No existing institution can be intelligently understood or reasonably criticized without an examination of its history and a survey of the needs which prompted the various stages of its development. Nor is it of any significance to uproot an institution from the soil which gave it birth, to deprive it of its social backgrounds, to isolate it in time and space, in discussing such a subject.

It would be difficult to find a thinking man who, in a cool moment, would deny the validity of these statements, and yet I have never heard a discussion of any of the aspects of the American fraternity system that did not do these things. Without going into the causes, it is self-evident that the subject of fraternities has in common with the subjects of marriage and religion the inherent quality of stirring up intensely partisan feeling on the part of those who consider them. Such an attitude tends to foster the "all or none" principle, which is the antithesis of a reasoned, critical attitude; it tends to encourage opinionated obstinacy; it tends to think almost entirely in terms of propaganda. It is high time that all of those concerned with the matter of fraternities in the colleges of this country renounced the shallow emotionalism that has characterized most of the commentary upon the problem in favor of the common sense examination that it deserves. I am more anxious to have this method of approach to the problem become general than I am to express my own conclusions on the subject and I shall present here only the condensation of a few thoughts on the subject merely as a starting point for other consideration of it.

As Dr. Henry Suzzallo, of the Carnegie Foundation, recently pointed out, "If you go to the Continent of Europe, about the only question that is asked by the university authorities is, 'Can you pass your examinations?' Student health and student morals are the student's own business, and there is no particular attempt made to look out for the aspects of personality which are not intellectual." While this is certainly not true of the traditional English educational system, the early American colleges and universities seem to have copied more from those of the Continent than from those of the Island Empire in this respect.

GROWTH OF COLLEGE CLUBS

It is not in the least surprising that in these male scholastic colonies of the post-revolutionary period social groups, clubs, associations, fraternities began to be formed; the instinct to form such groups for mutual benefit antedates the Stone Age, and still has its usefulness when not carried beyond the willingness to cooperate, as has been the case, for example, with the arrogant and belligerent institution of nationalism. We may assume that such a need was very real, for the rapid growth of size and power of college fraternities in this country is little short of amazing. The healthy thing about this movement is that it sprang from the students themselves, and represented something that they wanted from education and found lacking in the system that attempted to give it to them. Even if a few of the groups so formed did tend to become subversive to the best interests of the educational process their interested, active concern for the education they were getting seems more commendable than the insipid attitude of milking Alma Mater and receiving a meaningless sheepskin for stupid conformity which pertains in many a college today.

These were frontier youth that were interested in the sort of man they were going to be when they got through with the college process, and the frontier tradition has one strong point in its hatred of passivity. English youth, on the other hand, steeped in the worship of tradition and authority waited for the gods of their educational firmament to answer their needs. And the gods served up the rudiments of what has come to be known in this country as the House Plan. No doubt this system has worked well, in many cases better than our own fraternity system, but it was born of the benevolent paternalism of academic faculties and not of the active participation in student life of students themselves.

FAILURE OF FRATERNITIES

There are tremendous values inherent in the approach to education of early American student bodies. I believe that in the majority of cases the American fraternities have failed in their job. They too have become placid, passive, and have failed to keep the active movement which their predecessors started in touch with the reality of their contemporary needs. They have stagnated and become encrusted with a habit of mind which is now antiquated and useless to their present situation. They are in many instances failing the need of their members, and in this failure lies the peril of their extinction.

The symptoms of this are already evident. Some of the largest and most influential institutions of learning in the country have started to ape their English cousins in setting up residential colleges which are modelled on the principle of those across the sea. I am not opposed to aping something that is really worthwhile, particularly if there is no other way to serve the need. But I am firmly convinced that the aping in this case is largely due to the decay of the most valuable attribute of a university—that of student interest in its own welfare; and also I think it is due to a widespread tendency to ape everything European from architecture to hors d'oeuvres with a servility which is decadent to say the least. To pervert the noble lines of Macbeth: If we fail —we fail, but if our courage and our interest is a little more than that of a suckling child we will not fail to take an institution that is indigenous to our own academic soil, our own need, and answer the challenge which changing conditions present in ever-increasing insistence.

In each, college or university the situation is just a bit different. I will not try to answer the needs-of any other than our own institution. Dartmouth finds itself among a group which have come to be called liberal colleges. In fact Dartmouth is in many quarters recognized as preeminent in this type. If fraternities on the Dartmouth campus are to be of value they must serve the major .objectives of the larger institution of which they are a part.

The main objective of Dartmouth as a liberal college is, as I see it, to arouse and stimulate the process of thinking in the minds of its undergraduate body by means of enlarging and broadening the minds of its students to their utmost possibilities—especially in regard to their capacity to think. In the pursuance of this aim the ideal of the well-rounded and full man is absolutely essential.

The reason for the inclusion of the conception of the well-rounded man in the primary objective of the College is that the ultimate duty of education, if it is to justify itself pragmatically, is to fit men for life. More today than ever before there is a crying need for education which will produce the well-rounded man—the man oriented in time and space, the man who understands the changing conditions about him, the man who can live fully and intensely for himself, and serviceably to the society of mankind about him.

THE PLACE OF THE FRATERNITY

Where does the fraternity fit into this scheme of things? I think it fits in admirably with the major aim of the College—at least it could. In the first place, ideas are born of discussion. The informality and the congeniality of the fraternity group can provide a meeting place for and a stimulation of ideas. It is easy to be cynical about the value of such discussion after sitting in on a typical house bull session, but is it courageous, is it active to look at it that way? One of the most pleasurable experiences in my own fraternity connection has been to watch the development in some men's minds as they have gone through the process, and gained the ability to think clearly and to state their thoughts comprehensively, as much I think through the long procession of bull sessions as through the advice meted out in the classroom.

In the second place the skepticism which is likely to be found ever present in such collegiate groups is likely to challenge and correct the stodgy conservatism that sometimes creeps into corners of faculties of professional, academic teachers. Then too there is a tendency for the influence of the fraternity group to run to worldliness and up-to-dateness which presents the problem to the individual of seeing his own contemporaries and the lives they are leading in the light of the wisdom of past generations.

The fraternity house provides still another utility of value to the College. In the genial informality of its comfortable rooms it provides a neutral meeting ground for members of the faculty and the undergraduate body. Here the decorous formality which has its values in the classroom may be cast aside, and students may gain still other values that cannot be had without the help of an open fire and quiet comfort. Many houses have taken advantage of this opportunity, and I hope that the custom will grow, in strength and usefulness.

There is another way in which the fraternities may serve to augment the efforts of the College. In order to attain the main objective of the liberal college diverse and controversial points of view should be presented, in order that the student may gain judgment in weighing the comparative merit of material that is offered. Equally essential in the furthering of this aim is insistence that freedom of thought and of speech be allowed and encouraged on the part of the student body. There is no place like one's fraternity in which these divergent views may come spontaneously to the sur- face, and although they are often ill-informed, still the exercise of one's faculties in this direction serves as apprenticeship to mature thought.

SELF-DISCIPLINE VALUABLE

The fraternity is apt to foster another quality which is of definite value to the aim of the College. The official college may clamp discipline upon the students from a dozen angles and yet a student may have nothing of the all-important self-discipline which is essential to mature life. The life of a fraternity as a social group demands a certain amount of self-discipline from its members. Some never succeed in gaining it, but those who do owe much to the life to which they have acclimated themselves in the chapter house.

Then too, of course, the fraternity pays a great deal of attention, often admittedly too much, to. the social, superficial if you will, side of student life. This too is part of the well-rounded man, and hence has its value.

I could go on ad nauseum listing the aid which the fraternities have the opportunity to give to the major aim of the College. But their main function lies in rounding up the man—keeping him from being lop-sided. It is almost impossible to belong to any group whatsoever on the campus and not be thrown in contact with widely divergent types of men and widely divergent ideas. And it is significant to note that the houses which are generally acknowledged as campus leaders derive their main strength from a diversity of active men, wellrounded men.

I do not think that I have painted an improbable picture of fraternity life. Perhaps I have painted a picture nearer to what I would like to see than to what it is, but a constructive, optimistic attitude, if it does not lose touch with reality it seems to me is far better than a lethargic, pessimistic one. It is the challenge which I would offer to the fraternities—to measure up, or die.

Fraternities are often referred to as primarily social organizations. This has long been true, but unfortunately in many cases in only the narrowest sense of the term social. If this continues to be the attitude of fraternity men then the net value of the institution is debatable and the Lloyd's rates on their life should be very high indeed. But if the conception of a fraternity that is already making great progress and continues to do so, that of the fraternity as an integral factor in the larger social process of education, then the fraternities are on the threshold of a new period of usefulness and a new era of vitality.

LOW SCHOLARSHIP

There is one obvious respect in which the fraternities have, I think, failed to measure up. The fraternity scholastic average in the past four years at Dartmouth lias varied from one-tenth to two-tenths of a point below the average of non-fraternity men. Considering that the main job of our college life is a scholarly one, and considering that fraternity men have many advantages over non-fraternity men, I see no excuse for their scholastic average remaining below the all-college average, even to this slight degree. There are several houses which offer scholarship prizes, a practice I should like to see all houses follow. Other indications that fraternities are more than organizations merely to facilitate dances are the enthusiastic interest in intramural sports and in such purely cultural activities as the Interfraternity One-Act Play contest.

Such activities, it seems to me, are vastly more important than the mechanics of running their own internal mechanism to which so much time and thought is given. The Interfraternity Council, now made up of the 26 house presidents has this year endeavored to place such matters above the level of hypocrisy, and at the same time to minimize time and money which is usually wasted in the process of perpetuating the various houses. How far such actions will be effective only time will tell.

CONTINUING GROWTH

The important thing to me is that after long consideration of the system and all its obvious evils, and after an earnest talk with the man, who, more than any other, has his heart and soul wrapped up in the values that this college represents I feel that I can say of the individual fraternities on the Dartmouth campus what has been said of the Dartmouth Interfraternity Council: that more essential than the relatively simple matters of administration and routine functions, the houses have this year proved themselves to be key groups on the campus to which widely divergent interests could look for hearty cooperation whenever the matter seemed to the advantage of Dartmouth College. Thus must these organizations continue and not only justify their existence but give answer to those who think that the fraternity system is inconsistent with the ideals of the liberal college.

ROBERT COLTMAN '32 Senior Fellow, president of the Interfraternity Council

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAn Undergraduate Looks at His College

April 1932 By Howland H. Sargeant '32 -

Article

Article"Wildcatter"—A Play in One Act

April 1932 By James W. Riley '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1928

April 1932 By Leroy C. Milliken -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

April 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Article

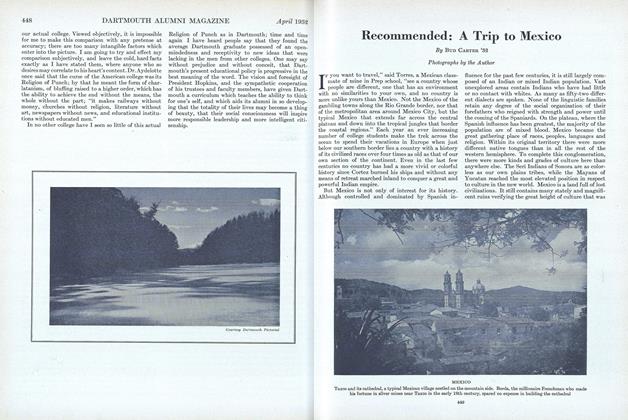

ArticleRecommended: A Trip to Mexico

April 1932 By Bud Carter '32

Article

-

Article

ArticleATHLETIC MEET

OCTOBER, 1906 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Represented at Many Functions

November 1933 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

JANUARY 1964 -

Article

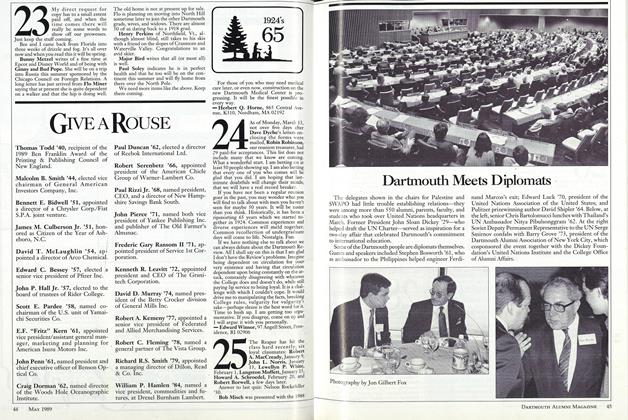

ArticleGive a Rouse

MAY 1989 -

Article

ArticleEquinox: A Poem of the Hanover Fall Season

November 1932 By Pennington Haile -

Article

ArticleLEEDing the Way

July/August 2005 By Sue DuBois '05