Every now and then, wandering from the beaten path, we run into some unsuspected nook in the new Dartmouth. In Carpenter Hall the other afternoon we went around a corner and up some steps and found a studio, where undergraduate artists, dilettantes, and daubers mayfinda sanctum forself-expression, with appropriate equipment. And it seems that there will be occasional visiting artists who will give instruction to those who happen to be around listening. (At least, that is to say, it would be nice and bohemian and careless like that if we were running it). Charles H. Woodbury, the Boston artist, was in Hanover recently for this purpose. He gave private criticisms, conducted group exercises in drawing—in which he used moving picturesand discussed problems in the appreciation of etching and water-color in connection with the exhibition of his pictures in the galleries.

One day, feeling like a walking questionnaire, we stormed in on a workman who was touching up the wall paper in the Sanborn Room in Sanborn House. Now this was no ordinary wall paper, and no ordinary workman. It isn't even an ordinary room, having an irregular floor "of a certain age" and very old windows with very old shutters. The workman had been sent from a New York "studio," and the wall paper came either from France or some old homestead in Virginia and was two or three hundred years or so old. The details are a little vague. What really impressed us was the number of months and the number of men which were required to make the wall paper, as the touching-up artist described the process while mixing paint with the yolks of eggs for his work. It seems that this landscape paper was printed in small sections from blocks of wood, and that each darker shade was obtained by an additional impression. It is the sort of thing which could only be done with cheap labor, way back when. We gasped goopishly while hearing what the paper, for which there is a present vogue, probably cost. We would tell the world that this man's college is no longer a backwoods piker.

There is a cozy little library for honors men upstairs in Sanborn House which, it is rumored, will be open all hours of the night, a sanctum of lucubrations, the midnight-oil burner's heaven. This, however, is only a rumor.

There are so many cozy little libraries around. The Tower Room belongs in the category of the perfect. The art library in Carpenter Hall somehow contrives to be both stately and comfortable, luxurious and sedate. Every now and then this Undergraduate Chair-sitter-in drops in there, picks up a random book, and sinks in one of those good chairs, to turn pages—just as any child looks at any picture book. And the Sanborn House library—not open yet—with its rich paneling, is really too beautiful for us undergraduate hoi polloi. If we don't get on sociable, comfortable terms with books, something is wrong.

By way of contrast, we have a dim, sophomoric memory of the medical library, in that bleak white building on the side of the hill, reminiscent of Hanover's middle ages. One reaches the library by climbing a flight of narrow wooden steps—the sort, you know, one would climb expecting to find a hall full of gas jets with Dr. Dobbs, Painless Dentist, on the left and Mademoiselle Mullins, Modiste, on the right. It sort of seems that there were gas jets in this stairway. Anyway, the library, when you reach it, is just like any Elks Club library, without the cigar smoke.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1930 By Truman T. Metzel -

Article

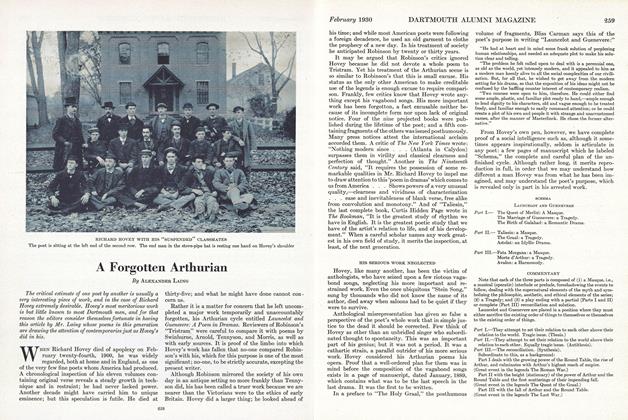

ArticleA Forgotten Arthurian

February 1930 By Alexander Laing -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1930 -

Sports

SportsThe Dartmouth 1929 Football Team

February 1930 By Alton K. Masters, '30 -

Article

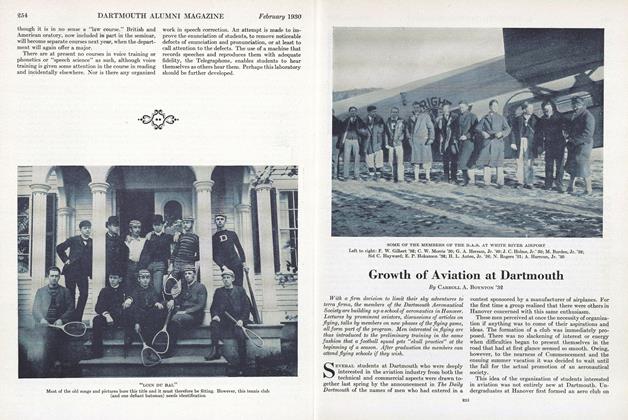

ArticleGrowth of Aviation at Dartmouth

February 1930 By Carroll A. Boynton '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

February 1930 By Frederick W. Andres

Albert I. Dickerson

-

Article

ArticleOne Night Stands

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

DECEMBER 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

OCTOBER 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

February 1936 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1937 By Albert I. Dickerson