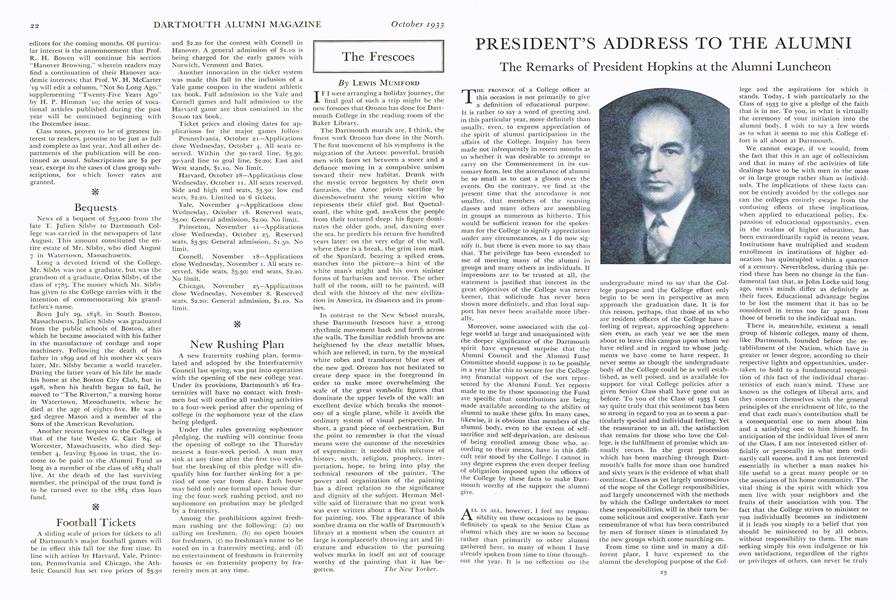

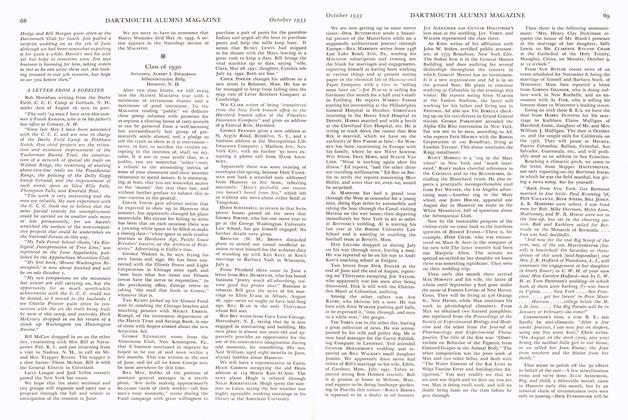

IF I were arranging a holiday journey, the final goal of such a trip might be the new frescoes that Orozco has done for Dartmouth College in the reading room of the Baker Library.

The Dartmouth murals are, I think, the finest work Orozco has done in the North. The first movement of his symphony is the migration of the Aztecs: powerful, brutish men with faces set between a sneer and a defiance moving in a compulsive unison toward their new habitat. Drunk with the mystic terror begotten by their own fantasies, the Aztec priests sacrifice by disembowelment the young victim who represents their chief god. But Quetzalcoatl, the white god, awakens the people from their tortured sleep: his figure dominates the older gods, and, dawning over the sea, he predicts his return five hundred years later: on the very edge of the wall, where there is a break, the grim iron mask of the Spaniard, bearing a spiked cross, marches into the picture—a hint of the white man's might and his own sinister forms of barbarism and terror. The other half of the room, still to be painted, will deal with the history of the new civilization in America, its disasters and its promises.

In contrast to the New School murals, these Dartmouth frescoes have a strong rhythmic movement back and forth across the walls. The familiar reddish browns are heightened by the clear metallic blues, which are relieved, in turn, by the mystical white robes and translucent blue eyes of the new god. Orozco has not hesitated to create deep space in the foreground in order to make more overwhelming the scale of the great symbolic figures that dominate the upper levels of the wall: an excellent device which breaks the monotony of a single plane, while it avoids the ordinary system of visual perspective. In short, a grand piece of orchestration. But the point to remember is that the visual means were the outcome of the necessities of expression: it needed this mixture of history, myth, religion, prophecy, interpretation, hope, to bring into play the technical resources of the painter. The power and organization of the painting has a direct relation to the significance and dignity of the subject. Herman Melville said of literature that no great work was ever written about a flea. That holds for painting, too. The appearance of this sombre drama on the walls of Dartmouth's library at a moment when the country at large is complacently throwing art and literature and education to the pursuing wolves marks in itself an act of courage worthy of the painting that it has begotten.

The New Yorker.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Article

ArticleNEW COLLEGE RESPONSIBILITIES

October 1933 By Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

October 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT'S ADDRESS TO THE ALUMNI

October 1933 -

Article

ArticleARE WE GOING TO WIN?

October 1933 By Pat Holbrook '20 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

October 1933 By Harold P. Hinman

Article

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER CURLING CLUB PUTS STUFF ON ICE

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleThe Figures Grow

January 1958 -

Article

ArticleNewsletter Editor of the Year

JUNE 1970 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleSearching for Veritas

December 1976 By BRAD W. BRINEGAR '77 -

Article

ArticleTHE NAUTICAL LIFE

June 1944 By PROF. RICHARD H. GODDARD '20