We Are Old Enough

Dear Sir:

The purpose of this letter is to open discussion on the question, what should be the basis for the editorial policy of the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE? This is not to be interpreted as an effort to criticise what has been done in the past, but rather an attempt, based on the assumption that the MAGAZINE will strengthen its financial position with time, to look toward the future. Whatever the editorial policy may be, it should be a, conscious one, approved of not only by the editors, but by the subscribers as well.

One feels that the time is propitious to raise such a question, for during the past year or so the MAGAZINE has given definite signs of coming of age; its appearance has improved markedly, and its contents, especially in a number of notable instances, have exhibited more and more of what one might call maturity. Nevertheless, by and large the MAGAZINE is local in its point of view and significance, for the bulk of its contents deals strictly and narrowly with Dartmouth College and Dartmouth Men. That an alumni magazine would not include such material is somewhat inconceivable, but its continued, highly successful presentation, as in the past, gives rise to a situation that is at once a blessing and an evil. The use of the word evil is hardly meant to imply that the emotions associated with reading about old friends and old places are bad; what is meant is that a more or less exclusive presentation of the social and sentimental by the ALUMNI MAGAZINE must create in the minds of its readers the idea that this is the sole possible function of such a periodical. It is my opinion that this is not so, and, with some sort of an appreciation of the difficulties involved in making such a suggestion a reality, I propose that the MAGAZINE should also be the means by which the College keeps the alumni in contact with the progress of knowledge.

The phrase, progress of knowledge, is to be interpreted broadly, including all fields. I have purposely stated the progress of knowledge, for I feel that nothing could be more deadly than a journal dedicated to rehashing what has been knownan encyclopedia published as a periodical. Furthermore, the progress of knowledge should not be confused with the esoteric or those subjects commonly referred to as arty. At the risk of being pedantic the suggestion is offered that too many persons major in English at college because they believe that in some way or other the study of literature is the key to culture. The type of editorial policy I have in mind would consciously deny such an attitude. It would realize that we are particularly fortunate to be living during one of the most exciting periods in the history of civilization, when changes, many and basic, give our days something of the flavor of the Renaissance. The economic, political, and social changes need no special commendation, and it is obvious to all that they imply definite additions and modifications to what we may call their academic syntheses. What is not so well known, however, is that the laboratory sciences have not only made a multitude of discoveries, but have rebuilt their philosophical foundations as well. The physicist of today regards his science and the world in quite a different light from the physicist of 50 years ago. Such a change must have far-reaching effects in a civilization whose physical structure is dictated by technology.

But rapid and important as the progress of knowledge may be, few of us have at our disposal the time or means to follow it. Our newspapers, tuned to the interests of an hypothetical reader, give but a superficial picture, and our magazines and reviews are generally specialized in their contents. Any publication which attempted to follow the march of our times from the point of view discussed would perform a very real service.

Obviously, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE cannot undertake suddenly to fulfil such a program, if for no other reason than that it lacks the money to buy paper and articles. Nevertheless, to work toward such a goal is not an impossibility, requiring no more than sympathetic interest on the part of both editors and readers. Some such plan as the following might conceivably be used as a beginning. A number of men would volunteer their services, each to act as an editor in some particular field. Each of these men would guarantee the editor-in-chief one appropriate article during the course of the year. Who wrote such an article or by what means it was obtained would not be the business of the editorin-chief; his only concern would be that its length was suitable, its language understandable, and its field-editor responsible for its accuracy. As compensation the writer might receive 50 reprints of his article. At the end of the year the subscribers to the MAGAZINE would be sounded in order to ascertain whether the plan should be continued, modified, or abandoned. If some such start could be made successfully, in time it might be possible to cooperate with other alumni magazines, such articles (and possibly advertising) being obtained by the group, but being published independently though simultaneously.

August 31, 1933.28 Mellen Street,Cambridge, Mass.

Ignorance in the North

Dear Sir:

Will you accept from a Dartmouth alumnus who is Southern-born and Southern-bred but who received his educationhigh school, college and law—in the East and who after the lapse of more than thirty years tries to maintain some of those principles of fairness and humanity imbibed during four years at Dartmouth, an expression of opinion concerning certain recent events that have brought the State of Alabama and its people into unfavorable prominence in the eyes of the nation at large? I refer, of course, to the so-called "Scotsboro Cases" and the more recent episode at Tuscaloosa, which reached its climax yesterday in the lynching of three negroes.

The people of the South—what they stand for in general and their attitude towards the negro—must first be understood. This is necessary for the people of the other sections of the country are far more ignorant of the South and its people than we of the same degree of culture and education are of the other sections. This is not a criticism of the people of other sections. It is perfectly natural that this condition should exist. People from the other sections seldom visit us except on matters of business, while great numbers of our people spend their vacations in other sections. The direct consequence of this is that you know about us only from hearsay, while we know about you from personal observation. As examples of what I am saying I will mention two incidents that occurred while my wife and I were in Hanover some years ago at a class reunion. One of the ladies asked my wife if she knew what a hot-air furnace was, and another remarked to her when they had climbed a hill of moderate height, that, not being used to climbing hills, it must have been an exhausting experience for her. Both were tremendously surprised to learn that we seldom had a winter without the temperature going down to somewhere close to zero and that in the immediate vicinity of Birmingham we have higher and steeper nills than are found in the immediate vicinity of Hanover.

We know of that ignorance of us and of the tendency to group us all into one class and our people resent it. We have forgotten the Civil War most of the time and when we do think of it, we are glad that Secession was not successful and the only feeling we have against any other section is caused by the realization that we are regarded as a sort of semi-civilized race living in a land covered with swamps and teeming with dangerous beasts. We do resent that. We are pretty much like everybody else. We are good, bad and indifferent: we are kind and merciful—cruel and vindictive—generous and grasping—cultured and boorish—educated and ignorant. In fact, we have every type from the highest to the lowest, just as every other section has.

Now how do we treat the negro? Just exactly as the poor and ignorant are treated in every part of the world. Our better classes and those of us who believe in fairness and mercy are the best friends that the negro ever had or ever will have anywhere. We know. them; appreciate their good qualities; excuse their weaknesses and try to help them. The avaricious exploit them; the cruel oppress them and the narrow-minded and ignorant abuse them. The average negro does not get justly treated but neither are the poor and ignorant justly treated anywhere. If the average negro is not properly represented in Court it is because he hasn't the money to employ the best of counsel. If he can furnish the fee he can get the best of our attorneys to defend him and they will fight as hard for him as for any white client. What I am trying to state is that except in one sense our negroes get the same treatment that whites of the same degree get in other sections.

One thing that we insist on and mean to continue to insist on is social separation of the races. We have no idea of having this part of our land inhabited by a negroid race. If that be wrong, we are wrong, but we are so convinced that we are right that no argument would change us and if you accept us into your friendship you must do so realizing that we are fixed in that idea. You admit negroes to your schools, public and private; we spend thousands and thousands of dollars every year over and above what is paid by negroes as taxes, to provide separate schools for them. This is but one example of the length to which we are willing to go to preserve the status quo.

Now what about the recent matters that have attracted so much attention? Even a casual reading of the Supreme Court report of the "Scotsboro Cases" will show that it did not pass upon the guilt or innocence of the accused. It merely decided that a requirement of law had not been complied with. If you will read the reports of these cases in the Alabama Reports you will find a good deal said in regard to the testimony. These men are still to be tried so it would be very improper at this time to express an opinion as to their guilt or innocence.

The Tuscaloosa case is a horse of an entirely different color. These men had never been tried, and, if what a well-known citizen of that city told me about ten days ago is true, the chances are that they never would have been convicted. The killing of these negroes is resented by the law-abiding citizens of this State just as much as it is by anyone anywhere. You have your gangs and hoodlums everywhere—so do we and this act no more represents the attitude of the people of the South than the famous "St. Valentine's Day Massacre" represents the attitude of the people of Chicago. A lawless gang committed one act—another lawless gang committed the other. One thing more and I am done, but that is probably the only important thing in this entire article. Without exception, we all bitterly resent the intermeddling in our affairs by sinisterly inclined outsiders. We don't interfere with the local administrations of justice in other sections of the country, and we feel that we should be left alone to administer our matters of this kind.

Those of us who represent the better elements will always stay within the law no matter what happens but, if this intermeddling is persisted in, those of us who are not so "law-minded" will let their resentment get the better of them and there is no telling what will happen. This is not written as a threat but as a plea for the negro who will be the chief sufferer. Those Tuscaloosa negroes would be alive and well today, but for the interference of those I.L.D. lawyers from New York. If they are sincere in their desire to help the negro let them stay at home. If they wish to furnish money with which to hire competent counsel, no one can object to that, but let that counsel be local men who enjoy the respect of the community. Help might be given in that way but the present course of procedure has nothing in it but harm for the negro and as one who likes him and sympathizes with him I would deeply regret such consequences.

August 15, 1933Jackson BuildingBirmingham, Ala.

Sigma Chi's New Home

The New Beta House

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

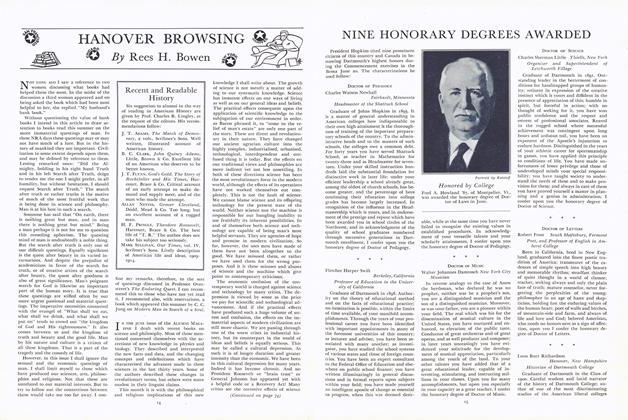

Article

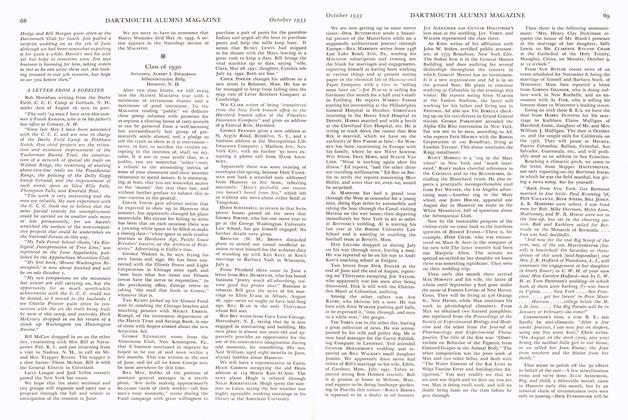

ArticleNEW COLLEGE RESPONSIBILITIES

October 1933 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

October 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

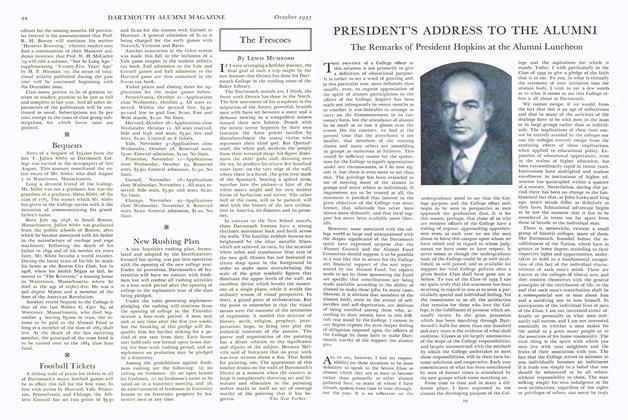

ArticlePRESIDENT'S ADDRESS TO THE ALUMNI

October 1933 -

Article

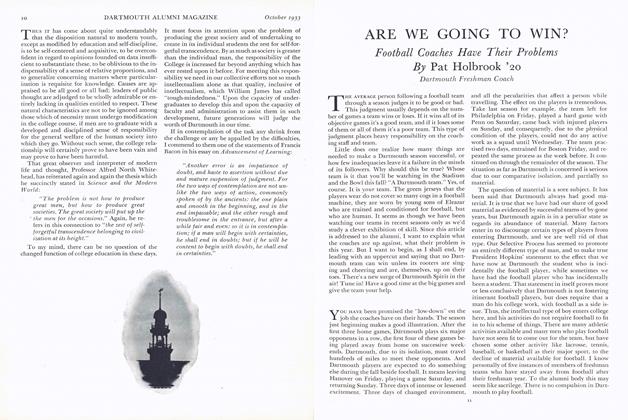

ArticleARE WE GOING TO WIN?

October 1933 By Pat Holbrook '20 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

October 1933 By Harold P. Hinman