Department of Economics, Dartmouth College

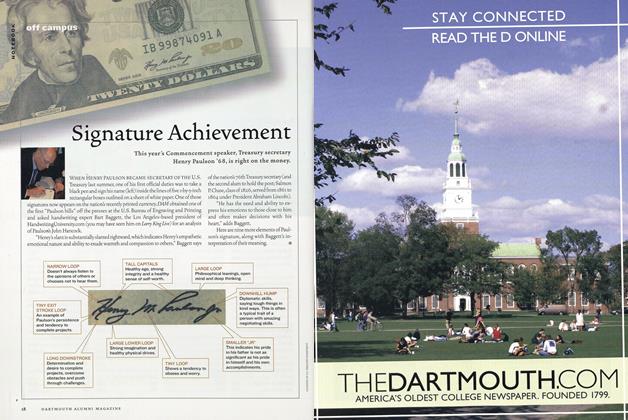

A LITTLE more than a century ago, a leading French economist, J. B. Say, in one of a number of open letters to Malthus made the statement that "I have always found, practically, that new machines produce more alarm than injury." If the Literary Digest were to take a straw vote on this question at the present time it would undoubtedly find opinion widely divided. There would be many who would unhesitatingly affirm that what Say said was correct. And there would be many who with equal readiness would maintain that he was wrong. On what grounds would they base their opinions?

Suppose that we could listen-in on a discussion between a number of pro-Sayers and a number of anti-Savers, what would we be apt to hear? We would certainly hear the pro-Sayers stressing the great improvement that has taken place in the material well-being of humanity. They would show that goods and services which were luxuries to our grandparents, or even to our parents, have become necessaries to us; that goods and services which were not within the reach of the comparatively wealthy a few decades ago, or even known to them, are now enjoyed by millions in the lower income classes. The more intelligent supporters of Say's view would not push this argument too far, however. They would be sure to explain that wealth and welfare are by no means synonomousunless, of course, the term wealth is used in the Ruskinian sense; that the "good life" is not the same as the "goods life." But they would add that wealth in the economic sense contributes to welfare, and that a substantial material foundation is necessary before the good-life superstructure can be built.

And then the pro-Sayers would point to the great reduction that has taken place in the length of the working-day. No longer is it necessary for the bulk of mankind—at least for that part of it living in Western Nations—to work sixty or more hours a week. Those of the group who had read some of the popular literature on the subject would undoubtedly be conversant with Stuart Chase's statement that we are still working harder and longer hours than was customary in many former societies. But this fact would not invalidate the general conclusion that during the last century and a half there has been a great reduction in the length of the working- day.

The more sensitive members of the proSay group would perhaps feel a little uncomfortable when in the midst of this argument some member of the anti-Say persuasion sarcastically remarked that the length of the working-day certainly has been reduced—in fact at the present time it has been reduced to zero for many workers and to an uncomfortably low level for many more. The stronger supporters of the Say view, however, would take pains to point out the desirability of distinguishing between the temporary and the permanent, the direct and the indirect, the concentrated and the diffused, having in mind, perhaps, the useful lesson that Bastiat taught about the Seen and the Unseen. They would go on to affirm that the movement in the direction of shorter hours would continue in the future. Those of their number who had carefully studied the problem of unemployment would hasten to add, however, that the continual reduction in the length of the working-day would not of itself solve the unemployment problem.

The anti-Sayers would not be without strong arguments to support their position. They would emphasize the large amount of unemployment that mechanical progress causes. Some of the more enthusiastic members would likely ascribe the present depression wholly or chiefly to the rapid technological advancement of recent years. They would perhaps tell about the brick-making machine in Chicago which can turn out 40,000 bricks an hourit formerly took one man eight hours to make 450. They would likely refer to the steel industry where, in casting pig iron, seven men now do the work which formerly required 60; where two men now do as much as 128 in loading pig iron; where one man replaces 42 in operating open- hearth furnaces. With such examples of recent mechanical changes in mind, and with vivid recollections of statements (made by writers on Technocracy) about the razor blade that will last more than a lifetime and the rayon factory that will be operated by one man at a switchboard, some would undoubtedly agree with the assertion made in the November 1931 issue of Harper's that "Our machines and our science of management have made us so efficient that there is no longer enough work to go around." The more curious of the pro-Sayers would certainly ask why we have just discovered this fact when our machinery and our science of management have been undergoing marked changes for a century and more. And those concerned about the future, and who had read Henry Ford's statement that we are not beyond the creeping stage in business—the events of the last few years have added poignancy to his remark —would likely wonder whether, a hundred years from now, one sixtieth or one seventieth of those able and willing to work will be able to obtain employment, in view of the fact that already there are no longer enough jobs to go around.

All the anti-Sayers, however, would not believe in any permanent shortage of work due to the increasing use of machinery. They would realize that a permanent shortage of jobs is out of the question, perhaps having in mind Arthur Salter's statement that "human demand is illimitable and will be until the last Hottentot lives like a millionaire." Someone would perhaps ask, why stop at the millionaire? And a few in the group would likely realize that even if we did reach a point where all our wants were satisfied there is no reason for believing that we would then have a permanent shortage of jobs.

Even among those of the anti-Sayers who admitted the indefinite expansibility of human wants and the impossibility of a permanent shortage of jobs, there would be some who would maintain that the short run effects of technological change on the employment of labor are sufficiently serious to constitute a good cause for alarm. They would have statistical evidence to prove that many workers who have been displaced by machinery have not been immediately re-absorbed into other jobs. And to add still greater strength to their case they would mention the large number of accidents that happen each year in our industrial establishments. But the indictment would not stop at this point. Some of the members of the anti-Say group would go farther and launch an attack on machine production in general, stressing the deleterious effect it has on the personality of the workers. To their assistance they would bring the opinions of some of the great men of the ages. Undoubtedly Karl Marx would be one of those giving evidence. "Manufacture," said Marx, "seizes labor-power by its very roots. It converts the laborer into a crippled monstrosity, by forcing his detail dexterity at the expense of a world of productive capabilities and instincts; just as in the States of La Plata they butcher a whole beast for the sake of his hide and tallow." The authority of Ruskin would also be brought to bear upon this question. On the matter of division of labor, which is closely associated with machine production, though by no means synonomous with it, Ruskin affirmed that "It is not the labor that is divided, but the men—divided into mere segments of men, broken into small fragments and crumbs of life." Elaborating on this point, some would advocate, along with Prince Kropotkin, not the division of labor, but the integration of labor.

The pro-Sayers would admit that the division of labor has certain disadvantages, but they would point out that our material welfare is dependent upon a wide application of the division-of-labor principle; and that if each individual tried to build his own furniture, sole his own shoes, grow his own vegetables, and make his own mouse-traps the world would not make a beaten path to his door; he would not enjoy commodities brought from afar; he would not have a high standard of living. His life would be solitary and poor; and possibly nasty, brutish, and short as well. He would, it is true, have adequate employment. He could work 20 hours a day and more, and yet not be able to produce enough to enable him to keep much above the starvation level. If the problem were simply and solely one of providing employment, it could be very easily solved. But it is much more than that.

The supporters of the Say-view would, again, deny that machinery has made life more monotonous; and to lend authority to their opinion they would perhaps quote Bertrand Russell. "The machine age," says Russell, "has enormously diminished the sum of boredom in the world." All those participating in the discussion would likely agree that much of the work done for wages at the present time is monotonous in nature. Some of the pro-Sayers would undoubtedly go farther and declare that many individuals seem to delight in such work as it relieves them from the necessity of assuming responsibility; and there is a remote possibility that one of their number would mention the significant point made by the German economist Roscher that it is monotony of life much more than monotony of work that is to be dreaded: the latter is an evil of the first order only when it involves monotony of life.

This heavy verbal attack would perhaps cause a little confusion among those who denied the validity of Say's remark. But some of their number would soon recover themselves and say that machinery has made life monotonous. Opinion on this point would obviously be divided, and perhaps it would be best for us to leave the disputants argue it out amongst them- selves—knowing that they will not reach any unanimous decision—and turn to a more scientific analysis of the topic announced.

It will be impossible to discuss all the points raised by the straw voters, but there are three that are especially worthy of additional consideration as well as another one that was not touched on. The first relates to the standard of living; the second to the length of the working-day; the third to technological unemployment; and the last to means for dealing with some of the unfavorable consequences of mechanical progress.

II

WHILE AVE STILL have a great deal of abject poverty—the amount of it increasing whenever we pass through the depression phase of the business cycle- there can be no doubt that there has been a raising of living standards for a very large percentage of the population during the past century. While it may be true that the rich have grown richer and poor poorer, if we think in relative terms, it is undeniably true that in absolute terms both the rich and the bulk of the poor have grown richer.

Our standards of living are not as high as they would have been had the length of the working-day not been reduced, however. The benefits of mechanical progress have been taken partly in the form of more goods and services and partly in the form of a shorter working-day. Had the former not changed, the latter—that is, the length of the working-day—could have been decreased still more. Were we to be content with the standards of living that our grandparents had we could al- ready have a work-day whose duration would border on the Utopian.

In fact, even with the high standards that we already enjoy, we could still have a shorter working-day if we made the best use of the productive resources and equipment that we have at our disposal. But for various reasons, such as the periodic dislocation of business; the "conscientious withdrawal of efficiency," which, according to Veblen, "is the beginning of wisdom in all sound work-day business enterprise that has to do with industry;" the wasteful use of human labor; and the restriction of output on the part of the worker, caused largely by fear of unemployment—for reasons such as these we fail miserably in making use of our productive powers.

In connection with any discussion of the standard of living, it should be borne in mind that what we consume is dependent upon what we produce. A very elementary truth this is, to be sure. Yet it is a truth that seems to be overlooked at times. Those who advocate a permanent reduction in the length of the working-day as a means for dealing with unemployment are particularly apt to overlook it. In the absence of a re-distribution of wealth brought about by some such means as the use of the taxing power, the standards of living are likely to go down if the reduction in hours is not accompanied by an increase in the productivity of labor—and this does not mean productivity per hour, but productivity per week, or, even better, productivity per lifetime. This is one of the reasons why the spreading of work is at best a temporary expedient.

Another point to be borne in mind is that the standards of living will not likely be raised very much by inducing or compelling all employers to maintain wage rates during a time of falling prices. This statement is not made with the intention of discrediting high wages. It is not based on a belief in the old doctrine of the utility of poverty, classically stated by Arthur Young. High wages constitute a very worthy social objective, but it should be recognized that there are sound ways and unsound ways of achieving this objective. Certain policies which, superficially, seem very desirable may have undesirable, and frequently unforseen, consequences. It is possible that if wages are arbitrarily held at a high level they may have such results.

If wages are held above the value productivity of labor—and the latter falls during a time of rapidly declining prices-a policy of wage maintenance may mean an increase in unemployment and a prolongation of the depression. Such men as Beveridge, Pigou, and Keynes are inclined to believe that the severe chronic unemployment in England during the post- war years was due in no small measure to a situation of this nature.

There are numerous ways in which to increase the productivity of labor—or more accurately, the marginal productivity of labor—one of them being to decrease the number of laborers. There is danger, therefore, that when wages are for one reason or another kept above the marginal productivity of labor that the employers will increase the latter by decreasing the number of laborers employed. In other words, wages may be maintained for some workers, but at the expense of employment for others.

This question of wage rates and employment is a large one and there is not sufficient time to discuss its various ramifications. Most professional economists would undoubtedly agree, however, with the following general conclusions:

1. Labor may not be receiving a wage equivalent to its productivity and consequently it may be possible in such instances to bring the two into line by attempting to maintain wage rates during a time of declining prices.

2. There is the danger, however, that wages may be maintained at a level that is too high—and here I am not speaking in any ethical sense—and so may cause unemployment.

3. The argument concerning the maintenance of purchasing power by keeping up wage rates is to a large degree fallacious. Such a policy to a great extent results in a transfer of purchasing power rather than in an actual increase in purchasing power. It may not always have this result, however.

4. If wages and other more or less inflexible prices, such as rents, certain interest charges, etc., could be adjusted more rapidly to changes in the commodity price level, depressions would not be as long as they are, nor as serious. This does not mean that wages should be slashed indiscriminately when prices fall. But a more rapid adjustment would be desirable; not only, of course, when prices are falling, but also when they are rising. Such adjustments would involve an increase in real wages over long periods—if the hours of work were not decreased too rapidly—in accorda nce with the increasing productivity of labor.

Such adjustments would be unnecessary, or largely so, if we could make the present flexible prices, especially commodity prices, more inflexible; that is, if we could stabilize them. If we could succeed in doing that, our complicated system of prices would not be thrown out of balance periodically the way it is at the present time; and disputes over wage reductions would either not arise or not be as serious as they are under present conditions.

Before leaving this question of mechanical progress and the standard of living, there is one other point that should be noted. It is this: We cannot have high living standards—that is the present popu-lation of the world cannot—and at the same time use crude methods of production. Anti-machine-agists are sometimes inclined to overlook this fact.

William Morris apparently was guilty of such an oversight. Graham Wallas tells of a rough calculation he once made when listening to Morris lecture in which he discovered that the citizens of the commonwealth Morris was advocating would find it necessary to work about two hundred hours a week if they were to produce, by the methods that Morris suggested, all the beautiful and delicious things they were to enjoy. That "happy and lovely folk who had cast away riches and attained to wealth," about whom Morris tells us in his delightful book News fromNowhere, were supposed to have lived a life of "repose amidst energy." But surely they could not have had much repose, or else they must have been possessed of terrific energy.

III lET us NOW turn to the question o£ hours. There can, of course, be no dispute as to the reality of the reduction in the length of the working-day. Nor can there be any dispute as to the likelihood of further reductions in the future. Undoubtedly we shall attain, and in some cases surpass, the work-day standards set up by the Utopians. The increasing use of machinery will largely make this possible.

Along with the actual reduction in the length of the working-day there has been a considerable amount of speculation as to what it might be. Speculation of this nature has been especially common in recent years; but in surveying it, let us go back several centuries, and in a few long and rapid strides come down to the present.

Campanella in his imaginative "City of the Sun" established a short working- day of about four hours. This was made possible, not through the extensive use of complex mechanical tools and devices, scientific management, and large scale production, but through compulsory labor. As Campanella expresses it, "while duty and work is distributed among all, it falls to each one to work only about four hours every day."

Sir Thomas More established a six-hour working-day for the subjects of King Utopus. This was brought about by compelling almost all the inhabitants, men as well as women, to engage in work, and by having their efforts devoted to the production of necessaries.

The "First Civilized American," in his letter of July 26, 1784, to Benjamin Vaughan, explained the presence of so much want and misery in the world at that time as due to the employment of men and women at work that did not produce the necessaries and conveniences of life, and to the fact that these individuals, along with those who did nothing, consumed the necessaries raised by the laborious. Franklin mentions the computation of a political arithmetician who estimated that if every man and woman would work on something useful for four hours each day, enough would be produced to procure all the comforts and necessaries of life. The remainder of the day might be used for leisure and pleasure. Misery and want would be banished from the world.

Perhaps the most startling estimate that anyone has ever made is Godwin's. In the eighth book of his "Enquiry Concerning Political Justice," Godwin endeavors to convince his readers that if property were equally divided, and if all the members of the community were to be seriously employed at manual work for half anhour a day, the necessaries for the whole community would be supplied.

Professor Julian Huxley, one of the long list of modern prophets, and honored both in his own and other countries, predicted a year or two ago, a two-day working week.

And so one could go on mentioning calculations of this sort, but it will not be necessary. From what has been accomplished in recent decades in shortening the length of the working-day, it is evident that none of these estimates, save, possibly, Godwin's, is so fantastic as to be justly deemed an absurd impossibility. Undoubtedly the time will come when the regular working-day, or working-week, will be much shorter than it is at the present time. The technological and economic forces that are bringing us towards the situation that Professor Huxley and others have mentioned are in operation, even during the present period of acute unemployment; and they will continue to be at work after business has revived.

In fact, Mr. Parrish, one of the "unofficial" spokesmen of Technocracy, informs us, possibly with some exaggeration, that "Technocracy tells us that with what is known now about the application of technology, the adult population of this country would have to work only four hours a day for four days a week to supply us with all our material needs."

While the length of the working-day will be greatly reduced in the future, there is no reason whatever for believing that the unemployment problem will be solved through such a reduction. We can have as serious an unemployment situation when the length of the working day is four hours as when it is eight hours, a fact which many individuals seem completely to overlook.

It would seem that Walter Teagle, president of the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, and at present actively engaged in directing the Share-the-Work Movement has erred in this respect. Mr. Teagle said, according to a recent interview granted to S. J. Woolf, that "if the twelve-hour day of the 1880's had been in force in 1938, 40 per cent of our workmen would have been without jobs, and instead of a period of prosperity we would have been in much the same situation that we are today." If this conclusion is correct, then one is justified in asking, "would 80 per cent of our workers have been without employment if the length of the working day had been 16 hours; and 99.8 per cent if it had been 20 hours?" Mr. Teagle's statement is, of course, fallacious.

What would have been the result had we had the twelve-hour day of the eighties in force in 1928? There would have been many. One of the most important would have been a material standard of living much higher than we actually had. But there is no sound reason for believing that the volume of unemployment would have been much, if any, greater. To say that 40 per cent of our workmen would have been out of jobs is naive, amusing, and nonsensical.

A statement similar in vein to Mr. Teagle's was recently made by President Green of the American Federation of Labor. The Federation at its recent convention adopted a report made by a Committee on the Shorter-Work-Period. Mr. Green in advocating the adoption of the report said that under present conditions it was impossible to provide employment for the entire working-population on the basis of an eight-hour day six days a week. "Are we going to resign ourselves to an economic situation where eleven to fifteen million men are to be continually idle?" he asked. While favoring the end that Mr. Green is advocating—that is, the shorter worßing day—l cannot endorse the logic he is using in an effort to attain it.

President Green apparently believes that there is no longer enough work to go around; hence the desirability of a shorter work-week. It is the old story of believing in what is called in economic parlance a "fixed work-fund."

This is one of the commonest of popular fallacies. Many people believe, or seem to believe, that there is just a certain amount of work to be done; and that if the work is, to an increasing extent, taken out of the hands of man and turned over to machines the spectre of unemployment will keep on growing in size—unless the magic incantation of shorter hours is chanted. An understanding of a modernized version of what is known as Say's law would dispel the apparition. According to Say there cannot be any such thing as general overproduction, because the supply of goods is the demand for goods. This is clearly seen in a barter economy. Two observations concerning the "law" as applied to the present time are in order, however. In the first place, the law is a long-run proposition. It must inevitably be so in a money and credit economy such as ours. And in the second place, it is possible to have general over-production in the sense that more goods are produced than can be sold at the prices the producers want for them. The fundamental error in Mr. Teagle's and Mr. Green's statements can be seen when we realize that the total amount of work that could be done has no fixed upper limit.

Unemployment will not be cured through reducing or limiting the amount of production by cutting down the length of the working-day. As a matter of fact, compulsory limitation of hours may in some instances actually increase unemployment, especially if an attempt is made to maintain wage rates. Some employers would use even more machinery than they are now using, and as a consequence the amount of technological unemployment would be increased.

If production could be regulated, if its growth could be regularized—and this need not mean, and should not mean, a net decrease in its amount—the volume of unemployment would be greatly decreased. Not only would the amount of unemployment due to technological changes be cut down, but that due to cyclical downswings in business would also be greatly reduced. Such regulation, however, will involve a narrowing of the charmed circle of private industry. It will not be achieved by reducing hours.

But let us return once more to President Teagle. Is he simply wasting his time by advocating the spreading of work as a means for dealing with unemployment? Not at all. As a temporary measure reducing the length of the working-day has much to commend it. It results in many workers being tolerably well fed rather than some having more than they require to satisfy their physical needs and others having less; it tends to allay discontent and unrest; it helps to preserve the skill of the workers which, in a time of protracted idleness, may be impaired. According to a recent statement of Mr. Teagle, sponsors of the Share-the-Work movement have never claimed that they are doing something of permanent value. This is the sensible attitude to take, but it is difficult to see how it can be Mr. Teagle's attitude, in view of the earlier statement he made to S. J. Woolf, and which we have quoted. Perhaps he has changed his mind on the matter since the time of the interview.

The policy of spreading work decreases the amount of unemployment; but it increases the amount of under-employment. And in this connection it should be noted that work should not be divided—and this Mr. Teagle recognizes—if it means that the individual who is sharing the work with someone else is exposed to physical suffering. Yet this seems in some instances to have happened. Social workers have at times referred to the policy not as "spreading work" but "spreading misery."

IV WHILE THOROUGHLY disbelieving that we are going to have a permanent shortage of jobs, becoming more serious as the years go on, I believe that we shall always have some unemployment resulting from technological changes. But the volume of such unemployment will vary from time to time. In the long run—a term frequently misunderstood and some times ridiculed—the bulk of the displaced workers will be re-employed. Some of the older ones, it is true, will likely be unable to get back into steady employment. But it will be age discrimination rather than a permanent shortage of jobs that will keep them in enforced idleness.

Most economists, at least of those who have seriously thought about the matter, disbelieve that technological changes result in a permanent shortage of jobs. Their reasoning is of the following character. Assume there is a technological change in a given plant or industry. As a result, money costs of production are decreased. Prices may or may not be reduced as a consequence. If they are reduced, more units of the article produced will be purchased. The total amount spent on the article at the lower price may be less than, the same as, or more than before, depending on whether the demand for the article is inelastic, has an elasticity equal to unity, or is elastic. The amount of labor displacement, if there is any, depends in part on the nature of the demand for the article. If at the lower price there should not be a very big increase in the number of units purchased —in other words, if the demand is inelastic in nature—the displacement will tend to be large. If, on the other hand, there should be a large increase in the number of units taken at the lower price, the displacement would be small. In fact, it is possible that instead of displacement there may be an actual addition to the working force.

If the prices are not reduced, profits will be higher. And what will the profit receivers do with their increased earnings? They will spend them for consumers' or producers' goods and services, thus providing additional employment opportunities; or they will directly or indirectly invest them in other enterprises, or re-invest them in their own, which will also give rise to employment; or they will deposit them in a bank. In the last case, the banks will, if possible and profitable, use them as a basis for extending loans to business men and private individuals, and these loans are put to uses which involve the employment of labor. Of course, the funds deposited in banks are not always put to such a use. At the present time the banks have ample loaning power but private business men are not taking advantage of it, largely because they are uncertain as to future business conditions. In less depressed times, however, the banks not only expect to, but do, use the funds placed at their disposal, though not up to the limit at all times.

Perhaps someone will say that even though the price of the article produced by the new or improved machinery should fall, the number of units taken at the lower price would not increase because what the present employed persons gain in purchasing power as a result of the lower price would be offset by the loss of purchasing power on the part of the displaced workers. This argument is not without a little merit, but it is not sufficient to enable one to make any generalization to the effect that the number of displaced workers will constantly keep on increasing. The loss of purchasing power as a result of the improvement is not as great as it might seem, and for various reasons.

Some of the displaced workers will spend funds that they have set aside for a rainy day, funds which would not have been used immediately. Others will perhaps buy on credit, thus having purchasing power put into their hands even though they are unemployed. Moreover, the tendency of producers to carry on production in advance of the actual sale of the goods will result in purchasing power being placed in the hands of their employees—in the hands of many of the displaced workers who have been taken oneven before the goods on which they are working are marketed.

For reasons such as these the gain in the purchasing power of the retained employees is not offset by the loss in purchasing power of the displaced workers. The latter do, ultimately, get back into employment, even though, it must be confessed, the process of re-absorption seems at the present time to be incompletely understood.

If they did not, if technological progress resulted in permanent unemployment, we would expect that the last century would have furnished us with convincing proof of the fact. But such proof does not exist. While the statistics relating to the amount of unemployment in this country in recent years are not satisfactory, neither on the basis of those we have, nor on the basis of sound deductive reasoning is it possible to maintain that machinery is more and more causing an actual short- age of jobs.

But, someone may object, we are now in a New Era, an Era in which the tempo of technological change has increased, and the old type of reasoning is no longer valid. As Mr. Parrish has moderately stated, "It (referring to the machine) has made invalid every social, political and economic postulate now in use." And again, "Technocracy tells us that we have reached the end of an era." After our experience with the "New Era" leading up to the Fall of 1929, it would be the better part of wisdom to take much of the talk about a new era cum grano salis.

Undoubtedly there has been an increase in the rate of technological change at times during recent years. But there is no reason for expecting that the relative rate is going to keep on increasing constantly and steadily. While the growth of that part of our material culture which has to do with mechanical inventions is cumulative in nature, at times the rate of growth slows down; at other times it spurts ahead. It seems to me, therefore, that it is correct, and helpful, to visualize the situation as a race between "A," representing technological change and labor displacement, on the one hand, and "B," representing labor re-absorption, on the other. "A" is always ahead of "B," but the rate at which each travels varies from time to time, with the result that the distance between them varies, but "B" never catches up to "A." In other words, workers who are displaced through the introduction of machinery are not immediately re-absorbed into industry.

At the present time we likely have a large amount of technological unemployment, but how large, one is not able to say. It would be a very serious error, however, to maintain that the present depression was caused by the phenomenal technological changes made in the twenties. We would have had a depression about this time even if there had been few or no important inventions made during this period, but the present depression is more than an ordinary cyclical slump. Its seriousness has been intensified by various factors, and one of these has been the rapid rate of technological change in the years since the War.

Finally, one should add that in so far as machinery has made possible an economic order in which there are hundreds and thousands of individual producers, each producing largely in anticipation of demand and in ignorance of the exact quantities, and kinds, of goods his competitors are producing, a system in which price is the principal guide of production, that machinery is partly responsible for cyclical as well as for technological unemployment.

V INVENTION," said Veblen, "is the mother of necessity." This tends to be true in the field of private industry; but not to the same extent in the broader field of social life. Inventions have been temporarily displacing thousands of workers, yet we have done little to expedite their reabsorption into industry, or to provide for those of their number who have been in need during the period of enforced idleness. It is obvious that those who have been forced out of jobs through technological changes have been victimized by changes from which society benefits. Society, therefore, has an obligation resting upon it to relieve their distress and assist them in getting back into employment.

Anyone advocating measures directed towards these ends must of necessity quote the statement that John Stuart Mill made in his Principles, that "There cannot be a more legitimate object of the legislator's care than the interests of those who are thus sacrificed to the gains of their fellow citizens and of posterity." But legislators, as well as many of their constituents, seem to care little, and the process of convincing them is a slow one. Partly for this reason, suitable alterations in our thinking and acting to changing material conditions are not made with sufficient rapidity. Or, more accurately, though perhaps less intelligibly, changes in our adaptive nonmaterial culture lag behind changes in our material culture. This was strikingly brought out in the case of industrial accidents, and again is being brought out, vividly and painfully, in the case of technological \unemployment. In time we shall likely deal with such unemployment in a tolerably satisfactory manner, just as we finally adopted workmen's compensation laws, but in the meantime there will be a great deal of human suffering and of economic loss.

But what, specifically, should we strive for? For one thing, an adequate system of unemployment insurance. It should be borne in mind, however, that a system of unemployment insurance, if adopted immediately, would not help much in the present depression. But now is the time to start thinking about, and making plans for, the next one. The conditions are now ripe for the transformation of a worthy idea into legislative measures. During the coming years we shall have a large amount of technological unemployment, and some time in the forties we shall likely find ourselves in a business slump, a cyclical depression, somewhat similar to the one we are now in. A system of unemployment insurance should be set up so that in the halcyon days ahead reserves can be accumulated. Such insurance will not work miracles, but nevertheless "'t is a consummation devoutly to be wished."

We should also make better provision for re-training individuals who have been displaced by machines. We should give them an opportunity of learning a new trade or profession. Moreover, our whole system of vocational training should be greatly extended.

Again, steps should be taken to "humanize" industry. It would be disastrous to try to do this by going back to the crude productive methods used in the many golden ages of the past. It would be foolish for us to declare an "Inventors' Holiday." That smacks too much of the drastic measures adopted by the Erewhonians.

But if we could reduce still more the physical risks of industry; if we could give every individual the "right" to work; and if we could give the workers some voice in the control of industry, we would have done much in the way of humanizing it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleTHE YOUNG MAN IN POLITICS

March 1933 By George H. Moses '90 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

March 1933 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

March 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell