Thayer School, 1903, Executive Vice-President and Director,Turner Construction Co., New York City

ANY ATTEMPT TO appraise the value of a vocation is beset by difficulties. There are no standards for appraisers and there are no criteria of values. Experience shows that one is apt to favor the things with which he is familiar and to dislike or at least to look with suspicion upon the unfamiliar. Bias creeps in notwithstanding every conscientious effort and every desire to exclude it, and conceptions of value are the results of personal experience. Who is there qualified to make a comparison between vocations, inasmuch as experience and proficiency in any given line precludes similar familiarity and experience in other lines, and a jack-of-all-trades is probably not equipped to give valuable help in any one? Again, standards of value vary. What with one individual will be regarded as a desirable asset, to be sought after and safeguarded, with another will be unappreciated and ignored. There is no universal medium of exchange with which to make comparisons.

The best that can be hoped for is that the experience of one individual expressed in general philosophic terms with his standards of value clearly understood and appreciated, may be of service to some other individual wavering in the choice of a life work or just starting actively in the practice of some profession.

Starting then with the premise that comparisons with other professions cannot properly be made, at least not by an engineer, what are the advantages that can be hoped for in the selection and rigorous following of engineering as a vocation? What are its rewards, its drawbacks; what is its total appraised value?

THERE ARE THOSE, of course, who will insist that after all the only rational standard of value is the dollar. That to maintain existence, things must be had and things can only be had by obtaining in exchange for service, a sufficient number of hard dollars. There is so much merit in this contention that argument to the contrary is quite futile. Under our present system, dollars are a necessity. But there are other considerations which in the last analysis are of so much more weight in the opinion of many that the income producing value of a profession in dollars can be given secondary importance. In ap- praising the value of engineering as a vocation, therefore, we will deliberately leave out of consideration the actual production of monetary income and will devote our efforts to pointing out those advantages which may be expressed in terms of greater interests, more complete satisfactions, deeper insights and wider horizons, which after all are assets of a much more lasting character.

Engineering, doubtless, does not appeal to all types of minds. An engineer has been defined as one who utilizes the forces of nature for the benefit of humanity. But a true engineer must be much more than that. He must be in reality one who has a compelling desire to get at the bottom of things or at least to dig as far down as his tools will permit; one who has an inborn curiosity to know why things happen and if the things that happen are detrimental, to find preventives. Engineering and the kindred scientific vocations appeal particularly to those individuals who, as children, could not resist the temptation of taking a watch apart to see what made it go and who made the lives of their parents miserable with questions as to the workings and origins of things, and were never satisfied with the answers. To one who is satisfied to accept things as he finds them and is not curious enough to scratch below the surface, engineering can offer very little and he would better find a vocation more suited to his temperament. No vocation can prove satisfactory if it becomes at any time distasteful. Nothing could be more tragic than the remark of a man who, having spent practically all of his life in one profession, summed up all his experience in the four words, "I never liked it."

Given, then, individuals who by. temperament are curious to understand as far as possible the phenomena and the processes of the physical world, who have the ability to think logically, who are not afraid of hard work either mental or physical, and who are persistent in reaching out for and attaining goals; to such, engineering has much to offer.

FIRST OF ALL the study of engineering and its allied scientific principles, together with the experience gained from active practice, provides answers to insistent questions. It opens doors upon wide unsuspected vistas and presents subjects for interesting investigation and speculation probaby unsurpassed in any other profession, and answers many questions in any line of work which a man trained as an engineer might later pursue. A bridge to an individual with engineering or scientific training, although he is not a professional bridge builder, is not merely a highway convenience accepted without thought or interest, but rather a unified combination of members and connections each with a purpose and each proportioned for the work it has to do. To the layman a bridge may be merely esthetic in its form and general composition, but to the engineer it is a thing of beauty because of his inner appreciation of how loads have been transferred by means of materials under stress, the question of why and how it does its work being satisfactorily answered.

Drawing a glass o£ water from the faucet in a bathroom may be accepted without question or further thought, or it may call up a long train of associated ideas beginning with fixtures, faucet pressures and piping, and ending with rainfall, reforestation and stream flow. To one, interest begins and ends with the glass of water. To another, interest persists through an intricate combination of operations, devices and natural phenomena all unified in an organized pattern. The White and Green Mountains with their forests, streams, lakes and sunsets provide interest for all those who have an eye for the beauty of the outdoors, but to the engineer or the scientist, there is added the interest which results from the knowledge, even superficial, of geologic history, glaciers, terminal moraines, pre-Cambrian layers, igneous outcrops, table land erosions, and sedimentary deposits. To the engineer, mountains take on new meaning and artesian wells become not only sources of water but sources of absorbing interest. The understanding, even in principle, of the natural phenomena involved in these things provides a store of interest which once gained is like the handful of meal in the barrel and the widow's cruise. As a means whereby insight is gained as to the meaning of every-day occurrences, the study and practice of engineering principles are of unequaled value.

Again, engineering belongs to a group of activities which are distinctly creative, involving the interesting process of transforming ideas into realities. It is the function of the engineer to materialize an idea to meet a need. A new bridge or a new water supply starts with a nebulous and indefinite notion which gradually takes shape as a mental picture. This picture given permanent character in plans and specifications is finally materialized as a reality in the completed project. The satisfaction of seeing a mental picture emerge as the completed material project with smooth working functions, meeting some definite need, is a reward quite independent of the fee or commission received or the public recognition of the engineering skill involved.

FROM THE DAWN of history human beings have been continuous in their efforts to harness, control and use natural forces. After the ravages of a flood or a hurricane, we sometimes wonder how well they have succeeded and whether the harness is holding. Nevertheless the fact remains that the attempt is ever being made with at least partial success and the effort will go on as long as man is the thinking animal that at present he is. Streams are successfully impounded for water supply, fuel extracted from the earth lights our cities, transports us from place to place and turns the wheels of industry. Not satisfied with remaining on the earth, we are navigating the sea and the air. To be sure the Cyclops with its cargo of coal and men disappears without a trace, the Akron crashes in a tangled mass of wreckage, and the Yellow River changes its course after 400 years, all without man being able to make more than a slight gesture of control. But the process of harnessing goes on and will go on as long as engineers and scientists are impelled by a spirit of adventure to peer further into the unknown and to attempt the seemingly impossible. Not least among the advantages of the engineering profession is the furnishing of an outlet for that same spirit of adventure which is, more nearly than anything else, the fountain of eternal youth.

To be sure, there are disadvantages. The training is long, and if thorough, sometimes gruelling. Mathematical proficiency is not acquired over night and mathematical proficiency implies more than the ability to juggle formulae and use meaningless abstractions. Real proficiency implies an understanding and a visualization of the relationships involved in mathematical expressions and the ability to see through the symbols to the things which they represent. There is plenty of hard work to be done and results are a function of time as well as effort. Insight into fundamental principles is not gained by superficial contact. Physical hardship is not unknown and there are phases when overalls and rubber boots become a habit and mud and water are close companions. There are times when hours are long and emoluments small; when the slide rule and the logarithm table become burdens, and all vision and perspective are obscured by a cloud of wearisome computations; when organizations, systems, routines and processes seem to be more important than the product for which they are designed.

THE PROFESSION OF engineering is one in which routine and monotony usually play little part. To be sure, there are some mathematical computations which are tedious and fatiguing, but on the whole the problems are ever changing. No two buildings are just alike; no two water supply systems present the same problems; no two railroads have the same difficulties in track maintenance and fuel supply. The basic principles involved are the same but the application is different in each individual case requiring intensive study, resourcefulness and ingenuity. Standards are employed and are useful as a record of past experience, so that in solving problems past experience is always available, but each new problem presents a new phase which must be met by new devices and new methods. Engineers can, of course, became habit ridden and hide bound like other individuals but the incentive is to keep the mind alert and on the lookout for new solutions to old problems.

But all these things are transient. There comes a day when the fog lifts and a lot of hitherto undiscovered territory suddenly comes into view and the significance of it all rushes at one, accompanied by a surge of feeling unexperienced before; that is, if one has succeeded in remaining a person rather than becoming a machine.

One of the tragedies of the present economic disturbance is that so many men, when they become bankrupt financially, are bankrupt completely inasmuch as they have acquired no valuable assets which survive the washing away of the storehouse of material things. Engineering, and the same is true of the allied sciences, if pursued as a calling rather than as a job and if used so that personality is not submerged but allowed to emerge and grow, furnishes a source of assets in the form of interests, satisfactions, and accomplishments, which survive the destruction of more material things.

"Engineering Transforms Ideas into Realities"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

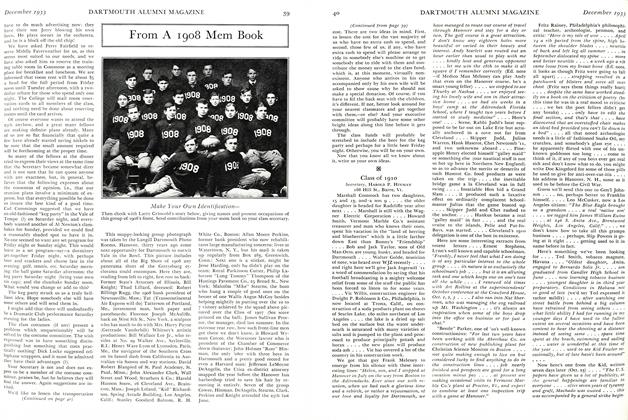

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1933 By F. William Andres, Gus Wiedenmayer -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

December 1933 By S. C. H.

Article

-

Article

ArticleBEFORE CHAPEL ON A SPRING MORNING

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE CREDIT TO BE GIVEN FOR EUROPEAN STUDY TOUR

April, 1922 -

Article

ArticleCommencement and Reunion Programs

June 1950 -

Article

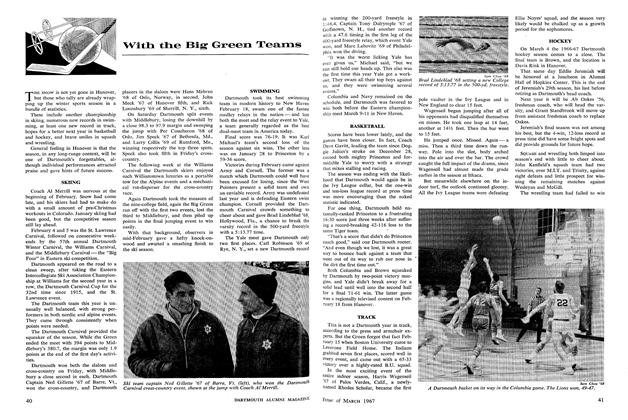

ArticleSWIMMING

MARCH 1967 By DAVE MARTIN '54 -

Article

ArticleGREEN JOTTINGS

OCTOBER 1972 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

Article"Janssen Plan for Peace"

OCTOBER 1958 By JOHN HURD '21