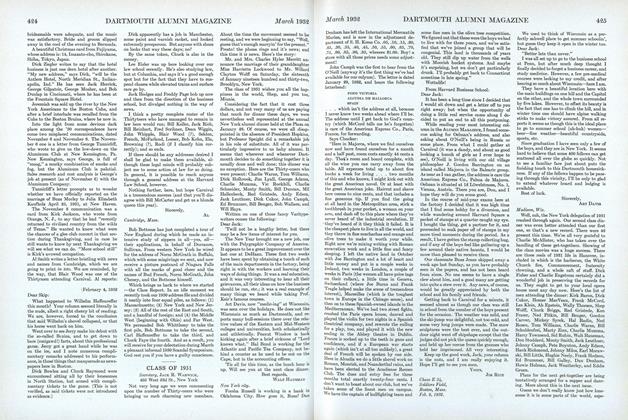

TURNING BACK TO 1743

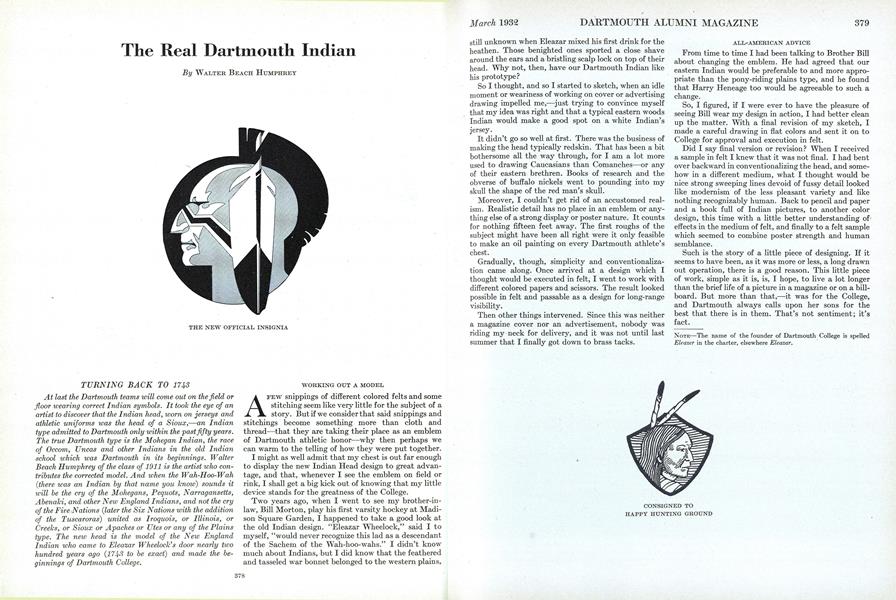

At last the Dartmouth teams will come out on the field orfloor wearing correct Indian symbols. It took the eye of anartist to discover that the Indian head, worn on jerseys andathletic uniforms was the head a Sioux,—an Indiantype admitted to Dartmouth only within the past fifty years.The true Dartmouth type is the Mohegan Indian, the raceof Occom, Uncas and other Indians in the old Indianschool which was Dartmouth in its beginnings. WalterBeach Humphrey of the class of 1911 is the artist who contributes the corrected model. And when the Wah-Hoo-Wah(there was an Indian by that name you know) sounds itwill be the cry of the Mohegans, Pequots, Narragansetts,Abenaki, and other New England Indians, and not the cryof the Five Nations (later the Six Nations with the additionof the Tuscaroras) united as Iroquois, or Illinois, orCreeks, or Sioux or Apaches or Utes or any of the Plainstype. The new head is the model of the New EnglandIndian who came to Eleazar Wheelock's door nearly twohundred years ago (17to be exact) and made the beginnings of Dartmouth College.

WORKING OUT A MODEL

A FEW snippings of different colored felts and some stitching seem like very little for the subject of a story. But if we consider that said snippings and stitchings become something more than cloth and thread—that they are taking their place as an emblem of Dartmouth athletic honor—why then perhaps we can warm to the telling of how they were put together.

I might as well admit that my chest is out far enough to display the new Indian Head design to great advantage, and that, whenever I see the emblem on field or rink, I shall get a big kick out of knowing that my little device stands for the greatness of the College.

Two years ago, when I went to see my brother-inlaw, Bill Morton, play his first varsity hockey at Madison Square Garden, I happened to take a good look at the old Indian design. "Eleazar Wheelock," said I to myself, "would never recognize this lad as a descendant of the Sachem of the Wah-hoo-wahs." I didn't know much about Indians, but I did know that the feathered and tasseled war bonnet belonged to the western plains, still unknown when Eleazar mixed his first drink for the heathen. Those benighted ones sported a close shave around the ears and a bristling scalp lock on top of their head. Why not, then, have our Dartmouth Indian like his prototype?

So I thought, and so I started to sketch, when an idle moment or weariness of working on cover or advertising drawing impelled me,—just trying to convince myself that my idea was right and that a typical eastern woods Indian would make a good spot on a white Indian's jersey.

It didn't go so well at first. There was the business of making the head typically redskin. That has been a bit bothersome all the way through, for I am a lot more used to drawing Caucasians than Comanches—or any of their eastern brethren. Books of research and the obverse of buffalo nickels went to pounding into my skull the shape of the red man's skull.

Moreover, I couldn't get rid of an accustomed realism. Realistic detail has no place in an emblem or anything else of a strong display or poster nature. It counts for nothing fifteen feet away. The first roughs of the subject might have been all right were it only feasible to make an oil painting on every Dartmouth athlete's chest.

Gradually, though, simplicity and conventionalization came along. Once arrived at a design which I thought would be executed in felt, I went to work with different colored papers and scissors. The result looked possible in felt and passable as a design for long-range visibility.

Then other things intervened. Since this was neither a magazine cover nor an advertisement, nobody was riding my neck for delivery, and it was not until last summer that I finally got down to brass tacks.

ALL-AMERICAN ADVICE

From time to time I had been talking to Brother Bill about changing the emblem. He had agreed that our eastern Indian would be preferable to and more appropriate than the pony-riding plains type, and he found that Harry Heneage too would be agreeable to such a change.

So, I figured, if I were ever to have the pleasure of seeing Bill wear my design in action, I had better clean up the matter. With a final revision of my sketch, I made a careful drawing in flat colors and sent it on to College for approval and execution in felt.

Did I say final version or revision? When I received a sample in felt I knew that it was not final. I had bent over backward in conventionalizing the head, and somehow in a different medium, what I thought would be nice strong sweeping lines devoid of fussy detail looked like modernism of the less pleasant variety and like nothing recognizably human. Back to pencil and paper and a book full of Indian pictures, to another color design, this time with a little better understanding of' effects in the medium of felt, and finally to a felt sample which seemed to combine poster strength and human semblance.

Such is the story of a little piece of designing. If it seems to have been, as it was more or less, a long drawn out operation, there is a good reason. This little piece of work, simple as it is, is, I hope, to live a lot longer than the brief life of a picture in a magazine or on a billboard. But more than that,—it was for the College, and Dartmouth always calls upon her sons for the best that there is in them. That's not sentiment; it's fact.

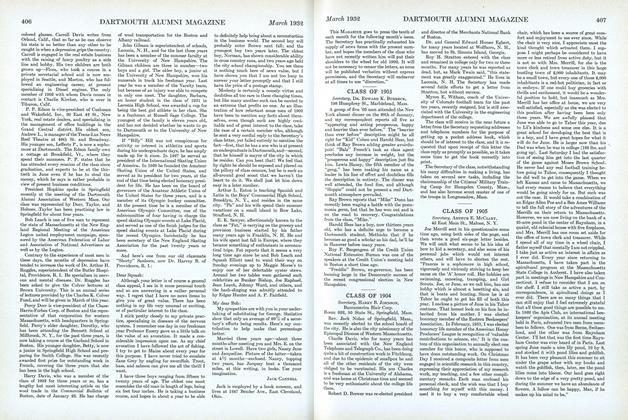

THE NEW OFFICIAL INSIGNIA

CONSIGNED TO HAPPY HUNTING GROUND

NOTE—The name of the founder of Dartmouth College is spelled Eleazer in the charter, elsewhere Eleazar.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFrom War to Depression

March 1932 By Bruce Winton Knight -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Manuscript Series—The First Volume

March 1932 -

Article

ArticleProfessor Einstein, Relativity, and Mt. Wilson

March 1932 By Walter S. Adams -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1931

March 1932 By Jack r. Warwick -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

March 1932 By Arthur E. McClary