TODAY THE press is detailing countless innovations in the fields of higher education; people who once disposed of the university or college graduate as an impractical visionary are now developing a live and vital interest in the aims of higher education, in the men that the various processes of this same education turn out, and in the changes and experiments that are continually taking place in our progressive colleges. Projects like the tutorial system and House plan at Harvard, the advanced scheme of Honors courses at Swarthmore, or the rejection of the time-serving coursecredit requirements in favor of a system of educational attainment at the University of Chicago, are all important signposts which point the way not only to this increased publicity of educational experiments but also to the awakened interest of the general public in these attempts to realize more fully the true aims of education.

Preceding this significant revival of wide-spread popular interest in revisions of curriculums, one may discern the rise of undergraduate interest in the aims and conduct of education; there was a time when the ideal that was set before the average prospective college entrant was to accomplish the requirements of his Alma Mater with as much concentrated mental discipline as possible. The courses that were prescribed were many and difficult ; little opportunity was given for freedom of choice, and for the pursuit of particular interests. Latin and Greek were good training for the mind; only through these required courses could the requisite severe mental discipline be enforced. That was the old theory, and the tendency was to require much and to expect little. In the colleges of today, the pendulum is swinging very perceptibly to the other extreme—more and more one is brought to the realization of the fact that the modern college is requiring far less, and expecting more. Between these two concepts lies a world of change and of progress; the question that flashes into one's mind is, "How did all this apparent reversal of attitude occur?"

In order to answer such a question, it would be necessary to go far back into the earliest history of the growth of higher education, and to trace the line of educational development down through the influences of the English universities, and the subsequent domination of German ideals and methods. Fortunately enough for the interests of pleasant reading, there is not space to go delving into the crosscurrents of the social history of education. Suffice it to say that for a long time the sole and only purpose of higher education was purely intellectual—colleges existed to train ministers, or to prepare for the professions, and there was little time for outside nonsense. With the passage of time, we find that the old family unit, which has been the bulwark of American culture and civilization, is breaking down, and that the growth of huge industrialized centers of population which we call "the big cities" brings a great disrupting influence into the home life and fundamental environment of the children. Consequently, the college of today finds itself more and more responsible for the totality of a student's life for his four years as an undergraduate. In times past, it was possible to emphasize solely the development of the mind; now the ideal is an all-round development in the Hellenic sense. Such a change as this in the ideal of the college was not accomplished in the wink of an eye; on the contrary, this new ideal of the totality of responsibility in a college came only by a long and gradual process of evolution, progressing oftentimes by the trial and error method; many vast and sweeping plans for progress were tried and found wanting when it came to the pragmatic test. Thus we see the modern liberal college as we have it today—it is vastly different from the liberal college of a half century ago, and yet there is a distinct and direct line of inheritance which one may trace down from its parent beginnings; the daring and radical innovations which appear to burst into view overnight like gigantic mushrooms springing up through brown leaf-mold have in reality matured from countless seeds of thought sown at irregular intervals in the course of the evolution of the historic college.

II

IT seemed imperative to set forth this conception of the present liberal college as the outgrowth of years of cumulative labor all progressing steadily toward the changing ideal of what the college should be, in order that various projects now in effect in modern education might not seem to be mere over-night creations, but as they are in reality the outgrowth of a certain constant seeking after an ideal college and an ideal educational system by men of vision and purpose. With this dynamic conception in mind, my purpose is to point out some of the main features of the curriculum in its present state at Dartmouth, to compare our educational policy here with my own ideal of higher education, and to suggest a few changes in our present system as they occur to an undergraduate at the end of four years under the educational process.

This article does not purport to be representative of undergraduate opinion or belief at Dartmouth; it is simply the thought of one undergraduate, whose ideas have been molded from their amorphous plastic state to one of more or less crystallized coherence by discussion of various points with other undergraduates, with faculty members, and with people entirely outside the Dartmouth influence who know other programs now in effect, who have a certain detachment which makes their opinions more completely objective and impartial. There are countless criticisms which may be made of this sort of a survey by a man who is still a member of the college—he is often prone to hasty judgment on a basis of unconfirmed data, he lacks the experience to discriminate between visionary and impractical ideals and those that are made of sterner stuff, his temporary residence in Hanover over a mere four years does not give him an adequate background for judgment, he is unable to attain the templa serena of the more mature spectator who can view the process as a whole in an attitude of detachment. All these criticisms and many more are quite valid in the main, but they fail to take into account any advantages which may lie inherent in the situation—the undergraduate is the object, not the subject, of this educational process in hand, he brings with him often a freshness of viewpoint and a greater openmindedness and receptivity to new ideas, and he has a closer understanding of the undergraduate attitude. For all these reasons it seems to me that there may be something of value in just this sort of survey; of necessity it must be superficial, and comprehensive at the expense of details, yet I feel that it tends to accentuate the spirit maintaining that a college should be a cooperative enterprise between students and faculty and to show the dynamic side of the college which is often forgotten as one views the whole. I supposed that I had a fairly decent idea of what the curriculum was at Dartmouth before I even thought of making a survey; in my mind the curriculum was a regular course of study which varied slightly with the individual interests, but which was a rather stable and static thing. It was only when I tried to hold the college off at arm's length that I saw how radically I had been duped by my own senses—the curriculum no longer seemed a static, quiescent body of courses, but instead became a continuous dynamic stream, where all things were flowing as an integrated whole in a state of flux. Previously, I had been carried along with the stream without more than a passing thought of this continual rhythm of change in the college; for the first time I saw the college steadily and saw it whole for a brief instant. It is this constant shifting and interplay of forces which makes a curriculum dynamic and progressive, or the lack of it which makes for sterility and inertness; how, then, does our curriculum appear at Dartmouth?

III

IN the first place, through the medium of the Selective Process of admission, Dartmouth endeavors to select the men who are the potential leaders, who have the will and the ability to derive the most benefit from a liberal college; any college which thus limits the number and quality of men to be admitted immediately assumes an increased responsibility to these men, for their balanced development, and for their general welfare. The basis of the Selective Process, which annually picks out some 600 students from a list of over 2000 well-qualified applicants, lies in the fact that the college wants men of high scholarship, good character, and promise of leadership among their fellows in later years; the applicant's school record is carefully examined, personal ratings from various sources are correlated, and, where it is possible, the applicant is interviewed by a Dartmouth alumnus.

Let us pick out a certain applicant and assume that he is notified, about the second or third week in April, of his admittance to Dartmouth College. He is now a subfreshman, and has the pleasant task of selecting his dormitory room, and making plans for the long step from high or preparatory school to college. In the fall, as September touches the first of the New Hampshire leaves with autumn color, he arrives in* Hanover eager to enter upon these four years which can mean so much to him. He finds that there are helping hands which assist him in bridging the gap between secondary school and college, that try to acclimate him to his new surroundings. Along with the rest of his classmates he takes his physical exams, his swimming test, and receives his matriculation certificate. If the process of adjustment were only as simple as that, a great many troubles would be avoided; unfortunately, for the first couple of weeks, the freshman's mind is in a turmoil as he faces this world which is so new and fascinating, but so entirely unlike anything he knows. He goes to orientation lectures on the history of the College, on the art of study, on the curriculum, on care of health; he is conducted through the new Baker library and shown the vast facilities for reading and study of all kinds that the College affords. After nearly a week of this sort of thing, classes begin for him in earnest; he is required to take a semester course in Industrial Society giving him a general survey of the social sciences and contemporary problems, and a semester of Evolution, a general survey of the physical and biological sciences grouped about the central unifying concept of Evolution. In addition to this, a basic English course is required for all freshmen. For his other two courses, he will probably elect a science, and a foreign language. During this first week he will take a general intelligence test, and various placement examinations for use in allocating him to a section with men of nearly equal ability. The freshman faculty council will be watching his work from time to time, and if he appears to be having difficulty with a course, or courses, a member will go to his instructors and attempt to find the solution for his problem. He will have an upperclassman to act as his advisor throughout the year in regard to matters which may perplex him from time to time. The Dean of Freshmen himself will call him over to the office during that first semester, and he will find to his surprise that he is not starting out in Dartmouth unknown and alone among a strange group; from the records and material of his application blank, and various reports already filed by his instructors or men on the freshman council, the Dean will know a great deal about him and his interests, and will be able to meet his problems sympathetically and intelligently. Thus the first year is given over to the attempt to make the leap from secondary school to college not too abrupt a change, and to give the freshman ample opportunity to find himself in his new environment, and to make the necessary adjustments.

IV

SOPHOMORE year beings with it an attitude of scornful superiority, a fraternity pin on the vest, and, all too often, the so-called "sophomore slump." There seems to be no known advisory system which can cope with this pernicious malady, which may last from a month to a year and a half in the most severe cases. Let us assume that our sophomore recovers in time to pass his two social science courses, and his physical science, with two elective courses which he may choose at his own discretion. He now has behind him a fairly broad comprehensive background of information about the various branches of knowledge, and he has fulfilled all his requirements for a diploma, with the exception of the requirements of his major study. Thrice a week for two years he has betaken himself to the gym or to the various outdoor sports to complete his recreational activities requirement, and he has passed his semester of Physical Education. Now comes the time for him to decide upon his major study. Through his background and past experience, he has learned that for some studies he has nothing but a distinct aversion; for others, a mere passive neutrality; a third group, fortunately small, is composed of subjects which he has enjoyed in particular, or which he feels will be necessary for him in his life work, or for which he has the smallest comparative distaste. With the aid of consultation with various faculty members, and an excursion into vagabonding from class to class to find out more about his interests, and long perusal of a very valuable booklet entitled "Organization of Courses," our student makes his choice of a major, and plots tentatively the courses he will follow during the next two years. All this takes place in May of sophomore year, and now he has a definite goal in view, and an opportunity to build a more specialized knowledge on the general foundation he has been laying.

Junior Year beings with it class blazers, many tentative tests of developing powers, and a deepened appreciation of the underlying significance of college. During this year, the junior will take two courses in his chosen subject, with one complementary course in another field related to the major; two courses are left open for free election. Senior year, following hard on the heels of what scarcely seems like a whole nine months of college, brings senior canes, and senior cares, and also a certain wistfulness as the wheels of Time go on turning inexorably faster and faster. This year two courses are required in the major, together with the equivalent of a third course which is prescribed by the major department. This third course is usually the 101-102 or coordinating course, conducted in small seminar groups along the lines of the preceptorial system; its purpose is the integration of the various courses of study in the majdr department, and the guidance of independent research and reading. Two courses again are open for free election. The last of May brings comprehensive examinations, which every senior is required to pass unless he is preparing to enter Tuck, Thayer, or Medical School. These examinations cover the entire field of the major, and do not test the courses which one has taken as separate units, but are for the purpose of ascertaining the student's grasp of the subject as a unified whole.

V

IN tracing the career of this Average-Citizen-To-Be, it has been impossible to mention several very interesting and important projects which are carried on for the men who are a little above the average. The first of these is the Honors groups for men who at the end of the sophomore year have an average of 2.6 (B—), or have shown good ability in the department in which they have elected to major. These men may constitute an Honors group in their major department, where they are treated with attention to their individual needs. They are not held to the usual rules of class attendance, but instead meet in small groups once or twice a week with the instructor. The object is to encourage such men towards self-education by allowing them as much individual freedom as possible, and by permitting them to work at a pace faster than the general rate of the college. The Honors system varies greatly from department to department. In some instances it is little more than the pursuit of the regular courses with more time devoted to individual conferences; in others it has been found feasible to allow a maximum of freedom and independent work. At the end of each semester men who have displayed unusual ability in the general courses may be transferred to the Honors group, and conversely, men who have failed to avail themselves of the opportunities of this group may be shifted back to the general sections.

Another project which has created an unusual stir is that of the Senior Fellowships; toward the latter part of the year a small group of men are selected from the junior class for the distinction of the award of a Senior Fellowship. A Senior Fellow is required to pay no tuition fees to the college, to attend no classes (although he has the privilege of attending any he desires), and is obliged to take no examinations; in short, to a few men of exceptional merit a year of complete and perfect freedom is given for. whatever purposes they may think best. At the end of the year, the degree is awarded automatically; the only requirement is that the Fellow be in residence in the College during the academic year. An experiment of so radical a nature as this is constantly under the scrutiny of interested people of all sorts, from the ardent protagonists of the plan to the dubious skeptics, all of whom are watching intently to see how the experiment stands the test of actual application. The Senior Fellowship is now in its third year of operation, and has proved itself to be not only an experiment of outstanding interest, but one of great worth as well.

This year there are seven seniors who are enjoying the benefits of a year of untrammeled freedom; the question immediately comes to mind: "What have they done?" Personally I have always felt that the true purpose of the Fellowship was not to be able to point out so many thousands of words neatly packed into papers, nor so many courses attended, but that its ultimate value would come from the necessity of standing on one's own feet, of thinking one's problems through to the end, of following up special interest for which there never has seemed sufficient time. The use which one makes of the Fellowship will depend entirely upon the individual, and this opportunity to work and think and read in absolute freedom will have a value which only the Fellow himself can begin to estimate.

It might be interesting to glance very briefly at the activities of these seven as they have progressed thus far this year. One has made a special study of the field of modern European history, with particular attention to the international angle in modern affairs. Another started with the idea of studying Power as a central concept, and has found time to enlarge his appreciation of music and art at the same time. A third has made the Creative Mind and its relation to Genius his particular field, and has found this topic so inclusive that he has also been able to delve into many of his interests in History, Comparative Literature, and English. Still another found the first semester profitably spent in a careful study of American literature, with special emphasis on Mark Twain; now his interests are engaged in the field of Political Science. A 60,000 word paper on the development of liberty in the western world was one of the creative products of another of this group of Fellows, together with a comprehensive study which gives a good survey of several thousands of years in the world's history. A Fellow whose creative ability is particularly strong utilized all of the College's facilities for doing practical work in the field of music, and in extending his knowledge of theory and composition. The last of the group, finding his interests to be primarily in the English courses, followed the English Honors courses during the year, and worked with the central concept of the relation of literature to life. This very brief summary shows some of the main interests of the Fellows of this year's group, but does not pretend to evaluate the work done by this band of seven, either in its worth to the individual or to the world at large.

Leaving the Fellowship for the time being, and turning back from a project of the final year of college, we come to an experiment which concerns a man before he even enters Dartmouth College—the Junior Selection plan. A few outstanding applicants for admission to Dartmouth willbe selected at the end of their penultimate year of preparation.

The venture is a new and striking one, but the principle underlying it is the same which led to the establishment of the Honors courses and the Senior Fellowships. The object of this plan is to give boys of exceptional ability as much freedom under expert guidance as is possible; each student selected for admission under this plan will be obliged to submit enough formal entrance credits, and in addition will have to conform to the requirements of his own school. This does allow a great deal more leeway than any college entrant has previously been granted, but at the same time insures competent supervision and the fulfillment of ordinary requirements. Twenty men have been selected for the class of 1936 under this method; at present it is still very much an experiment, untried and unproven; its underlying theory would seem altogether sound and progressive, but time alone will give the decision. In the words of the college, it is hoped "that this new move will focus the attention of secondary schools on the desirability of having their outstanding men enter college with a zest for its educational menu and for development along lines of their own interest and power in place of a blase or a browbeaten attitude, either of which is more fatal than insufficient or faulty preparation."

VI

THIS, then, is the present set-up of the curriculum at Dartmouth in a very sketchy and summary presentation; the essentials of the curriculum are stated, but in a broad and sweeping fashion which does not permit of any detailed analysis. Before going on to comment on the advantages and disadvantages of such an outline of study, it would seem wise to state the standard which I am going to take as a sort of educational yardstick for purposes of comparison.

In starting upon this consideration, I said that the college itself was in a constant state of change; it is precisely so with the ideal of a college—the goal which the college proper is striving to attain. Again, there seems to be no mathematical ratio which will state the relation between these two rates of change; no matter how fast the college tries to adjust itself to new needs and to the new ideal, the dynamic shifting pattern of the ideal always manages to keep far ahead of this process of readjustment; sometimes the ideal strays from all previous paths, towing the college behind it, only to leap nimbly back to its old position, leaving the college to retrace its steps as best it may. The history of the growth and development of colleges is full of just such dashes into the by-ways, followed by a slight retrogression in the return to the original paths. The chart of the progress of the college, however, would be a fairly straight path, with here and there a few retreats and momentary halts, due to incorrect readings of the signposts along the way, or to the failure of some noble theory to measure up to expectations in actual practice. It is a tremendously difficult task to attempt to fix the kaleidoscopic shift of the patterns of the ideal for a period long enough to insure a steady or accurate view; due to variations in social conditions and public opinion from time to time, the ideal never remains exactly the same for any two instants in eternity. The basic pattern remains fairly constant, however. I should like to state this basic constant of my ideal of the college as briefly as I can.

In trying to correlate my ideas on the subject into a fairly coherent whole, I found them in a tremendously nebulous state; the more I read of the statements of great thinkers in regard to the aims and purposes of a liberal college, the more I came to believe that there were two, and only two, primary objectives in the liberal college today. The first aim is stated clearly and concisely in President Robert Maynard Hutchins' address at the University of Chicago last year; he said:

"the purpose of higher education is to unsettle the minds of young men, to widen their horizon, to inflame their intellects, and to teach them to think—to think straight if possible—but always for themselves." The more I thought of this statement, the more I felt that there was something omitted which was in itself a very vital concern of the college of today; no matter how clearly a college may train a man in the process of thinking, it is a one-sided and distorted development unless along with it comes a greater knowledge of the art of living, the ability to lead the fullest and richest possible life. All other statements of the aims of a liberal college seemed to be included in the statement of these two purposes; accordingly I decided that the nearer a college approached the realization of these two ideals, the greater its success as an institution of higher learning would be, and vice versa.

With my standards for an ideal college now selected, the next step was to ascertain what means seemed best for the nearest approach to these standards. A college with these standards in view has to remember that the students enrolled in its ranks are alive, and that the purpose of the educational system is to guide their selfdevelopment ; this means that the teachers also have to be alive with living thoughts. Again, education must not emphasize what the teacher has said, but what the student has grasped. The mere grasp of a few facts is all very well in itself, provided that the student relates them to other parts of his knowledge; facts as mere general bits of information are inert ideas, and, as Professor Whitehead tells us, are positively harmful in modern life.

We must proceed on the assumption that the student is willing to learn, once his intellectual interest can be aroused; the primary purpose of the college is intellectual, and all other things must be subordinated to their proper places. The difficulty is to show the student that this intellectual interest is primary, and to arouse his interests so that he will be convinced not from outward compulsion but from a firm inner belief. In order to accomplish this result, the intellectual interest must be connected at all times with that phenomenon which is of highest interest to us all—life, in all its manifestations. If a student can be made to feel that he is accomplishing a study which bears directly on life, and not merely executing a series of trivial "intellectual minuets," half the problem is already solved. In the beginning, then, let us try to awaken this vital interest, and foster a sort of general culture for our men—culture here will mean a combination of activity of thought, receptiveness to beauty, and humane feeling. We are aiming towards the acquisition of the art of the utilization of knowledge, and this is the first step. Let us bring our undergraduates under the influence of a band of imaginative scholars, who can impart the facts that are needed for raw material before one can begin to think, and who can impart these facts imaginatively, showing a definite relation to life and to the other branches of knowledge. Knowledge is very much like fish—it must always be invested with a certain freshness, and if allowed to stand idle in the pleasant sloth of mental inactivity, it smells no better than the fish heaped up in the sun, and becomes a putrefying mass of inert ideas. Once this general culture which fosters an activity of mind is well on its way, a degree of specialization may be introduced which will utilize this activity.

Until the secondary schools which prepare for college entrance come to realize that the emphasis must not be laid upon mere memory as opposed to rational thought, that a certain intellectual aggressiveness and audacity is necessary in facing the problems which arise, and that education is a process of self-development and not a superficial veneer which may be summarily applied from without, the college must spend a considerable amount of time in overcoming the sterility so often engendered by the preparatory schools. If a man can be brought to realize the true aim of the college at an early stage of his career, and his dormant intellectual interests can be aroused, his four years will be a rich and full and purposeful period of activity.

The real purpose of the college is being achieved from a social point of view—men are being turned out who have learned to think, who know how to live with their fellow beings, and who are fitted to undertake the responsibilities of intellectual leadership in the world around them. The thinker is the man who has learned to wonder about the universe about him, the man with whom he lives, the thoughts that impinge upon his ■consciousness. The college which is going to turn out an increasingly large and increasingly good group of potential leaders must remember that the exceptional man, the man who is above the average, must be given ample opportunity to develop to the limit of his capacity; the majority of the effort cannot be spent in endeavors to bring the whole group up to a uniform minimum of mediocrity, while the man of greatest potentialities struggles along without due attention to his needs, if the greatest social good is to be attained. The end in view will be to present a thorough knowledge of a small field, to develop the powers of thought by applying them to actual problems, and to maintain the fire of intellectual interest so that the four-year period will not mark the end of intelligent thought and interest in contemporary ideas, but will merely serve as a stepping stone into wider and even more fascinating fields.

VII

IT certainly seems like a tremendously Utopian and fabulously impractical scheme, on first glance, doesn't it? Before passing a final judgment, however, let us turn back to the curriculum of Dartmouth College, and see if there is an impassable abyss between our two conceptions. The Selective Process now in effect makes an effort to choose men who will be good material for the educational process; each year the incoming class shows a tangible improvement over the one before it. The entering freshmen find that provisions are made for their orientation in their new life, and any of them who find problems confronting them which are difficult to solve find capable men who are at hand with intelligent advice. The courses that they are required to take are designed to stimulate their interest in problems which confront the world today, to give them a comprehensive background of information, and to give them a brief glimpse into the expanses of knowledge which lie 111 the distance. Attempts are made to place men of nearly equal ability in the same section in their courses; men who qualify for advanced sections are allowed more freedom and more initiative in their work.

During sophomore year, more freedom is allowed, and a wider range of work is accomplished; through personnel work and individual conference, an attempt is made to determine a man's interests, so that he may choose his major study with more care. The last two years are devoted to the major field, with enough time allotted outside that study to permit a man to continue other interests he may have. Work is much more independent, yet the aim is to require a thorough mastery of his subject, as tested by a comprehensive examination at the end of the two years. Here the emphasis is decidedly on thought and not memory, on grasp of subject as a whole and not on individual courses, on relation of the subject to the field of knowledge as a whole, rather than as an absolute value in itself.

The special projects which have been mentioned the Junior Selections, the Honors courses, and the Senior Fellowships—represent an attempt to meet the needs of the individual of exceptional ability, and to encourage him to develop the best that is in him, under careful guidance and special privileges, with an attendant increase in responsibility. It means that the College is recognizing the fallacy of devoting all its time and energy to raising an entire group to a low level of mediocrity, and is trying to give the superior scholastic group an opportunity for independent and active learning; it is assuming a will-to-learn on the part of the student, and that is a distinctly healthy sign.

So much for the curriculum proper at Dartmouth; if we were to stop here, however, one might justly tax us with omitting any consideration whatsoever of what Dartmouth is doing toward making the art of living of practical value in the lives of her undergraduates. One cannot enumerate all of the facilities and activities which contribute toward the all-around development of the undergraduate. One might think of Baker Library with its luxurious Tower Room and its programs calculated to make the enjoyment of good reading an essential in every man's life; one might stroll down toward the gym and investigate the ever-widening sweep of the intramural program which provides athletics for all. Again, one might attend activity night during the first week of college, and remark on the scope of extracurricular activities, which supplement the program of the College by providing an outlet of constructive sort for every man's interest—literary, liberal, and philo- sophical groups; publications, managerships, Dartmouth-out-of-doors; inter-collegiate sports, dramatics, musical organizations; parties, proms, and peerades. The whole panorama of Dartmouth's extra-curricular program passes before one's eyes. One might run up to the President's Office and take a cursory glance at the programs sponsored by the College for the edification and delight of the community—lectures by men of such national repute as Sherwood Anderson, Lewis- Mumford, Charles A. Beard, Stefansson, Whitehead, or Thomas Craven; a concert series including such notable musical attractions as the Don Cossack Russian chorus, Roland Hayes, Lily Pons, the Detroit Symphony, or the London Players' production of "The Beggars' Opera." No matter where one may turn, one finds that provision has been made for the fullest and richest life that one could ask. The skeptics will mutter in their beards—"the mere booking of such attractions does not necessarily mean that the undergraduates attend." They are wrong; a lecturer presenting a program of merit is sure to find a large and interested student audience. It is true that it is quite possible to lose sight of the forest for the trees, in becoming too much involved in these many and diverse outside interests; taken as a whole in their proper place they fill a very present need in the life of the undergraduate, and supplement the intellectual purpose of the College both by extending and expanding the fields of interest.

VIII

So far all that has been shown is the correlation between the curriculum and its supplementary branches and the ideal of the college as a whole; it is quite true that an ideal is never to be reached, for if such a thing were to occur, all the wheels of progress would come to a standstill for lack of a goal—at least, until a new ideal were found. It is even so with the curriculum at Dartmouth College; it is always undergoing change, and its component parts are never at rest, but are ever shifting to find a better adjustment. My story would not be a true picture, were I to fail to suggest some logical changes which would lessen the gap between the two pictures. I make these recommendations only after a period of reflection and of consultation with various people of more practical experience and of more mature wisdom than myself; I have also talked them over with various members of the undergraduate body, for whose opinions I have respect. Some will doubtless be discarded as without value; others will appear too impractical and visionary; there may be a suggestion or two which will bear consideration. If that is so, my aim has been accomplished and I am more than satisfied. Some changes would seem practical in the immediate future; others are large scale projects which can develop only with increase in college funds and gradual development of the educational policy as a whole.

Let us first examine a few recommendations for the near future. It seems that freshman year would be made more profitable were it possible to put into operation a system of individual faculty advisors, who come into contact at least twice during the first two weeks of college with their advisees. The problem is to find men who are competent to handle such an important job of orientation. One possible solution would consist in having the members of the faculty of the course in Industrial Society act as just such an advisory group for half the entering class, and the faculty which is presenting the course in Evolution doing the same for the other half.

If the freshmen were called to college three days earlier than is now the case, and the first week of organized classwork were eliminated in these two courses and devoted to individual conference, these interviews could be efficiently handled. With the cooperation of the office of the Dean of Freshmen, each advisor would have information available about his men, so that he could be of intelligent aid to them. Inasmuch as these two courses are conducted for the purpose of giving a background of knowledge by discussion and work in small sections wherever possible, and for stimulating the dormant intellectual interests of the men, it would seem logical to choose these men as advisors; they are in constant touch with the needs of the entering men, and have more opportunity for personal contact than is the case in other departments.

Again, the placement tests which the freshmen take should allow a choice of a top section in the course, an advanced course in the same subject, or a substitute course, as the reward for high achievement.

Large courses with a tremendous amount of formal lecturing, such as Evolution, should endeavor to give more time to personal conference and discussion, and less time to quizzing on assigned sections, and recitation in parrot-like form.

In the freshman English course, it would seem advisable to expand the system of frequent individual conference which is already doing such good work, and to place less emphasis on the technique and processes of English, and more on the real substance of the course. One cannot write well unless he has something to say; accordingly, one might suggest that the weekly themes be made to deal with matters that will require real thought. It might be profitable to attempt a correlation with the courses of Industrial Society and Evolution, by having the man write thoughtfully on the problems he finds rising to his mind through his study in these courses. Ruskin said that "great writing is the careful expression of right thought," and his idea would seem worthy of consideration for the compulsory freshman English course.

The examinations at the end of each semester of Freshman year might well be made less a matter of mere memory and more a subject for thought and mastery of the ideas in their relation to each other. It is certainly true that the discipline of rigid habits of industry and of concentration is necessary during the year; no one would deny that. However, the ends of discipline would be attained just as satisfactorily by the use of quizzes and examinations which required not merely a grasp of the facts involved, but also a necessity of going one step further and thinking about these facts, which otherwise are merely so many inert ideas.

Greater use of the problem method of approach in the survey courses, more small conference sections and discussion groups, and more attempts to elevate applied thought to a higher plane than that of pure memory would stimulate the intellectual interest which is so essential for successful college work. Notable changes are already made which provide for greater freedom in the choice of freshman courses.

In sophomore year, there is an apparent need for vitalizing the elementary courses in social science, in giving them a vivid relation to actual life. More frequent use of the problem method as an approach to the subject, and an effort to make the examination show a real grasp of the field and its relation to other branches of knowledge would be helpful. In large courses, sectioning according to ability would also mean a great deal. If the freshman year has done its job properly and well, there would be no need to mention the "sophomore slump"; unfortunately, we cannot assume such a degree of practical perfection. More work of an advisory nature during the early part of sophomore year should not only ascertain a man's interests more surely and enable him to choose his major study more wisely at the end of the year, but would also greatly reduce the period of malingering in the later stages of this pernicious and widely prevalent disease.

Upon the beginning of the major study in junior year, it would seem wise that the number of courses for both junior and senior years be reduced to four; a more thorough knowledge of the major study will result from this system, so that one's education can not possibly become "a patchwork of snippets and half measures." This would probably mean the elimination of the complementary course of junior year and the coordinating course of senior year. The disadvantages resulting from such a reduction would be cared for by more careful supervision of program by the departments themselves, whereby they might attempt to cover slightly less ground, but at the same time make a more thorough study of a smaller field. With a smaller unit of work to be covered, more time could be applied to stressing background study, the relation of the subject to other fields of knowledge, and to a more definite integration of the major field as a whole.

More thoroughness appears to be a crying need at the present time. To further this development of the major, a board or a director is needed to supervise the major work in all departments; a man of vision and ability at the head of such a board could bring to bear a tremendous broadening influence in providing for more closely integrated work, and in overcoming the evils of departmental barriers.

Also, in relation to the Honors courses in the major study, one cannot help but think that better results would be obtained were every department to have a staff of men who did nothing but Honors work during the year; the staff could be varied from year to year on some sort of staggered rotation plan.

More general changes that suggest themselves are an increase in the use of small preceptorial groups in all courses, an extension of the use of the individual conference as a means of promoting thoughtful interest, and a more general effort to make the relationship between instructor and student more personal. Quizzes and hour exams certainly have their place in the educational system, and are valuable as a means for discipline, which is essential to any educational plan, but it might be well to reduce the number of them; they have a tendency to make for a superficiality of thought, and they over-value the powers of memory. If some exams seem necessary, as they will, it is logical to make them require as much independent thought as possible.

The fine work that the intramural department is doing in regard to an "Athletics for All" program at Dartmouth should be encouraged in every way possible.

IX

IT is far more difficult to foresee what changes should be made in the future than to discourse on those that seem essential at the present. However, there are several changes that would seem of value for the later development of the College.

First, I should recommend the use of the tutorial system of individual guidance in the major study for eachand every man. It might be possible to start with small preceptorial groups, and work gradually toward the plan, but from observation of its operation at Harvard, it would seem highly practical if applied in this restricted way.

Second, I should like to see a system of achievement tests placed in the College, so that a man might progress to more advanced fields as soon as he displays an adequate knowledge of the elementary work. Third, I should like to advance a plea for a real reading period each semester, of about two weeks in length, where every man in the college would have certain assigned reading to do and for which he would be held responsible in the examinations; this would give every man an opportunity for work of truly independent nature.

Fourth, I hope to see a divorce between the function of instruction and the function of marking and creditawarding. An external examination system would not be the solution, but a board of examiners composed of men from the department, and men from other fields of an allied nature, might meet the problem satisfactorily. Like the comprehensive examination this would tend to raise the general tone of instruction by bringing home to the instructors the necessity for broad and thorough work, and would aid in bringing departments in closer touch with one another.

These are specific and small-scale projects; I have in mind one large-scale plan, which is, and has been, in the minds of the College authorities for some time, but lacks the necessary funds for its completion; I am referring to the necessity for a building devoted to the social uses of all classes. It should contain adequate dining facilities, game rooms, a comfortable library, and social rooms for conversation, music, and general conviviality. An adjoining Graduate Club for the residence of instructors and a theater and convocation hall should be a part of this new unit. As Baker Library is the intellectual center of the College so should there be a Student Union as the social center. There is a great need for such an institution in the lives of freshmen, sophomores, juniors, seniors, and the faculty at Dartmouth, and it is my hope that this may be realized in the near future. It is the greatest single need of the College today.

X

WE have seen the set-up of the curriculum at Dartmouth; I have tried to give rome of my ideas on the advantages and possible improvements in the Dartmouth system. It only remains to check up on the correlation between our ideal and our actual college. Viewed objectively, it is impossible for me to make this comparison with any pretense at accuracy; there are too many intangible factors which enter into the picture. I am going to try and effect my comparison subjectively, and leave the cold, hard facts exactly as I have stated them, where anyone who so desires may correlate to his heart's content. Dr. Aydelotte once said that the curse of the American college was its Religion of Punch; by that he meant the form of charlatanism, of bluffing raised to a higher order, which has the ability to achieve the end without the means, the whole without the part; "it makes railways without money, churches without religion, literature without art, newspapers without news, and educational institutions without educated men."

In no other college have I seen so little of this actual Religion of Punch as in Dartmouth; time and time again I have heard people say that they found the average Dartmouth graduate possessed of an openmindedness and receptivity to new ideas that were lacking in the men from other colleges. One may say without prejudice and without conceit, that Dartmouth's present educational policy is progressive in the best meaning of the word. The vision and foresight of President Hopkins, and the sympathetic cooperation of his trustees and faculty members, have given Dartmouth a curriculum which teaches the ability to think for one's self, and which aids its alumni in so developing that the totality of their lives may become a thing of beauty, that their social consciousness will inspire more responsible leadership and more intelligent citizenship.

HOWLAND H. SARGEANT '32 Senior Fellow and Rhodes Scholar-Elect. Author of "An Undergraduate Looks at His College"

JOHN McLANE CLARK '32 Senior Fellow, editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth, editorial contributor to this number of THE MAGAZINE

E. F. CARTER '32 Author of "Recommended: A Trip to Mexico" in this issue

W. H. FERRY '32 Monthly contributor to the MAGAZINE of the "Undergraduate Chair"

A student committee headed by W. H.Cowley was appointed by PresidentHopkins in 19 and ashed by him to scrutinize carefully the curriculum of the timeand to report its findings. The UNDERGRADUATE REPORT OF 1924 has become aclassic in the published material dealingwith Dartmouth's curriculum. With theexception of Prof. L. B. Richardson's STUDY OF THE LIBERAL COLLEGE no Dartmouth publication treating this subject hasbeen more influential or widely read.

In the eight years elapsing since 1924 nocomprehensive survey of the curriculum hasbeen made by an undergraduate. For nearlythree months Howland H. Sargeant of thesenior class has been at work on the articlehere presented as the feature of the maga UNDERGRADUATE NUMBER. Asa senior fellow he has been free to devote allof his time to reading, interviews, and tripsto other colleges in the process of gatheringmaterial for this interesting paper addressedto alumni, faculty, and his own college generation. It is the third distinctive contribution to the record of Dartmouth's curriculargrowth. And it is the latest and one of themost authoritative of the expressions of student opinion on the academic present andfuture of the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article"Wildcatter"—A Play in One Act

April 1932 By James W. Riley '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1928

April 1932 By Leroy C. Milliken -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

April 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Article

ArticleThe Value of Fraternities to the College

April 1932 By Robert Coltman '32 -

Article

ArticleRecommended: A Trip to Mexico

April 1932 By Bud Carter '32

Howland H. Sargeant '32

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Dinners

May 1944 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

March 1960 -

Article

ArticleNEWS IN BRIEF

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

December 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleRICHARD EBERHART: A Reader of the Spirit

June 1952 By JOHN W. FINCH -

Article

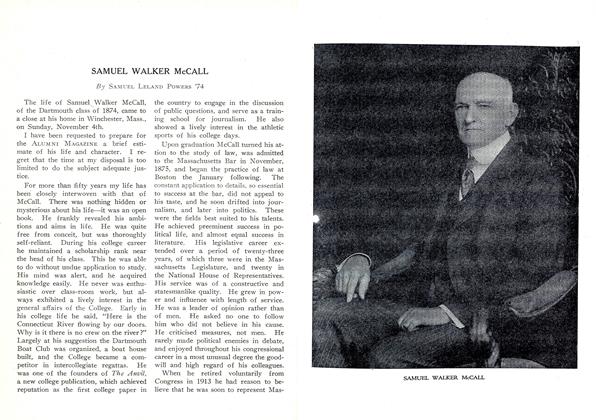

ArticleSAMUEL WALKER McCALL

December, 1923 By SAMUEL LELAND POWERS '74