably turn next? Some answer to these questions may be found by comparing the present debacle with its predecessors.

COMPARISON WITH OTHER DEPRESSIONS

THAT this depression is in some respects worse than any other must be admitted. Prices in general have fallen more than in any pre-war crisis. The production of structural materials and manufactures has fallen off more than ever before. In world trade, the quantity has fallen more than in any earlier depression, and of course the value has suffered an even worse decline. In industrial countries, unemployment has risen from 10 to 20 millions, the unemployed in manufacturing running from 25 per cent to 30 per cent in Germany,. Australia and the United States. Owing partly to the fact that wages have fallen less rapidly than the general cost of living, world food consumption has been wel maintained, although there has been a serious decrease in the consumption of durable goods. On the other hand, it is doubtful whether the volume (as opposed to the monetary value) of retail sales has shrunk appreciably in either Great Britain or the United States.

The main point of similarity between this depression and others consists in this: that long periods of heavy investment, in production goods and durable consumption goods, have been followed by long and deep depression. This makes clear one reason why great wars bring violent fluctuations. The large investments before 1920-22 had not been long continued, and they came at a time when war-time destruction of capital had not yet been repaired. This was not so before our present predicament. Prior to the violent recession which occurred in the 1870's, there had been rapid extension of the investment trades, and "new developments" in a marked degree. As now, there had been a war and its monetary disturbances; an agricultural crisis in which the prices of farm products fell faster than prices in general; fears that a gold shortage would cause falling prices; and a breakdown of stock exchanges. Fairly similar conditions preceded the almost unbroken depression of 1891-95; and the depression of the 1900's followed a great expansion of investment in electrification, non-ferrous metals, and chemicals.

But the following differences may help to explain the unusual profundity of the present depression. First, long-term loan rates have not fallen to the extent typical of major depressions. For example, bond yields declined much more in 1920-22 than in 1929-31, and the rates on loans extended for a year or more at a time fell farther from the pre-depression level then than now.

Second, in former depressions the fall of prices was greater, and the decline of output smaller, than now. Here monopoly has made itself felt for the worse, since recovery from depressions usually has begun by an increase of transactions rather than an increase of prices. Third, increasingly capitalistic methods in agriculture have made the fate of farmers more dependent than before upon conditions in capital markets.

Fourth, the closer international contacts of the present have given this depression its startling world-wide character. In the 1870's, the relative prosperity of South Africa, Argentina and Australia helped to lift us from our slump by improving our export trade; but less is now to be expected from foreign markets. Further, the international debt problem becomes progressively more critical as the fall of prices increases the burden of the debt. International capital movements are more important than ever, and the effects of tariff changes are more wide spread. Fifth, wages have not been reduced so readily as in past depressions. Sixth, the world is economically more mature. General expansion of demand caused by increases of population is a smaller factor than hitherto.

Most of these circumstances seem to make the present situation more than ordinarily grave, and to repress our hopes of an early recovery. None the less, a great deal can be done, especially through organized national and international action. Some things of immediate importance may be suggested first, and the question of fundamental preventives raised later.

FIRST AID

THE most imperative thing is to restore confidence. For this reason, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation deserves support. It need not result in objectionable inflation. Some credit expansion may even stimulate business; and the protection extended tended to banks and business enterprises is justified while the fear of failures is a menace to morale.

Second, further taxes must be submitted to, or even demanded, to keep body and soul to- gether among the unemployed. It appears that privately organized relief will not suffice. Third, is international debts. They should be scaled down radically, and at once. The main argument against doing so is that a dollar of cancellation means a dollar more in taxes. On this proposition, however, poli- ticians are misleading voters shamefully. Even if we wish to be purely selfish, the real question is this: are we willing to give up a dollar in tax remission if we thereby get more than a dollar with which to pay taxes? By our present stubborn attitude, we threaten to ruin our best customers, and to bring about a political and economic situation which will cost us dearly. Why not think less about the distribution of wealth, and more about its production, which depends so vitally upon trade with our neighbors? Great Britain has long since agreed to reduce German repara- tions to her as much as we reduce her debt to us. After the Napoleonic wars, and in the midst of a severe depression, she remitted to her former European allies most of the debt which they owed her. If we should now do the same thing, our action would go so far to stabilize Britain and Germany that it would put money into our pockets; and it would also contribute greatly to international good-will a;nd peace.

Fourth, tariffs must be reduced. Although it is not practicable to lower them rapidly, there are at least three reasons why a beginning should be made at once. First, there has not yet been time to effect a readjustment to the tariff increase made in the recent past. On this account, a more rapid return to stable conditions may be brought about by doing away with the recent increases than by waiting for resources to be redistributed according to existing tariffs. Second, standing pat on the present duties is having the practical effect of retaliation, and, therefore, of further barriers to trade among nations generally. This tends not only to aggravate maladjustments but to threaten tariff wars which are always capable of ending in armed conflict. Third, the worst of the existing maladjustments, or that connected with agriculture, is due partly to rising tariffs. Each increase in duties on manufactures, by decreasing foreign sales in the United States, decreases foreign purchases of American farm products. By lowering the duties, we could somewhat relieve the depression at the point where it is most acute. As a beginning, voters should insist upon repealing most of the increases of the Hawley-Smoot tariff. Fifth, long-term loan rates should come down. Here the initiative seems to belong, first of all, with bankers. R. G. Hawtrey, a British economist, warned us, when he spoke at Dartmouth four years ago, that central banks would only prolong depression by holding up loan rates. An outstanding example of the danger is the building trades, whose revival in times past has aided so materially in lifting us out of depressions. Such trades tend to be strangled by the excessive capital cost which high long-term loan rates cause. Sixth, there is the question of further reductions in wages. It is true that the "lag" of wages decreases profits, and, by holding costs up, arrests a growth of demand and production. It is true also that wages were scaled down more readily in former depressions from which more rapid recovery was made. Yet it is far from certain that further wage reductions will stimulate business greatly. For one thing, no corresponding decrease in costs will result, since wages are only one element in variable cost, and since there are also fixed costs to be considered. Again, the expectation that lower wages will reduce costs and prices may even decrease demand—make buyers hold out for still lower prices.

There is the yet more important matter of social justice, and the way workers feel about it. Why pick on wages while monopoly prices and long-term loan rates are still retarding the fall of costs? And if the wage lag has increased the real income of laborers, is not this a move in the right direction? Realism at least requires us to remember that laborers are willing to fight on this issue, and that a victory over them may cost more than it is worth. In another sense, too, reducing wages may aggravate the depression. A high ratio of overhead costs to variable costs is especially pronounced in those industries which sell largely to laborers. Hence a reduction in the buying power of laborers is likely to put such industries in an unusually hazardous position.

In any case wage reductions, where they cannot be avoided, should follow the principle of progressive taxation. Cutting all workers 10 per cent is like proportional taxation, and it is unjust. A 10 per cent loss of income is far worse for a poorly-paid than for a wellpaid man. It would be better, for example, to cut high-paid men IS per cent and low-paid men only 5 per cent, on the understanding, of course, that relative family burdens were also taken into account.

PREVENTION

THE present crisis must have taught us this lesson: that depressions are possible without preceding inflations. Hereafter, then, we should look less at finance and more at maladjustments, especially those created by structural changes. Our economic order must be modified substantially if it is to function competently under modern conditions. Yet great progress toward stability may be made without embracing anything so extreme as the Russian organization.

The avoidance of war probably takes first rank as a preventive. Even now we hear people propose war as a cure for depression! It is suggested, too, that a war with Japan would help matters. One way to get it, of course, would be to declare an economic boycott on Japan—although such a boycott might work if practiced by a real league of nations. But a war between the United States and Japan must only make depression much worse, everywhere, in the long run. If, however, a war becomes unavoidable, we should commandeer from the very first the resources required, and pay for them with a capital levy. Thus we might avoid inflation, a worse distribution of wealth, and a pall of endless taxes in the future. (Some Britishers are still paying other Britishers for the Battle of Waterloo.)

Sudden changes in international capital movements can be prevented only by more international cooperation. Even if it failed to prevent war, such cooperation could still bring under better control the changes in question. To illustrate, the "run" on the London money market last September might have been avoided had the Bank for International Settlements been in the true sense of the term a "central bank for central banks." Making it so, difficult enough in any event, is practically out of the question as long as we hold aloof from the League of Nations.

The moral in relation to tariffs and monopoly is already quite clear. The hitherto unending ascent of our import duties must stop, and a conservative decline must begin. Monopoly, where its suppression is not practicable, must be subjected to better control over investment and output. Again, the growth of monopoly may be checked by increasing the power of the Federal Trade Commission, and by getting rid of certain fence-straddling provisions in our anti-trust laws. There is now a menacing tendency to cripple the Commission by limiting its funds and investigatory powers, and then to call for stifling the body still farther because its performance is disappointing!

The most serious feature of the great increase of investment which precedes our worst depressions seems to be this: that the investment is not properly distributed among different industries. Experience indicates that even a very good system of commercial banking can exercise only limited control. The comparative freedom of investment banking from public control needs thoroughgoing reconsideration. Something like the Capital Issues Committee, which decided during the war the purposes and amounts for which securities might be issued, is worth consideration for our peacetime economy. And if financial control of production goods proves insufficient, we may next turn to government regulation or operation of equipment industries.

Finally, the matter of education may be mentioned. There is a lack of proper contact between, the public and the specialized students of problems which affect the public. Economists write mostly for other economists, specialists on government for other specialists on government and so on. But professional journals, although they are indispensable, cannot be understood by many laymen. This is what gives the Chicago Tribune its chance on the League of Nations, the Saturday Evening Post its chance on Reparations, and the average reader slight chance at all of finding out the truth about important public problems. If a democracy is to work well, ways must be found for teachers to reach people outside, as well as inside, the schools—and for the outside to reach the teachers, too.

POPULAR ECONOMICS—"Economists write mostly for other econo-mists" says Professor Knight in deploringthe lack of give and take between academicfaculties and their former students, menwho have assumed large responsibility aftercollege. "If a democracy is to work well,"he continues "ways must be found forteachers to reach people outside, as well asinside, the schools—and for the outside toreach the teachers, too.'""From War to Depression" has beenwritten by Professor Knight at the requestof the editors for the purpose of presentingan analysis of the causes of the depressionand suggestions of the controls appropriateto eliminate future maladjustments, asthese appear to an economist. He has fol-lowed Professor Ames' lead in making thepaper readable to the layman and thoroughlyconstructive. The several points defined andcommented upon are:1. Unstable Equilibrium2. Cyclical and Structural ChangesS. Structural Changes Following the War4-. Comparison with other Depressions5. First Aid6. Prevention

*A remarkable account of the events is contained in "The Course and Phases of the World Economic Depression," a book written under the supervision of Professor Ohlin, a Swedish economist, for the Secretariat of the League of Nations. It may be bought from the World Peace Foundation, Boston.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Manuscript Series—The First Volume

March 1932 -

Article

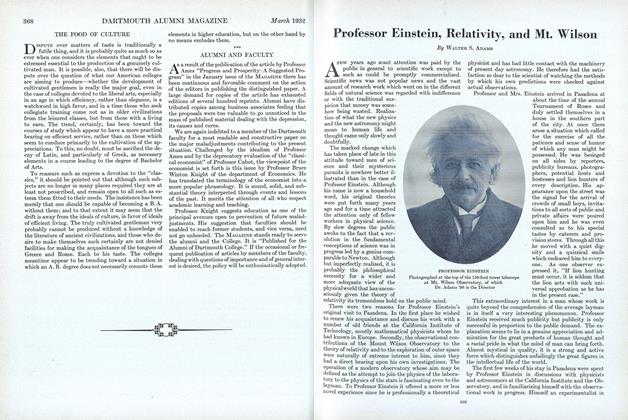

ArticleProfessor Einstein, Relativity, and Mt. Wilson

March 1932 By Walter S. Adams -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1931

March 1932 By Jack r. Warwick -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

March 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

March 1932 By J. Branton Wallace